Plymouth"S Master Plan (Complete Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing Smarter in Plymouth's Fifth Century; Master Plan 2004-2024

i PLYMOUTH PLANNING BOARD LORING TRIPP, Chair PAUL MCALDUFF NICHOLAS FILLA, Vice Chair WENDY GARPOW, ALTERNATE LARRY ROSENBLUM MALCOLM MCGREGOR PLYMOUTH MASTER PLAN COMMITTEE (2004) ENZO MONTI, Chair JOHN MARTINI RUTH AOKI, Vice Chair LARRY ROSENBLUM AILEEN DROEGE IRA SMITH SASH ERSKINE LORING TRIPP ELAINE SCHWOTZER LUTZ CHARLES VANDINI PREVIOUS MEMBERS OF THE MASTER PLAN COMMITTEE THOMAS BOTT JAMES MASON TERRY DONOGHUE MARY MULCAHY WILLIAM FRANKS DON QUINN ROBERTA GRIMES ROBERT REIFEISS REBECCA HALL TOM WALLACE GERRE HOOKER BRIAN WHITFIELD LOUISE HOUSTON MARK WITHINGTON TOM MALONEY DIRECTOR OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT LEE HARTMANN, AICP MASTER PLAN CONSULTANT MICHAEL PESSOLANO EDITING AND GRAPHIC DESIGN: GOODY, CLANCY & ASSOCIATES Photos: Larry Rosenblum Paul McAlduff Goody Clancy Thanks to everyone in Plymouth who helped create the Master Plan. GROWING SMARTER IN PLYMOUTH’S FIFTH CENTURY Town of Plymouth, Massachusetts Master Plan, 2004–2024 Plymouth Planning Board Master Plan Committee August 2006 Table of Contents VISION STATEMENT FOR PLYMOUTH, MASSACHUSETTS MASTER PLAN OVERVIEW 1. LAND USE 2. NATURAL RESOURCES 3. OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION 4. HISTORIC AND CULTURAL RESOURCES 5. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 6. PUBLIC FACILITIES/SERVICES 7. TRANSPORTATION APPENDIX: MAPS vi Vision Statement for Plymouth, Massachusetts In 20 years, the Town of Plymouth will be a beautiful, maturing community with vibrant and pleasant village centers, a preserved and enhanced historic heritage, long stretches of accessible coastline, integrated areas of commerce and compact housing, and vast, connected areas of open space set aside for preservation, outdoor activities, and appreciation of nature. Plymouth will retain its outstanding visual character, de- fined by clean ponds, rivers, wetlands, coastline, and forests. -

Event Information

Town of Plymouth, Massachusetts Department of Marine and Environmental Affairs 11 Lincoln Street, Plymouth, MA 02360 | 508-747-1620 10 Acre Public Ponds - Quick Reference Chart Acreage Pond Name Acreage Pond Name 10 Abner Pond 53 Island Pond (South) 31 Bartlett Pond (5) 24 King's Pond 20 Big Rocky Pond 81 Little Herring Pond (5)(6) 148 Big Sandy Pond (4)(6) 37 Little Island Pond 279 Billington Sea (4)(6) 50 Little Long Pond (5)(6) 98 Bloody Pond (2) (4) 10 Little Micaja Pond 74 Boot Pond (2)(6) 45 Little Pond (2) 19 Bump's Pond 12 Little Rocky Pond 18 Charge Pond 34 Little Sandy Pond 14 Clear Pond 66 Little South Pond (6) 50 College Pond (6) 224 Long Pond (3)(6) 25 Cook's Pond 20 Lout Pond 45 Curlew Pond 25 Micaja Pond 91 East Head Reservoir 26 Morey's Pond 27 Fearing Pond 10 Morton Pond 140 Federal Pond 22 New Long Pond 67 Fresh Pond 62 Pinewood Lake 51 Gallow's Pond 22 Rocky Pond 419 Great Herring Pond (4)(6) 48 Russell Mill Pond (5) 84 Great Island Pond (3) (4) 20 Shallow Pond 290 Great South Pond (4) 14 Ship Pond (6) 29 Gunner's Exchange Pond (6) 20 South Triangle Pond 229 Halfway Pond (4)(6) 15 Three-Cornered Pond 30 Hedge's Pond 91 West Ponds (4) 22 Hoyt Pond 37 White's Pond 12 Indian Brook Reservoir 26 Widgeon Pond 14 Island Pond (North) (1) Highlighted ponds are 30 acres or less – Prohibited to internal combustion engines. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Fifty-Sixth Annual Report of the Trustees of Public Reservations 1946

