CHAPTER 7 the Fint Journeys Across the Catibbean Sea Were Made By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fear and Money in Dubai

metropolitan disorders The hectic pace of capitalist development over the past decades has taken tangible form in the transformation of the world’s cities: the epic expansion of coastal China, deindustrialization and suburbanization of the imperial heartlands, massive growth of slums. From Shanghai to São Paolo, Jerusalem to Kinshasa, cityscapes have been destroyed and remade—vertically: the soar- ing towers of finance capital’s dominance—and horizontally: the sprawling shanty-towns that shelter a vast new informal proletariat, and McMansions of a sunbelt middle class. The run-down public housing and infrastuctural projects of state-developmentalism stand as relics from another age. Against this backdrop, the field of urban studies has become one of the most dynamic areas of the social sciences, inspiring innovative contributions from the surrounding disciplines of architecture, anthropology, economics. Yet in comparison to the classic accounts of manufacturing Manchester, Second Empire Paris or Reaganite Los Angeles, much of this work is strikingly depoliticized. Characteristically, city spaces are studied in abstraction from their national contexts. The wielders of economic power and social coercion remain anonymous. The broader political narrative of a city’s metamorphosis goes untold. There are, of course, notable counter-examples. With this issue, NLR begins a series of city case studies, focusing on particular outcomes of capitalist globalization through the lens of urban change. We begin with Mike Davis’s portrait of Dubai—an extreme concentration of petrodollar wealth and Arab- world contradiction. Future issues will carry reports from Brazil, South Africa, India, gang-torn Central America, old and new Europe, Bush-era America and the vertiginous Far East. -

15 Private Island Escapes

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For non-personal use, please contact us at 1-866-831-4314 or email [email protected]. INSIDE — NEW DISCOVERIES IN SOUTHERN FRANCE + FAVORITE PRIVATE ISLANDS WORLDWIDE ANDREW HARPER’S SEPTEMBER 2020 SINCE 1979 Traveling the world in search of truly enchanting places Pool at Le Vieux Castillon, Castillon-du-Gard Languedoc-Roussillon Revisited Rolling vineyards, exquisite villages, Roman ruins, open-air markets, profound tranquility he high-speed train from Paris the Cévennes mountains to the north True, visitors flock to Nîmes (pop. usually takes just under four and the Mediterranean to the south, 150,000), an ancient and atmospheric city T hours to reach Avignon, the Gard offers much of what American of great charm, as well as to Uzès, one of gateway to Provence. On leaving the city, travelers love about Provence but with France’s most beautiful towns, and to the most travelers drive southeast into the the added allure of being an unspoiled first-century Pont du Gard, the highest Vaucluse. However, if you cross to the and uncrowded area, where the traffic and most dramatic of Roman aqueduct west bank of the Rhône River, you enter on the plane tree-shaded back roads bridges. But much of Gard remains a the department of Gard in the region usually amounts to little more than a serene, village-dotted landscape planted of Languedoc-Roussillon. Bounded by tractor or two. with orchards and vineyards. -

