Bangkok's Decentered Spaces of Security and Public Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

Experience the Diverse Lifestyle

176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. Street food is as delicious as that provided in restaurants, ranging from barbeque skewers to fresh seafood, and even international cuisine. One of the best ways to explore Bangkok is to take a stroll along the following roads as they reflect the everyday city life of the local people. Bangkok City Printed in Thailand by Promotional Material Production Division, Marketing Services Department, Tourism Authority of Thailand for free distribution. www.tourismthailand.org E/MAR 2019 The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. 62-02-134_A+B-Colourful Bkk new22-3_J-CoatedUV.indd 1 62-02-134_A-Colourful street Life in Bangkok new22-3_J-CC2018 Coated UV 22/3/2562 BE 18:18 176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. -

Download This PDF File

“PM STANDS ON HIS CRIPPLED LEGITINACY“ Wandah Waenawea CONCEPTS Political legitimacy:1 The foundation of such governmental power as is exercised both with a consciousness on the government’s part that it has a right to govern and with some recognition by the governed of that right. Political power:2 Is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labor, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. Demonstration:3 Is a form of nonviolent action by groups of people in favor of a political or other cause, normally consisting of walking in a march and a meeting (rally) to hear speakers. Actions such as blockades and sit-ins may also be referred to as demonstrations. A political rally or protest Red shirt: The term5inology and the symbol of protester (The government of Abbhisit Wejjajiva). 1 Sternberger, Dolf “Legitimacy” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (ed. D.L. Sills) Vol. 9 (p. 244) New York: Macmillan, 1968 2 I.C. MacMillan (1978) Strategy Formulation: political concepts, St Paul, MN, West Publishing; 3 Oxford English Dictionary Volume 1 | Number 1 | January-June 2013 15 Yellow shirt: The terminology and the symbol of protester (The government of Thaksin Shinawat). Political crisis:4 Is any unstable and dangerous social situation regarding economic, military, personal, political, or societal affairs, especially one involving an impending abrupt change. More loosely, it is a term meaning ‘a testing time’ or ‘emergency event. CHAPTER I A. Background Since 2008, there has been an ongoing political crisis in Thailand in form of a conflict between thePeople’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the People’s Power Party (PPP) governments of Prime Ministers Samak Sundaravej and Somchai Wongsawat, respectively, and later between the Democrat Party government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD). -

The Okura Prestige Bangkok the Okura Prestige Bangkok Is a Stylish, Luxurious and Contemporary Ve-Star Hotel Offering Unrivalled Levels of Comfort and Convenience

The Okura Prestige Bangkok The Okura Prestige Bangkok is a stylish, luxurious and contemporary ve-star hotel offering unrivalled levels of comfort and convenience. All 240 rooms and suites enjoy impressive views through e-coated triple-glazed windows that insulate against heat and sound. Our restaurants provide outstanding dining options that cater for every social and business occasion. The hotel offers a functional, exible venue for weddings, gala dinners, conferences and other special events, plus a spectacular 25-metre cantilevered swimming pool, tness centre and Okura Spa. Access is easy from the BTS SkyTrain network at Phloen Chit station and there is ample on-site parking. The Okura Prestige Bangkok. The perfect choice for business and leisure travellers. The 240 rooms and suites, located on oors 26 to 34, are designed to meet the needs of business and leisure travellers by combining contemporary, elegant styling with maximum comfort and convenience. Guests appreciate our ne Egyptian cotton bed linen, the at-screen internet TVs and the environmentally-friendly bathroom amenities. Every room enjoys stunning city views through oor-to-ceiling triple glazed windows. Room Type Sqm. No. of Units Deluxe 47 112 Grand Deluxe 43 44 Deluxe Corner 55 24 Okura Club 43 16 Premier Club 57 21 Prestige Club 65 5 Deluxe Suite 80 8 Prestige Suite 97 7 Presidential Suite 156 1 Royal Suite 165 1 Imperial Suite 302 1 Room Facilities • Large at-screen LED TV with internet access and satellite channels • Work desk with multimedia panel • Complimentary LAN and wireless internet access • Bedside touchscreen control panel • Modern Japanese style lavatory with separate room for bathtub and shower • Bespoke bathroom amenities • Fully stocked refreshment cabinet • Coffee maker • Egyptian cotton bed linen • Iron & ironing board • Kettle • Safety box • PressReader (digital newspapers) The Okura Prestige Bangkok provides three fantastic dining options at Up & Above, Elements and our signature Japanese restaurant Yamazato. -

