What Would It Look Like If Community Co-Created Curriculum?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronological Outline for the Athabasca Lowlands and Adjacent Areas

6 A Chronological Outline for the Athabasca Lowlands and Adjacent Areas brian o. K. rEEves, JanEt blaKEy, and Murray lobb Since the early 1970s, archaeological studies in the Athabasca lowlands and the Birch Mountains have recorded a large number of sites that contain significant numbers of stone tools, including diagnostic artifacts, among them projectile points (fig 6.1). While some of the earlier studies originated in academic research, most of them have taken place in connection with proposed oil sands development or local or regional infrastructure projects. Our intent in this chap- ter is to outline, refine, and update the cultural chronology of the Lower Athabasca region in the light of existing studies and on the basis of the provincial database of archaeological sites. PaSt chronological Studies The first generalized chronologies of the Athabasca lowlands and adjacent areas date to the mid-1970s and were based on reconnaissance surveys, test excava- tions, and detailed excavations carried out by Archaeological Survey of Alberta staff archaeologists Paul Donahue (1976), John Ives (1977), and John Pollock (1978b). The results of these studies were later summarized by Ives (1981). Detailed discussions of chronology also appeared in the Historical Resource Impact Assessment reports pertaining to two major oil sands leases, Shell’s Alsands Lease 13 (Ronaghan 1981a, 1981b) and Syncrude Lease 22 (Van Dyke and Reeves 1984). Ives (1993) subsequently provided an in-depth discussion of the doi: 10.15215/aupress/9781926836904.01 161 r ! e v i R t r R o i F c Figure 6.1. Lower Athabasca study k h ee d Cr r a l area. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Genetic Population Structure of Walleye (Sander vitreus) in Northern Alberta and Application to Species Management by Lindsey Alison Burke A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Systematics and Evolution Biological Sciences ©Lindsey Alison Burke Fall 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62977-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62977-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque -

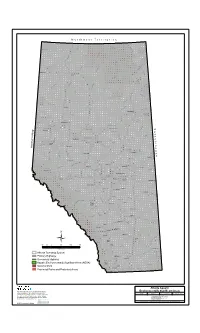

Alberta Aquatic Environmentally Significant Areas

N o r t h w e s t T e r r i t o r i e s 127 126 127 126 125 r e iv 125 124 R s r e uff e t 124 B alo iv 123 le S a R t t la Riv Y i Petito t er ve L 123 122 R i v 122 e 121 r r e v i 121 120 R o l 120 119 r a f e f v u i B 119 118 R y a H 118 117 117 116 r e v 116 i 115 R e 115 c 114 a a e c r P s a e 114 b 113 v a i r th R ve 113 A 112 i e n R o k t l a n e L 111 o z 112 t P n e 111 Clare Lake O 110 Rainbow Lake W ld " F o 110 r 109 " t R i High Level 109 v 108 e r 108 er 107 Riv ch R Bir i c 106 107 h a rd 106 s 105 o n r e M R 104 v 105 i i v i k e R k r e w c 104 103 iver a a R e a R g P 13 i 12 11 10 a v 103 3 2 1102 9 8 7 h e 6 5 4 6 5c 4 3 10 9 8 7 in 2 1 25 24 r 13 12 11 23 22 21 20 19 19 18 17 16 15 14 h 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1021 25 24 23 22 21 20 101 C 101 100 B u ff 100 99 a l r o e 99 98 R v iv i F R ir e eba r 98 a g 97 c Riv s er W Namur Lake a 97 b 96 a a b h a t s 96 A 95 c a r R e 95 iv 94 iv e R r Ells 94 93 No tikewin Ri 93 92 ver 91 92 r " e Manning iv 91 R 90 ay r R K ate iver ac rw r 90 a 89 e M le v " i C C R 88 a 89 Fort McMurray d n o o t o t 87 e L 88 Gordon Lake R iver 87 86 86 85 85 84 84 83 " Peace River 83 82 82 81 P North Wabasca Lake e a 81 r 80 ce e R iver iv R 80 79 South Wabasca Lake a S in B t is 78 " Utikuma Lake 79 r Spirit River h r C a 77 i 78 Sandy Lake t i 76 s s 77 r h e 75 76 v i k R Winefred Lake a C 75 74 c r s Lesser Slave Lake a a e " o v b 73 i 74 a R High Prairie h l t y u t 73 A 72 k o " m m Slave Lake 72 71 c ! S Calling Lake b GRANDE i Riv 71 70 t er h api PRAIRIE i W " a 70 69 Valleyview e 69 68 68 r 67 w Lac la Biche e v r ' i r e e " R 66 v 67 iv i d R R a n Lac la Biche e y " 66 a 65 t t k Swan Hills S o e n m 64 n o 65 S m i e l S t t ! 63 i 64 Cold Lake L ave r 63 Be r R 62 e ive v r Ri " a 61 kw Fox Creek 62 Ka 61 60 ver Ri ca 59 as 60 Westlock ab " th " " 14 13 A 2 581 12 11 10 er 59 5 4 3 9 8 7 6 iv Whitecourt Smoky Lake 8 7 6 5 4 R 10 9 3 2 1 d 13 12 11 " 27 2a6n 25 24 23 18 17 16 15 14 rl 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 St. -

