Michael Barba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children. -

Why Shop Ar Ound?

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Wednesday, Wednesday, Northwoods Furniture Gallery (715) 477-2573 WI 54521 45S, Eagle River, 630 US Hwy. Northwoods Furniture Outlet (715) 479-3971 WI 54521 Ln., Eagle River, Twilite 1171 June 13, 2018 13, June (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS SAVINGS W A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A SERVICE SERVICE (See store for details) W northwoods-furniture.com 12-Month No-Interest Financing Available 12-Month No-Interest Financing Open Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 a.m. - 3 p.m. Open Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 SELECTION NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL SIMPLY THE BEST PRICES TO BE FOUND THE BEST PRICES TO SIMPLY WHY SHOP AROUND? © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, More Great Deals at Parsons! JUST ARRIVED! OTHER GREAT VALUES 2018 Chevrolet Equinox LT 2013 Chevrolet Camaro Certified Preowned Only 14,789 miles 4 Available 4-Cylinder, Stk# 661 push-button $17,987 All-Wheel-Drive, Backup Camera and Heated Seats 2015 Chevrolet $ Suburban LT 4x4 Starting at 24,990 Stk# 573 $36,648 Stk# 399 MORE GREAT DEALS for Less than $15,000 2015 GMC 2005 Dodge Grand Caravan................................................Stk# 442 $2,976 Terrain SLT AWD 2011 Chevrolet Equinox AWD.............................................Stk# 476 $5,689 Stk# 321 2009 Pontiac Vibe ........................................................................Stk# -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor . -

Sunday Morning Grid 7/19/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

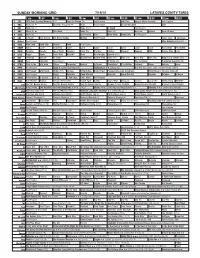

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/19/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Gospel Music Presents Paid Program 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Beach Volleyball Golf 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Open Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Miss Nobody (2010) (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Rudy ››› (1993) (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Zoom › (2006) Tim Allen. (PG) Chimpanzee ›› (2012) (G) Ben Hur Un príncipe judío enfrenta traición. -

Sunday Morning Grid 11/23/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

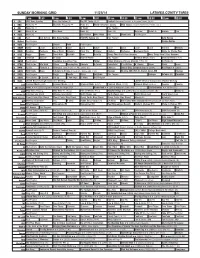

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/23/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Houston Texans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) World/Adventure Sports MLS Soccer: Eastern Conference Finals, Leg 1 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Auto Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Pirates-Worlds 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Monkey 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Barbecue Heirloom Meals Home for Christy Rost 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (9:50) (N) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dhabi. -

Honor Roll 2006

i annual report Jennifer Rodriquez, age 3 gifts Childrens hospiTal los angeles honor roll of donors for the time period of January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2006 in gratitude and recognition The patients, families, staff and Board of Trustees of Childrens Hospital Los Angeles are grateful to the many people who help us build for the future and provide clinical care, research and medical education through their financial support. We recognize esteemed individuals, organizations, corporations and foundations for their generosity during the 2006 calendar year. This Honor Roll lists donors who contributed at least $1,000 in cash gifts, pledges or pledge payments. To view the Red Wagon Society Honor Roll of Donors, which lists gifts of $150 to $999, please visit the electronic version of the Honor Roll at www.ChildrensHospitalLA.org/honorroll2006.pdf. Foregoing individual recognition, we also extend thanks to those who made generous contribu- tions directly to one of our Associate and Affiliate, or allied groups. Children’s Miracle Network (CMN) gifts to CMN National will be recognized in the next issue of Imagine. In spite of our best efforts, errors and omissions may occur. Please inform us of any inaccuracies by contacting Marie Logan, director of Donor Relations, at (323) 671-1733, or [email protected]. • | imagine spring 07 $10,000,000 and above The Sharon D. Lund Foundation Confidence Foundation Randy and Erika Jackson Anonymous Friend The Harold McAlister Charitable Corday Foundation Foundation i Foundation Kenneth and Sherry Corday Johnson & Johnson $4,000,000 to $9,999,999 Mrs. J. Thomas McCarthy Mr. -

Carroll Barnes (March 1–March 15) Carroll Barnes (1906–1997) Worked in Various Careers Before Turning His Attention to Sculpture Full Time at the Age of Thirty

