Small Places Like St Helena Have Big Questions to Ask’: the Inaugural Lecture of a Professor of Island Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 2016 Ianohio.Com

AUGUST 2016 AUGUSTianohio.com 2016 ianohio.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com AUGUST 2016 word “brask- By the begin- er,” meaning ning of the 20th “a dangerous century, howev- place.” er, the islanders The Great knew their way Blasket Island of life was com- is the largest ing to an end. of the island Some decided to The Blasket Islands group. We know that Christian monks write down their The Blasket Islands are a group of islands inhabited the island at a very early time. memories to pre- approximately 3 miles off the southwest A recently-discovered document records serve them, like coast of the Dingle Peninsula in County people living on the island as early as 1597. Peig Sayers (An Kerry. The islands in the group are: The number of people living on the Island Old Woman’s Re- The Great Blasket Island (An Blascaod has ebbed and flowed over the centuries. flections), Muiris Mhór – ahn blas-ked vor – Great Blasket), There was a population of about 150 living Ó Súilleabháin Beginish (Beiginis – beg-inish – small there in 1840, but after the Great Famine (Twenty Years A’ island), that had decreased to 100. The population Growing), Mi- Inishnabro (Inis na Bró – inish-na-bro – is said to have reached its peak in 1916, at cheál O’Guiheen (A Pity Youth Does Not were abandoned and fell into ruin. Little at- island of the millstone), 176. From then on it was in decline, due to Last), and Tomás O’Crohan (The Islandman). tempt was made to preserve the life they had Inishvickillane (Inis Mhic Uileáin – inish- death and immigration to America. -

Fear and Money in Dubai

metropolitan disorders The hectic pace of capitalist development over the past decades has taken tangible form in the transformation of the world’s cities: the epic expansion of coastal China, deindustrialization and suburbanization of the imperial heartlands, massive growth of slums. From Shanghai to São Paolo, Jerusalem to Kinshasa, cityscapes have been destroyed and remade—vertically: the soar- ing towers of finance capital’s dominance—and horizontally: the sprawling shanty-towns that shelter a vast new informal proletariat, and McMansions of a sunbelt middle class. The run-down public housing and infrastuctural projects of state-developmentalism stand as relics from another age. Against this backdrop, the field of urban studies has become one of the most dynamic areas of the social sciences, inspiring innovative contributions from the surrounding disciplines of architecture, anthropology, economics. Yet in comparison to the classic accounts of manufacturing Manchester, Second Empire Paris or Reaganite Los Angeles, much of this work is strikingly depoliticized. Characteristically, city spaces are studied in abstraction from their national contexts. The wielders of economic power and social coercion remain anonymous. The broader political narrative of a city’s metamorphosis goes untold. There are, of course, notable counter-examples. With this issue, NLR begins a series of city case studies, focusing on particular outcomes of capitalist globalization through the lens of urban change. We begin with Mike Davis’s portrait of Dubai—an extreme concentration of petrodollar wealth and Arab- world contradiction. Future issues will carry reports from Brazil, South Africa, India, gang-torn Central America, old and new Europe, Bush-era America and the vertiginous Far East. -

CHAPTER 7 the Fint Journeys Across the Catibbean Sea Were Made By

CHAPTER 7 few chosen ground operaton. Those who have failed to book can take rlleir chances and get a cheaper deal with tati-drivers. The most popular ports of call are the ones with the hcst duty-free shopping and casinos. The shops arc ice-cold and could be on Fifth avenue: the gifts, under glass, arc much the same whether in Ocho Rios oI Antigua - jewellery, perfumes, china iigmincs of pastel-coloured cottages, milk maids or puppies. Each destination, however, is in conlpetition with the next fo provide a shoppen’ parad&. St Kim, for suample, with its modest duty-free mall in Basseterre, must try to conlpere with St Marten, its flashy Americanized neighbour, stiff with shops and casinos. ‘We would like to see a greater turnover so we are The fint journeys across the Catibbean Sea were made by Amerindian upgrading our duty-free outlets,’ says Hilary Wattlry, the marketing canoeists who settled the island chains, paddling north from the river manager for St Kim Division of Tourism. Or Grenada, where there is systems of the Orinoco and the Amazon. Hundreds of years later the lit& to buy and only the charm of% George’s to attract the tourists. ‘We Spanish explorers arrived, and when other European powers joined the need more and fancier shopping. There arc not enough attractions and fight for control of the Caribbean it was the sea, not the land, which saw shops for the cruise peoplr,’ says Andrew Bierzynski, a charter boat their greatest battles. Then the sea became an economic highway: for operaror. -