19'iG Acquisition Courtesy A. Palme BARTHOLOMEWS COBBLE, SHEFFIELD The Trustees of Public Reservations VOLUNTARILY SUPPORTED PRIVATELY ADMINISTERED A Trust to Preserve for Public Enjoyment Beautiful and Historic Places in Massachusetts FIFTY-SIXTH Annual Report 1946 LIST OF CONTENTS ON LAST PAGE THE TRUSTEES OF PUBLIC RESERVATIONS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES STANDING COMMITTEE Robert Walcott, Cambridge {President) Henry M. Changing, Sherborn {Vice President) Charles S. Bird, East Walpole {Chairman) Fraxcis E. Frothixgham, Cambridge William Ellery, Boston William Roger Greeley, Lexington Charles S. Pierce, Milton Fletcher Steele, Boston William P. Wharton, Groton COMMITTEE ON RESERVATIONS Fletcher Steele {Chairman) Miss Amelia Peabody Laurexce B. Fletcher, ex officio COMMITTEE ON FINANCE Fraxcis E. Frothingham {Chairman) Allan Forbes Robert E. Goodwix Charles S. Pierce Charles S. Bird Council Member of the National Trust of England Representing The Trustees of Public Reservations Allax Forbes, Treasurer State Street Trust Co. Boston 9, Massachusetts Laurexce B. Fletcher, Secretary office of the trustees 50 Congress Street Boston 9, Massachusetts / BARTHOLOMEW'S COBBLE, SHEFFIELD A cobble, as Berkshire people use the word, means a rock island in the alluvial meadow land of the valley. As our valley is underlaid with limestone, our cobbles are limestone and hence the haunts of lime-loving ferns and rock plants. The largest cobble in Sheffield, long a picnic site for the region, is Bartholo- mew's Cobble now owned by The Trustees of Public Reservations secured by public subscription and with the aid of the Founders Fund of the Garden Club of America. Its east face plunges directly down to the Housatonic River. On the west it tapers into fields which lead to the massive wall of the Taconic range. -

314 Cmr 4.00: Massachusetts Surface Water Quality Standards

Disclaimer The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) provides this file for download from its Web site for the convenience of users only. Please be aware that the OFFICIAL versions of all state statutes and regulations (and many of the MassDEP policies) are only available through the State Bookstore or from the Secretary of State’s Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR) Subscription Service. When downloading regulations and policies from the MassDEP Web site, the copy you receive may be different from the official version for a number of reasons, including but not limited to: • The download may have gone wrong and you may have lost important information. • The document may not print well given your specific software/ hardware setup. • If you translate our documents to another word processing program, it may miss/skip/lose important information. • The file on this Web site may be out-of-date (as hard as we try to keep everything current). If you must know that the version you have is correct and up-to-date, then purchase the document through the state bookstore, the subscription service, and/or contact the appropriate MassDEP program. 314 CMR: DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 314 CMR 4.00: MASSACHUSETTS SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS Section 4.01: General Provisions 4.02: Definitions 4.03: Application of Standards 4.04: Antidegradation Provisions 4.05: Classes and Criteria 4.06: Basin Classification and Maps 4.01: General Provisions (1) Title. 314 CMR 4.00 shall be known as the "Massachusetts Surface Water Quality Standards". (2) Organization of the Standards. 314 CMR 4.00 is comprised of six sections, General Provisions (314 CMR 4.01) Definitions (314 CMR 4.02), Application of Standards (314 CMR 4.03), Antidegradation Provisions (314 CMR 4.04), Classes and Criteria (314 CMR 4.05), and Basin Classification and Maps (314 CMR 4.06). -

Streamflow, Ground-Water Recharge and Discharge, and Characteristics of Surficial Deposits in Buzzards Bay Basin, Southeastern Massachusetts U.S

Streamflow, Ground-Water Recharge and Discharge, and Characteristics of Surficial Deposits in Buzzards Bay Basin, Southeastern Massachusetts U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4234 Prepared in cooperation with MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT, DIVISION OF RESOURCE CONSERVATION, OFFICE OF WATER RESOURCES Streamflow, Ground-Water Recharge and Discharge, and Characteristics of Surficial Deposits in Buzzards Bay Basin, Southeastern Massachusetts By GARDNER C. BENT U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4234 Prepared in cooperation with MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT, DIVISION OF RESOURCE CONSERVATION, OFFICE OF WATER RESOURCES Marlborough, Massachusetts 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Chief, Massachusetts-Rhode Island District U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center Water Resources Division Open-File Reports Section 28 Lord Road, Suite 280 Box 25286, MS 517 Marlborough, MA 01752 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Plymouth Open Space Trail Guide

