Thomas Satterwhite Noble (1835- 1907): Reconstructed Rebel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Arts Administration Master's Reports Arts Administration Program 12-2015 An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art Grace Rennie University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts Part of the Arts Management Commons Recommended Citation Rennie, Grace, "An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art" (2015). Arts Administration Master's Reports. 185. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts/185 This Master's Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Master's Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Master's Report has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Administration Master's Reports by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art An Internship Academic Report Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration by Grace Rennie B.F.A. School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2011 December 2015 Table of Contents -

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

Immaculate Defamation: the Case of the Alton Telegraph

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 1 Issue 3 2014 Immaculate Defamation: The Case of the Alton Telegraph Alan M. Weinberger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan M. Weinberger, Immaculate Defamation: The Case of the Alton Telegraph, 1 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 583 (2014). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V1.I3.4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMACULATE DEFAMATION: THE CASE OF THE ALTON TELEGRAPH By: Alan M. Weinberger* ABSTRACT At the confluence of three major rivers, Madison County, Illinois, was also the intersection of the nation’s struggle for a free press and the right of access to appellate review in the historic case of the Alton Telegraph. The newspaper, which helps perpetuate the memory of Elijah Lovejoy, the first martyr to the cause of a free press, found itself on the losing side of the largest judgment for defamation in U.S. history as a result of a story that was never published in the paper—a case of immaculate defamation. Because it could not afford to post an appeal bond of that magnitude, one of the oldest family-owned newspapers in the country was forced to file for bankruptcy to protect its viability as a going concern. -

Investigative Reporter to Visit Hill College Adds Cinema Studies Minor

Campus SECOND ANNUAL DRAG BALL Students jobs: passion win grants versus pay for bus. By LAUREN FIORELU proposals ASST. NEWS EDITOR With hundreds of paid posi- By LORI MERVIN tions existing on campus, it 's not NEWS STAFF difficult to find work on the Hill, and students at the College don't In order to encourage young hesitate to apply. But those entrepreneurship on the Hill, searching for their passion often Mark Johnson *96 and Joe have to overlook compensation Boulous '68 donated $15,000 and put in more time than the toward the College's first En- College will pay for. As students trepreneurial Alliance Busi- discover their working niche on ness Competition, which took campus with a job they are per- place April 9. sonally invested in, balancing be- The competition included tween work and study time can nine student business pro- become more of a struggle. But posals in various stages of the more their work is motivated planning. In order to partake by personal interest, the less they in the competition, students care about the money. were required to participate The College employs more than in a series of entrepreneurial 1,100 students on campus a year, classes offered through the according to the College website's College's Career Center. student employment page. "I al- These classes focused on the » I CJUIUUUUWW UW UHA ways talk on my tours about jobs at Members of the Male Athletes Against Violence (MAAV) group dress up and perform a fashion show as part of the Drag Ball basics of entrepreneurship. -

Scenic and Historic Illinois

917.73 BBls SCENIC AND== HISTORIC ILLINOIS With Abraham lincoln Sites and Monuments Black Hawk War Sites ! MADISON. WISCONSIN 5 1928 T»- ¥>it-. .5^.., WHm AUNOIS HISTORICAL SIISYIT 5 )cenic and Historic Illinois uic le to One TKousand Features of Scenic, Historic I and Curious Interest in Illinois w^itn ADraKam Lincoln Sites and Monuments Black Hawk War Sites Arranged by Cities and Villages CHARLES E. BROWN AutKor, Scenic and Historic Wisconsin Editor, TKe Wisconsin ArcKeologist The MusKroom Book First Edition Published by C. E. BROWN 201 1 CKadbourne Avenue Madison, Wisconsin Copyrighted, 1928 t' FOREWORD This booklet is issued with the expectation that prove of ready reference service to those who motor in Illinois. Detailed information of the Ian monuments, etc. listed may be obtained from th' cations of the Illinois Department of Conse Illinois State Historical Society, State Geological Chicago Association of Commerce, Chicago H. Society, Springfield Chamber of Commerce, an local sources. Tourists and other visitors are requested to re that all of the landmarks and monuments mentior many others not included in this publication, are lie heritage and under the protection of the state the citizens of the localities in which they occ the Indian mounds some are permanently pr' The preservation of others is encouraged. Tl ploration, when desirable, should be undertaken ganizations and institutions interested in and i equipped for such investigations. Too great a the States' archaeological history and to educat already resulted from the digging* in such an Indian landmarks by relic hunters. The mutile scenic and historic monuments all persons shoul in preventing. -

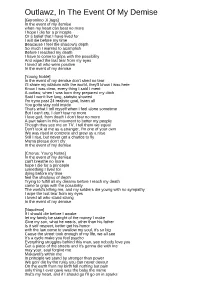

Outlawz, in the Event of My Demise

Outlawz, In The Event Of My Demise [Geronimo Ji Jaga] In the event of my demise when my heart can beat no more I hope I die for a princeple Or a belief that I have lived for I will die before my time Beacause I feel the shadow's depth So much I wanted to acomplish Before I reached my death I have to come to grips with the possibility And wiped the last tear from my eyes I loved all who were positive In the event of my demise [Young Noble] In the event of my demise don't shed no tear I'll share my wizdom with the world, they'll know I was here Know I was clear, every thing I said I ment A outlaw, when I was born they prepared my ditch Said I won't live long, statistic showed I'm tryna past 24 realistic goal, listen all You gotta stay cold inside That's what I tell myself when I feel alone sometime But I can't cry, I don't tear no more I love god, from death I don't fear no more A part taken in this movment to better my people Though they see me on TV, I tell them we equal Don't look at me as a stranger, I'm one of your own We was rised in concrete and grew as a rose Still I rise, but never get a chance to fly Mama please don't cry In the event of my demise [Chorus: Young Noble] In the event of my demise can't breathe no more hope I die for a princeple something I lived for dying before my time feel the shadows of depth Trying to fulfill all my dreams before I reach my death came to grips with the possibility The world's killing me, and my soldiers die young with no sympathy I wipe the last tear from my eyes I loved all who stand strong -

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

MARGARET GARNER a New American Opera in Two Acts

Richard Danielpour MARGARET GARNER A New American Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Toni Morrison Based on a true story First performance: Detroit Opera House, May 7, 2005 Opera Carolina performances: April 20, 22 & 23, 2006 North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center Stefan Lano, conductor Cynthia Stokes, stage director The Opera Carolina Chorus The Charlotte Contemporary Ensemble The Charlotte Symphony Orchestra The Characters Cast Margaret Garner, mezzo slave on the Gaines plantation Denyce Graves Robert Garner, bass baritone her husband Eric Greene Edward Gaines, baritone owner of the plantation Michael Mayes Cilla, soprano Margaret’s mother Angela Renee Simpson Casey, tenor foreman on the Gaines plantation Mark Pannuccio Caroline, soprano Edward Gaines’ daughter Inna Dukach George, baritone her fiancée Jonathan Boyd Auctioneer, tenor Dale Bryant First Judge , tenor Dale Bryant Second Judge, baritone Daniel Boye Third Judge, baritone Jeff Monette Slaves on the Gaines plantation, Townspeople The opera takes place in Kentucky and Ohio Between 1856 and 1861 1 MARGARET GARNER Act I, scene i: SLAVE CHORUS Kentucky, April 1856. …NO, NO. NO, NO MORE! NO, NO, NO! The opera begins in total darkness, without any sense (basses) PLEASE GOD, NO MORE! of location or time period. Out of the blackness, a large group of slaves gradually becomes visible. They are huddled together on an elevated platform in the MARGARET center of the stage. UNDER MY HEAD... CHORUS: “No More!” SLAVE CHORUS THE SLAVES (Slave Chorus, Margaret, Cilla, and Robert) … NO, NO, NO MORE! NO, NO MORE. NO, NO MORE. NO, NO, NO! NO MORE, NOT MORE. (basses) DEAR GOD, NO MORE! PLEASE, GOD, NO MORE. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

The Americans

INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1861. Seven Southern states have seceded from the Union over the issues of slavery and states rights. They have formed their own government, called the Confederacy, and raised an army. In March, the Confederate army attacks and seizes Fort Sumter, a Union stronghold in South Carolina. President Lincoln responds by issuing a call for volun- teers to serve in the Union army. Can the use of force preserve a nation? Examine the Issues • Can diplomacy prevent a war between the states? • What makes a civil war different from a foreign war? • How might a civil war affect society and the U.S. economy? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 11 links for more information about The Civil War. 1864 The 1865 Lee surrenders to Grant Confederate vessel 1864 at Appomattox. Hunley makes Abraham the first successful Lincoln is 1865 Andrew Johnson becomes submarine attack in history. reelected. president after Lincoln’s assassination. 1863 1864 1865 1864 Leo Tolstoy 1865 Joseph Lister writes War and pioneers antiseptic Peace. surgery. The Civil War 337 The Civil War Begins MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names The secession of Southern The nation’s identity was •Fort Sumter •Shiloh states caused the North and forged in part by the Civil War. •Anaconda plan •David G. Farragut the South to take up arms. •Bull Run •Monitor •Stonewall •Merrimack Jackson •Robert E. Lee •George McClellan •Antietam •Ulysses S. Grant One American's Story On April 18, 1861, the federal supply ship Baltic dropped anchor off the coast of New Jersey. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production.