Love Eterne in Contemporary Queer Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

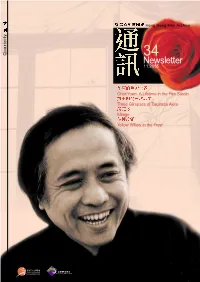

Newsletter 34

Hong Kong Film Archive Quarterly 34 Newsletter 11.2005 Chor Yuen: A Lifetime in the Film Studio Three Glimpses of Takarada Akira Mirage Yellow Willow in the Frost 17 Editorial@ChatRoom English edition of Monographs of HK Film Veterans (3): Chor Yuen is to be released in April 2006. www.filmarchive.gov.hk Hong Kong Film Archive Head Angela Tong Section Heads Venue Mgt Rebecca Lam Takarada Akira danced his way in October. In November, Anna May Wong and Jean Cocteau make their entrance. IT Systems Lawrence Hui And comes January, films ranging from Cheung Wood-yau to Stephen Chow will be revisited in a retrospective on Acquisition Mable Ho Chor Yuen. Conservation Edward Tse Reviewing Chor Yuen’s films in recent months, certain scenes struck me as being uncannily familiar. I realised I Resource Centre Chau Yu-ching must have seen the film as a child though I couldn’t have known then that the director was Chor Yuen. But Research Wong Ain-ling coming to think of it, he did leave his mark on silver screen and TV alike for half a century. Tracing his work brings Editorial Kwok Ching-ling Programming Sam Ho to light how Cantonese and Mandarin cinema evolved into Hong Kong cinema. Today, in the light of the Chinese Winnie Fu film market and the need for Hong Kong cinema to reorient itself, his story about flowers sprouting from the borrowed seeds of Cantonese opera takes on special meaning. Newsletter I saw Anna May Wong for the first time during the test screening. The young artist was heart-rendering. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Annual Report 2002-2003 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability)

2002-2003 Annual Report (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) 年報 2002-2003 年報 Annual Report 2002-2003 Panorama International Holdings Limited PanoramaAnnual Report 2002-2003 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GROWTH ENTERPRISE MARKET (“GEM”) OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED (THE “STOCK EXCHANGE”). GEM has been established as a market designed to accommodate companies to which a high investment risk may be attached. In particular, companies may list on GEM with neither a track record of profitability nor any obligation to forecast future profitability. Furthermore, there may be risks arising out of the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM and the business sectors or countries in which the companies operate. Prospective investors should be aware of the potential risks of investing in such companies and should make the decision to invest only after due and careful consideration. The greater risk profile and other characteristics of GEM mean that it is a market more suited to professional and other sophisticated investors. Given the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM, there is a risk that securities traded on GEM may be more susceptible to high market volatility than securities traded on the Main Board of the Stock Exchange and no assurance is given that there will be a liquid market in the securities traded on GEM. The principal means of information dissemination on GEM is publication on the Internet website operated by the Stock Exchange. Listed companies are not generally required to issue paid announcements in gazetted newspapers. Accordingly, prospective investors should note that they need to have access to the GEM website in order to obtain up-to-date information on GEM- listed issuers. -

The Pop Scene Around the World Andrew Clawson Iowa State University

Volume 2 Article 13 12-2011 The pop scene around the world Andrew Clawson Iowa State University Emily Kudobe Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival Recommended Citation Clawson, Andrew and Kudobe, Emily (2011) "The pop cs ene around the world," Revival Magazine: Vol. 2 , Article 13. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival/vol2/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revival Magazine by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clawson and Kudobe: The pop scene around the world The POP SCENE Around the World Taiwan Hong Kong Japan After the People’s Republic of China was Japan is the second largest music market Hong Kong can be thought of as the Hol- established, much of the music industry in the world. Japanese pop, or J-pop, is lywood of the Far East, with its enormous left for Taiwan. Language restrictions at popular throughout Asia, with artists such film and music industry. Some of Asia’s the time, put in place by the KMT, forbade as Utada Hikaru reaching popularity in most famous actors and actresses come the use of Japanese language and the the United States. Heavy metal is also very from Hong Kong, and many of those ac- native Hokkien and required the use of popular in Japan. Japanese rock bands, tors and actresses are also pop singers. -

Media Asia Group Holdings Limited (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands and Continued in Bermuda with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 8075)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Media Asia Group Holdings Limited (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands and continued in Bermuda with limited liability) (Stock Code: 8075) ANNOUNCEMENT OF THIRD QUARTERLY RESULTS FOR THE NINE MONTHS ENDED 30 APRIL 2018 CHARACTERISTICS OF GEM OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED (THE “STOCK EXCHANGE”) GEM has been positioned as a market designed to accommodate small and mid-sized companies to which a higher investment risk may be attached than other companies listed on the Stock Exchange. Prospective investors should be aware of the potential risks of investing in such companies and should make the decision to invest only after due and careful consideration. Given that the companies listed on GEM are generally small and mid-sized companies, there is a risk that securities traded on GEM may be more susceptible to high market volatility than securities traded on the Main Board of the Stock Exchange and no assurance is given that there will be a liquid market in the securities traded on GEM. This announcement, for which the directors of Media Asia Group Holdings Limited (the “Directors”) collectively and individually accept full responsibility, includes particulars given in compliance with the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on GEM (the “GEM Listing Rules”) for the purpose of giving information with regard to Media Asia Group Holdings Limited. -

