Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

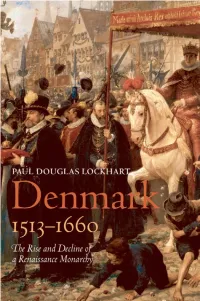

The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy

DENMARK, 1513−1660 This page intentionally left blank Denmark, 1513–1660 The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy PAUL DOUGLAS LOCKHART 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Paul Douglas Lockhart 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lockhart, Paul Douglas, 1963- Denmark, 1513–1660 : the rise and decline of a renaissance state / Paul Douglas Lockhart. -

The Science of Astrology: Schreibkalender, Natural Philosophy, and Everyday Life in the Seventeenth-Century German Lands

The Science of Astrology: Schreibkalender, Natural Philosophy, and Everyday Life in the Seventeenth-Century German Lands A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences by Kelly Marie Smith M.A. University of Cincinnati, December 2003 B.S. Eastern Michigan University, December 2000 Committee Chair: Sigrun Haude, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation explores the use of Schreibkalender, or writing-calendars, and their accompanying prognostica astrologica to evaluate how ideas about seventeenth-century natural philosophy – particularly the relationship between astronomy and astrology – changed throughout the period. These calendars contain a wealth of information that demonstrates the thirst early modern readers had for knowledge of the world around them. Because Schreibkalender and prognostica were written annually for the general populace and incorporated contemporary ideas regarding natural philosophy, they provide a means to assess the roles of both astronomical and astrological ideas during this period and how these changes were conveyed to the average person. Not only did authors present practical information related to the natural world, but they also explained basic philosophical principles and new discoveries to their audience. This research examines how changing ideas about the role of natural philosophy and its direct influence on everyday life developed over the course of the seventeenth century. An examination of the Schreibkalender and prognostica reveals a shift in emphasis throughout the period. Early calendars (approximately 1600-30) presented direct astronomical and astrological information related to the daily life of the average person, whereas those from the middle of the century (~1630-70) added helpful details explaining astronomical and astrological concepts. -

The Nova Stella and Its Observers

Running title: Nova stella 1572 AD The Nova Stella and its Observers P. Ruiz–Lapuente ∗,∗∗ 1. Introduction In 1572, physicists were still living with the concepts of mechanics inherited from Aris- totle and with the classification of the elements from the Greek philosopher. The growing criticism towards the Aristotelian views on the natural world could not turn very produc- tive, because the necessary elements of calculus and the empirical tools to move into a better frame were still lacking. However, in astronomy, observers had witnessed by that time the comet of 1556 and they would witness a new one in 1577. Moreover, since 1543 when De Revolutionibus Orbium Caelestium by Copernicus came to light, the apparent motion of the planets had a radically different explanation from the ortodox geocentrism. The new helio- centric view slowly won supporters among astronomers. The explanations concerning the planetary motions would depart from the “common sense” intuitions that had placed the earth sitting still at the center of the planetary system. Thus the “nova stella” in 1572 happened in the middle of the geocentric–versus–heliocentric debate. The other “nova”, the one that would be observed in 1604 by Kepler, came just shortly after the posthumous publication of Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata1 which contains most of the debates in relation to the appearance of the “new star”2. arXiv:astro-ph/0502399v1 21 Feb 2005 The machinery moving the planetary spheres, i.e. the intrincate system of solid spheres rotating by the motion imparted to them as the wheels in a clock, was not directly affected by the new heliocentric proposal. -

The Academic Genealogy of Swapnil Haria

�� John Mauropus, ���-���� �� Johannes VIII Xiphilinus, ����-���� �� Nicetas Byzantius The Academic University of Constantinople University of Constantinople, ���� | Patriarch of Constantinople �� Michael Psellos, ����-���� University of Constantinople Genealogy of �� John Italus, ����-���� University of Constantinople �� Theodore of Smyrna Swapnil Haria University of Constantinople �� Michael Italikos, c. ���� �� Stephanos Skylitzes Philippolis Trebizond | Constantinople, ���� Academic ancestors include two saints, Copernicus, Erasmus, and Leibniz. This �� Theodoros Prodromos, ����-���� Patriarch school, Constantinople geneology almost certainly contains errors and omissions. Information compiled �� Demetrios Karykes Smyrna, ���� from/by Mathematics Genealogy Project, �� Theodorus Exapterigus �� Nicephorus Blemmydes, ����-���� Neurotree, Nikos Hardavellas, Mark D. Hill, Prusa, Nicea | Smyrna, Scamander | Monastery of Ephesus Timothy Sherwood, and Gio Wiederhold. �� Georgius Acropolitus, ����-���� Nicae �� Georgius Pachymeres, ����-���� Constantinople �� Manual Byrennius, ����-XXXX Constantinople �� Theodore Metochites, ����-���� Nicea �� Elder St. Nicodemus of Vatopedi �� Nicephorus Gregoras, ����-���� �� Manuel Holobolos Vatopedi Monastery, Mt. Athos, ��XX Constantinople Rhetor at the court of Nicae, ���� �� St. Gregory Palamas, ����-���� �� Simon of Constantinople, ����-���� Constantinople | Vatopedi Monastery, Mt. Athos | Thessaloniki Pera near Contantinople �� Nilus Cabasilas, ����-���� �� Philip of Pera (Philippo de Bindo Incontri) -

Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm

Medical History, 1995, 39: 78-94 The Reception of Paracelsianism in early modem Lutheran Denmark: from Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm OLE PETER GRELL* Retrospectively, the appointment in 1571 of the two Paracelsian physicians, Peter Severinus (1540-1602) and Johannes Philip Pratensis (1543-1576), as royal physician to King Frederik II of Denmark-Norway and professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen respectively, can be seen to have marked not only the introduction of Paracelsianism, but also the start of the medical renaissance in Denmark. The importance of Peter Severinus and his work Idea medicina philosophica? (Basle, 1571) in making Paracelsus's ideas acceptable within the scholarly community of early modem Europe was widely recognized by contemporary admirers, as well as antagonists. Since contemporaries labelled Paracelsus the Luther of medicine, it is tempting to widen the analogy and see Severinus as Melanchthon to Paracelsus's Luther. Like Melanchthon, Severinus eased and modified his mentor's ideas, thereby making them acceptable within the political and scholarly world where hitherto they had lacked appeal. Thus, the Heidelberg-based physician and theologian Thomas Erastus recommended Severinus's book as the most palatable face of Paracelsianism as early as 1579,' while another influential critic, the Wittenberg professor of medicine, Daniel Sennert, in his book, De chymicorum cum Aristotelicis et Galenicis consensu ac dissensu, published in Wittenberg in 1619, stated: Nevertheless, most of those who today would be labelled iatrochemists follow Petrus Severinus, who has undertaken to bring the doctrines, expressed here and there by Paracelsus, back into the form of art, better than Paracelsus himself. -

Copernicus' First Friends: Physical Copernicanism

Filozofski vestnik Volume/Letnik XXV • Number/Številka 2 • 2004 • 143–166 COPERNICUS’ FIRST FRIENDS: PHYSICAL COPERNICANISM FROM 1543 TO 1610 Katherine A. Tredwell and Peter Barker Early assessments of the Copernican Revolution were hampered by the failure to understand the nature of astronomy in the sixteenth century, as scholars took statements made in praise of Copernicus to be implicit endorsements of his heliocentric cosmology. Gradually this view has been supplanted by the ac- knowledgement that many supposed partisans of Copernicus only endorsed the use of his astronomical models for the calculation of apparent planetary positions, while rejecting or remaining silent on the reality of heliocentrism. A classic example of this shift in historiography concerns Erasmus Reinhold (1511–1553), a professor of mathematics at the University of Wittenberg. Re- inhold’s use of Copernican models in his Prutenic Tables (Tabulae prutenicae, 1551) has led to the mistaken belief that he sanctioned a Sun-centered cos- mology as well. Careful reassessment of his published writings has revealed that he commended certain aspects of Copernicus’ work, such as the elimi- nation of the equant, but showed no interest in heliocentrism (Westman, 1975: pp. 174–178). Other supposed Copernicans, such as Robert Recorde (c. 1510–1558), expressed some openness to the Earth’s motion but left no clear indication of what they thought to be the true system of the world (Rus- sell, 1972: pp. 189–191). Between the publication of Copernicus’ epoch-making book On the Revo- lutions of the Celestial Orbs (De revolutionibus orbium coelestium) in 1543 and the year 1610, only a handful of individuals can be identified with certainty as Copernicans, in the sense that they considered heliocentrism to be physically real and not merely a calculational convenience. -