79667 FCCA Profiles

TableTable ofofContentsContents CARNIVAL CORPORATION Mark M. Kammerer, V.P., Worldwide Cruise Marketing . .43 Micky Arison, Chairman & CEO (FCCA Chairman) . .14 Stein Kruse, Senior V.P., Fleet Operations . .43 Giora Israel, V.P., Strategic Planning . .14 A. Kirk Lanterman, Chairman & CEO . .43 Francisco Nolla, V.P., Port Development . .15 Gregory J. MacGarva, Director, Procurement . .44 Matthew T. Sams, V.P., Caribbean Relations . .44 CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES Roger Blum, V.P., Cruise Programming . .15 NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE Gordon Buck, Director, Port Operations. .16 Capt. Kaare Bakke, V.P. of Port Operations . .48 Amilicar “Mico” Cascais, Director, Tour Operations . .16 Sharon Dammar, Purchasing Manager, Food & Beverages . .48 Brendan Corrigan, Senior V.P., Cruise Operations . .16 Alvin Dennis, V.P., Purchasing & Logistics Bob Dickinson, President . .16 (FCCA Purchasing Committee Chairman) . .48 Vicki L. Freed, Senior V.P. of Sales & Marketing . .17 Colin Murphy, V.P, Land & Air Services . .48 Joe Lavi, Staff V.P. of Purchasing . .18 Joanne Salzedo, Manager, International Shore Programs . .49 David Mizer, V.P., Strategic Sourcing Global Source . .18 Andrew Stuart, Senior V.P., Marketing & Sales . .49 Francesco Morrello, Director, Port Development Group . .18 Colin Veitch, President & CEO . .49 Gardiner Nealon, Manager, Port Logistics . .19 Mary Sloan, Director, Risk Management . .19 PRINCESS CRUISES Terry L. Thornton, V.P., Marketing Planning Deanna Austin, V.P., Yield Management . .52 (FCCA Marketing Committee Chairman) . .19 Dean Brown, Executive V.P., Customer Service Capt. Domenico Tringale, V.P., Marine & Port Operations . .19 & Sales; Chairman & CEO of Princess Tours . .52 Jeffrey Danis, V.P., Global Purchasing & Logistics . .52 CELEBRITY CRUISES Graham Davis, Manager, Shore Operations, Caribbean and Atlantic . -

Pim-17-Digital.Pdf

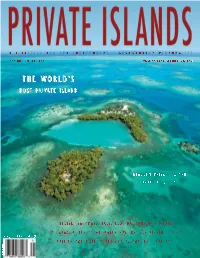

A L I F E S T Y L E F O R T H E I N D E P E N D E N T - A D V E N T U R O U S P E R S O N A L I T Y S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 0 1 7 W W W . P R I V A T E I S L A N D S M A G . C O M T H E WO R L D ’ S M O S T P R I VAT E I S L A N D G L A D D E N P R I VAT E I S L A N D B A R R I E R R E E F, B E L I Z E F I V E B A H A M I A N C R O W N J E W E L S B E L I Z E , B A H A M A S , I T A L Y , F L O R I D A , S A N J U A N I S L A N D S , N I C A R A G U A , T A H I T I , G E O R G I A N B A Y , B R I T I S H V I R G I N I S L A N D S , CAD $14.95 1 U.S. -

This Residential Resort for Billionaires on Hawaii Island Will Amaze You

/ Lifestyle / #DeLuxe MAY 1, 2018 @ 10:02 AM 1,479 2 Free Issues of Forbes This Residential Resort For Billionaires On Hawaii Island Will Amaze You Carrie Coolidge , CONTRIBUTOR FULL BIO Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own. Courtesy of Four Seasons Resort Hualalai The Palm Grove swimming pool at the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai. One of Earl “Uncle Earl” Regidor’s unofficial duties as Ka`upulehu Cultural Center Manager at the Four Seasons Resort Hualālai is performing a blessing at home sites before ground is broken. Home buyers at the sprawling luxury residential development that surrounds the Four Seasons Resort Hualālai often invite Uncle Earl to perform the ancient blessing to consecrate the land---once the site of an ancient fishing village---before building a new home. The blessing, which is attended by the homeowner’s family and their contractor, consecrates the land out of respect for the Hawaiian people who lived there for centuries before them. “I do the blessing for the sake of asking permission and guidance,” explains Regidor, who performs another blessing once construction is completed in each room (or when an already existing home is purchased). This rich Hawaiian culture, in addition to a laid-back and relaxing lifestyle, family-oriented community and an extremely friendly staff, plays a large role in enticing people from around the world to invest in a home at Hualālai, the master-planned residential community and private club that is located on exclusive Kona- Kohala coast on the leeward side of Hawai`i Island. Photo by Don Riddle A golf course at Hualalai on Hawaii Island. -