Logistics Sheet

Asia Pacific Think Tank Summit 10 November 2019 - 12 November 2019 Think Tanks & Civil Societies Program The Lauder Institute The University of Pennsylvania “Helping to bridge the gap between knowledge and policy” Researching the trends and challenges facing think tanks, policymakers, and policy-oriented civil society groups... Sustaining, strengthening, and building capacity for think tanks around the world... Maintaining the largest, most comprehensive database of over 8,000 think tanks... All requests, questions, and comments should be directed to: James G. McGann, Ph.D. Senior Lecturer, International Studies Director Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program The Lauder Institute University of Pennsylvania 1 2019 ASIA PACIFIC THINK TANK SUMMIT LOGISTICS INFORMATION Abbreviated Summit Schedule Sunday, November 10 2019 Venue: Anantara Siam Hotel Pimarnman Foyer and Anantara Siam Hotel Pimarnman 1 12:00 - 17:00 Hotel Check-in 18:00 - 18:15 Registration 18:15 - 18:30 Welcoming Remarks 18:30 - 19:30 Asia Pacific Think Tanks Presidents Panel 19:30 - 20:00 Welcome Buffet Dinner 20:00 - 20:30 Keynote Address 20:00 - 20:30 Buffet Dessert, Coffee and Tea Monday, November 11 2019 Venue: United Nations Conference Center and Grand Centre Point 07:30 Buses Depart from Hotel to UN Conference Center 08:30 - 09:00 Participant Registration 09:00 - 09:15 Summit Opening Remarks 09:15 - 09:40 Opening Keynote Address 09:40 - 10:55 Plenary (1st Session): Trade Wars or Trade Winds, which way is the Wind Blowing? 2 10:55 - 11:15 Coffee -

Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011

Thai Netizen Network Annual Report: Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011 An annual report of Thai Netizen Network includes information, analysis, and statement of Thai Netizen Network on rights, freedom, participation in policy, and Thai internet culture in 2011. Researcher : Thaweeporn Kummetha Assistant researcher : Tewarit Maneechai and Nopphawhan Techasanee Consultant : Arthit Suriyawongkul Proofreader : Jiranan Hanthamrongwit Accounting : Pichate Yingkiattikun, Suppanat Toongkaburana Original Thai book : February 2012 first published English translation : August 2013 first published Publisher : Thai Netizen Network 672/50-52 Charoen Krung 28, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Thainetizen.org Sponsor : Heinrich Böll Foundation 75 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidee-Madee) North Klongton, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand The editor would like to thank you the following individuals for information, advice, and help throughout the process: Wason Liwlompaisan, Arthit Suriyawongkul, Jiranan Hanthamrongwit, Yingcheep Atchanont, Pichate Yingkiattikun, Mutita Chuachang, Pravit Rojanaphruk, Isriya Paireepairit, and Jon Russell Comments and analysis in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the Thai Netizen Network which will be stated clearly Table of Contents Glossary and Abbreviations 4 1. Freedom of Expression on the Internet 7 1.1 Cases involving the Computer Crime Act 7 1.2 Internet Censorship in Thailand 46 2. Internet Culture 59 2.1 People’s Use of Social Networks 59 in Political Movements 2.2 Politicians’ Use of Social -

