Prescott National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona

Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D DEC 10 1956 Water Resources of Bill Williams River Valley Near Alamo, Arizona By H. N. WOLCOTT, H. E. SKIBITZKE, and L. C. HALPENNY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1360-D An investigation of the availability of water in the area of the Artillery Mountains manganese deposits UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract....................................................................................................................................... 291 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 292 Purpose.................................................................................................................................... 292 Location................................................................................................................................... 292 Climatological data............................................................................................................... 292 History of development........................................................................................................ -

Geologic Map of the Chino Valley North 7½' Quadrangle, Yavapai County, Arizona

DIGITAL GEOLOGIC MAP DGM-80 Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CHINO VALLEY NORTH 7½’ QUADRANGLE, YAVAPAI COUNTY, ARIZONA, V. 1.0 Brian. F. Gootee, Charles A. Ferguson, Jon E. Spencer and Joseph P. Cook December 2010 ARIZONA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geologic Map of the Chino Valley North 7½' Quadrangle, Yavapai County, Arizona by Brian F. Gootee, Charles A. Ferguson, Jon E. Spencer, and Joe P. Cook Arizona Geological Survey Digital Geologic Map DGM-80 version 1.0 December, 2010 Scale 1:24,000 (1 sheet, with text) Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 This geologic map was funded in part by the USGS National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, award no. 08HQAG0093. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents Table of Contents......................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Geologic Discussion ................................................................................................................... 3 Quaternary faulting ...........................................................................................................3 -

Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998

GILA TOPMINNOW, Poeciliopsis occidentalis occidentalis, REVISED RECOVERY PLAN (Original Approval: March 15, 1984) Prepared by David A. Weedman Arizona Game and Fish Department Phoenix, Arizona for Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico December 1998 Approved: Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions required to recover and protect the species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) prepares the plans, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State and Federal Agencies, and others. Objectives are attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Time and costs provided for individual tasks are estimates only, and not to be taken as actual or budgeted expenditures. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor official positions or approval of any persons or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. ii Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Original preparation of the revised Gila topminnow Recovery Plan (1994) was done by Francisco J. Abarca 1, Brian E. Bagley, Dean A. Hendrickson 1 and Jeffrey R. Simms 1. That document was modified to this current version and the work conducted by those individuals is greatly appreciated and now acknowledged. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

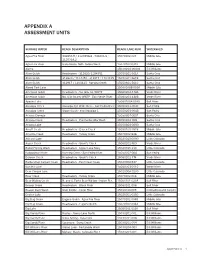

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Annual Reportarizona YEARS 40…Of Conserving Land and Water to Benefit People and Nature

2006 annual reportArizona YEARS 40…of conserving land and water to benefit people and nature In 1966 a group of conservation-minded citizens raised money to buy the Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, and The Nature Conservancy in Arizona was born. Over the years that followed, nature preserves throughout the state were purchased by or donated to the Conservancy. They had a common focus: protecting water and VISION: We will ensure freshwater sources are restoring the health of the land. secure and sustainable in order to support our growing population and the rich diversity of life This 40th annual report documents the natural evolution of an that depends on fresh water to thrive. We will work organization whose mission calls upon us to preserve the diversity with water users, providers and those who depend on growth to create the incentives and limits that of life on Earth. We have come to cherish Arizona’s rich biological will guide future growth and create well-planned heritage. We have learned about our vital connections with communities in the face of uncertainty created by neighboring states and other countries through a system of similar securing our future global climate change. habitats or ecoregions. We are beginning to understand how special places are vulnerable to changes that occur many miles away. And, we water now know that change can be friend and foe. Today we are working at an unprecedented scale, on critical issues not recognized 40 years ago, such as Upper San Pedro Partnership Verde River Greenway With the added urgency of the first recorded no- The Conservancy sponsored field trips and provided global warming and the decline in forest health. -

The Colorado River: Lifeline Of

4 The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest Clarence A. Carlson Department of Fishery and Wildlife Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 Robert T. Muth Larval Fish Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA 80523 1 Carlson, C. A., and R. T. Muth. 1986. The Colorado River: lifeline of the American Southwest. Can. J. Fish. Aguat. Sci. In less than a century, the wild Colorado River has been drastically and irreversibly transformed into a tamed, man-made system of regulated segments dominated by non-native organisms. The pristine Colorado was characterized by widely fluctuating flows and physico-chemical extremes and harbored unique assemblages of indigenous flora and fauna. Closure of Hoover Dam in 1935 marked the end of the free-flowing river. The Colorado River System has since become one of the most altered and intensively controlled in the United States. Many main-stem and tributary dams, water diversions, and channelized river sections now exist in the basin. Despite having one of - the most arid drainages in the world, the present-day Colorado River supplies more water for consumptive use than any river in the United States. Physical modification of streams and introduction of non-native species have adversely impacted the Colorado's native biota. This paper treats the Colorado River holistically as an ecosystem and summarizes current knowledge on its ecology and management. "In a little over two generations, the wild Colorado has been harnessed by a series of dams strung like beads on a thread from the Gulf of California to the mountains of Wyoming. -

