REDWALL by CAROL OTIS HURST

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loamhedge by Brian Jacques Quotes from Loamhedge

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loamhedge by Brian Jacques Quotes from Loamhedge. “When the sun sets like fire, I will think of you, when the moon casts its light, I'll remember, too, if a soft rain falls gently, I'll stand in this place, recalling the last time, I saw your kind face. Good fortune go with you, to your journey's end, let the waters run calmly, for you, my dear friend.” ― Brian Jacques, quote from Loamhedge. “The crafty otter produced a flat pebble from his helmet, spat on one side of it, and held it up for the bird to see. 'Right, I'll spin ye. Dry side, I win, wet side, you lose. Good?' The honey buzzard nodded eagerly. Buteo's keen eyes watched every spin of the stone until it clacked down flat on the deck. Garfo grinned from ear to ear. 'Wet side! You lose!” ― Brian Jacques, quote from Loamhedge. “Friendship is the greatest gift one can give to another.” ― Brian Jacques, quote from Loamhedge. “When weary day does shed its light, I rest my head and dream, I ride the great dark bird of night, so tranquil and serene. Then I can touch the moon afar, which smiles up in the sky, and steal a twinkle from each star, as we go winging by. We’ll fly the night to dawning light, and wait ’til dark has ceased, to marvel at the wondrous sight, of sunrise in the east. So slumber on, my little one, float soft as thistledown, and wake to see when night is done, fair morning’s golden gown.” ― Brian Jacques, quote from Loamhedge. -

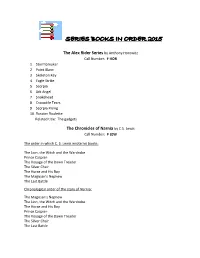

The Redwall Adventures by Brian Jacques Call Number: F JAC

SERIES BOOKS IN ORDER 2015 The Alex Rider Series by Anthony Horowitz Call Number: F HOR 1. Stormbreaker 2. Point Blanc 3. Skeleton Key 4. Eagle Strike 5. Scorpia 6. Ark Angel 7. Snakehead 8. Crocodile Tears 9. Scorpia Rising 10. Russian Roulette Related title: The gadgets The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis Call Number: F LEW The order in which C. S. Lewis wrote his books: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Prince Caspian The Voyage of the Dawn Treader The Silver Chair The Horse and His Boy The Magician’s Nephew The Last Battle Chronological order of the story of Narnia: The Magician’s Nephew The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe The Horse and His Boy Prince Caspian The Voyage of the Dawn Treader The Silver Chair The Last Battle The Dragonback Adventure Series by Timothy Zahn Call Number: F ZAH 1. Dragon and Thief 2. Dragon and Soldier 3. Dragon and Slave 4. Dragon and Herdsman 5. Dragon and Judge 6. Dragon and Liberator The Dragonkeeper Chronicles by Donita K. Paul Call Number: F PAU 1. Dragonspell 2. Dragonquest 3. Dragonknight 4. Dragonfire 5. Dragonlight The Dreamhouse Kings Series by Robert Liparulo Call Number: F LIP 1. House of Dark Shadows 2. Watcher in the Woods 3. Gatekeepers 4. Timescape 5. Whirlwind 6. Frenzy The Guardians of Ga’Hoole Series by Kathryn Lasky Call Number: F LAS 1. The Capture 2. The Journey 3. The Rescue 4. The Siege 5. The Shattering 6. The Burning 7. The Hatchling 8. The Outcast 9. The First Collier 10. -

Publication Order

Publication Order young mouse warrior Martin The Legend of Luke (1999) vows to end the evil beast's Addressing some of the mysteries behind the Abbey's Redwall (1986) plundering and killing. early years, this book tells the tale of two quests: that As the inhabitants of Redwall The Bellmaker (1994) of a son, Martin the Warrior, to find his father and that Abbey bask in the glorious of a father to avenge the murder Summer of the Late Rose, all is More than four seasons have of his beloved wife. Brian quiet and peaceful. But things are passed since Mariel the Jacques' skillful narrative is told not as they seem. Cluny the Warriormouse and the rogue in three parts, interweaving the Scourge--the evil one-eyed rat mouse, Dandin, set off from stories of father and son. warlord, is preparing to fight a Redwall in search of adventure, bloody battle for the ownership of and Joseph the Bellmaker is Lord Brocktree (2000) worried. Where is his beloved Redwall. Dotti, a brazen young haremaid, daughter? Can he find his and the badger Lord Brocktree, a Mossflower (1988) daughter before the dreaded Foxwolf, Urgan Nagru, fearsome warrior embark on a plunders the kingdom of Southsward? The clever and greedy wildcat Tsarmina rules all perilous journey. These most Mossflower Woods with an iron paw. Brave mouse Outcast of Redwall (1995) unlikely of companions search Martin, quick-talking mouse thief Gonff, and Kinny for Salamadastron which is under siege by the vicious the mole resolve to end her tyrannical rule, setting off When ferret Swartt Sixclaw and his badger arch enemy wildcat Ungatt Trunn and his infamous Blue Hordes. -

Marlfox, Brian Jacques

Marlfox, Brian Jacques DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1qEagpj http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marlfox Queen Silth rules Castle Marl from behind the curtains of her palanquin. Greedy and vain, she has sent her six children into the world to plunder treasure. Stealth and cunning are the traits of the Marlfox. Known only in Redwall country by legend, they are said to able to appear and disappear by magic. When the strange creatures begin to appear in Mossflower Woods, it is clear that evil is abroad. A kidnapping and a cunning raid to steal the beautiful Redwall tapestry confirm the worst; Redwall is under threat! Three young friends, fated by the prophecy of Martin the Warrior, pursue the villains in a quest of daring, courage and wit to return the beloved tapestry to its home. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/af7g5fm09S http://bit.ly/1xRgKJr Outcast Of Redwall , Brian Jacques, Jan 25, 2011, Juvenile Fiction, 368 pages. Ferret Swartt Sixclaw and badger Sunflash the Mace are arch enemies who have sworn a pledge of death upon each other. Meanwhile, the Abbess of Redwall has banished a young. Mattimeo , Brian Jacques, Jul 31, 2012, Juvenile Fiction, 448 pages. Slagar the Fox is bent on revenge - and determined to bring death and destruction to Redwall Abbey. Gathering his evil band around him, Slagar plots to strike at the heart of. The Sable Quean , Brian Jacques, Feb 23, 2010, Fiction, 368 pages. Buckler the hare, Blademaster of the Long Patrol, must save the youngsters of Redwall Abbey-kidnapped by the vile Vilaya the Sable Quean-and stop the villain's conquest of. -

Will Love 200+ Chapter Books Your Kids Will Love

200+ Chapter Books Your Kids Will Love 200+ Chapter Books Your Kids Will Love Are you looking for chapter book ideas to share with your children? Maybe your child is a reluctant reader and you're looking for just the right chapter books to spark her interest in reading. Or maybe your child reads voraciously and devours reading material so quickly that you can't seem to keep up with his literary appetite. Or maybe you're looking for a wonderful series for family read-aloud time and need some new suggestions. In any case, you can never have too many book recommendations when it's time for a trip to the library! The lists that follow have been carefully selected for your family. All you have to do is pick a series, print the list, and head over to your local library. Let the reading fun begin! Table of Contents A to Z Mysteries ................................................................................................................. 3 Encyclopedia Brown .......................................................................................................... 4 Gone-Away Lake ................................................................................................................ 5 Gooney Bird Greene .......................................................................................................... 6 The Green Ember .............................................................................................................. 7 Hank the Cowdog .......................................................................................................... -

Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) by Libba Bray 1

3. Sirensong Young Adult Series List Great and Terrible Beauty June 2012 (By Author) By Libba Bray 1. A Great and Terrible Beauty Chains 2. Rebel Angels By Laurie Anderson 3. The Sweet Far Thing 1. Chains: Seeds of America 2. Forge The Faerie Wars Chronicles By Herbie Brennan Darkest Powers 1. Faerie Wars By Kelly Armstrong 2. Purple Emperor 1. The Summoning 3. Ruler of the Realm 2. The Awakening 4. Faerie Lord 3. The Reckoning The Gideon Trilogy Otherworld Series By Linda Buckley-Archer By Kelley Armstrong 1. The Time Travelers 1. Bitten 2. The Time Thief 2. Stolen 3. The Time Quake 3. Dime Store Magic 4. Industrial Magic Princess Diaries 5. Haunted By Meg Cabot 6. Broken 1. Princess Diaries 7. No Humans Involved 2. Princess in the Spotlight 8. Personal Demon 3. Princess in Love 9. Living with the dead 4. Princess in Waiting 10. Frostbitten 41/2. Project Princess 11. Waking the Witch 5. Princess in Pink 6. Princess in Training The Looking Glass Wars 61/2. The Princess Present By Frank Bennor 7. Party Princess 1. The Looking Glass Wars 71/2. Sweet Sixteen Princess 2. Seeing Redd 73/4. Valentine Princess 3. Arch Enemy 8. Princess on the Brink 9. Princess Mia Grey Griffin 10. Forever Princess By Derek Benz 11. Princess Lessons 1. Revenge of the Shadow King 12. Holiday Princess 2. Rise of the Black Wolf 13. Perfect Princess 3. Fall of the Templar Morganville Vampire A Modern Faerie Tale By Rachel Caine By Holly Black 1. Glass Houses 1. -

Mossflower: a Tale from Redwall Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MOSSFLOWER: A TALE FROM REDWALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian Jacques,Gary Chalk | 432 pages | 30 Sep 2002 | Penguin Young Readers Group | 9780142302385 | English | New York, NY, United States Mossflower: A Tale from Redwall PDF Book The Sable Quean. Condition: Bon. It reminds me sometimes wehn presenting something to other people, it takes courage becaue i am not that kind of person who like to talk openly with others. Book is in good condition with no missing pages, no damage or soiling and tight spine. The Rogue Crew. Trivia About Mossflower Redwa Making up little ditties before, during and after each adventure, the joyful and musical little mouse was much more adorable and interesting than his companion Martin. The is one of the books that I love to curl up and dive into, and it's prime material for getting lost in. Condition: Good. By: Brian Jacques. Gary Chalk. Mossflower Redwall Published by -. I also tend to enjoy the prequel stories because of Martin who has a pretty fascinating life story and ultimately drives the entire series through his spirit which serves as a symbol of goodness. Jun 08, Abbie rated it it was amazing Shelves: fantasy. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. About the Book. Regardless, this series is a win for me thus far. The Fall of the Readers. High Rhulain. Continuing my new purpose of writing about books that influenced me as a child, I had to get started on Mossflower. At one point, a pact of leaders formed a group called Corim, a sort of alliance between many creatures to protect the land. -

The Rogue Crew: a Tale of Redwall Ebook Free Download

THE ROGUE CREW: A TALE OF REDWALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian Jacques | 400 pages | 03 May 2011 | Philomel Books | 9780399254161 | English | New York, NY, United States The Rogue Crew: A Tale of Redwall PDF Book Who will come to the aid of Redwall Abbey? Buy with confidence, excellent customer service!. Maybe it's just because I'm young, but these books are so hard to put down. A book set in an abbey, cloister, monastery, vicarage or convent. Editorial review of Redwall. More information about this seller Contact this seller Later, Swiffo is killed near the Abbey by Ketral Vane , a vermin fox equipped with poison darts. This final book was one of the best of the series, as it doesn't bounce around or have frivolous poems throughout. Also, a main waterway is the River Moss. In the list above, these books are organized according to the period of the main narrative, rather than by the period of the framing story which is almost always after the construction of Redwall. Views Read Edit View history. Works by Brian Jacques. That is bad. The characters aren't as compelling as in the first several Redwall adventures and the narrative isn't as poignant, but I'll always cherish this series as foundational to my love of reading. I started with Outcast of Redwall last year and I honestly felt like that was a trial to get through. Miggory is amazing. Cover has some rubbing and edge wear. But it's from these distant kin that Uggo learns of the peril facing Redwall: Razzid has heard about the abbey, and is on the move to conquer the place and murder its citizens. -

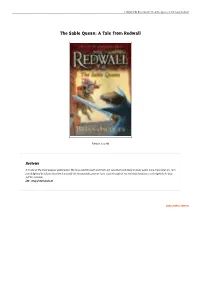

Read Ebook # the Sable Quean: a Tale from Redwall

L3XQVYHEMLRS » eBook \ The Sable Quean: A Tale from Redwall The Sable Quean: A Tale from Redwall Filesize: 3.01 MB Reviews It in one of the most popular publication. We have read through and that i am sure that i will likely to study again once more later on. I am just delighted to tell you that this is actually the finest publication we have read through in my individual existence and might be he best pdf for actually. (Mr. Cloyd Schmidt II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA F0VZAXUHZCNG eBook < The Sable Quean: A Tale from Redwall THE SABLE QUEAN: A TALE FROM REDWALL To read The Sable Quean: A Tale from Redwall eBook, remember to access the web link beneath and save the document or have accessibility to additional information that are related to THE SABLE QUEAN: A TALE FROM REDWALL ebook. Philomel. 1 Cloth(s), 2010. hard. Book Condition: New. The last Redwall novel published during Brian Jacques's lifetime (followed only by the posthumous The Rogue Crew), this adventure for readers 9 and up is one of the chronicles' most unforgettable. Vilaya the Sable Quean, devious ruler of hordes of vermin, intends to conquer Redwall Abbey, and when the Dibbuns at the abbey begin to go missing, her plan is revealed. Will the creatures of Redwall risk their home and all of Mossflower Wood to save their precious young ones? Perhaps Buckler the hare, Blademaster of the Long Patrol, can save the day, especially since he has a score of his own to settle. At the same time, Vilaya may have her hands full, as the Dibbuns of Redwall are not as helpless as they appear. -

Salamandastron Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SALAMANDASTRON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian Jacques | 356 pages | 01 Apr 1996 | Time Warner International | 9780441000319 | English | New York, United States Salamandastron PDF Book A struggle follows and Swinkee loses his tail. They sneak inside the Abbey and are caught by the otter Thrugg. Ask a question Ask a question If you would like to share feedback with us about pricing, delivery or other customer service issues, please contact customer service directly. Sickness accompanied with high fever, weakness, and chills. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Grandmother of Burrem. Ferahgo sends the trackers on the journey again. So if you find a current lower price from an online retailer on an identical, in-stock product, tell us and we'll match it. Male wren. Husband of Loambudd, father of Urthhound, grandfather of Urthwyte and Urthstripe. The young squirrel is surprised by Friar Bellows , who is shocked to find Samkim near the dead Brother. Surrounded by tall walls. Urthstripe the Strong, a wise old badger, leads the animals of the great fortress of Salamandastron and Redwall Abbey against the weasel Ferahgo the Assassin and his corps of vermin. Fantasy book series. The last interior artist was Sean Rubin. Stealthy and mysterious, they are Chronological Order :. August 23, Urthstripe the Strong, a wise old badger, leads the animals of the great fortress of Salamandastron and Redwall Abbey against the weasel Ferahgo the Assassin and his corps of vermin. Later he arrives to Salamandastron, bringing food with him. Books in the Redwall Chronicles, by Brian Jacques. As a general rule though, characters tend to "epitomize their class origins", rarely rising above them. -

Martin's Journey to Sainthood in Brian Jacques's Redwall Series

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 From Wanderer to Warrior: Martin's Journey to Sainthood in Brian Jacques's Redwall Series Marie A. Bliemeister Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bliemeister, Marie A., "From Wanderer to Warrior: Martin's Journey to Sainthood in Brian Jacques's Redwall Series" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1930. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1930 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM WANDERER TO WARRIOR: MARTIN’S JOURNEY TO SAINTHOOD IN BRIAN JACQUES’S REDWALL SERIES by MARIE BLIEMEISTER (Under the direction of Richard Flynn) ABSTRACT Children’s fantasy series have been set in the Medieval Era, a way to explore contemporary themes. This use of the Medieval Era is known as medievalism, where authors can explore contemporary issues by comparing them to the past (Bradford 3). Brian Jacques, the author of the popular children’s series Redwall, uses many aspects of the Medieval Era such as prophecies, glory, and battle, and visions or dreams to effectively spin a good yarn while commenting on the religious development of England in the late twentieth century. English moral was down due to the devastation of World War Two and religious ideals were facing rebuke by the rising notions of secularism. -

Download Doc / Loamhedge (Redwall Series Book

08X3NAJOAEWQ » eBook » Loamhedge (Redwall Series Book 16) Read eBook LOAMHEDGE (REDWALL SERIES BOOK 16) Ace Books, New York, 2004. Softcover (Mass Market). Condition: New. First Thus. 333 pages. Book in new condition--from my store inventory. This is the16th book in the Redwall series--so, a wonderful swashbuckling adventure series for the child who needs to practice reading. They are very addictive. Loamhedge is a deserted abbey, but when it becomes clear that it might contain the cure for wheel-chair bound Martha, two old warriors and three young rebels determine to go on a quest to... Download PDF Loamhedge (Redwall Series Book 16) Authored by Jacques, Brian Released at 2004 Filesize: 9.28 MB Reviews Extensive guideline! Its this sort of very good go through. I have got read and i am condent that i will gonna read through once more once more in the future. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. -- Joana Champlin This book may be worth buying. I have read and i am condent that i am going to planning to go through once more once again in the future. Its been written in an exceptionally easy way and it is simply soon after i nished reading this publication in which actually altered me, modify the way i believe. -- Faye Shanahan TERMS | DMCA GFS02J4E0WUK » Doc » Loamhedge (Redwall Series Book 16) Related Books The Wolf Who Wanted to Change His Color My Little Picture Book Barabbas Goes Free: The Story of the Release of Barabbas Matthew 27:15-26, Mark 15:6-15, Luke 23:13-25, and John 18:20 for Children If I Were You (Science Fiction & Fantasy Short Stories Collection) (English and English Edition) Zombie Books for Kids - Picture Books for Kids: Ghost Stories, Villagers, Monsters Zombie Invasion Apocalypse Stories for Kids: 2 in 1 Boxed Set for Kids MY FIRST BOOK OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR 3 IN 1 NOUNS ADJECTIVES VERBS AGE 5+.