Incendiary Central: the Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng

Urbanities, Vol. 2 · No 1 · May 2012 © 2012 Urbanities Incendiary Central: The Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng (Independent Anthropologist, Bangkok) [email protected] In May 2010, anti-government demonstrators made a flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza – Thailand’s biggest, and Asia’s second largest, shopping mall. It was the climax of the latest major chapter of the Thai political conflict, during which thousands of protestors swarmed Ratchaprasong, the commercial centre of Bangkok, in an ultimately failed attempt to oust Abhisit Vejjajiva’s regime from power. In this article, I examine how downtown Bangkok and exclusive malls like CentralWorld represent physical and cultural spaces from which the marginalized working classes have been strikingly excluded. It is a configuration of space that maps the contours of a heavily uneven distribution of power and articulates a vernacular of prestige wherein class relations are inscribed in urban space. The significance of the Red-Shirted movement’s occupation of Ratchaprasong lies in the subversion of this spatialisation of power and draws attention to the symbolic deployment of space in the struggle for political supremacy. Keywords: Bangkok, protest, space, class, politics, consumption, mall Introduction: The Burning Centre In late May 2010, billowing charcoal smoke rose from the Ratchaprasong district in central Bangkok, casting a dark pall over the sprawling city. Much of it came from the flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza, Thailand’s biggest, and Southeast Asia’s second largest, shopping mall.1 What will likely become one of the most iconic images of the conflagration is a photo by Adrees Latif of Reuters featuring a huge golden head with the likeness of a female deity in a square in front of the mall, her eyes seemingly wide with surprise as a tattered Thai flag fluttered pitifully overhead and the 500.000 metre square complex blazed in the background (see Image 1). -

Thailand's Internal Nation Branding

Petra Desatova, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies CHAPTER 4: THAILAND’S INTERNAL NATION BRANDING In commercial branding, ambassadorship is considered a crucial feature of the branding process since customers’ perceptions of a product or a service are shaped through the contact with the employees who represent the brand. Many companies thus invest heavily into internal branding to make sure that every employee ‘lives the brand’ thereby boosting their motivation and morale and creating eager brand ambassadors.1 The need for internal branding becomes even more imperative when it comes to branding nations as public support is vital for the new nation brand to succeed. Without it, nation branding might easily backfire. For example, the Ukrainian government was forced to abandon certain elements of its new nation brand following fierce public backlash.2 The importance of domestic support, however, goes beyond creating a favourable public opinion on the new nation brand. As Aronczyk points out, the nation’s citizens need to ‘perform attitudes and behaviours that are compatible with the brand strategy’ should this strategy succeed. This is especially the case when the new nation brand does not fully reflect the reality on the ground as nation branding often produces an airbrushed version rather than a truthful reflection of the nation, its people, and socio-political and economic conditions. Although some scholars are deeply sceptical about governments’ ability to change citizens’ attitudes and behaviours through nation branding, we should not ignore such attempts.3 This chapter examines Thailand’s post-coup internal nation branding efforts in the education, culture, public relations and private sectors: what were the political motivations behind these efforts? I argue that the NCPO was using internally focused nation branding to diffuse virtue across Thai society in preparation for the post-Bhumibol era. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ROBINSON DEPARTMENT STORE PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED WWW.ROBINSON.CO.TH ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CONTENTS 05 Vision and Mission 10 Message from Chairman and President 18 Financial Highlights 44 21 Dividend Policy 5 Years Major Development 45 23 Organization Chart Structure of the Company and Its Subsidiaries 46 Management Structure 111 55 Statement of Corporate Governance the Directors Responsibility 79 112 Board of Directors and Connected Transactions Managements 117 99 Management Discussion 26 Corporate Social Responsibility and Analysis Nature of Business 105 120 34 Internal Control Independent Auditor Report Risk Factors and Risk Management and Financial Statements 41 108 207 Shareholder Structure Report of the Audit Committee General Information TO PUT OUR CUSTOMERS, EMPLOYEES AND SUPPLIERS AT THE HEART OF OUR BUSINESS DECISIONS Vision To profitably grow our market share Mission To put our customers employees and suppliers at the heart 1 of our business decisions To be locally relevant in our merchandising 2 offering and our shopping experience To increase sales by attracting new customers, expanding 3 our customer base and increasing customer spend 4 To make retail more than just shopping 5 To invest in the future growth of our stores and people A Professional and Entrepreneurial 6 approach by our management team Attracting, retaining and growing the most 7 talented people in the Retail Industry Exceeding the expectations of our 8 shareholders, customers and employees AIN RETAI MORE THAN UST SHOPPING And with the rise of prevalent health trends, health and sport enthusiasts will find delight in our Fitbo - the latest trendy fitness center which is well - equipped with a team of professional trainers. -