Vessel Operation Restriction Regulations Règlement Sur Les Restrictions Visant L’Utilisation Des Bâtiments

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Vessel Operation Restriction Règlement sur les restrictions Regulations visant l’utilisation des bâtiments SOR/2008-120 DORS/2008-120 Current to June 20, 2019 À jour au 20 juin 2019 Last amended on October 10, 2018 Dernière modification le 10 octobre 2018 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Alberta Archaeological Review

ALBERTA ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIEW Number 3 ISSN 0701-1776 Autumn 1981 Copyright © 1981 by the publisher, The Archaeological Society of Alberta Archaeological Society of Alberta SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1981-82 EDITOR'S NOTE This issue of the REVIEW appears in a new format. Its President: Nick Sheptycki purpose is two-fold: to convey news of the sponsoring 5811-113A Street organization's activities throughout the province, and to Edmonton, Alberta T6H 1A9 provide a forum for news and comment of value to all who 434-2316 may be interested in the archaeological heritage of Alberta. Past President: J.T. Humphreys This will be possible if readers provide the Editor with 2139 - 29th Avenue S.W. pertinent news items, brief reports or comments, illustrated Calgary, Alberta T2T 1N6 if possible with black and white photographs. It is hoped 244-8793 that the REVIEW will be a meeting ground for both amateur Vice-President: Michael Quigg and professional archaeologists. I invite your comment and 307 - 7th Street S.E. suggestions. If response is sufficient two issues per year will Medicine Hat, Alberta be published. An illustrated book containing papers pres ented at the 1980 Annual Meeting in Lethbridge will be 529-9249 published later this year. Secretary-Treasurer: Mary Sheptycki 5811 -113A Street I wish to express my appreciation to the former editor, Edmonton, Alberta T6H 1A9 Ron Getty, for his co-operation, and to Duncan Mackintosh 434-2316 and Lawrence Halmrast for their encouragement, and to Edmonton Centre: President G.F. Paschen the Provincial Executive of the Archaeological Society of 11911 University Drive Alberta for their support. -

Wildlife Regulation

Province of Alberta WILDLIFE ACT WILDLIFE REGULATION Alberta Regulation 143/1997 With amendments up to and including Alberta Regulation 148/2013 Office Consolidation © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer 5th Floor, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this consolidation are reminded that it has no legislative sanction, that amendments have been embodied for convenience of reference only. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. (Consolidated up to 148/2013) ALBERTA REGULATION 143/97 Wildlife Act WILDLIFE REGULATION Table of Contents Interpretation and Application 1 Establishment of certain provisions by Lieutenant Governor in Council 2 Establishment of remainder by Minister 3 Interpretation 4 Interpretation for purposes of the Act 5 Exemptions and exclusions from Act and Regulation 6 Prevalence of Schedule 1 7 Application to endangered animals Part 1 Administration 8 Terms and conditions of approvals, etc. -