SCAN QR CODE TO ACCESS MAPS ON YOUR PHONE Welcome to the Walking Trails of Plymouth! Pictured is Center Hill Preserve Special Thanks and Acknowledgements Printing of these trail guides was generously sponsored by SHP Financial, Southeastern Massachusetts Pine Barrens Alliance (SEMPBA), Betsy Hall and Phil Leddy. Thank you to David Gould and Plymouth’s Department of Marine & Environmental Affairs and Patrick Farah for their valuable contributions. The artwork throughout the book was drawn by artist Heidi Mayo, and provided by SEMPBA. Trail descriptions written by Diane Griffiths Peck amended from the Take a Hike column in the Old Colony Memorial. Guide compiled by Andrea Dickinson in collaboration with the Open Space Committee. REDUCE WASTE BY PASSING THIS GUIDE ON TO OTHERS TABLE OF CONTENTS About Plymouth Open Space 1 Massachusetts Coastal Pine Barrens 2 Overview Map 3 Beaver Dam Conservation Area 5 Black Cat Preserve 7 Center Hill Preserve 9 Clear Pond Preserve 11 Crawley Woodlands Preserve 13 David E. Alper Preserve 15 Dixon Preserve at Hio Hill 17 Eel River Preserve 19 Hedges Pond Recreational Area & Preserve 21 Morton Park 23 Russell Mill Pond 25 Russell Sawmill Pond Conservation Area 27 Town Brook & Patuxet Preserve 29 Town Forest Conservation Area 31 Wheel Friendly Trails 33 Trails Under Construction 35 Tips for Reducing Litter 36 ABOUT PLYMOUTH OPEN SPACE As the largest municipality in Massachusetts by area, Plymouth currently has approximately 28% of our 65,000 acres designated as protected open space. Plymouth contains the third highest per square mile occurrence of rare, threatened and endangered species of any community in Massachusetts, 36 miles of coastline and 365+ inland ponds including 32 globally rare coastal plain ponds. -

John and Priscilla Alden Family Sites

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ALDEN, JOHN AND PRISCILLA, FAMILY SITES Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Alden, John and Priscilla, Family Sites Other Name/Site Number: Alden House (DUX.38) and Original Alden Homestead Site (aka Alden I Site, DUX-HA-3) 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 105 Alden Street Not for publication: City/Town: Duxbury Vicinity: State: Massachusetts County: Plymouth Code: 023 Zip Code: 02331 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X Public-Local: X District: __ Public-State: Site: _X Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 3 buildings 1 sites structures _ 1 objects 2 4 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Original Alden Homestead NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ALDEN, JOHN AND PRISCILLA, FAMILY SITES Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Top Things to Do in Plymouth" a City That Has Earned the Epithet for Being 'America's Hometown', Plymouth's History Can Be Traced Back to the Era of the Pilgrims

"Top Things To Do in Plymouth" A city that has earned the epithet for being 'America's Hometown', Plymouth's history can be traced back to the era of the Pilgrims. A city steeped in culture, Plymouth is an open book waiting to enlighten visitors through its museums and many historic sights. Realizzata per : Cityseeker 10 Posizioni indicati Plymouth Rock "Homage to the Plymouth Pilgrims" An English ship, Mayflower, brought with it over 100 pilgrims who landed on the harbor of Plymouth and discovered their newfound freedom in the year 1620. The Plymouth Rock is supposedly the exact spot of the landing of the pilgrims and today a major portion of it is sheltered under a grand canopy made of granite. Located within the Pilgrim Memorial State Park, by NYC1887 the rock is one of the major attractions for tourists visiting Massachusetts and with guided tours, people get to learn about the English pilgrims and their heritage. +1 508 747 7525 (Tourist Information) www.seeplymouth.com/things-to- 79 Water Street, Pilgrim Memorial State do/plymouth-rock Park, Plymouth MA Pilgrim Hall Museum "A nation's roots" The Plymouth colony, which lasted from 1620-1692, is firmly embedded in the collective imagination as one of the major chapters in the historic story of the United States. This museum reveals some of the earliest pages in that story, through artifacts both famous (William Bradford's Bible) and humble (household artifacts). It also acknowledges the other by Giorgio Galeotti and often overlooked, characters in the story: the native Americans who had settled these shores many centuries before Europeans came sailing in on the Mayflower. -