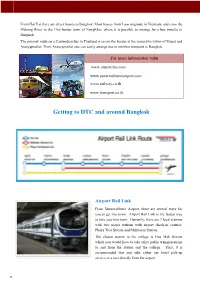

Getting to DTC and Around Bangkok

From Hat Yai there are direct busses to Bangkok. Most busses from Laos originate in Vientiane and cross the Mekong River to the Thai border town of NongKhai, where it is possible to arrange for a bus transfer to Bangkok. The primary route on a Cambodian bus to Thailand is across the border at the respective towns of Poipet and Aranyaprathet. From Aranyaprathet one can easily arrange bus or minibus transport to Bangkok. For more information visit: www.airportthai.com www.suvarnabhumiairport.com www.railway.co.th www.transport.co.th Getting to DTC and around Bangkok Airport Rail Link From Suvarnabhumi Airport, there are several ways for you to get into town. Airport Rail Link is the fastest way to take you into town. Currently, there are 7 local stations with two major stations with airport check-in counter: Phaya Thai Station and Makkasan Station. The closest station to the college is Hua Mak Station which you would have to take other public transportations to and from the station and the college. Thus, it is recommended that you take either our hotel pick-up service or a taxi directly from the airport. 8 Taxi All 30,000+ taxis cruising Bangkok city streets are metered and are required by law to use them. If a taxi offers you a fixed-price fare, politely ask to use the meter. If not, then flag down another taxi. In general, parked taxis will ask for fixed fares while those already driving will generally use the meter. Taxis using the meter charge a minimum of 35 baht for the first 3 kilometers. -

Useful Information for Participants Asia-Pacific Digital Societies Policy Forum 2017

Useful Information for Participants Asia-Pacific Digital Societies Policy Forum 2017 USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS 1. Meetings The Asia‐Pacific Digital Societies Policy Forum 2017 is organised by ITU and GSMA with support from the Australian Government during 8‐9 May 2017. More detail at, http://www.itu.int/go/digital2017 2. Venue Centara Grand & Bangkok Convention Centre at Central World 999/99 Rama I Road, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel: +66 (0)2 100 1234 | Fax: +66 (0)2 100 1235 | Email: [email protected] www.centarahotelsresorts.com 3. Visa and Immigration Requirements To enter Thailand, all participants must possess a valid passport or accepted travel document. Participants who require a visa should apply for a visa at a Royal Thai Embassy or a Royal Thai Consulate‐General in their respective country well in advance of their departure. For nationals of some countries, it may take up to two weeks for visa processing. As visa requirements change from time to time, please check with your nearest Royal Thai Embassy/Consulate‐General for your visa requirements. You are also advised to visit http://www.mfa.go.th for more information on visas and travel documents. The following is the list of countries and territories entitled for visa exemption and visa on arrival to Thailand: Useful Information for Participants Asia-Pacific Digital Societies Policy Forum 2017 Summary of Countries and Territories entitled for Visa Exemption and Visa on Arrival to Thailand Ordinary Passport Diplomatic/Official Passport Nationals of