Actions of Enos's Division: Leaving the Expedition Without Permission and Its Effect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven External Factors That Adversely Influenced Benedict Arnold’S 1775 Expedition to Quebec

SEVEN EXTERNAL FACTORS THAT ADVERSELY INFLUENCED BENEDICT ARNOLD’S 1775 EXPEDITION TO QUEBEC Stephen Darley Introduction Sometime in August of 1775, less than two months after taking command of the Continental Army, Commander-in-Chief George Washington made the decision to send two distinct detachments to invade Canada with the objective of making it the fourteenth colony and depriving the British of their existing North American base of operations. The first expedition, to be commanded by Major General Philip Schuyler of Albany, New York, was to start in Albany and take the Lake Champlain-Richelieu River route to Montreal and then on to Quebec. The second expedition, which was assigned to go through the unknown Maine wilderness, was to be commanded by Colonel Benedict Arnold of New Haven, Connecticut.1 What is not well understood is just how much the outcome of Arnold’s expedition was affected by seven specific factors each of which will be examined in this article. Sickness, weather and topography were three external factors that adversely affected the detachment despite the exemplary leadership of Arnold. As if the external factors were not enough, the expedition’s food supply became badly depleted as the march went on. The food shortage was directly related to the adverse weather conditions. However, there were two other factors that affected the food supply and the ability of the men to complete the march. These factors were the green wood used to manufacture the boats and the return of the Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos Division while the expedition was still in the wilderness. -

Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas During the American Revolution Daniel S

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-11-2019 Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution Daniel S. Soucier University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S., "Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2992. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2992 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVIGATING WILDERNESS AND BORDERLAND: ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE IN THE NORTHEASTERN AMERICAS DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION By Daniel S. Soucier B.A. University of Maine, 2011 M.A. University of Maine, 2013 C.A.S. University of Maine, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School University of Maine May, 2019 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-Adviser Liam Riordan, Professor of History, Co-Adviser Stephen Miller, Professor of History Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History Stephen Hornsby, Professor of Anthropology and Canadian Studies DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Daniel S. -

Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland During the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775

Maine History Volume 47 Number 1 The Maine Borderlands Article 4 1-1-2013 “News of Provisions Ahead”: Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland during the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775 Daniel S. Soucier Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Geography Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S.. "“News of Provisions Ahead”: Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland during the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775." Maine History 47, 1 (2013): 42-67. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Benedict Arnold led an invasion of Quebec during the first year of the Revolu - tionary War. Arnold was an ardent Patriot in the early years of the war, but later became the most famous American turncoat of the era. Maine Historical Soci - ety Collections. “NEWS OF PROVISIONS AHEAD”: ACCOMMODATION IN A WILDERNESS BORDERLAND DURING THE AMERICAN INVASION OF QUEBEC, 1775 1 BY DANIEL S. S OUCIER Soon after the American Revolutionary War began, Colonel Benedict Arnold led an American invasion force from Maine into Quebec in an ef - fort to capture the British province. The trek through the wilderness of western Maine did not go smoothly. This territory was a unique border - land area that was not inhabited by colonists as a frontier society, but in - stead remained a largely unsettled region still under the control of the Wabanakis. -

Vermont Historical Society