On the Wings of Luxury

The Layan Residences by Anantara are the latest destinations luxury arrival to Phuket’s shores; the interior of one of MJets’ private jets. PRIVATE JET ADVENTURES On the Wings of Luxury PROVIDING VIP AIRPORT ARRIVAL FROM RUNWAY TO SUITE VIA PRIVATE JET IS A SERVICE OFFERED BY A GROWING NUMBER OF FIVE-STAR RESORTS, exemplifying how the convenience and comfort of a smooth transition sits at the heart of today’s UHNWI lifestyle. OPULENCE IN THAILAND The magnificent Layan Residences by Anantara are the lat- est arrival to Phuket’s shores, providing unrivaled privacy in a sprawling haven overlooking the ocean. A stone’s throw from Layan Bay, and elevated above the existing Anantara Layan Phuket Resort, fifteen Arrive in style with services uniquely designed pool residences—each with live-in butler service—provide unsur- designed to get you from runway passed exuberance. Lazy days by the cliff-edge infinity pool, alfresco soirees bathed to private room in no time flat in starlight, and blissful in-residence spa and wellness journeys are all available at a by Julia Zaltzman moment’s notice, made accessible via MJets private jet charter. “Jet aviation saves time and forms an integral part of today’s world,” says William Heinecke, founder of MJets, the pioneer of the first and only fixed-base operation for private aviation in Thailand. Flying in from Thailand, Bangkok, New York, or London, the service takes guests and residents from runway to villa in minutes. SUMMER/AUTUMN 2019 I CAVIAR AFFAIR 37 PRIVATE JET ADVENTURES Clockwise from top left: qualia’s light-filled pavilions provide on-the-water vistas; aerial view of the Great Barrier Reef; the pool house at the Kayan Jet air terminal in Christophe Harbour on Saint Kitts; Baha Mar on Cable Beach, Nassau, is only accessible by private jet; the SLS Baha Mar. -

Island Real Estate in the Global Prime Sector WELCOME

ISLAND REAL ESTATE IN THE GLOBAL PRIME SECTOR WELCOME... PRIVATE PARADISE n this issue of the Candy GPS Report, produced CONTENTS in partnership with Deutsche Asset & Wealth The gaze of the ultra-high-net-worth individual (UHNWI) has settled upon the remotest of Management and featuring exclusive research from trophy assets – the private island. Anna White debates the allure of this real estate market I PRIVATE PARADISE with the experts from Candy & Candy, Savills and Deutsche Asset & Wealth Management Savills, we focus on island real estate around the world. Surrounded by water and finite in number, islands The ultimate trophy asset for ultra-high-net-worth individuals is a private island encapsulate much of what is desired by ultra-high-net- worth individuals (UHNWIs). They are both exclusive and rare, where the best properties carry a significant THE WORLD OF ISLAND REAL ESTATE price premium over their mainland counterparts. Our research looks in depth at these markets and pinpoints We have identified four primary and distinct island markets the hot spots around the globe. We also look at the sustainability of these islands and the rise of private planes that are putting them within easy reach. THE A LIST ARCHIPELAGO We rank the world's top islands for UHNWI investment PLANE TRUTHS Nicholas Candy Private jet planes put the remotest corners of the CEO, Candy & Candy earth within reach for UHNWIs ISLAND MARKETS IN FOCUS Whether it is for business, leisure or investment there is an island to suit your requirements Steele Point, Tortola world away from city super flats or star, the qualities "remote" and "private" are to create luxury resorts, wealthy conservationists countryside retreats, the purchase of a priceless. -

