Rhetorical Violence, Fundamentalist Eschatology, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

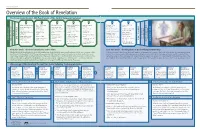

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Bible, Prophecy & Covid-19

BIBLE, PROPHECY & COVID-19 WHAT IS THE CHURCH AGE? • The Church age is the current period we are living in. It is also referred to as the age of grace RAPTURE ETERNITY MILLENIAL CHURCH AGE ETERNAL STATE PAST KINGDOM CREATION PENTECOST TRIBULATION WHAT IS THE RAPTURE? • When Believers will be instantaneously taken up to heaven. Rapture is the Latin translation of the New Testament Greek word harpazo found in 1Thess 4:13-18. RAPTURE ETERNITY MILLENIAL CHURCH AGE ETERNAL STATE PAST KINGDOM CREATION PENTECOST TRIBULATION WHAT IS THE TRIBULATION • The Tribulation is a future seven-year period when God’s wrath finally comes to judge evil in the world after a long period of grace. • This is distinct from the trials and tribulations that we all face in a fallen world. WHAT IS THE MILLENNIUM? • The millennium is a future 1,000 year period that begins after Christ’s return to Earth at the end of the tribulation. WHAT IS ETERNAL STATE? • This is the state of the final condition of the universe that results from the creation of a new heaven and a new earth with absolute perfection lasting for eternity. WHO IS THE ANTICHRIST? • The antichrist is a future world ruler who will rise to power during the tribulation • The false prophet is a world religious leaders who will unite the people of the earth and cause them to worship the antichrist. WHAT IS THE APOCALYPSE? • In scripture, it means the revealing or unveiling. • The Book of Revelation is the unveiling of God’s future plans WHAT IS ARMAGEDDON? • This refers to the hills of Megiddo. -

The Glory of God and Dispensationalism: Revisiting the Sine Qua Non of Dispensationalism

The Journal of Ministry & Theology 26 The Glory of God and Dispensationalism: Revisiting the Sine Qua Non of Dispensationalism Douglas Brown n 1965 Charles Ryrie published Dispensationalism Today. In this influential volume, Ryrie attempted to explain, I systematize, and defend the dispensational approach to the Scriptures. His most notable contribution was arguably the three sine qua non of dispensationalism. First, a dispensationalist consistently keeps Israel and the church distinct. Second, a dispensationalist consistently employs a literal system of hermeneutics (i.e., what Ryrie calls “normal” or “plain” interpretation). Third, a dispensationalist believes that the underlying purpose of the world is the glory of God.2 The acceptance of Ryrie’s sine qua non of dispensationalism has varied within dispensational circles. In general, traditional dispensationalists have accepted the sine qua non and used them as a starting point to explain the essence of dispensationalism.3 In contrast, progressive dispensationalists have largely rejected Ryrie’s proposal and have explored new ways to explain the essential tenants of Douglas Brown, Ph.D., is Academic Dean and Senior Professor of New Testament at Faith Baptist Theological Seminary in Ankeny, Iowa. Douglas can be reached at [email protected]. 2 C. C. Ryrie, Dispensationalism Today (Chicago: Moody, 1965), 43- 47. 3 See, for example, R. Showers, There Really Is a Difference, 12th ed. (Bellmawr, NJ: Friends of Israel Gospel Ministry, 2010), 52, 53; R. McCune, A Systematic Theology of Biblical Christianity, vol. 1 (Allen Park, MI: Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009), 112-15; C. Cone, ed., Dispensationalism Tomorrow and Beyond: A Theological Collection in Honor of Charles C. -

The City: the New Jerusalem

Chapter 1 The City: The New Jerusalem “I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem” (Revelation 21:2). These words from the final book of the Bible set out a vision of heaven that has captivated the Christian imagina- tion. To speak of heaven is to affirm that the human long- ing to see God will one day be fulfilled – that we shall finally be able to gaze upon the face of what Christianity affirms to be the most wondrous sight anyone can hope to behold. One of Israel’s greatest Psalms asks to be granted the privilege of being able to gaze upon “the beauty of the Lord” in the land of the living (Psalm 27:4) – to be able to catch a glimpse of the face of God in the midst of the ambiguities and sorrows of this life. We see God but dimly in this life; yet, as Paul argued in his first letter to the Corinthian Christians, we shall one day see God “face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12). To see God; to see heaven. From a Christian perspective, the horizons defined by the parameters of our human ex- istence merely limit what we can see; they do not define what there is to be seen. Imprisoned by its history and mortality, humanity has had to content itself with pressing its boundaries to their absolute limits, longing to know what lies beyond them. Can we break through the limits of time and space, and glimpse another realm – another dimension, hidden from us at present, yet which one day we shall encounter, and even enter? Images and the Christian Faith It has often been observed that humanity has the capacity to think. -

