Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

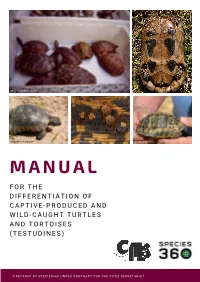

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Factors Influencing the Occurrence and Vulnerability of the Travancore Tortoise Indotestudo Travancorica in Protected Areas in South India

Factors influencing the occurrence and vulnerability of the Travancore tortoise Indotestudo travancorica in protected areas in south India V. DEEPAK and K ARTHIKEYAN V ASUDEVAN Abstract Protected areas in developing tropical countries under pressure from high human population density are under pressure from local demand for resources, and (Cincotta et al., 2000), with enclaves inhabited by margin- therefore it is essential to monitor rare species and prevent alized communities that traditionally depend on forest overexploitation of resources. The Travancore tortoise resources for their livelihoods (Anand et al., 2010). Indotestudo travancorica is endemic to the Western Ghats The Travancore tortoise Indotestudo travancorica is in southern India, where it inhabits deciduous and evergreen endemic to the Western Ghats. It inhabits evergreen, semi- forests. We used multiple-season models to estimate site evergreen, moist deciduous and bamboo forests and rubber occupancy and detection probability for the tortoise in two and teak plantations (Deepaketal., 2011).The species occursin protected areas, and investigated factors influencing this. riparian patches and marshes and has a home range of 5.2–34 During 2006–2009 we surveyed 25 trails in four forest ha (Deepak et al., 2011). Its diet consists of grasses, herbs, fruits, types and estimated that the tortoise occupied 41–97%of crabs, insects and molluscs, with occasional scavenging on the habitat. Tortoise presence on the trails was confirmed by dead animals (Deepak & Vasudevan, 2012). It is categorized as sightings of 39 tortoises and 61 instances of indirect evidence Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and listed in Appendix II of of tortoises. There was considerable interannual variation CITES (Asian Turtle Trade Working Group, 2000). -

A Sulcata Here, a Sulcata There, a Sulcata Everywhere Text and Photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter

A Sulcata Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) emerging from a burrow in its enclosure. of the African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) A Sulcata Here, A Sulcata There, A Sulcata Everywhere text and photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter n 1986 my wife and I fell in The breeder said to feed them pumpkin All the stucco along the side of the house love with the Sulcata Tor- and alfalfa. There was not a lot of diet infor- as far as they could ram was broken. The toise and decided to purchase mation available then. We did not have good male more than the female did the greater a pair. Yes, purchase. Twenty-three years luck with the breeder’s diet. They preferred damage. Our youngest son had the outside ago there were not many Sulcatas available. the Bermuda grass, rose petals and hibis- corner bedroom upstairs, every night after We found a “BREEDER” in Riverside, CA. cus flowers in the back yard. We gave them he would go to bed I could here him holler- Made the contact and brought the pair home other treats once in a while: apples, squash, ing at that %#@* turtle. The Sulcata would toI Ventura, CA. So began an adventure that and other vegetables. Pumpkin never was start ramming the side of the house. I would we still enjoy today. high on their list of treats! They also loved to go down and move him, put things in his We were told they were about seven years drink from a running hose laid on the lawn. -