1950 Sculpture in Wood and Stone by Carroll Barnes (March 1–March 15) Carroll Barnes (1906–1997) worked in various careers before turning his attention to sculpture full time at the age of thirty. His skills earned him a position as a professor of art at the University of Texas and commissions from many public and private institutions. His sculptures are created in various media, such as Lucite and steel. This exhibition of the California-based artist’s work presented thirty-seven of his sculptures. Barnes studied with Carl Milles (1875– 1955) at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. [File contents: exhibition flier] Color Compositions by June Wayne (March) June Wayne’s (1918–2011) work received publicity in an article by Jules Langsner, who praised her for developing techniques of drawing the viewer’s eye through imagery and producing a sense of movement in her subjects. Her more recent works (as presented in the show) were drawn from the dilemmas to be found in Franz Kafka’s works. [File contents: two articles, one more appropriate for a later show of 1953 in memoriam Director Donald Bear] Prints by Ralph Scharff (April) Sixteen pieces by Ralph Scharff (1922–1993) were exhibited in the Thayer Gallery. Some of the works included in this exhibition were Apocrypha, I Hate Birds, Walpurgisnacht, Winter 1940, Nine Cats, and Four Cows and Tree Oranges. Watercolors by James Couper Wright (April 3–April 15) Eighteen of James Couper Wright’s (1906–1969) watercolors were presented in this exhibition. Wright was born in Scotland, but made his home in Southern California for the previous eleven years. -

Ormond Beach, FL 32176-4141 CELL: 386.441.7024 [email protected]

THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF LIONS CLUBS OFFICIAL DIRECTORY DISTRICT 35-O FLORIDA AND THE BAHAMAS Helene Thompson District Governor 35-O 2018-2019 www.lionsofflorida.org www.lionsclubs.org 2018—2019 District 35-N District Governor Helen Thompson and Gini Black International President Gudrun Bjort Yngvadottie and (Dr Jon Bjarni Thorsteinsson, PID) 3 District 35-N Directory TABLE OF CONTENTS TOPIC PAGE District, MD35, and International Meetings ——————————–—- 6 DISTRICT GOVERNOR ———————————————————– 3 1st Vice District Governor——————————————————— 3 2nd Vice District Governor ——————————————————- 3 District 35 District Governors ————————————————- 194 District 35 1st Vice District Governors ————————————-- 193 District 35 2nd Vice District Governors ————————————- 192 District Secretary ——————————————————————- 7 District Treasurer ——————————————————————- 7 District Advisors ——————————————————————— 7 District Chaplain ——————————————————————— 8 Contest & Award Rules ———————————————————- 98 Council Chairperson ———————————————————— 98 Crusader Award ——————————————————————- 101 District 35O Club Meetings —————————————————— 17 District 35O Clubs ———————————————————-——- 18 District 35O Leo Clubs ———————————————————- 67 District 35O and MD Committees ——————————————— 69 District Tail Twister —————————————————————– 8 GAT, GLT , GMT AND GST —————————————————— 8 Lions Code of Ethics ———————————————————— 10 Lions Clubs International ——————————————————- 10 Lions Induction Ceremony —————————————————— 15 Lions International Purposes ————————————————— 11 -

Il Piccolo Principe

presenta Tratto dall’omonimo romanzo di Antoine de Saint-Exupéry un film di MARK OSBORNE USCITA 1 GENNAIO 2016 Tutti i materiali stampa sono scaricabili dal sito www.luckyred.it/press UFFICIO STAMPA Alessandra Tieri (+39 335.8480787 [email protected]) Georgette Ranucci (+39 335.5943393 [email protected]) Olga Brucciani (+39 345.8670603 [email protected]) CAST TECNICO Regia MARK OSBORNE Tratto dal romanzo di ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY Sceneggiatura BOB PERSICHETTI, IRENA BRIGNULL Scenografia LOU ROMANO, CÉLINE DESRUMAUX Montatore MATTHEW LANDON Disegnatore dei personaggi PETER DE SEVE Supervisore animazione HIDETAKA YOSUMI dei personaggi in 3D Supervisore dell’animazione in 3D JASON BOOSE Supervisore delle luci in 3D ADEL ABADA Direttore creativo per JAMIE CALIRI l’animazione in stop motion Disegnatore scenografie ALEX JUHASZ e personaggi in stop motion Capo animatore in stop motion ANTHONY SCOTT Una produzione ORANGE STUDIO, M6 FILMS, LPPTV, ON ANIMATION STUDIOS Co-produzione LUCKY RED in collaborazione con RTI 2 EDIZIONE ITALIANA a cura di Margutta Digital International Toni Servillo L’Aviatore Paola Cortellesi La Mamma Stefano Accorsi La Volpe Micaela Ramazzotti La Rosa Alessandro Gassmann Il Serpente Giuseppe Battiston L’Uomo d’affari Angelo Pintus Il Sig Principe Pif Il Re Alessandro Siani L’Uomo vanitoso Lorenzo D’Agata Il Piccolo principe Vittoria Bartolomei La Bambina Carlo Valli L’Insegnante Carlo Reali L’Esaminatore Melissa Maccari La Vicina di casa Stefano Oppedisano Il Vicino di casa Adattamento dialoghi Carlo Valli Direzione del doppiaggio Carlo Valli Assistente al doppiaggio Maria Grazia Napolitano Sincronizzazione Paolo Brunori Fonico di mixage Francesco Tumminello Fonico di doppiaggio Federico Costantini 3 SINOSSI Ed ecco il mio segreto. -