~~~~~~~~~~~~!ID ~ NEW SERIES Priu 75cts. VoL. I No. 3 ~ ~ ~ ~ P czo c e e D 1 ~q s ~ ~ of the ~ ~ VERMONT ~ ~ Historical Society ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ @ A History of Irasburgh ~ ~ The Windham County Historical Society ~b) Berkshire Men at Bennington ~ A Scrabble for Life ~ The Orleans County Historical Society ~ (~~' PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY W~ Gil Montpelier Vermont 9 @ ~ ~ 1930 ~ ~~~~~~~~~W®W©© NEW SERIES VoL. I No. 3 PROCEEDINGS OF THE VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY A HISTORY OF IRASBURGH TO 1856 ANONYMOUS This account of the town which Ira Allen presented to his bride, Jerusha Enos, as a marriage settlement, is contained in a manu script never before published, in the archives of the Vermont Hist orical Society. From internal evidence it is clear that the account was written in I856, probably to be read before the "Natural and Civil History Society for Orleans County" of which mention is made elsewhere in this issue. There is no indication as to the author. The most unusual feature of the town's history is the fact that the land remained so long in the possession of the family of Ira Allen, under a system of leasing which resembled the English landlord and tenant system. This was, of course, a mere fraction of the vast landed estates of the Allen family in Vermont. and it is the only instance in which their leasing policy persisted. When this account was written, Kansas and the slavery question were uppermost in people's minds. Reference to The War means the War of I8I2. Smuggling at the time of that war, and the embargo which preceded it, remind one of similar difficulties along the border at present. -

Soldiers of the American Revolution Buried in Wisconsin

Soldiers of the American Revolution Buried in Wisconsin Published in 2011 by Wisconsin Society Sons of the American Revolution Prologue The United States of America became this great, independent country when our ancestors started and successfully won the American Revolution of 1776-1783. Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) is a society which got its start about the time of the first centennial anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1876 when a group of surviving ancestors of the Revolutionary Patriots formed a parade entry. The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution was founded on April 30, 1889, and incorporated by act of Congress June 9, 1906. Membership consists of male descendants of those Patriots who, during the American Revolution, rendered unwavering loyal service to the cause of winning our freedom from England. ----------------- The Wisconsin Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (WISSAR) is a state organization of the National Society with several active chapters. The year before the 1976 Bicentennial of the beginning of the American Revolution, WISSAR member Reverend Robert G. Carroon authored an article published in the Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee Country Historical Society, Vol. 31, No. 1, Spring, 1975, about the soldiers of the Revolution who found their final resting place within the boundaries of the State of Wisconsin. - 2 - Years later, the Wisconsin Society SAR embarked on a project of raising funds to purchase and install historical markers in cemeteries where these 40 patriots are buried. These 40 soldiers moved to the Territory of Wisconsin later in life and are buried in 25 cemeteries in Wisconsin. -

Benedict Arnold's Expedition to Quebec - Wikipedia

Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_Arnold's_expedition_to_Quebec In September 1775, early in the American Revolutionary War, Colonel Benedict Arnold led a force of 1,100 Continental Army troops on an expedition from Cambridge in the Province of Massachusetts Bay to the gates of Quebec City. The expedition was part of a two-pronged invasion of the British Province of Quebec, and passed through the wilderness of what is now Maine. The other expedition invaded Quebec from Lake Champlain, led by Richard Montgomery. Unanticipated problems beset the expedition as soon as it left the last significant colonial outposts in Maine. The portages up the Kennebec River proved grueling, and the boats frequently leaked, ruining gunpowder and spoiling food supplies. More than a third of the men turned back before reaching the height of land between the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers. The areas on either side of the height of land were swampy tangles of lakes and streams, and the traversal was made more difficult by bad weather and inaccurate maps. Many of the troops lacked experience handling boats in white water, which led to the destruction of more boats and supplies in the descent to the Saint Lawrence River via the fast-flowing Chaudière. By the time that Arnold reached the settlements above the Saint Lawrence River in November, his force was reduced to 600 starving men. They had traveled about 350 miles (560 km) through poorly charted wilderness, twice the distance that they had expected to cover. Arnold's troops crossed the Saint Lawrence on November 13 and 14, assisted by the local French-speaking Canadiens, and attempted to put Quebec City under siege. -

The American Defeat at Quebec