Blasket Islands SAC (Site Code: 2172)

NPWS Blasket Islands SAC (site code: 2172) Conservation objectives supporting document - Marine Habitats and Species Version 1 February 2014 Introduction Blasket Islands SAC is designated for the marine Annex I qualifying interest of Reefs and Submerged or partially submerged sea caves (Figure 1 and 2) and the Annex II species Phoca vitulina (harbour porpoise) and Halichoerus grypus (grey seal). A BioMar survey of this site was carried out in 1996 (Picton and Costello, 1997) and a subtidal reef survey was undertaken in 2010 (Aquafact, 2010); InfoMar (Ireland’s national marine mapping programme) data from the site was also reviewed. These data were used to determine the physical and biological nature of the Annex I reef habitat. The distribution and ecology of intertidal or subtidal seacaves has not previously been the subject of scientific investigation in Ireland and the extents of very few individual caves have been mapped in detail. Analysis of the imagery from the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources coastal oblique aerial survey yielded some information concerning the expected location of partly submerged seacaves in Blasket Islands SAC (Figure 2). There is no additional information available concerning the likely distribution of permanently submerged seacaves in the site at present. Whilst surveys undertaken in the UK indicate the structure and functions of seacaves are largely influenced by hydrodynamic forces and water quality, no such information is yet available for Ireland. A considerable number of records of harbour porpoise have been gathered within this site and adjacent waters off the south-west coast of Ireland, particularly over the last two decades (e.g. -

15 Private Island Escapes

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For non-personal use, please contact us at 1-866-831-4314 or email [email protected]. INSIDE — NEW DISCOVERIES IN SOUTHERN FRANCE + FAVORITE PRIVATE ISLANDS WORLDWIDE ANDREW HARPER’S SEPTEMBER 2020 SINCE 1979 Traveling the world in search of truly enchanting places Pool at Le Vieux Castillon, Castillon-du-Gard Languedoc-Roussillon Revisited Rolling vineyards, exquisite villages, Roman ruins, open-air markets, profound tranquility he high-speed train from Paris the Cévennes mountains to the north True, visitors flock to Nîmes (pop. usually takes just under four and the Mediterranean to the south, 150,000), an ancient and atmospheric city T hours to reach Avignon, the Gard offers much of what American of great charm, as well as to Uzès, one of gateway to Provence. On leaving the city, travelers love about Provence but with France’s most beautiful towns, and to the most travelers drive southeast into the the added allure of being an unspoiled first-century Pont du Gard, the highest Vaucluse. However, if you cross to the and uncrowded area, where the traffic and most dramatic of Roman aqueduct west bank of the Rhône River, you enter on the plane tree-shaded back roads bridges. But much of Gard remains a the department of Gard in the region usually amounts to little more than a serene, village-dotted landscape planted of Languedoc-Roussillon. Bounded by tractor or two. with orchards and vineyards. -

Blasket Islands SAC (Site Code: 2172)

NPWS Blasket Islands SAC (site code: 2172) Conservation objectives supporting document- European Dry Heaths Version 1 March 2014 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Blasket Islands SAC .................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Conservation objectives ........................................................................................................... 2 2. Habitat area................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Habitat distribution ....................................................................................................................... 3 4. Structure and functions ................................................................................................................. 3 4.1 Ecosystem function: soil nutrient status ................................................................................... 3 4.2 Vegetation structure: positive indicator species ....................................................................... 4 4.3 Vegetation structure: growth phases of ling ............................................................................. 5 4.4 Vegetation structure: signs of browsing ................................................................................... 5 4.5 Vegetation structure: native trees and -

Embrace the Wild Atlantic Way of Life

SOUTHERN PENINSULAS & HAVEN COAST WildAtlanticWay.com #WildAtlanticWay WELCOME TO THE SOUTHERN PENINSULAS & HAVEN COAST The Wild Atlantic Way, the longest defined coastal touring route in the world stretching 2,500km from Inishowen in Donegal to Kinsale in West Cork, leads you through one of the world’s most dramatic landscapes. A frontier on the very edge of Europe, the Wild Atlantic Way is a place like no other, which in turn has given its people a unique outlook on life. Here you can immerse yourself in a different way of living. Here you can let your freer, spontaneous side breathe. Here you can embrace the Wild Atlantic Way of Life. The most memorable holidays always have a touch of wildness about them, and the Wild Atlantic Way will not disappoint. With opportunities to view the raw, rugged beauty of the highest sea cliffs in Europe; experience Northern Lights dancing in winter skies; journey by boat to many of the wonderful islands off our island; experience the coast on horseback; or take a splash and enjoy the many watersports available. Stop often at the many small villages and towns along the route. Every few miles there are places to stretch your legs and have a bite to eat, so be sure to allow enough time take it all in. For the foodies, you can indulge in some seaweed foraging with a local guide with a culinary experience so you can taste the fruits of your labours. As night falls enjoy the craic at traditional music sessions and even try a few steps of an Irish jig! It’s out on these western extremities – drawn in by the constant rhythm of the ocean’s roar and the consistent warmth of the people – that you’ll find the Ireland you have always imagined. -