Introduction

On the Law of Nature in the Three States of Life E. J. Hutchinson and Korey D. Maas Introduction Niels Hemmingsen (1513–1600) and the Development of Lutheran Natural-Law Teaching Because the Danish Protestant theologian and philosopher Niels Hemmingsen (1513–1600) is today little known outside his homeland, some of the claims made for his initial importance and continuing impact can appear rather extravagant. He is described, for example, not only as having “dominated” the theology of his own country for half a century1 but more broadly as having been “the greatest builder of systems in his generation.”2 In the light of this indefatigable system building, he has further been credited with (or blamed for) initiating modern trends in critical biblical scholarship,3 as well as for being “one of the founders 1 Lief Grane, “Teaching the People—The Education of the Clergy and the Instruction of the People in the Danish Reformation Church,” in The Danish Reformation against Its International Background, ed. Leif Grane and Kai Hørby (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1990), 167. 2 F. J. Billeskov Janson, “From the Reformation to the Baroque,” in A History of Danish Literature, ed. Sven Hakon Rossel (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 79. 3 Kenneth Hagen, “De Exegetica Methodo: Niels Hemmingsen’s De Methodis (1555),” in The Bible in the Sixteenth Century, ed. David C. Steinmetz (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990), 196. iii 595 Scholia iv Introduction of modern jurisprudence.”4 Illuminating this last claim especially are the more -

Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm

Medical History, 1995, 39: 78-94 The Reception of Paracelsianism in early modem Lutheran Denmark: from Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm OLE PETER GRELL* Retrospectively, the appointment in 1571 of the two Paracelsian physicians, Peter Severinus (1540-1602) and Johannes Philip Pratensis (1543-1576), as royal physician to King Frederik II of Denmark-Norway and professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen respectively, can be seen to have marked not only the introduction of Paracelsianism, but also the start of the medical renaissance in Denmark. The importance of Peter Severinus and his work Idea medicina philosophica? (Basle, 1571) in making Paracelsus's ideas acceptable within the scholarly community of early modem Europe was widely recognized by contemporary admirers, as well as antagonists. Since contemporaries labelled Paracelsus the Luther of medicine, it is tempting to widen the analogy and see Severinus as Melanchthon to Paracelsus's Luther. Like Melanchthon, Severinus eased and modified his mentor's ideas, thereby making them acceptable within the political and scholarly world where hitherto they had lacked appeal. Thus, the Heidelberg-based physician and theologian Thomas Erastus recommended Severinus's book as the most palatable face of Paracelsianism as early as 1579,' while another influential critic, the Wittenberg professor of medicine, Daniel Sennert, in his book, De chymicorum cum Aristotelicis et Galenicis consensu ac dissensu, published in Wittenberg in 1619, stated: Nevertheless, most of those who today would be labelled iatrochemists follow Petrus Severinus, who has undertaken to bring the doctrines, expressed here and there by Paracelsus, back into the form of art, better than Paracelsus himself. -

Johannes Kepler's Horoscope Collection

CULTURE AND COSMOS A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy Vol. 14 no 1 and 2, Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter 2010 Published by Culture and Cosmos and the Sophia Centre Press, in partnership with the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, in association with the Sophia Centre for the Study of Cosmology in Culture, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Faculty of Humanities and the Performing Arts Lampeter, Ceredigion, Wales, SA48 7ED, UK. www.cultureandcosmos.org Cite this paper as: Friederike Boockmann, ‘Johannes Kepler’s Horoscope Collection’ (trans. Patrick Boner, additional ediing Dorian Greenbaum), Culture and Cosmos , Vol. 14 no 1 and 2, Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter 2010, pp. 1-32. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue card for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publishers. ISSN 1368-6534 Printed in Great Britain by Lightning Source Copyright 2018 Culture and Cosmos All rights reserved Johannes Kepler’s Horoscope Collection _________________________________________________________________ Friederike Boockmann Updated and translated from the German by Patrick * J. Boner; additional editing by Dorian Greenbaum Astrology in Kepler’s time (1571-1630) experienced a second highpoint in its history. Kepler the astronomer also had to deal extensively with astrological questions. From these questions came his theoretical writings on astrology, De fundamentis astrologiae certioribus (1602), Antwort auf Röslini Diskurs (1609), Tertius interveniens (1610)1 and Harmonice mundi (1619), Book 4, Chapter 7.2 However, while these writings have been considered in numerous scholarly studies,3 Kepler’s dealings with * Boockmann’s original article appeared as ‘Die Horoskopsammlung von Johannes Kepler’, in Miscellanea Kepleriana. -