The American Defeat at Quebec Anthony Nardini Department of History Villanova University Edited by Cynthia Kaschub We were walking alongside the St. Lawrence River, along a roadway choked with cars. The small sidewalk was slick, covered in ice, the blustery wind pushing us down the street. I had thought the road would eventually lead back to the heart of the city, but I was wrong. We had become lost in Quebec, stuck between the great cliff the city was built upon and the river. It was here that I first became aware of what had transpired here over two hundred twenty-five years ago. A large plaque, attached to the facing rock, celebrated the bravery of the Canadians who pushed back American General Montgomery and his Rebel force. I wondered just what had happened at this very spot. What had happened to Montgomery and his men? Why were there Americans attacking Quebec City? Cause for Invasion On June 16, 1775, just two months after the clash at Lexington and Concord, the First Continental Congress appointed George Washington as “General & Commander in Chief of the American Forces.”1 By September 14, 1775, the day Washington gave orders to Colonel Benedict Arnold to “take Command of the Detachment from the Continental Army against Quebeck,” American forces had already seized Ticonderoga and Crown Point in New York.2 Earlier in September, an army of 2,000 under Brigadier General Richard Montgomery began to push towards Forts St. Jean and Chambly, in Canadian territory. The Americans were now poised for a full invasion of Canada, fueled by Washington’s belief, as stated by Donald Barr Chidsey, that, “the best defense is an offense and that it is best to keep your enemy off balance.”3 Controlling the Hudson and the Richelieu-Lake Champlain region would prevent the British from splitting the colonies in two. -

Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War Author(S): Ann M

Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease during the American Revolutionary War Author(s): Ann M. Becker Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Apr., 2004), pp. 381-430 Published by: Society for Military History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3397473 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 18:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for Military History is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Military History. http://www.jstor.org Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War Ann M. Becker Abstract The prevalence of smallpox duringthe early years of the American Warfor Independenceposed a very real danger to the success of the Revolution.This essay documents the impactof the deadly disease on the course of militaryactivities during the war and analyzes small- pox as a criticalfactor in the militarydecision-making process. Histo- rianshave rarelydelved intothe significantimplications smallpox held for eighteenth-centurymilitary strategy and battlefieldeffectiveness, yet the disease nearly crippledAmerican efforts in the campaigns of 1775 and 1776. Smallpox was a majorfactor duringthe American invasionof Canada and the siege of Boston. -

Pension Application for Edward Tylee W.1958 (Widow: Rebecca) Edward and Rebecca Married June 19, 1829

Pension Application for Edward Tylee W.1958 (Widow: Rebecca) Edward and Rebecca married June 19, 1829. Edward died October 18, 1850. B.L.Wt.9068-160-55 I Edward Tylee, of the Town of Nanburen in the County of Onondaga, and State of New York, do testify and declare, that I was born in the City of New York, on the twenty third day of October, in the year one thousand seven hundred and fifty seven and that in the spring of the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy six on or about the first of May I inlisted in the City of New York as a soldier in the United States Army for six months, in Captain Thomas Mitchel, Company in Colo William Malcom’s Regiment in General Scotts Brigade, and that I sustained the character of a Corporal, and that William Malcom was Colonel, and James Alner was Major of said Rigement, [sic] the Lieut Colonel I Cannot recollect, but I think our Adjutant was named Landford; our Lieut was Aspenwall Cornell the other I cannot recollect, our Ensign was Olive Lawrence, afterwards Aideecamp to General Parsons, as I have understood, after the Regiment was formed, we entered into Quarters, in Water Street in the City of New York, between Beekmans and [? Slips] shortly after we marched to our encampment at Greenwich, and the same day was fired upon by a Brittish [British] Man of war, said to be commanded by Capt. Wallace, called the Rosse, and about the midle [middle] of August our first Regiment (commanded by Colo Lasher) was ordered to Long Island to sustain general Washington, against the formidable British [Hostes?] -

Year-Book of the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American