FOR YOUR INFORMATION: Government Documents Is Giving Away Superseded NOAA Coastal Chart Maps from Various Areas

Volume 33, No.13 Summer 2007 In Touch News for employees of the Clemson University Libraries Deanna Swafford was Born in Seneca. She is Married and has 2 boys ages 10 & 6. Deanna loves fishing & playing baseball (she usually Don Brewer lives in Seneca. He is married with beats her husband in baseball). She loves 4 children & 4 grand kids. He was a motiva- spending time with her family, and her favorite tional speaker and has traveled all over the book is Where the Red Fern grows. She re- world. Don really wanted to enjoy life, cently saw the DVD and cried all over again. and says he is perfectly happy to dust books and clean toilets. He loves the fact that he gets to go home to his wife and they can do whatever they like. Don likes to tinker around on cars, the last Joclyn Blackwell (Mrs. J) was born in West Philadelphia. She lived Germany and Atlanta, of which was a 68 super sport Camaro. before coming to Seneca. She has 3 children and 4 grandkids, one being raised by her. Jo- clyn was a baker for Aramark. She enjoys sew- ing and makes her own drapes! Joclyn says she Robert Caban was born in Puerto Rico, and loves football and baseball, her teams being the speaks fluent Spanish & English. He’s held the Washington Redskins and the Braves. leading role in two Puerto Rican movies, was in Havana Nights (name appears in cred- Richard Meares hails originally from Hamp- its) and worked on Pirates of the Caribbean ton Virginia. -

Kent Bingham's History with Disney

KENT BINGHAM’S HISTORY WITH DISNEY This history was started when a friend asked me a question regarding “An Abandoned Disney Park”: THE QUESTION From: pinpointnews [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Tuesday, March 22, 2016 3:07 AM To: Kent Bingham Subject: Photographer Infiltrates Abandoned Disney Park - Coast to Coast AM http://www.coasttocoastam.com/pages/photographer-infiltrates-abandoned-disney-park Could the abandoned island become an OASIS PREVIEW CENTER??? NOTE I and several of my friends have wanted to complete the EPCOT vision as a city where people could live and work. We have been looking for opportunities to do this for the last 35 years, ever since we completed EPCOT at Disney World on October 1, 1983. We intend to do this in a small farming community patterned after the life that Walt and Roy experienced in Marceline, Missouri, where they lived from 1906-1910. They so loved their life in Marceline that it became the inspiration for Main Street in Disneyland. We will call our town an OASIS VILLAGE. It will become a showcase and a preview center for all of our OASIS TECHNOLOGIES. We are on the verge of doing this, but first we had to invent the OASIS MACHINE. You can learn all about it by looking at our website at www.oasis-system.com . There you will learn that the OM provides water and energy (at minimum cost) that will allow people to grow their own food. This machine is a real drought buster, and will be in demand all over the world. This will provide enough income for us to build our OVs in many locations. -

Steven Van Varick District Governor 35-O 2021 – 2022

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF LIONS CLUBS OFFICIAL DIRECTORY DISTRICT 35-O FLORIDA, ARUBA, BAHAMAS, BONAIRE, AND CURACAO STEVEN VAN VARICK DISTRICT GOVERNOR 35-O 2021 – 2022 www.lionsclubs.org www.e-district.org/sites/35o/ www.lionsofflorida.club 0 Vision Statement To be the global leader in community and humanitarian service. Mission Statement To empower volunteers to serve their communities, meet humanitarian needs, encourage peace, and promote international understanding through Lions Clubs. Purpose To Organize, charter and supervise service clubs to be known as Lions clubs. To Coordinate the activities and standardize the administration of Lions clubs. To Create and foster a spirit of understanding among the peoples of the world. To Promote the principles of good government and good citizenship. To Take an active interest in the civic, cultural, social, and moral welfare of the community. To Unite the clubs in the bonds of friendship, good fellowship, and mutual understanding. To Provide a forum for the open discussion of all matters of public interest, provided, however, that partisan politics and sectarian religion shall not be debated by club members. To Encourage service-minded people to serve their community without personal financial reward, to encourage efficiency, and promote high ethical standards in commerce, industry, professions, public works, and private endeavors. 1 Table of Contents Vision Statement .......................................................................................................... 1 Mission Statement