Winter Lakekeepers 2019

Winter LakeKeepers 2019 ALBERTA LAKE MANAGEMENT SOCIETY’S OBJECTIVES ALMS has several objectives, one of which is to collect and interpret water quality data on Alberta Lakes. Equally important is educating lake users about their aquatic environment, encouraging public involvement in lake management, and facilitating cooperation and partnerships between government, industry, the scientific community and lake users. ALMS would like to thank all who express interest in Alberta’s aquatic environments and particularly those who have participated in the LakeKeepers program. These leaders in stewardship give us hope that our water resources will not be the limiting factor in the health of our environment. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The LakeKeepers project was made possible with support from Alberta Ecotrust. We would like to thank the volunteers who made this program happen: Jon Pedlan, Ray Walker, Vien and Marielle Lam, Cam and Brittany Kereliuk, Kellie Nichiporik, Steve Hawryliw, and Blake Mills. We would also like to thank the Mighty Peace Watershed Alliance, the Alberta Conservation Association, and the Calling Lake Cottage Association for their assistance with coordinating volunteers and sample shipment. A special thanks to Cerina Lee for developing the LakeKeeper training videos. This report has been prepared by Caitlin Mader, Bradley Peter, Patrick Heney, and Caleb Sinn. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 2018, the Alberta Lake Management Society, with financial support from Alberta Ecotrust, piloted the LakeKeepers project. This project was designed to enable stewards to conduct lake monitoring by providing them with training and sampling equipment. In early 2019, this project was expanded to include winter under-ice sampling, with the cooperation of ice anglers. -

2019-2020 Fisheries Regulation Changes Online Consultation Summary 1

Alberta Environment and Parks, Government of Alberta January 2019 2019-2020 Fisheries Regulation Changes Online Summary URL of document to be assigned by communications Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 1 SURVEY ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Approach ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Participation ................................................................................................................................. 4 Response ..................................................................................................................................... 4 RESULTS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Affiliation of Survey Participants .................................................................................................. 5 Summary of Management Objectives .......................................................................................... 6 Detailed Survey Results ............................................................................................................... 8 ES2 – Jackfish Lake ................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2009/2010 Annual Report 2009/2010

Annual Report 2009/2010 Annual Report 2009/2010 For copies of this document, contact: Alberta Conservation Association 101 – 9 Chippewa Road Sherwood Park, AB T8A 6J7 Tel: (780) 410-1999 Fax: (780) 464-0990 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ab-conservation.com Our Mission ACA conserves, protects and enhances fish, wildlife and habitat for all Albertans to enjoy, value and use. Our Vision An Alberta with an abundance and diversity of fish, wildlife and their habitat; where future generations continue to use, enjoy and value our rich outdoor heritage. TM Charitable Registration Number: 88994 6141 RR0001 Cover Photo: Marco Fontana, Biologist, ACA is conducting Bull Trout stock assessments. Our fisheries studies on the Upper Oldman River and North Saskatchewan River systems have resulted in the protection and conservation of key spawning and rearing habitat in both watersheds. Contents About Us ................................................5 Chairman’s Report .................................6 President and CEO’s Message ..............7 Conservation Milestones .......................8 Our People Our Culture .........................9 Health and Safety ...........................10 Human Resources ..........................11 Information Technology ..................11 10 Years with ACA ..........................12 Conservation Programs .......................15 Communications ............................16 Wildlife ............................................18 Fisheries .........................................28 Land Management -

Indigenous Tourism Investment Guide Introduction 2 Nikan

Alberta North Central: an Indigenous Tourism Investment Guide Introduction 2 Nikan Partners 3 Wiciwakanahtowin Wabasca 7 Wapiskaw Athabasca 10 Kapawinih Calling Lake 13 Kitohosakiyahkan 10 Major Ideas 16 Mitataht kiway mamiskotamok 1. Links & Resources 17 Introduction Nikan The Athabasca Native Friendship Centre is inviting you to explore the power of Indigenous Tourism. In the Fall of 2018 the Athabasca Native Friendship Centre partnered with the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada, the newly formed Alberta Indigenous Tourism Association and Alberta Culture and Tourism to explore some potential for Indigenous Tourism opportunities that exist in our region. We focused on the communities of Wabasca, Athabasca and Calling Lake to host day long workshops. Each of our partners presented information about their organization and the benefits created through Indigenous Tourism. In the afternoon participants shared some ideas they had about their community including community assets, barriers that exist and of course the potential that abounds for entrepreneurs, investors and collaborations! Here is a bit about our partners and what they shared. Kapawinihk waskayihkan ayatwaw Nehiyawa ohci wiyawa wisamiskwaw kistawaw takwi wisawtamik Nehiyanah tapikiyokit ekwa wapahta mastaw ayisino kitaskiwaw. Wiciwakanimitotwaw nikik “ANFC” Kapawinihk waskayihkan ayatwaw Nehiyawa ohci ekwa Nikik “ITAC”(Pikiyohkik Nehiyanahk Kakanata) Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada nohti nosohkamowat Nehiyawa tamacihtayi kikway omsi sihcikiwin Kitosakayihkan “Calling -