1 _J 973.3406 MJ S6C2Y, 1892 GENEALOGY COL.L.ECTION «/ GC 3 1833 00054 8658 973.3406 S6C2Y, 1892 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 http://archive.org/details/yearbookofconnec1892sons <y^ <&2r~nt&sn~ By courtesy of Messrs. Belknap & War field, Publishers of Hollister's History of Connecticut. \TEAR-BOOK of the * CONNECTICUT SOCIETY OF THE SONS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION FOR 1892 Joseph Gurley Woodward Chairman Lucius Franklin Robinson Jonathan Flynt Morris Publication Committee Printed by THE CASE, LOCKWOOD & BRAINARD COMPANY in the year OF OUR LORD ONE THOUSAND EIGHT HUNDRED AND NINETY-THREE AND OF THE INDE- PENDENCE of the UNITED STATES the one hundred and eighteenth. Copyright, 1893 BY The Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution 1137114 CONTENTS. PAGE PORTRAIT OF ROGER SHERMAN. Frontispiece. BOARD OF MANAGERS, 1891-92 5 BOARD OF MANAGERS, 1892-93, 7 CONSTITUTION, 9 BY-LAWS, 14 INSIGNIA, i g PICTURE OF GEN. HUNTINGTON'S HOUSE Facing 23 THE THIRD ANNUAL DINNER AT NEW LONDON, FEBRUARY 22, 1892, .......... 23 REPORT OF THE ANNUAL MEETING, MAY 10, 1892, 51 ADDRESS OF THE PRESIDENT, 54 REPORT OF THE SECRETARY, 61 REPORT OF THE REGISTRAR, . .... 63 REPORT OF THE TREASURER, ...... 67 PORTRAIT OF GEN. JED. HUNTINGTON, . Facing 69 MEMBERSHIP ROLL, .69 • IN MEMOR1AM, . .251 INDEX TO NAMES OF REVOLUTIONARY ANCESTORS, . 267 BOARD OF MANAGERS, 1891-1892. PRESIDENT. Jonathan Trumbull, . Norwich. VICE-PRESIDENT. Ebenezer J. Hill, Norwalk. TREASURER. *Ruel P. Cowles, New Haven. John C. Hollister, . New Haven. SECRETARY. Lucius F. Robinson, Hartford. REGISTRAR. Joseph G. Woodward, Hartford. historian. Frank Farnsworth Starr, Middletown. -

Notes on the Ancestors and Immediate Descendants of Ethan and Ira Allen

NOTES ON THE ANCESTORS AND IMMEDIATE DESCENDANTS OF ETHAN AND IRA ALLEN With Additional Notes on the Ancestry of Reverend Thomas Allen, Known as "Fighting Parson Allen". BY JOHN SPARGO Bennington, Vermont 1948 PREFATORY NOTE In all the history of Vermont the most romantic character is Ethan Allen, "Old Ethan of Fort Ti". Vermont has had in its citizenry abler and better men, if we are to measure by any stand ards acceptable to reasonable men. It is impossible to read what he wrote about himself, or about events in which he participated, without reaching the conclusion that Ethan Allen rated highly his own talents and achievements as a statesman, a military leader and a writer. The truth is that, among his contemporaries, to say nothing of the succeeding generations, there were wiser and abler statesmen, and more competent military leaders than Ethan Allen. Both Thomas Chittenden and Nathar:.iel Chipman were his superiors in statecraft and political leadership. Seth Warner, certainly, and perhaps Samuel Herrick also, were superior to him as military leaders. And while Allen was unquestionably the outstanding literary protagonist of the Vermonters in their long struggle against the claims of New York, he was inferior to several others in literary craftsmanship. Both Stephen Rowe Bradley and Daniel Chipman excelled him in that. And there were many men of his day, as well as of succeeding generations, whose characters were more admirable and less open to serious criticism and censure than was the character of Ethan Allen. All this, and more, can be said with perfect justness and truth, and yet there can be no, denying that he holds a place of unchallenged and unapproached preeminence in the history of Vermont and in popular esteem. -

The Life of Benjamin Wait 0 0 I I

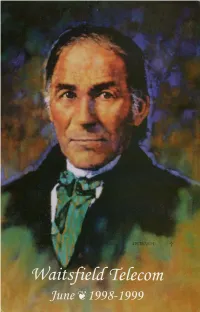

0 0 The Life of Benjamin Wait 0 0 I I I I Taken from a 1939 Sesquicentennial celebration pin, this reproduction of a drawing is the only known portrait of Wait. The artist is unknown. Wherea5 rr has been represented to us by our worthyfiiends the Honoruhle Roger Enm. Colonel Bmjamin Wait and company to the number of seventy, thnr there IT a tract of iacant land within this state, which has not been here- tofore grtrnted, M~ICIIthey pray may be granted to them. ” - Waitsfield Charter, Feb 25, 1782 Benjamin Wait came to the Mad River Valley in the spring of 1789 for the m purpose of setting up a homestead in a town that would bear his name. With the help of his sons and a few close friends, he built a temporary a cabin by the west bank of the river, and the arduous process of clearing the muddy, thawing ground began. There were ancient trees to be chopped down and hand-sawed into timber for building. Stumps had to be rooted out, underbrush burned and the New England soil cleared of its endless wealth of stones in preparation for tilling and planting. Every town began in such humble fashion. The settling of the northeastern territories of the New World was under- taken by a breed of young men and women whose character remains the backbone of New England mythology. A product of the most stringent ideals of Puritanism, New Englanders, perhaps above all other colonists, possessed the single-mindedness and spiritual determination to stand up to the howl- Written by David W Smith Photography by Stefan Hard 0 1 ing winds of winter, and fmiland that revealed only small glimpses of its richness after incredible patience and backbreaking toil.