79667 FCCA Profiles

TableTable ofofContentsContents CARNIVAL CORPORATION Mark M. Kammerer, V.P., Worldwide Cruise Marketing . .43 Micky Arison, Chairman & CEO (FCCA Chairman) . .14 Stein Kruse, Senior V.P., Fleet Operations . .43 Giora Israel, V.P., Strategic Planning . .14 A. Kirk Lanterman, Chairman & CEO . .43 Francisco Nolla, V.P., Port Development . .15 Gregory J. MacGarva, Director, Procurement . .44 Matthew T. Sams, V.P., Caribbean Relations . .44 CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES Roger Blum, V.P., Cruise Programming . .15 NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE Gordon Buck, Director, Port Operations. .16 Capt. Kaare Bakke, V.P. of Port Operations . .48 Amilicar “Mico” Cascais, Director, Tour Operations . .16 Sharon Dammar, Purchasing Manager, Food & Beverages . .48 Brendan Corrigan, Senior V.P., Cruise Operations . .16 Alvin Dennis, V.P., Purchasing & Logistics Bob Dickinson, President . .16 (FCCA Purchasing Committee Chairman) . .48 Vicki L. Freed, Senior V.P. of Sales & Marketing . .17 Colin Murphy, V.P, Land & Air Services . .48 Joe Lavi, Staff V.P. of Purchasing . .18 Joanne Salzedo, Manager, International Shore Programs . .49 David Mizer, V.P., Strategic Sourcing Global Source . .18 Andrew Stuart, Senior V.P., Marketing & Sales . .49 Francesco Morrello, Director, Port Development Group . .18 Colin Veitch, President & CEO . .49 Gardiner Nealon, Manager, Port Logistics . .19 Mary Sloan, Director, Risk Management . .19 PRINCESS CRUISES Terry L. Thornton, V.P., Marketing Planning Deanna Austin, V.P., Yield Management . .52 (FCCA Marketing Committee Chairman) . .19 Dean Brown, Executive V.P., Customer Service Capt. Domenico Tringale, V.P., Marine & Port Operations . .19 & Sales; Chairman & CEO of Princess Tours . .52 Jeffrey Danis, V.P., Global Purchasing & Logistics . .52 CELEBRITY CRUISES Graham Davis, Manager, Shore Operations, Caribbean and Atlantic . -

Pim-17-Digital.Pdf

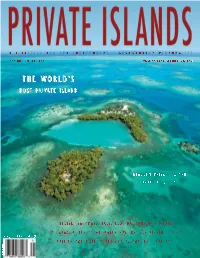

A L I F E S T Y L E F O R T H E I N D E P E N D E N T - A D V E N T U R O U S P E R S O N A L I T Y S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 0 1 7 W W W . P R I V A T E I S L A N D S M A G . C O M T H E WO R L D ’ S M O S T P R I VAT E I S L A N D G L A D D E N P R I VAT E I S L A N D B A R R I E R R E E F, B E L I Z E F I V E B A H A M I A N C R O W N J E W E L S B E L I Z E , B A H A M A S , I T A L Y , F L O R I D A , S A N J U A N I S L A N D S , N I C A R A G U A , T A H I T I , G E O R G I A N B A Y , B R I T I S H V I R G I N I S L A N D S , CAD $14.95 1 U.S. -