Premillennialism in the New Testament: Five Biblically Doctrinal Truths

MSJ 29/2 (Fall 2018) 177–205 PREMILLENNIALISM IN THE NEW TESTAMENT: FIVE BIBLICALLY DOCTRINAL TRUTHS Gregory H. Harris Professor of Bible Exposition The Master’s Seminary Many scholars hold that premillennial statements are found only in Revelation 20:1–10. Although these verses are extremely important in supporting the premillen- nial doctrine, many other verses throughout the New Testament also offer support for premillennialism. Our study limits itself to five biblically doctrinal premillennial truths from the New Testament that seamlessly blend throughout the Bible with the person and work—and reign—of Jesus the Messiah on earth after His Second Com- ing. * * * * * Introduction Whenever discussions between premillennialists and amillennialists occur, Revelation 19 and 20 is usually the section of Scripture on which many base their argumentation, especially Revelation 20:1–10. Before we examine these specific pas- sages, we know that God has already made several prophecies elsewhere. And how one interprets these passages has been determined long before by how those other related futuristic biblical texts have already been interpreted, before ever approaching certain crucial biblical passages such as Revelation 20:1–10. So, as we shall see, one should actually end the argumentation for this important component of eschatological theology in Revelation 19–20, not start there. In setting forth the New Testament case for premillennialism we will present the following: (1) a presentation of three of the five premillennial biblical truths -

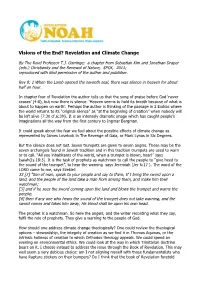

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change By The Revd Professor T.J. Gorringe; a chapter from Sebastian Kim and Jonathan Draper (eds.) Christianity and the Renewal of Nature, SPCK, 2011; reproduced with kind permission of the author and publisher. Rev 8: 1 When the Lamb opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven for about half an hour. In chapter four of Revelation the author tells us that the song of praise before God ‘never ceases’ (4:8), but now there is silence. ‘Heaven seems to hold its breath because of what is about to happen on earth’. Perhaps the author is thinking of the passage in 2 Esdras where the world returns to its “original silence” as “at the beginning of creation” when nobody will be left alive (7:30 cf.6:39)i. It is an intensely dramatic image which has caught people’s imaginations all the way from the first century to Ingmar Bergman. It could speak about the fear we feel about the possible effects of climate change as represented by James Lovelock in The Revenge of Gaia, or Mark Lynas in Six Degrees. But the silence does not last. Seven trumpets are given to seven angels. These may be the seven archangels found in Jewish tradition and in this tradition trumpets are used to warn or to call. “All you inhabitants of the world, when a trumpet is blown, hear!” says Isaiah(Is.18:3) It is the task of prophets as watchmen to call the people to “give heed to the sound of the trumpet”, to hear the warning says Jeremiah (Jer 6:17 ). -

Sermon Notes

Screen 1 Screen 2 “The Seven Bowls” Revelation 16:1-21 June 13, 2021 In this chapter of the Revelation, we now come to the final series of numbered plagues. Somebody say, “Amen!” Once again, we encounter the four and three structure in which the first four plagues are closely related, and the final three intensify the entire series. Now thus far we have discussed the seven seals in Revelation 6 thru 8:5; the seven trumpets in Revelation 8:6 thru 11:19. Now we have the seven bowls of God’s wrath. It parallels between this series of judgments and the trumpet plagues are readily apparent. In each series the first four plagues are visited upon the earth (see Island Waters and Heavenly Bodies respectively). The fifth involves darkness and pain (Revelation 16:10; 9:2, 5-6). The sixth involves enemy hordes from the vicinity of Euphrates (cross referenced Chapter 16:12 with Revelation 9:14 ff). Both series draw heavily from the symbolism of the ten Egyptian plagues: 1. The turning of water into blood – Revelation 8:8; 16:3-4 parallels the first Egyptian plague where Moses struck the water of the Nile turning it into blood in Exodus 7:20. 2. The darkening of the sun – Revelation 8:12 (cross reference with 16:10). Its counterpart is in the ninth Egyptian plague in which darkness prevailed over the land for three days in Exodus 10:21-22. In this sermon we will discuss other parallels as well. Now while it is true that while both the seven trumpet plagues and the seven bowl plagues deal with the same crucial period of time just before the end, there are some significant differences in the two series: 1 1. -

Introduction to the Millennial Kingdom

What Must Take Place After This (The Millennial Kingdom & the Great White Throne) Text: Revelation 20 Main Idea: When Christ returns He will defeat His enemies, have Satan bound, and set up His throne in Jerusalem and reign for a thousand years on the earth. At the end of the millennial reign Christ will defeat Satan, who will be released, and an army of unbelievers. At that point the whole earth will be destroyed, and all the unsaved through the ages will be resurrected and given bodies to stand before the Great White Throne Judgment and will be cast into eternal hell to be tormented forever and ever. Introduction to the Millennial Kingdom The Three Major Positions: • Amillennialism: The “a” means without. This is misleading because those who hold this position do not reject the concept of an earthly millennium, a kingdom. They believe Old Testament prophecies of the Messiah’s kingdom, but believe that those prophesies are being fulfilled ______currently__________, either by the saints reigning in heaven with Christ, or by the church on the earth. Amillennialists believe that the millennial kingdom is happening right now spiritually. But they do deny a literal reign of Christ on the earth. The hermeneutic of the Amillennialist forces them to interpret everything spiritual. • Postmillennialism: “Postmillennialism is in some ways the opposite of premillennialism. Premillennialism teaches that Christ will return before the Millennium; postmillennialism teaches that He will return at the end of the Millennium. Premillennialism teaches that the period immediately before Christ’s return will be the worst in human history; postmillennialism teaches that before His return will come the best period in history, so that Christ will return at the end of a long golden age of peace and harmony….That golden age, according to postmillennialism, will result from the spread of the ______Gospel___________ throughout the world and the conversion of a majority of the human race to Christianity. -