Vacation Hot Spot

Vacation Hot Spot February 19, 2019 No Place in World is More Popular than Caribbean for Cruise Holidays MIAMI, Feb. 19, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- For many people looking for a convenient and affordable way to take a great vacation, a favorite option is a cruise to the Caribbean. Year after year, consumers from around the world have made the Caribbean the world's most popular region for cruising. The reasons for the Caribbean's legendary status as a go-to option for cruise vacations are many. For one thing, many people can drive in a few hours to one of more than a dozen port cities in the U.S. to board a cruise ship and be whisked to the islands. That's a major convenience that also saves on the cost of air travel. For another, compared to similar land-based vacations, going on a cruise is a deal, often up to 40 and even 50 percent less expensive when factors such as lodging, meals, transportation and more are considered. And of course, there is something very appealing about the Caribbean, renowned for its always welcoming warm climate, breathtakingly beautiful scenery and relaxed island vibe. On Caribbean cruises, you escape to a place where the sky is bright blue and the sea is crystal clear. It is relaxing and invigorating, calming and energizing, all at the same time. Dig deeper and you'll also find an alluring history of Europeans, Africans, pirates, rumrunners and the Native Taino. Friendly locals willing to share their culture make a Caribbean vacation even more rewarding. -

Energy Snapshot British Virgin Islands

Islands Energy Snapshot British Virgin Islands British This profile provides a snapshot of the energy landscape Virgin Islands of the British Virgin Islands (BVI), one of three sets of the Virgin Island territories in an archipelago making up the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles. The 2015 electricity rates for BVI are of $0.16 to $0.24 per kilowatt- hour (kWh), lower than the Caribbean regional average of $0.33/kWh. Like many island nations, the BVI is The British Virgin Islands’ Renewable Energy Goal: almost 100% reliant on imported fossil fuels for electricity None generation, leaving it vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations that directly impact the cost of electricity. Government and Utility Overview Ministry: Ministry of Communications Population 32,680 Government and Works Authority Total Area 151 square kilometers Key Figure: Mark Vanterpool $0.5 billion Designated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) U.S. dollars (USD) Institution for None Renewable Energy Share of GDP Spent on Electricity – 1.2% Fuel and Imports Total – 4.8% Regulator British Virgin Islands Government GDP Per Capita $42,300 USD Name: British Virgin Islands Electricity Corporation Urban Population Share 40.8% Publicly Utilities Serves 15,250 customers. owned 100% of shares held by corporation the British Virgin Islands Electricity Sector Data Government. The British Virgin Islands Electricity Corporation (BVIEC) was formed by ordinance in 1978. As the territory’s sole util- ity, BVIEC is in charge of generation, transmission, supply, Clean Energy Policy Environment and distribution, all of which is generated from diesel fuel. Current law provides a monopoly to BVIEC, as is common Rates are designed in “declining block rates” so that custom- throughout the region. -

Top 10 Luxury Hotels You Can Buyout During the Pandemic

Top 10 luxury hotels you can buyout during the pandemic https://theluxurytravelexpert.com/2020/07/06/top-10-luxury-hotels-you-can-buyout-during-the... Top 10 luxury hotels you can buyout during the pandemic Monday newsletters always feature top 10 travel lists to inspire. Today (July 6, 2020): Top 10 luxury hotels that offer buyouts during the pandemic. Booking a full buyout of a luxury hotel is not a new thing for deep-pocketed travelers, but during these pandemic year of social distancing and minimal contact there has never been a better time. Resort buyouts are perfect for going ahead with your family vacation, reunion or private celebration, and making sure it is just the way you want it to be even during this challenging period. Each resort is operating as usual, and secures the entire premises – the rooms, restaurants, pool, spa and more – solely for your traveling group. If you are looking for an exclusive escape, here’s my selection of the best hotels & resorts in the world that you can buyout during the ongoing coronavirus outbreak. Think I forgot one? How do you feel about hotel buyouts? Leave a comment . 1 of 10 11/23/2020, 11:52 PM Top 10 luxury hotels you can buyout during the pandemic https://theluxurytravelexpert.com/2020/07/06/top-10-luxury-hotels-you-can-buyout-during-the... 9. SHELDON CHALET, ALASKA *** Follow me on Twitter , Instagram and Facebook for a daily moment of travel inspiration *** 10. ANANTARA SIR BANI YAS ISLAND RESORTS, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 2 of 10 11/23/2020, 11:52 PM Top 10 luxury hotels you can buyout during the pandemic https://theluxurytravelexpert.com/2020/07/06/top-10-luxury-hotels-you-can-buyout-during-the.. -