This Residential Resort for Billionaires on Hawaii Island Will Amaze You

/ Lifestyle / #DeLuxe MAY 1, 2018 @ 10:02 AM 1,479 2 Free Issues of Forbes This Residential Resort For Billionaires On Hawaii Island Will Amaze You Carrie Coolidge , CONTRIBUTOR FULL BIO Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own. Courtesy of Four Seasons Resort Hualalai The Palm Grove swimming pool at the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai. One of Earl “Uncle Earl” Regidor’s unofficial duties as Ka`upulehu Cultural Center Manager at the Four Seasons Resort Hualālai is performing a blessing at home sites before ground is broken. Home buyers at the sprawling luxury residential development that surrounds the Four Seasons Resort Hualālai often invite Uncle Earl to perform the ancient blessing to consecrate the land---once the site of an ancient fishing village---before building a new home. The blessing, which is attended by the homeowner’s family and their contractor, consecrates the land out of respect for the Hawaiian people who lived there for centuries before them. “I do the blessing for the sake of asking permission and guidance,” explains Regidor, who performs another blessing once construction is completed in each room (or when an already existing home is purchased). This rich Hawaiian culture, in addition to a laid-back and relaxing lifestyle, family-oriented community and an extremely friendly staff, plays a large role in enticing people from around the world to invest in a home at Hualālai, the master-planned residential community and private club that is located on exclusive Kona- Kohala coast on the leeward side of Hawai`i Island. Photo by Don Riddle A golf course at Hualalai on Hawaii Island. -

On the Wings of Luxury

The Layan Residences by Anantara are the latest destinations luxury arrival to Phuket’s shores; the interior of one of MJets’ private jets. PRIVATE JET ADVENTURES On the Wings of Luxury PROVIDING VIP AIRPORT ARRIVAL FROM RUNWAY TO SUITE VIA PRIVATE JET IS A SERVICE OFFERED BY A GROWING NUMBER OF FIVE-STAR RESORTS, exemplifying how the convenience and comfort of a smooth transition sits at the heart of today’s UHNWI lifestyle. OPULENCE IN THAILAND The magnificent Layan Residences by Anantara are the lat- est arrival to Phuket’s shores, providing unrivaled privacy in a sprawling haven overlooking the ocean. A stone’s throw from Layan Bay, and elevated above the existing Anantara Layan Phuket Resort, fifteen Arrive in style with services uniquely designed pool residences—each with live-in butler service—provide unsur- designed to get you from runway passed exuberance. Lazy days by the cliff-edge infinity pool, alfresco soirees bathed to private room in no time flat in starlight, and blissful in-residence spa and wellness journeys are all available at a by Julia Zaltzman moment’s notice, made accessible via MJets private jet charter. “Jet aviation saves time and forms an integral part of today’s world,” says William Heinecke, founder of MJets, the pioneer of the first and only fixed-base operation for private aviation in Thailand. Flying in from Thailand, Bangkok, New York, or London, the service takes guests and residents from runway to villa in minutes. SUMMER/AUTUMN 2019 I CAVIAR AFFAIR 37 PRIVATE JET ADVENTURES Clockwise from top left: qualia’s light-filled pavilions provide on-the-water vistas; aerial view of the Great Barrier Reef; the pool house at the Kayan Jet air terminal in Christophe Harbour on Saint Kitts; Baha Mar on Cable Beach, Nassau, is only accessible by private jet; the SLS Baha Mar. -

Island Real Estate in the Global Prime Sector WELCOME

ISLAND REAL ESTATE IN THE GLOBAL PRIME SECTOR WELCOME... PRIVATE PARADISE n this issue of the Candy GPS Report, produced CONTENTS in partnership with Deutsche Asset & Wealth The gaze of the ultra-high-net-worth individual (UHNWI) has settled upon the remotest of Management and featuring exclusive research from trophy assets – the private island. Anna White debates the allure of this real estate market I PRIVATE PARADISE with the experts from Candy & Candy, Savills and Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management Savills, we focus on island real estate around the world. Surrounded by water and finite in number, islands The ultimate trophy asset for ultra-high-net-worth individuals is a private island encapsulate much of what is desired by ultra-high-net- worth individuals (UHNWIs). They are both exclusive and rare, where the best properties carry a significant THE WORLD OF ISLAND REAL ESTATE price premium over their mainland counterparts. Our research looks in depth at these markets and pinpoints We have identified four primary and distinct island markets the hot spots around the globe. We also look at the sustainability of these islands and the rise of private planes that are putting them within easy reach. THE A LIST ARCHIPELAGO We rank the world's top islands for UHNWI investment PLANE TRUTHS Nicholas Candy Private jet planes put the remotest corners of the CEO, Candy & Candy earth within reach for UHNWIs ISLAND MARKETS IN FOCUS Whether it is for business, leisure or investment there is an island to suit your requirements Steele Point, Tortola world away from city super flats or star, the qualities "remote" and "private" are to create luxury resorts, wealthy conservationists countryside retreats, the purchase of a priceless.