SEALS, TRUMPETS and BOWLS

SEALS, TRUMPETS and BOWLS The seven seals (Revelation 6:1-17 , 8:1-5), seven trumpets (Revelation 8:6-9:21 ; 11:15-19 ), and seven bowls/vials (Revelation 16:1-21 ) are three succeeding series of end-times judgments from God. The judgments get progressively worse and more devastating as the end times progress. The seven seals, trumpets, and bowls are connected to one another. The seventh seal introduces the seven trumpets (Revelation 8:1-5), and the seventh trumpet introduces the seven bowls (Revelation 11:15-19 , 15:1-8). The first four of the seven seals are known as the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. The first seal introduces the Antichrist (Revelation 6:1-2). The second seal causes great warfare (Revelation 6:3-4). The third of the seven seals causes famine (Revelation 6:5-6). The fourth seal brings about plague, further famine, and further warfare (Revelation 6:7-8). The fifth seal tells us of those who will be martyred for their faith in Christ during the end times (Revelation 6:9-11 ). God hears their cries for justice and will deliver it in His timing—in the form of the sixth seal, along with the trumpet and bowl judgments. When the sixth of the seven seals is broken, a devastating earthquake occurs, causing massive upheaval and terrible devastation—along with unusual astronomical phenomena (Revelation 6:12-14 ). Those who survive are right to cry out, “Fall on us and hide us from the face of him who sits on the throne and from the wrath of the Lamb! For the great day of their wrath has come, and who can stand?” (Revelation 6:16-17 ). -

The Recurrent Usage of Daniel in Apocalyptic Movements in History Zachary Kermitz

Florida State University Libraries Honors Theses The Division of Undergraduate Studies 2012 The Recurrent Usage of Daniel in Apocalyptic Movements in History Zachary Kermitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Abstract: (Daniel, apocalypticism, William Miller) This thesis is a comparison of how three different apocalyptic religious groups interpret the Book of Daniel as referring to their particular group and circumstances despite the vast differences from the book’s original context. First, the authorship of the book of Daniel itself is analyzed to establish the original intent of the book and what it meant to its target audience in the second century BCE. This first chapter is also used as a point of comparison to the other groups. Secondly, the influence of Daniel on the authorship of the book of Revelation and early Christianity is examined. In the third chapter, the use of Daniel amongst the Millerites, a nineteenth century American apocalyptic religious movement is analyzed. To conclude, the use of Daniel amongst the three groups is compared allowing for conclusions of how these particular groups managed to understand the book of Daniel as referring to their own particular group and circumstances with some attention paid to modern trends in interpretation as well. THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RECURRENT USAGE OF DANIEL IN APOCALYPTIC MOVEMENTS IN HISTORY By ZACHARY KERMITZ A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Spring, 2012 2 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Zachary Kermitz defended on April 13, 2012. -

Demystifying the Number of the Beast in the Book of Revelation: Examples of Ancient Cryptology and the Interpretation of the “666” Conundrum

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 2010 Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum M G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M G.: Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/3585 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum Abstract As the year 2000 came and went, with the suitably forecasted fuse-box of utopian and apocalyptic responses, the question of "666" (Rev 13:18) was once more brought to our attention in different ways. Biblical scholars, for instance, focused again on the interpretation of the notorious conundrum and on the Traditionsgeschichte of Antichrist. For some of those commentators it was a reply to the outpouring of sensationalist publications fuelled by the millennial mania. This paper aims to shed some light on the background, the sources, and the interpretation of the “number of the beast”. It explores the ancient techniques for understanding the conundrum including: gematria, arithmetic, symbolic, and riddle-based solutions. -

The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15 Rebekah Yi Liu [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Rebekah Yi, "The Background and Meaning of the Image of the Beast in Rev. 13:14, 15" (2016). Dissertations. 1602. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1602 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE BACKGROUNDS AND MEANING OF THE IMAGE OF THE BEAST IN REV 13:14, 15 by Rebekah Yi Liu Adviser: Dr. Jon Paulien ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STDUENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE BACKGROUNDS AND MEANING OF THE IMAGE OF THE BEAST IN REV 13:14, 15 Name of researcher: Rebekah Yi Liu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jon Paulien, Ph.D. Date Completed: May 2016 Problem This dissertation investigates the first century Greco-Roman cultural backgrounds and the literary context of the motif of the image of the beast in Rev 13:14, 15, in order to answer the problem of the author’s intended meaning of the image of the beast to his first century Greco-Roman readers. Method There are six steps necessary to accomplish the task of this dissertation.