Descriptions of Some A.Frican Tortoises

A"nals aftlte Natal Museum. Vol. VI, 1)(1ft 3 DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME AFRICAN TORTOISES. 46 1 Descriptions of some A.frican Tortoises. By John II C\\'itt. With P lates XXXVI-XXXVIII, and 5 Text. fi gul·es. CONTENTS. P elusios s inuatus s inu n.t us Smith J(j2 P elus ios s illu atus zuluensis H elQift 462 P ell1si os ni g r ica. ns n igricnns DonllC/. 4(\3 Pelus ios ni g ri can s castanoides SIIUS)1. n . 4(13 Peil1si os nigr icn.ns ca.stan e us Schw. 464 P elus ios nigricans rh odesianus H ellJi tt 465 Kinixys hellian!} Gray -I n? Kinixys nogll ey i Lataste ·HiS Kin ixys s pekii Gray. 469 Kinixys be lliana. zombensis sllbsp. '11. ·WO Kinixys belJin.nn. zulllon sis subs)1 . n. 47 1 Kinixys n. ustra lis 8p. It. 477 Kinixys da.rlingi Blgr. 4, 1 Kini xys jordn.ni sp . n . 482 Kinixys yonn gi ap. n. 4SG Kini xys lo bn.ts ia na Pou'er 488 H omopus WaMb. ..HHi Pseudomopus g. n . ·Hlli T estlld o L . 4!)H Neotestlldo g. n. 50" 462 JOHN HEWI'IT. THE material dealt wi th in this revi ew has bef' 1l derived from varioll s sources. A good portion of it is contained in the Albany Musemu, and for the loan of specimens I am especia.lly indebted to the Mu seums at Pretoria, Kimberley and Pietermaritzburg. It, may be .aid that the. present study again illustrates the fact t.hat the closer a group of organisms is studied and the wider the area from which they are obt.ained, the greater is the difficnlty ill formulating any clear diagnosis of specific characters. -

Growing and Shrinking in the Smallest Tortoise, Homopus Signatus Signatus: the Importance of Rain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Oecologia (2007) 153:479–488 DOI 10.1007/s00442-007-0738-7 GLOBAL CHANGE AND CONSERVATION ECOLOGY Growing and shrinking in the smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus: the importance of rain Victor J. T. Loehr · Margaretha D. Hofmeyr · Brian T. Henen Received: 21 November 2006 / Accepted: 21 March 2007 / Published online: 24 April 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Climate change models predict that the range of dorso-ventrally, so a reduction in internal matter due to the world’s smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus, starvation or dehydration may have caused SH to shrink. will aridify and contract in the next decades. To evaluate Because the length and width of the shell seem more rigid, the eVects of annual variation in rainfall on the growth of reversible bone resorption may have contributed to shrink- H. s. signatus, we recorded annual growth rates of wild age, particularly of the shell width and plastron length. individuals from spring 2000 to spring 2004. Juveniles Based on growth rates for all years, female H. s. signatus grew faster than did adults, and females grew faster than need 11–12 years to mature, approximately twice as long as did males. Growth correlated strongly with the amount of would be expected allometrically for such a small species. rain that fell during the time just before and within the However, if aridiWcation lowers average growth rates to the growth periods. Growth rates were lowest in 2002–2003, level of 2002–2003, females would require 30 years to when almost no rain fell between September 2002 and mature. -

A Survey of the Potential Distribution of the Threatened Tortoise Centrochelys Sulcata Populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa)

Tropical Ecology 57(4): 709-716, 2016 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com A survey of the potential distribution of the threatened tortoise Centrochelys sulcata populations in Burkina Faso (West Africa) FABIO PETROZZI1,2, EMMANUEL M. HEMA3,4 , LUCA LUISELLI1,5*& WENDENGOUDI GUENDA3 1Niger Delta Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation Unit, Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 5080 Nkpolu, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria 2Ecologia Applicata Italia s.r.l., via Edoardo Jenner 70, Rome, Italy 3Université de Ouagadougou/CUPD, Laboratoire de Biologie et Ecologie Animales, 09 B.P. 848 Ouagadougou 09 - Burkina Faso 4Groupe des Expert en Gestion des Eléphants et de la Biodiversité de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (GEGEBAO) 5Institute for Development, Ecology, Conservation and Cooperation, via G. Tomasi di Lampedusa 33, I-00144 Rome, Italy Abstract: The African spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata) is a threatened species, especially in West Africa, where it shows a scattered distribution. In Burkina Faso, the species distribution is unknown and we documented the current distribution and potential habitat characteristics. We found evidence of the species in a few sites in the northern and eastern part of the country, whereas some records from the southern part of Burkina Faso were considered unreliable. Multiple specimens were recorded only in four localities, mainly in the Sahel ecological zone. Annual rainfall was negatively related to the observed number of tortoises per site, and indeed these tortoises were found in the Sahel and adjacent ecoregions where rainfall is lower than other regions in Burkina Faso whereas latitude and numbers of tortoise individuals observed in each site were positively related. -

The Internet Based Trade in Madagascar's Critically Endangered

THE INTERNET BASED TRADE IN MADAGASCAR’S CRITICALLY ENDANGERED TORTOISE SPECIES: A PRELIMINARY STUDY IDENTIFYING THE CONSERVATION THREATS Ryan C.J. Walker1, 2 1Nautilus Ecology, 1 Pond Lane, Greetham, Rutland, LE15 7NW, UK 2Department of Life Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK Email: [email protected] Introduction Wildlife trade is an issue fundamental to global biodiversity conservation. Directly and indirectly, this trade is increasing demand and consumption on natural resources at an alarming rate (Broad et al., 2003). Reptiles are thought to make up about 43% of the trade (Alacs & Georges, 2008), representing one of the largest taxa groups (Reeve, 2002). Madagascar’s four Critically Endangered (IUCN, 2009) tortoise species, the spider tortoise Pyxis arachnoides (Fig. 1a), flat tailed tortoise Pyxis planicauda, radiated tortoise Astrochelys radiata (Fig. 1b) and the ploughshare tortoise Astrochelys yniphora, have suffered considerable conservation pressures in recent years from both habitat destruction (Walker et al., 2004; Pedrono, 2008) and suspected pressure from illegal collection and export to support the pet trade (O’Brien et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2004). Since 2004 legal commercial trade in all four species has been restricted as a result of their Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix I status. In addition to this all four species are protected under Malagasy national law (Pedrono, 2008). Despite this A. radiata has consistently been one of the most widely traded species of tortoise within the pet markets of south-east Asia in recent years (Nijman & Shepherd, 2007). Currently the internet provides a convenient and powerful medium for both legal and illegal wildlife traders to advertise and sell their wares, often anonymously (Wu, 2007; Alacs & Georges, 2008). -

(Manouria Emys) and a Malaysian Giant Turtle

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSIRCF REPTILES • VOL15, &NO AMPHIBIANS 4 • DEC 2008 189 • 27(1):89–90 • APR 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Only. Chasing in Bullsnakes Captivity? (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: An Interaction between On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 Two Threatened. The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis Chelonians,) and Humans on Grenada: an Asian Giant A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 TortoiseRESEARCH ARTICLES (Manouria emys) and a Malaysian . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida Giant ............................................. TurtleBrian J. Camposano, Kenneth (Orlitia L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellenborneensis M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky )212 CONSERVATION ALERT Matthew Mo . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . More Than MammalsP.O. ...............................................................................................................................Box -

Investigating the Thermal Biology and Behaviour of Captive Radiated Tortoises

MedDocs Publishers ISSN: 2639-4391 Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences Open Access | Research Article Investigating the Thermal Biology and Behaviour of Captive Radiated Tortoises Avraham Terespolsky; James Edward Brereton* University Centre Sparsholt, England *Corresponding Author(s): James Edward Brereton Abstract University Centre Sparsholt, Westley Lane, Sparsholt, Thermoregulation is integral to the maintenance of rep- Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF, England. tile biological function and health, and therefore is a key Email: [email protected] area of investigation for herpetologists. To investigate the relationship between core body temperature and behav- iour, a behavioural study was conducted in which iButton data loggers were placed on a group of captive radiated tor- Received: Nov 09, 2020 toises (Astrochelys radiata) located at Sparsholt College’s Accepted: Jan 04, 2021 Animal Management Centre, in Hampshire, UK. Correla- tions between core body temperature and specific behav- Published Online: Jan 08, 2021 iours were covered. Body mass had a significant effect on Journal: Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences average core body temperature (P= <0.0001) with higher Publisher: MedDocs Publishers LLC average temperatures recorded in larger individuals over Online edition: http://meddocsonline.org/ longer periods. There was a significant positive relationship between mean body temperature and basking behaviour, Copyright: © Brereton JE (2021). This Article is (P= 0.001, r= 0.485), and a negative correlation between distributed under the terms of Creative Commons mean body temperature and feeding (P= 0.006, r= -0.155). Attribution 4.0 International License Temperature did not significantly affect the prevalence of any other behaviours, though a trend toward greater ex- pression of social behaviour, and fewer bouts of aggressive ramming, was observed when tortoises achieved higher body temperatures.