View to the Southeast of the Study Area

Golder Associates Ltd. 1oth Floor, 940 6th Avenue S.W. Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2P 3Tl Telephone (403) 299-5600 Fax (403) 299-5606 REPORT ON IDSTORICAL RESOURCES IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR SUNCOR'S PROJECT MILLENNIUM. PERMIT #97-123 Submitted to: Suncor Energy Inc., Oil Sands Fort McMurray, Alberta Prepared by: Grant M. Clarke Golder Associates ltd. Calgary, Alberta October 1998 972-2205 OFFICES IN AUSTRALIA CANADA GERMANY, HUNGARY, ITALY, SWEDEN, UNITED KINGDOM, UNITED STATES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the autumn of 1997, Golder Associates Ltd. completed an Historical Resources Impact Assessment (HRIA) on behalf of Suncor Energy Inc. (Suncor). This HRIA was completed to investigate lands proposed for disturbance during construction and operation of Suncor's Project Millennium. Project Millennium is located on the south and east sides of the Steepbank Mine, north of Fort McMurray. All work completed for this Project was conducted under Historical Resources Permit #97-123, issued by Alberta Community Development to Grant Clarke. The field assessment was completed under the direction of Mr. Clarke. Field crews varied in size from three to five archaeologists and included Grant Clarke, Brian Ronaghan, Dana Dalmer, Sid Rempel and Terry Beaulieu. The Millennium Project will impact portions of four Townships of land including T91-R09, T92- R09, T91-R08 and T92-R08-W4M. Due to the fact that the project encompasses large tracts of land covered by fens and other areas exhibiting varying degrees of potential for historical resources, a vegetation and hydrology based model was used to define areas of high, moderate and low potential prior to the initiation of field work. -

Winter Lake Keepers

WINTER LAKE KEEPERS 2019Pilot Project • Smaller, more mobile alternative to LakeWatch • Summer program running since 2018 • Kits are mailed out to volunteers, measure independently, ship data and samples back WINTER LAKEKEEPERS • Teamed up with ice anglers • Funded by Alberta Ecotrust • Piloted early 2019 at 10 lakes • Focus on nutrient and oxygen levels WHY STUDY LAKES IN WINTER? • Important processes continue under ice • Nutrients released and released and captured • Algae blooms still a part of this system WHY STUDY LAKES IN WINTER? • Oxygen produced and consumed, becomes a limited resource. • It’s kind of important Winterkill at Crimson Lake, 2018 (Edmonton Journal) OXYGEN TOLERANCE IN ALBERTA FISH (Barton and Taylor 1995) Sensitive: all salmonids, longnose sucker, >2 mg/L DO burbot Intermediate: all cyprinids except fathead minnow, walleye, white sucker, brook 1-2 mg/L DO stickleback and goldeye) Tolerant: includes fathead minnow, northern pike and yellow perch) < 1 mg/L DO WHAT INCREASES A LAKE’S RISK OF ANOXIA? • Shallow depth • Eutrophication • Longer ice cover • Snow cover Caters News Agency 2014 What they measured: What they measured: • Temperature and dissolved oxygen profiles What they measured: • Temperature and dissolved oxygen profiles • Air temperature What they measured: • Temperature and dissolved oxygen profiles • Air temperature • Snow depth What they measured: • Temperature and dissolved oxygen profiles • Air temperature • Snow depth • Ice depth What they measured: • Temperature and dissolved oxygen profiles • Air