Academic Ancestry of Christopher John Nitta Generation

Academic Ancestry of Christopher John Nitta Legend Name Generation Institution Institution National Seal Degree Year "Thesis Title" Flag Domingo (St. Dominic) de Guzmán 49th Universidad de Palencia / Ordo Praedicatorum 1194 Réginald de Orléans 48th Université de Paris / Ordo Praedicatorum 1206 Jordanus (Jordan of Saxony) 47th Université de Paris / Ordo Praedicatorum 1220 Albertus Magnus Johannes Pagus 46th Università di Padova / Université de Paris Université de Paris Nilos Kabasilas Th.D. 1245 (Promoted posthumously to Doctor Universalis by Catholic Church in 1931) M.A. 1220 Petrus Ferrandi Hispanus 45th Université de Paris Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus "Tractatus" 1347 (Received first premiership from Byzantine Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos in 1347) John Duns Scotus Georgios Plethon Gemistos 44th University of Oxford / Université de Paris 1380 1303 1393 "Nómoi (Book of Laws)" William of Ockham Basilios Bessarion 43rd University of Oxford Manuel Chrysoloras Mystras (Never completed degree; known for Ockham's razor) (Born in Constantinople, left in 1396 to each at Università di Firenze ) 1436 Grégoire de Rimini Johannes Argyropoulos 42nd Université de Paris Guarino da Verona Università di Padova M.A. 1323 1408 Th.D. 1444 Pierre d'Ailly Université de Paris Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino 41st M.A. 1368 Università di Padova Cristoforo Landino Università di Firenze Collège de Navarre 1416 L'Accademia Neoplatonica M.A. 1462 Th.D. 1381 Paulus Venetus Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano 40th University of Oxford / Università di Padova Constantinople / Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1395 M.A. 1433 M.A. 1477 Heinrich von Langenstein Leo Outers Sigismondo Polcastro Université de Paris Université Catholique de Louvain Gaetano da Thiene Università di Padova Moses Perez Demetrios Chalcocondyles Scipione Fortiguerra 39th M.A. -

Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm

Medical History, 1995, 39: 78-94 The Reception of Paracelsianism in early modem Lutheran Denmark: from Peter Severinus, the Dane, to Ole Worm OLE PETER GRELL* Retrospectively, the appointment in 1571 of the two Paracelsian physicians, Peter Severinus (1540-1602) and Johannes Philip Pratensis (1543-1576), as royal physician to King Frederik II of Denmark-Norway and professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen respectively, can be seen to have marked not only the introduction of Paracelsianism, but also the start of the medical renaissance in Denmark. The importance of Peter Severinus and his work Idea medicina philosophica? (Basle, 1571) in making Paracelsus's ideas acceptable within the scholarly community of early modem Europe was widely recognized by contemporary admirers, as well as antagonists. Since contemporaries labelled Paracelsus the Luther of medicine, it is tempting to widen the analogy and see Severinus as Melanchthon to Paracelsus's Luther. Like Melanchthon, Severinus eased and modified his mentor's ideas, thereby making them acceptable within the political and scholarly world where hitherto they had lacked appeal. Thus, the Heidelberg-based physician and theologian Thomas Erastus recommended Severinus's book as the most palatable face of Paracelsianism as early as 1579,' while another influential critic, the Wittenberg professor of medicine, Daniel Sennert, in his book, De chymicorum cum Aristotelicis et Galenicis consensu ac dissensu, published in Wittenberg in 1619, stated: Nevertheless, most of those who today would be labelled iatrochemists follow Petrus Severinus, who has undertaken to bring the doctrines, expressed here and there by Paracelsus, back into the form of art, better than Paracelsus himself. -

The Book Everybody Read: Vernacular Translations Of

JHA0010.1177/0021828614567419Journal for the History of AstronomyCrowther et al. 567419research-article2015 Article JHA Journal for the History of Astronomy 2015, Vol. 46(1) 4 –28 The Book Everybody Read: © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Vernacular Translations of sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0021828614567419 Sacrobosco’s Sphere in the jha.sagepub.com Sixteenth Century Kathleen Crowther University of Oklahoma, Department of the History of Science, USA Ashley Nicole McCray University of Oklahoma, Department of the History of Science, USA Leila McNeill Independent scholar, Texas, USA Amy Rodgers University of Oklahoma, Department of the History of Science, USA Blair Stein University of Oklahoma, Department of the History of Science, USA Abstract This article presents four detailed case studies of sixteenth-century vernacular translations of Sacrobosco’s De sphaera. Previous scholarship has highlighted the important role of Sacrobosco’s Sphere in medieval and early modern universities, where it served as an introductory astronomy text. We argue that the Sphere was more than a university teaching text. It was translated many times and was accessible to a wide range of people. The popularity of the Sphere suggests widespread interest in cosmological questions. We suggest that the text was a profitable one for early modern printers, who strove to identify books that would be reliable sellers. We also argue that the Sphere was not a static text. Rather, translators and editors added commentaries and other supplemental material that corrected and updated Sacrobosco’s original text and Corresponding author: Kathleen Crowther, Department of the History of Science, University of Oklahoma, 601 Elm Avenue, Room 625, Norman, OK 73019, USA.