(Central Arizona) GEOSPHERE

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Incision history of the Verde Valley region and implications for uplift of the Colorado Plateau (central Arizona) 1 2 2 GEOSPHERE; v. 14, no. 4 Richard F. Ott , Kelin X. Whipple , and Matthijs van Soest 1Department of Earth Sciences, ETH Zurich, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland 2School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, 781 S. Terrace Road, Tempe, Arizona 85287, USA https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01640.1 12 figures; 3 tables; 1 supplemental file ABSTRACT et al., 2008; Moucha et al., 2009; Huntington et al., 2010; Liu and Gurnis, 2010; Flowers and Farley, 2012; Crow et al., 2014; Darling and Whipple, 2015; Karl- CORRESPONDENCE: richard .ott1900@ gmail .com The record of Tertiary landscape evolution preserved in Arizona’s transition strom et al., 2017). As part of this debate, the incision of the Mogollon Rim, zone presents an independent opportunity to constrain the timing of Colo the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau (Fig. 1), is not well constrained CITATION: Ott, R.F., Whipple, K.X., and van Soest, rado Plateau uplift and incision. We study this record of landscape evolution in the literature, and disparate ideas about its formation and incision history M., Incision history of the Verde Valley region and implications for uplift of the Colorado Plateau by mapping Tertiary sediments, volcanic deposits, and the erosional uncon have been proposed (Peirce et al., 1979; Lindberg, 1986; Elston and Young, ( central Ari zona): Geosphere, v. 14, no. 4, p. 1690– formity at their base, 40Ar/39Ar dating of basaltic lava flows in key locations, and 1991; Holm, 2001). -

Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona

Analysis of sediment dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona Andrew C. Wilcox and Franklin Dekker Department of Geosciences Center for Riverine Science and Stream Renaturalization University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812-1296 Paul Gremillion (Northern Arizona University) and David Walker (University of Arizona) Collaborators: Patrick Shafroth (USGS), Cliff Riebe (University of Wyoming), Kyle House (USGS), John Stella (State University of New York) Report prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) February 6, 2013 DRAFT FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 Catchment Erosion Rates and Sediment Mixing in a Dammed Dryland River ............................. 11 Dryland River Grain-Size Variation due to Damming, Tributary Confluences, and Valley Confinement ................................................................................................................................. 28 Analysis of Sediment Dynamics in the Bill Williams River, Arizona: Hydroacoustic Surveys and Sediment Coring ............................................................................................................................ 46 Coupled Hydrogeomorphic and Woody-Seedling Responses to Controlled Flood -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River- Salton Sea Area By BURDGE IRELAN WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER SALTON SEA AREA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72 610761 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract . _.._.-_. ._...._ ..._ _-...._ ...._. ._.._... El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction .._____. ..... .._..__-. - ._...-._..__..._ _.-_ ._... 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek .._________________.____.___-._____. _ E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam ____________ 2 Havasu Creek __._____________-...- _ __ -26 Lees Ferry .._._..__.___.______.__________ 4 Virgin River ..__ .-.._..-_ --....-. ._. 26 Grand Canyon ................._____________________..............._... 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam ..........._._..- -_-._-._................-._._._._... 8 Hoover Dam .__-.....-_ .... .-_ . _. 26 Lake Havasu - -_......_....-..-........ .........._............._.... 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead ............-... .-.....-..... 26 Imperial Dam .--. ........_. ...___.-_.___ _.__.__.._-_._.___ _ 12 Bill Williams River ......._.._......__.._....._ _......_._- 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 . -

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography

Supplemental Materials and Information: CRB Geography Study Area Detail The 283,384 km2 Upper Colorado River Basin (UCRB) drains the West Slope of the Rocky Mountains and the stratigraphically largely undeformed Colorado Plateau section of the Rocky Mountains geologic province. Colorado Plateau strata range in age from early Proterozoic (1.84 billion years ago) metamorphic crystalline basement rock, to Precambrian through early Cenozoic sedimentary strata, with late Cenozoic basalts [32], and ranging in elevation from 4352 m down to 350 m on Lake Mead Reservoir. Every natural CRB tributary we have examined thus far arises from springs, springfed wetlands, or small groundwater-fed lakes e.g., [21]. For example, UCRB mainstream flow arises from two primary sources [12,13]. The 1112 km-long Green River sources at an unnamed springfed fen 2 km southwest of Mt. Wilson in the Wind River Range in Sublette County, Wyoming, and also receives surface snowmelt water from Minor Glacier and other snowfields near Gannet Peak (4087 m). Along its course, the Green River receives flow from the Yampa and White Rivers, and delivers a long-term mean discharge at its mouth of 173 m3/sec. Similarly, the upper Colorado River similarly arises from a springfed fen at La Poudre Pass in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, and receives flow downstream from the Gunnison, Dolores, and other rivers and streams [13]. Downstream from the Green and Colorado Rivers confluence in Canyonlands National Park, Utah the mainstream is joined by the flows of: the Fremont/Muddy, San Juan, and Escalante Rivers in Lake Powell Reservoir, and the Paria River near Lees Ferry, Arizona.