Transcript a Pinewood Dialogue with Brad Bird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

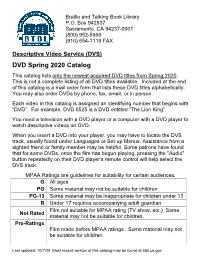

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children. -

Pixar's 22 Rules of Story Analyzed

PIXAR’S 22 RULES OF STORY (that aren’t really Pixar’s) ANALYZED By Stephan Vladimir Bugaj www.bugaj.com Twitter: @stephanbugaj © 2013 Stephan Vladimir Bugaj This free eBook is not a Pixar product, nor is it endorsed by the studio or its parent company. Introduction. In 2011 a former Pixar colleague, Emma Coats, Tweeted a series of storytelling aphorisms that were then compiled into a list and circulated as “Pixar’s 22 Rules Of Storytelling”. She clearly stated in her compilation blog post that the Tweets were “a mix of things learned from directors & coworkers at Pixar, listening to writers & directors talk about their craft, and via trial and error in the making of my own films.” We all learn from each other at Pixar, and it’s the most amazing “film school” you could possibly have. Everybody at the company is constantly striving to learn new things, and push the envelope in their own core areas of expertise. Sharing ideas is encouraged, and it is in that spirit that the original 22 Tweets were posted. However, a number of other people have taken the list as a Pixar formula, a set of hard and fast rules that we follow and are “the right way” to approach story. But that is not the spirit in which they were intended. They were posted in order to get people thinking about each topic, as the beginning of a conversation, not the last word. After all, a hundred forty characters is far from enough to serve as an “end all and be all” summary of a subject as complex and important as storytelling. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

National Film Registry

National Film Registry Title Year EIDR ID Newark Athlete 1891 10.5240/FEE2-E691-79FD-3A8F-1535-F Blacksmith Scene 1893 10.5240/2AB8-4AFC-2553-80C1-9064-6 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894 10.5240/4EB8-26E6-47B7-0C2C-7D53-D Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 10.5240/B1CF-7D4D-6EE3-9883-F9A7-E Rip Van Winkle 1896 10.5240/0DA5-5701-4379-AC3B-1CC2-D The Kiss 1896 10.5240/BA2A-9E43-B6B1-A6AC-4974-8 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 10.5240/CE60-6F70-BD9E-5000-20AF-U Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 10.5240/65B2-B45C-F31B-8BB6-7AF3-S President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 10.5240/C276-6C50-F95E-F5D5-8DCB-L The Great Train Robbery 1903 10.5240/7791-8534-2C23-9030-8610-5 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 10.5240/F72F-DF8B-F0E4-C293-54EF-U A Trip Down Market Street 1906 10.5240/A2E6-ED22-1293-D668-F4AB-I Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 10.5240/4D64-D9DD-7AA2-5554-1413-S San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 10.5240/69AE-11AD-4663-C176-E22B-I A Corner in Wheat 1909 10.5240/5E95-74AC-CF2C-3B9C-30BC-7 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 10.5240/0807-6B6B-F7BA-1702-BAFC-J Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 10.5240/C704-BD6D-0E12-719D-E093-E Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 10.5240/A8C0-4272-5D72-5611-D55A-S White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 10.5240/0132-74F5-FC39-1213-6D0D-Z Little Nemo 1911 10.5240/5A62-BCF8-51D5-64DB-1A86-H A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 10.5240/7E6A-CB37-B67E-A743-7341-L From the Manger to the Cross 1912 10.5240/5EBB-EE8A-91C0-8E48-DDA8-Q The Cry of the Children 1912 10.5240/C173-A4A7-2A2B-E702-33E8-N -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

Why Shop Ar Ound?