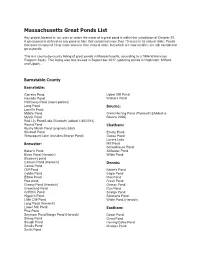

Open PDF File, 163.51 KB, for Massachusetts Great Ponds List

Massachusetts Great Ponds List Any project located in, on, over or under the water of a great pond is within the jurisdiction of Chapter 91. A great pond is defined as any pond or lake that contained more than 10 acres in its natural state. Ponds that once measured 10 or more acres in their natural state, but which are now smaller, are still considered great ponds. This is a county-by-county listing of great ponds in Massachusetts, according to a 1996 Waterways Program Study. This listing was last revised in September 2017 (updating ponds in Hopkinton, Milford, and Upton). Barnstable County Barnstable: Garretts Pond Upper Mill Pond Hamblin Pond Walkers Pond Hathaway Pond (lower portion) Long Pond Bourne: Lovell's Pond Middle Pond Great Herring Pond (Plymouth) [Added to Mystic Pond Bourne 2006] Red Lily Pond/Lake Elizabeth (added 1/30/2014) Round Pond Chatham: Rushy Marsh Pond (originally tidal) Shubael Pond Emery Pond Wequaquet Lake (includes Bearse Pond) Goose Pond Lovers Lake Brewster: Mill Pond Schoolhouse Pond Baker's Pond Stillwater Pond Black Pond (Harwich) White Pond Blueberry pond Cahoon Pond (Harwich) Dennis: Canoe Pond Cliff Pond Baker's Pond Cobbs Pond Eagle Pond Elbow Pond Flax Pond Flax pond Fresh Pond Grassy Pond (Harwich) Grassy Pond Greenland Pond Run Pond Griffith's Pond Scargo Pond Higgin's Pond Simmons Pond Little Cliff Pond White Pond (Harwich) Long Pond (Harwich) Lower Mill Pond Eastham: Pine Pond Seymour Pond/Bangs Pond (Harwich) Depot Pond Sheep Pond Great Pond Slough Pond Herring/Coles Pond Smalls Pond Minister -

Section 2. Blue Hills Reservation

View of Great Blue Hill from across Ponkapoag Pond. (See Appendix K for photo information.) SECTION 2. BLUE HILLS RESERVATION 2.1. INTRODUCTION well over one-hundred archaeological and historic resources that tell the story of the Blue Hills, from The Blue Hills Reservation (Blue Hills) is located its native peoples to its role in Cold War era missile approximately eight miles south of downtown defense. One resource, the Blue Hills Meteorological Boston, at the intersection of Interstate 93 and Route Observatory, is a National Historic Landmark. 24. (Figure 2.1.1) It was one of the first reservations established by the Metropolitan Park Commission The Reservation’s physical, political, and regulatory (MPC). Since its creation in 1893, the Blue Hills has attributes are summarized in Table 2.1.1. been the largest protected open space in Associated Properties. The Blue Hills’ previous metropolitan Boston. RMP (DCR 2011a) included two properties not in The Reservation is perhaps best known for its this section: Town Brook Flood Control Site and recreation facilities and activities. It has an extensive Ponkapoag Golf Course. Town Brook Flood Control trails system that is well-used by the region’s hikers Site was never part of the Blue Hills Reservation; and mountain bikers, and a guarded beach for public but was included in the 2011 RMP due to its swimming. The park is also home to one of three proximity to the Reservation. Information on this downhill ski areas in Massachusetts’ park system. property is provided in Section 1. Ponkapoag Golf There are also multiple athletic fields and ice rinks. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or Country -- America -- North America -- United States -- Northe

G3701.S UNITED STATES. HISTORY G3701.S .S1 General .S12 Discovery and exploration Including exploration of the West .S2 Colonial period .S26 French and Indian War, 1755-1763 .S3 Revolution, 1775-1783 .S4 1783-1865 .S42 War of 1812 .S44 Mexican War, 1845-1848 .S5 Civil War, 1861-1865 .S55 1865-1900 .S57 Spanish American War, 1898 .S6 1900-1945 .S65 World War I .S7 World War II .S73 1945- 88 G3702 UNITED STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G3702 ETC. .C6 Coasts .G7 Great River Road .L5 Lincoln Highway .M6 Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail. Mormon Trail .N6 North Country National Scenic Trail .U5 United States Highway 30 .U53 United States Highway 50 .U55 United States Highway 66 89 G3707 EASTERN UNITED STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3707 FEATURES, ETC. .A5 Appalachian Basin .A6 Appalachian Mountains .I4 Interstate 64 .I5 Interstate 75 .I7 Interstate 77 .I8 Interstate 81 .J6 John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail .N4 New Madrid Seismic Zone .O5 Ohio River .U5 United States Highway 150 .W3 Warrior Trail 90 G3709.32 ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3709.32 FEATURES, ETC. .A6 Appalachian Trail .A8 Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway .C6 Coasts .I5 Interstate 95 .O2 Ocean Hiway .P5 Piedmont Region .U5 United States Highway 1 .U6 United States Highway 13 91 G3712 NORTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3712 FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Coasts .C8 Cumberland Road .U5 United States Highway 22 92 G3717 NORTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3717 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Coasts .T3 Taconic Range .U5 United States Highway 202 93 G3722 NEW ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G3722 ETC. .C6 Coasts .C62 Connecticut River 94 G3732 MAINE.