Whether You Prefer Stargazing Or Snorkelling, We've Got the Island For

AL I PEC S ISLANDS CALL OF THE ISLANDS WHETHER YOU PREFER STARGAZING OR SNORKELLING, WE’VE GOT THE ISLAND FOR YOU The ultra-exclusive Thanda Island in Tanzania. 26 \ LUXURY ESCAPES \ ISSUE NO . 02 LUXURY ESCAPES / ISSUE NO . 02 / 27 DiscONNect Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Caribbean Petit St Vincent Private Island Resort (petitstvincent.com) No WiFi, telephones or television make Petit St Vincent Private Island Resort the ultimate digital detox. Located on the southernmost island of the Grenadines, the resort has just 22 villas on 115 acres, so it’s not hard to see why it’s dubbed one of the world’s best hideaways. After a day relaxing, hit the hilltop restaurant for island-grown organic produce and a selection of more than 4,500 fine wines and exclusive champagnes. Qalito Island, Fiji Castaway Island (castawayfiji.com) Casual luxury is the calling card at Castaway Island (pictured below), where guests dine barefoot in the award-winning onsite restaurant on food sourced ISLANDS from local organic farms. There are 65 bures, all with traditional Fijian-style thatched roofs, set among 172 acres of tropical rainforest or at the S water’s edge, all without televisions, clocks, PEC radios or WiFi, to ensure you connect with I nature, not technology. AL e are a nation obsessed Pamalican Island, Philippines with island experiences. Whether Amanpulo (aman.com) it’s a secluded private island where you spend a week barefoot Pamalican is an A-listers go-to with guests on the beach, or somewhere you reportedly including the likes of Madonna, can explore the sights and visit Beyoncé and Brad Pitt. -

Fiji & Cook Islands

TAHITI FIJI & COOK ISLANDS LISA HOPPE TRAVEL CONSULTING 414-258-8715 [email protected] www.hoppetravel.com 2014 2015 TAHITI, FIJI & COOK ISLANDS PLEASANT HOLIDAYS DISTINCTION Trust the travel experts when it comes to booking vacations to U All-inclusive resorts and optional meal plans the South Pacifi c. In addition to a strong presence in Fiji and U Activities, tours and excursions Cook Islands, Pleasant Holidays is the No. 1 tour operator to U VIP airport lounge access Tahiti, providing everything travelers need for a memorable vacation including: Whether creating the ultimate fi ve-star honeymoon experience U Instant confi rmations on air and accommodations or a family-friendly trip to paradise, our size and scope give us U Customized itineraries unique purchasing power and we pass those savings along to U Multi-island vacations our customers. Pleasant Holidays also offers peace of mind U Inter-island transportation with round-the-clock customer service and travel protection U Cruises – from luxury vessels to chartered catamarans plans to help protect your investment. U Added values including free nights, resort credits and more V THE ISLANDS OF ROMANCE V Whether you’re seeking the ultimate honeymoon experience, a romantic escape for two or the family vacation of a lifetime, it’s hard to imagine a more idyllic paradise than the South Pacifi c. Tahiti offers islands crowned with majestic, emerald peaks, translucent turquoise waters and iconic overwater bungalows that are as luxurious as they are intimate. Home to the friendliest people on earth, explore the cobalt waters of Fiji, renowned for their soft coral diving, or stroll white-sand beaches kissed by the island breeze.