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Wednesday, Wednesday, Northwoods Furniture Gallery (715) 477-2573 WI 54521 45S, Eagle River, 630 US Hwy. Northwoods Furniture Outlet (715) 479-3971 WI 54521 Ln., Eagle River, Twilite 1171 June 13, 2018 13, June (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS SAVINGS W A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A SERVICE SERVICE (See store for details) W northwoods-furniture.com 12-Month No-Interest Financing Available 12-Month No-Interest Financing Open Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 a.m. - 3 p.m. Open Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 SELECTION NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL SIMPLY THE BEST PRICES TO BE FOUND THE BEST PRICES TO SIMPLY WHY SHOP AROUND? © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, More Great Deals at Parsons! JUST ARRIVED! OTHER GREAT VALUES 2018 Chevrolet Equinox LT 2013 Chevrolet Camaro Certified Preowned Only 14,789 miles 4 Available 4-Cylinder, Stk# 661 push-button $17,987 All-Wheel-Drive, Backup Camera and Heated Seats 2015 Chevrolet $ Suburban LT 4x4 Starting at 24,990 Stk# 573 $36,648 Stk# 399 MORE GREAT DEALS for Less than $15,000 2015 GMC 2005 Dodge Grand Caravan................................................Stk# 442 $2,976 Terrain SLT AWD 2011 Chevrolet Equinox AWD.............................................Stk# 476 $5,689 Stk# 321 2009 Pontiac Vibe ........................................................................Stk# -

Harun Farocki and Cinema As Chiro-Praxis

Journal of Aesthetics & Culture ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/zjac20 “A new image of man”: Harun Farocki and cinema as chiro-praxis Henrik Gustafsson To cite this article: Henrik Gustafsson (2021) “A new image of man”: Harun Farocki and cinema as chiro-praxis, Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 13:1, 1841977, DOI: 10.1080/20004214.2020.1841977 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1841977 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 29 Dec 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 137 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zjac20 JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS & CULTURE 2021, VOL. 13, 1841977 https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1841977 “A new image of man”: Harun Farocki and cinema as chiro-praxis Henrik Gustafsson Media and Documentation Science Department of Language and Culture, The Arctic University, Tromsø, Norway ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In Harun Farocki’s lifelong study of the mute language of manual expressions, the human Animation; anthropology; hand is explored not only as a versatile tool, but as a repository of social memory, a topos in automation; gesture; Harun the genealogy of the moving image, and a critical agent in the theory and practice of Farocki; hand; imagination; filmmaking itself. While cinema distinguished itself from previous artistic media through its operational chain; capacity to salvage and store everyday gestures for later scrutiny, accruing a Bilderschatz for operational image; social future anthropological and archaeological research, it was also integral to an ongoing process memory; soft montage that spurred the progressive withdrawal of the human hand from the manufacturing of images. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

„No Story Comes from Nowhere‟, or, the Dentist from Finding Nemo: Ambivalent Originality in Four Contemporary Works Jens Fredslund, University of Aarhus Abstract This paper offers a perspective on a range of contemporary developments and articulations of the phenomenon of intertextuality in fiction and film. Using as backdrop a brief discussion of different intertextual motifs in Salman Rushdie‟s Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990), Paul Auster‟s Travels in the Scriptorium (2006) and Pixar‟s animated short film Boundin’ (2004), it moves on to discuss the highly intertextual relation between the works of Swiss writer Robert Walser and the contemporary American experimentalist Alison Bundy. The paper thus problematizes and qualifies the line of demarcation supposedly existing between texts or works of art and aims to expand and exemplify the scope of reference, citation and paraphrase inherent in the overall concept of intertextuality. This paper springs from a baffled encounter with four postmodern works which all revolve around the theme of ambivalent originality. The four works portray origin and the original as regurgitation and as a result or an end point. And they describe the site of origin as both primary and secondary, and as disturbingly identical to what appears to repeat it. This undermining of the stability and integrity of the point of origin is presented as a thoroughly relational event. Origin is seen to lose its originality in the interaction with its surroundings, echoing Graham Allen speaking of the „relationality, interconnectedness and interdependence in modern cultural life‟ (5). In this paper I discuss four different expressions of this „interconnectedness‟—expressions which each in their own way portray or testify to patterns of intertextuality. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor .