Redefining Gentrification in Chicago's West Loop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1115 W Fulton Brochure

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS SPACE Overview 4 Ground Level 6 Second Level 7 Third Level 8 Interior Renderings 10 NEIGHBORHOOD Map 16 The West Loop 18 Fulton Market 20 Access 22 NEIGHBORS Offi ces 24 Dining 28 Hospitality 32 Entertainment & Arts 33 Residents 34 Demographics 35 About McCaffery Interests 37 THE SPACE 1115 W. Fulton Market offers a rare opportunity: in the heart of the Fulton Market District, 37,500 square feet available on 3 fl oors. 4 5 THE SPACE Ground Level THE SPACE Second Level 6 7 THE SPACE Third Level THE SPACE Elevations 8 9 THE SPACE Interior Renderings 10 11 12 13 14 15 As A 16 hla n N ASHLAND AVE d [proposed] Coming soon Other Financial Hotel Health Dining&Drinking Retail TCF Bank All RiseBrewing C W ARBOR PL W ARBOR obra Lounge P i tc hf o rk M U R us oom 1520 i c ni F est iv al o Billy Goat Tavern N OGDEN AVE n Par Subway N JUSTINE ST Dunkin’ Donuts Harold’s Chicken Shack k Pet CarePlu Gunzo’s Sport s W S LAFLIN ST W ASHINGTON BLVD N LAFLIN ST Th Transit Ni Transit e Min W CARROLL AVE W CARROLL e M W FU C G g hil reen Beginning htclu us dca i c H N BISHIOP ST b r a e ll L TON ST Rush Presbyterian s Kaiser Tiger Palace Grill Bad AxeThrowin N LOOMIS ST N LOOMIS ST West Loop g S LOOMIS ST Athletic Club Johnny’s EBER Icehouse McDonald’sldd’s S M Bottom Lounge OO RE Galls Service Center Gyu-Kaku Lou Deal Alice Padrul Bridal Loft on Lakeakeake Madison Vine Wines Concierge Flowers Bespoke Cuisine Marathon GasMMarath Custom By Lamar CrossFit 312 Randolph St Market Viaggio Ristorante Elske GoodDog Blue Plate Catering WestEnd The -

Reform and Renewal: Improving Mass Transit in a New Economy

Reform and Renewal: Improving Mass Transit in a New Economy President's 2012 Budget Recommendations CTA FY12 Budget Chicago Transit Board Terry Peterson, Chairman Appointed by: Mayor, City of Chicago Jacquelyne Grimshaw, Vice Chairman Appointed by: Governor, State of Illinois John Bouman Appointed by: Governor, State of Illinois Kathryn McClain Appointed by: Governor, State of Illinois Charles E. Robinson Appointed by: Mayor, City of Chicago Alejandro Silva Appointed by: Mayor, City of Chicago Forrest Claypool, President transitchicago.com 1-888-YOUR-CTA CTA FY12 Budget Table of Contents Letter from the President ........................................................................................................................................ 1 CTA Organizational Chart ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... 5 2011 Operating Budget Performance 2011 Operating Budget Performance Summary ........................................................................................ 17 2011 Operating Budget Schedule ..................................................................................................................... 23 President’s 2012 Proposed Operating Budget President’s 2012 Proposed Operating Budget Summary ...................................................................... -

Developed by Contents

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS NEIGHBORHOOD The West Loop 06 Fulton Market 08 Map 10 Access 12 NEIGHBORS Offi ces 14 Dining 18 Hospitality 22 Entertainment & Arts 23 Residents 24 Demographics 25 SPACE Overview 26 First Level Retail 28 About McCaffery Interests 29 3 4 5 THE WEST LOOP Once a Marketplace, Always a Marketplace Bounded by Ashland Avenue to the West, the Chicago River to the East, the Eisenhower Expressway to the South and Grand Avenue to the North, the West Loop has played a key role in making Chicago an economic powerhouse. Originally home to the city’s bustling wholesale market district, several of the West Loop’s charismatic warehouses continue to market and distribute food goods today, while neighboring thoroughfares are being revitalized to refl ect and foster the urban life, culture and energy for which this historic area is known. 6 7 FULTON MARKET Dynamic Day & Night Destination At the heart of the West Loop is Fulton Market. The proximity of this quiet, westbound avenue to the city’s nineteenth century rail and stock yards positioned it as a vital hub of Chicago’s growing food enterprises. Wide sidewalks increase walkability and offer opportunities for outdoor dining, parklets and window shopping. Nearby public transportation, bike- sharing stations, and multiple interstate connections makes the area highly accessible by foot, train, bike or car. Just blocks off of Randolph Street’s in-demand “Restaurant Row” and minutes from Chicago’s hip Greektown neighborhood, Fulton Market is at the center of this 24/7 district. ©John8 Joh -

Designated Historic and Natural Resources Within the I&M Canal

Designated historic and natural resources within the I&M Canal National Heritage Corridor Federal Designations National Cemeteries • Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery National Heritage Areas • Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area National Historic Landmarks • Adler Planetarium (Chicago, Cook County) • Auditorium Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Carson, Pirie, Scott, and Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Chicago Board of Trade Building (LaSalle Street, Chicago, Cook County) • Depriest, Oscar Stanton, House (Chicago, Cook County) • Du Sable, Jean Baptiste Point, Homesite (Chicago, Cook County) • Glessner, John H., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Hegeler-Carus Mansion (LaSalle, LaSalle County) • Hull House (Chicago, Cook County) • Illinois & Michigan Canal Locks and Towpath (Will County) • Leiter II Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marquette Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marshall Field Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Mazon Creek Fossil Beds (Grundy County) • Old Kaskaskia Village (LaSalle County) • Old Stone Gate, Chicago Union Stockyards (Chicago, Cook County) • Orchestra Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Pullman Historic District (Chicago, Cook County) • Reliance Building, (Chicago, Cook County) • Rookery Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Shedd Aquarium (Chicago, Cook County) • South Dearborn Street-Printing House Row North (Chicago, Cook County) • S. R. Crown Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Starved Rock (LaSalle County) • Wells-Barnettm Ida B., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Williams, Daniel Hale, House (Chicago, Cook County) National Register of Historic Places Cook County • Abraham Groesbeck House, 1304 W. Washington Blvd. (Chicago) • Adler Planetarium, 1300 S. Lake Shore Dr., (Chicago) • American Book Company Building, 320-334 E. Cermak Road (Chicago) • A. M. Rothschild & Company Store, 333 S. State St. (Chicago) • Armour Square, Bounded by W 33rd St., W 34th Place, S. Wells Ave. and S. -

Neighborhood Plan West Loop

West Loop Neighborhood Plan Prepared by: Neighbors of West Loop Chicago, IL August, 2018 West Loop Neighborhood Plan In 2013, an effort was initiated to increase collaboration among residents across the four wards of the transforming West Loop. The Fulton River District Association (FRDA), a neighborhood group located in the northeast portion of the West Loop, looked beyond its boundaries to engage nearby volunteers. FRDA worked with residents that were participating in other community organizations like park advisory councils (PACs), Community Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS), local school councils, and other positive community organizations. In January of 2014, the Fulton River District Association became Neighbors of West Loop and expanded its geographic reach to include all of the West Loop as we know it today. Neighbors of West Loop (NoWL) is a neighborhood organization comprised of West Loop residents who bring together others in the area who want to make a positive impact on our vibrant community. We are a non-profit organization, supported by our membership and other West Loop residents who volunteer their time to benefit the organization. The organization is founded on transparency and welcomes anyone who wants to make a difference at the local level. The positions that we establish and the initiatives that we promote are aligned with the feedback that we receive from the community. Our goal is to empower residents who wish to volunteer their time for the West Loop. We believe in transparency and the idea that every resident should have the opportunity to be informed and to be heard on issues that affect their community. -

Available Production Area 222 N

AIR CONDITIONED AVAILABLE PRODUCTION AREA 222 N. Maplewood Ave. Chicago, IL New opportunity in Chicago’s coveted Kinzie Corridor Neighborhood MIKE SENNER TEL: +1 847 698 8234 [email protected] THOMAS VOLINI TEL: +1 312 612 5949 [email protected] ALEX KRITT TEL: +1 847 698 8537 [email protected] Rare flex opportunity in Chicago’s most desirable service location Size 68,000 SF Office Approximately 7,000 SF Total building size 68,000 SF Landsite Approximately .95 acres Power 2000 Amp/480 volt Construction Concrete and brick Loading Three (3) interior docks Three (3) drive in doors Parking 25+ parking spaces HVAC The production areas are fully air conditioned Visibility Excellent visibility on Lake Street and Maplewood Avenue Applications High end manufacturing, flex, showroom, and office Lease Rate $7.50 net Sale Price Subject to Offer Possession July 1, 2020 Taxes $74,449 estimated for 2018 payable 2019 Excellent proximity to Chicago’s central business district and all Location major expressways. Adjacent to the city’s most affluent submar- kets with an abundant, energetic labor force. 19 Irving Park Rd PORTAGE PARK NORTH CENTER N Broadway Addison St AVONDALE Clark St Belmont Ave LAKEVIEW Laramie Ave Laramie Central Ave Central Austin Ave Austin Milwaukee Ave Lincoln Ave Elston Ave 41 Southport Ave Sheeld Ave Ashland Ave Diversey Ave Halsted St Clybourn Ave BELMONT CRAGIN Fullerton Ave LOGAN SQUARE 50 HERMOSA LINCOLN PARK Lincoln Park Zoo Central Park Ave Central Armitage Ave Humboldt Blvd California Ave California Western Ave Western Kostner Ave Kostner Damen Ave Kedzie Ave Kedzie Pulaski Rd 64 North Ave 94 Grand Ave WICKER PARK HUMBOLDT St Larabee 222 N. -

Developed by Contents

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS SPACE Overview 4 Ground Level 6 Second Level 7 Third Level 8 Interior Renderings 10 NEIGHBORHOOD Map 16 The West Loop 18 Fulton Market 20 Access 22 NEIGHBORS Offi ces 24 Dining 28 Hospitality 32 Entertainment & Arts 33 Residents 34 Demographics 35 About McCaffery Interests 37 THE SPACE 1115 W. Fulton Market offers a rare opportunity: in the heart of the Fulton Market District, 37,500 square feet available on 3 fl oors. 4 5 THE SPACE Ground Level THE SPACE Second Level LEASED 6 7 THE SPACE Third Level THE SPACE Elevations 8 9 THE SPACE Interior Renderings 10 11 12 13 14 15 As A 16 hla n N ASHLAND AVE d [proposed] Coming soon Other Financial Hotel Health Dining&Drinking Retail TCF Bank All RiseBrewing C W ARBOR PL W ARBOR obra Lounge P i tc hf o rk M U R us oom 1520 i c ni F est iv al o Billy Goat Tavern N OGDEN AVE n Par Subway N JUSTINE ST Dunkin’ Donuts Harold’s Chicken Shack k Pet CarePlu Gunzo’s Sport s W S LAFLIN ST W ASHINGTON BLVD N LAFLIN ST Th Transit Ni Transit e Min W CARROLL AVE W CARROLL e M W FU C G g hil reen Beginning htclu us dca i c H N BISHIOP ST b r a e ll L TON ST Rush Presbyterian s Kaiser Tiger Belly Q Palace Grill Bad AxeThrowin N LOOMIS ST N LOOMIS ST West Loop g S LOOMIS ST Athletic Club Johnny’s EBER Icehouse McDonald’sldd’s S M Bottom Lounge OO RE Galls Service Center Gyu-Kaku Lou Deal Alice Padrul Bridal Loft on Lakeakeake Madison Vine Wines Concierge Flowers Bespoke Cuisine Marathon GasMMarath Custom By Lamar CrossFit 312 Randolph St Market Viaggio Ristorante Elske GoodDog Blue Plate Catering -

MOVE-IN READY SPACE in FULTON MARKET up to 55,000 RSF AVAILABLE for LEASE DIVISIBLE to 7,500 RSF Here

MOVE-IN READY SPACE IN FULTON MARKET UP TO 55,000 RSF AVAILABLE FOR LEASE DIVISIBLE TO 7,500 RSF here now DEVELOPER: LEASING: building features • Move-in ready space in Fulton Market available immediately • Up to 55,000 SF available, divisible to 7,500 SF • Located on the corner of Randolph and Racine • Up to 50 parking spaces • Short-term leases available up to 5 years • Rent: low $20s gross • Electricity included • Furniture available fulton market Fulton Market district has always been a self-starter. Its industrial grit and legacy of entrepreneurship have set the stage anew for boundary-pushing office users, restaurants and retailers. It’s Chicago’s most sought-after neighborhood. 14,200% POPULATION GROWTH IN FULTON MARKET DISTRICT SINCE 2000 +3M SF OF NEW OFFICE SPACE IN DEVELOPMENT IN THE FULTON MARKET 4,200 RESIDENTIAL UNITS IN PIPELINE $42M IN AREA INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENT COMMITTED BY THE CITY 72% INCREASE IN RIDERSHIP SINCE CTA MORGAN STATION OPENING IN 2012 845+ HOTEL KEYS: SOHO HOUSE, HOXTON, ACE, NOBU, EQUINOX KINZIE KINZIE BLIND PIG 450 N. MORGAN DISTILLERY 360 N. GREEN FOR SALE MORGAN NEALEY MANUFACTURING FOODS ADM MILLING CARROL CARROL 330 N. GREEN STUMPTOWN NEALEY HWH THINKUBATOR COFFEE GR333N W MAZEL LINDA FOODS FULTON FOUR ROASTERS Y N A METALS WARREN CORNERS MARKET D 90 A E PROJECTS AD CONCEPT /HWY N I DYSON Y CIN L NGAMON GLASSDOOR MA PEORI RA CARPENTER GREEN AF HALSTE SA FOUR STAR ABERDEE MORGAN 994 LAFLIN L 4 SKENDER FOODS P SA IGNITE BAUSCHER NEALEY PUNCH BOWL SOCIAL CLIMATE MATERIALS PIZZERIA HEPP TIME OUT FOODS ELIZABETH MARKETING DEL MERCATO SHOWROOM MARKET CDT DEAN & DELUCA AESO YA FULTON FULTON AKE S TER BOUTIQUE CHICAGO ASPEN FOODS TA JUPITER PARTY BITES ROIS RAMEN T OUTPOST CEMI PUEBLA 1325 W. -

Fulton Market District Chicago 900 West 900 Block of West Randolph Street Project Overview

900 WEST FULTON MARKET DISTRICT CHICAGO 900 WEST 900 BLOCK OF WEST RANDOLPH STREET PROJECT OVERVIEW THE MOST DYNAMIC AND CENTRALLY LOCATED FULTON MARKET DESTINATION TOTAL OF 45,000 RENTABLE SQUARE FEET OF RETAIL COTENANCY AVAILABLE WITH 45,000 SQUARE FEET OF OFFICE ABOVE. FUTURE PHASE 2 TO INCLUDE LUXURY APARTMENTS FULL REDEVELOPMENT OF MULTIPLE BUILDINGS AT THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF WEST RANDOLPH AND NORTH SANGAMON STREETS MULTIPLE DEMISING OPTIONS FASHION AND RESTAURANTS DESIRED DRAMATIC CEILING HEIGHTS UP TO 14’-6” ABILITY FOR OUTDOOR SEATING IMMEDIATE DELIVERY 900 WEST MARKET OVERVIEW FULTON MARKET DISTRICT IS THE FUTURE OF CHICAGO FASHION, ENTERTAINMENT AND NIGHTLIFE • ANTHROPOLOGIE • SOHO HOUSE • EQUINOX HOTEL & SPA • AESOP • ACE HOTEL • PUNCH BOWL SOCIAL • FREE PEOPLE • NOBU HOTEL • STARBUCKS RESERVE RANDOLPH STREET • BLVDier • HOXTON HOTEL • BILLY REID • M2057 BY MARIE PINTO • KIT & ACE THE TRENDSETTING HEART OF FULTON MARKET DISTRICT IS HOME TO ONE OF THE HOTTEST INTERNATIONAL THE REGION FOR 25 DINING SCENES WITH INTERNATIONALLY ACCLAIMED RESTAURANTS YEARS AND COUNTING • AVEC • GRACE • NEXT • THE AVIARY • LA SIRENA CLANDESTINA • DUCK DUCK GOAT • BELLY Q • MAUDE’S LIQUOR BAR • LENA BRAVA • BLACKBIRD • NELLCOTE • NOSH & BOOZE • CITY WINERY • PUBLICAN QUALITY MEATS • SWIFT & SONS • DE CERO • RM CHAMPAGNE SALON • GIRL & THE GOAT • AU CHEVAL • MOMOTARO • LITTLE GOAT • WONFUN & 2FUN 900 CHINESE WEST MARKET OVERVIEW THEN 2017 & BEYOND 2005 DEMOGRAPHICS DEMOGRAPHIC GROWTH OVER WITHIN ONE MILE THE NEXT 12 MONTHS A REGIONAL MARKET POPULATION -

Haddix Thesis Finalpdf.Pdf (5.806Mb)

SAVORING PLACE: PROTECTING CHICAGO’S SENSE OF PLACE BY PRESERVING ITS LEGACY RESTAURANTS. LEIGH A. HADDIX 2018 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: SAVORING PLACE: PROTECTING CHICAGO’S SENSE OF PLACE BY PRESERVING ITS LEGACY RESTAURANTS Degree Candidate: Leigh Haddix Degree and Year: Master of Arts in Historic Preservation, 2018 Thesis Directed By: Betsy Bradley Welch Center for Graduate and Professional Studies Goucher College Humanist geographer Edward G. Relph in Place and Placelessness conceptualized a vision of place using a phenomenological approach based upon how humans experience place. Relph’s three main place components include Setting, Activity and Meaning, and considering resources in this manner can reframe preservation thought. Viewing place through Relph’s lens makes for a more holistic vision, that can shape what and how we preserve. A Relphian framework also provides a useful practice theory for preservationists to expand our notion of who performs preservation and how we evaluate sense of place. Small businesses are neighborhood anchors, and historic restaurants play a particularly social and experiential role. Tangible and intangible cultural heritage must be evaluated holistically when focusing preservation actions upon businesses such as historic restaurants. Legacy restaurants are place makers and visible markers of the layers of history within a place. They convey social history and foodways and act as expressions of the intangible cultural heritage that lends character to place. Change is a part of place; cuisine, the history of a place, and historic businesses do not remain static. Just as legacy business owners have had to be agile and adaptable to remain relevant and successful, historic preservation may work most effectively when it too is agile and adaptable in response to change. -

Developed by Contents

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS SPACE Overview 4 Ground Level 6 Second Level 7 Third Level 8 Interior Photos 10 NEIGHBORHOOD The West Loop 18 Fulton Market 20 Access 22 NEIGHBORS Offices 24 Design 28 Dining 30 Hospitality 34 Entertainment & Arts 35 Residents 36 Demographics 37 About McCaffery Interests 39 THE SPACE 1115 W. Fulton Market offers a rare opportunity: in the heart of the Fulton Market District, 37,500 square feet available on 3 floors. 4 5 THE SPACE Ground Level THE SPACE Second Level 6 7 THE SPACE Third Level THE SPACE Elevations 8 9 THE SPACE First Level 10 11 THE SPACE First Level 12 13 THE SPACE Second Level 14 15 THE SPACE Second Level 16 17 THE WEST LOOP Once a Marketplace, Always a Marketplace Bounded by Ashland Avenue to the West, the Chicago River to the East, the Eisenhower Expressway to the South and Grand Avenue to the North, the West Loop has played a key role in making Chicago an economic powerhouse. Originally home to the city’s bustling wholesale market district, several of the West Loop’s charismatic warehouses continue to market and distribute food goods today, while neighboring thoroughfares are being revitalized to reflect and foster the urban life, culture and energy for which this historic area is known. 18 19 FULTON MARKET Dynamic Day & Night Destination At the heart of the West Loop is Fulton Market. The proximity of this quiet, westbound avenue to the city’s nineteenth century rail and stock yards positioned it as a vital hub of Chicago’s growing food enterprises. -

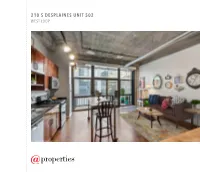

210 S Desplaines Unit

210 S DESPLAINES UNIT 502 WEST LOOP ROOM DIMENSIONS BEAUTIFUL WEST LOOP LOFT LIVING ROOM : 19' × 10' KITCHEN : 19' × 8' PRIMARY BEDROOM : 14' × 13' *Luxury Living at The Edge Lofts & Towers. This bright sunny upgraded unit is part FOYER : 5' × 4' of the original loft portion of the building with high concrete ceilings, exposed PRIVATE BALCONY : 14' × 4' ductwork and floor to ceiling windows with a huge balcony & city views. WALK IN CLOSET : 8' × 2' *Features include real refinished hardwood flooring throughout living and bedroom areas. Spacious open living room floorplan with custom shelving. *Kitchen with white subway tile backsplash, 42' cabinets, granite countertops. New 2016 stainless Whirlpool appliance package & upgraded kitchen faucet & hardware. Slate table/center island stays with unit. *Bedroom features shiplap barn-wood accent wall and large organized bedroom closet. Huge additional walk-in Elfa organized entry closet. *Bathroom features newer mirror, faucet, sink and built-in vintage cabinet. Front load 2018 GE in-unit washer and dryer. All interior doors refinished with custom molding and hardware. Plenty of room for work from home space and large balcony right off the living room. *This unit includes Garage parking space, located on the same floor steps from your unit. *Full amenity building featuring 24 hr. door staff, exercise room, community room, bike storage, additional unit storage locker and professionally managed. *Amazing location on quiet Desplaines AND close to Hospital Districts, lively West Loop restaurants and shopping. Walking distance to the Loop, Fulton Market District, 1 BEDROOM River North, Mariano's, Whole Foods, Target, Ogilvy Transportation Center, Union 1 BATH Station and the Blue Line.