Introduction

introduction The disembodied voices of bygone songstresses course through the soundscapes of many recent Chinese films that evoke the cultural past. In a mode of retro- spection, these films pay tribute to a figure who, although rarely encountered today, once loomed large in the visual and acoustic spaces of popu lar music and cinema. The audience is invited to remember the familiar voices and tunes that circulated in these erstwhile spaces. For instance, in a film by the Hong Kong director Wong Kar- wai set in the 1960s, In the Mood for Love, a traveling businessman dedicates a song on the radio to his wife on her birthday.1 Along with the wife we listen to “Hua yang de nianhua” (“The Blooming Years”), crooned by Zhou Xuan, one of China’s most beloved singers of pop music. The song was originally featured in a Hong Kong production of 1947, All- Consuming Love, which cast Zhou in the role of a self- sacrificing songstress.2 Set in Shang- hai during the years of the Japa nese occupation, the story of All- Consuming Love centers on the plight of Zhou’s character, who is forced to obtain a job as a nightclub singer to support herself and her enfeebled mother-in- law after her husband leaves home to join the resis tance. “The Blooming Years” refers to these recent politi cal events in a tone of wistful regret, expressing the home- sickness of the exile who yearns for the best years of her life: “Suddenly this orphan island is overshadowed by miseries and sorrows, miseries and sorrows; ah, my lovely country, when can I run into your arms again?”3 -

Research on Audience Engagement in Film Marketing

Department of Informatics and Media Master’s Program in Social Sciences, Digital Media and Society Specialization Two-year Master’s Thesis Research on Audience Engagement in Film Marketing -- Taking the film <Us and Them> as the Case Student: Ruiyan Huang Supervisor: Cecilia Strand Spring 2019 Abstract The film marketing is becoming increasingly important due to the fierce competition of film industry in China. With the drive of technology innovations, the creation of interaction among audiences has gradually become the spotlight of film marketing and many social media platforms are employed as marketing tools to encourage or foster audience engagement. Through the case study of Us and Them, the thesis studies how audience engagement is realized through film marketing strategies made by marketers, so as to identify the specific marketing strategies or techniques used for enhancing the audience engagement and promoting the film. As different marketing techniques will lead to different level of audience engagement, that are normally reflected by the preferences of audiences, their behaviors on social media and the way of involving into film contents, it is necessary to explore and understand the effectiveness and efficiency of these techniques, so that the film marketing can be improved while practical marketing progressing. Keywords Audience engagement, film marketing, social media, marketing content 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank Swedish Institute, offering me the platform so I could have chance to get the master’s degree in Uppsala University in Sweden. Most importantly, I would like to thank Cecilia Strand, my thesis supervisor, who guided me and gave me suggestions to finish the thesis. -

Tiff Bell Lightbox Celebrates a Century of Chinese Cinema with Unprecedented Film Series, Exhibitions and Special Guests

May 6, 2013 .NEWS RELEASE. TIFF BELL LIGHTBOX CELEBRATES A CENTURY OF CHINESE CINEMA WITH UNPRECEDENTED FILM SERIES, EXHIBITIONS AND SPECIAL GUESTS - Programme features 80 films, free exhibitions and guests including Chen Kaige, Johnnie To and Jackie Chan - -Tickets on sale May 21 at 10 a.m. for TIFF Members, May 27 at 10 a.m. for non-members - Toronto – Noah Cowan, Artistic Director, TIFF Bell Lightbox, announced today details for a comprehensive exploration of Chinese film, art and culture. A Century of Chinese Cinema features a major film retrospective of over 80 titles, sessions with some of the biggest names in Chinese cinema, and a free exhibition featuring two internationally acclaimed visual artists. The flagship programme of the summer season, A Century of Chinese Cinema runs from June 5 to August 11, 2013. “A Century of Chinese Cinema exemplifies TIFF’s vision to foster new relationships and build bridges of cultural exchange,” said Piers Handling, Director and CEO of TIFF. “If we are, indeed, living in the Chinese Century, it is essential that we attempt to understand what that entails. There is no better way to do so than through film, which encourages cross-cultural understanding in our city and beyond.” “The history, legacy and trajectory of Chinese film has been underrepresented in the global cinematic story, and as a leader in creative and cultural discovery through film, TIFF Bell Lightbox is the perfect setting for A Century of Chinese Cinema,” said Noah Cowan, Artistic Director, TIFF Bell Lightbox. “With Chinese cinema in the international spotlight, an examination of the history and development of the region’s amazing artistic output is long overdue. -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’S Introduction

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’s Introduction [accepted for publication in The Opera Quarterly, Oxford University Press] © Cormac Newark 2018 What has the Phantom got to do with opera? Music(al) theater sectarians of all denominations might dismiss the very question, but for the opera studies community, at least, it is possible to imagine interesting potential answers. Some are historical, some technical, and some to do with medium and genre. Others are economic, invoking different commercial models and even (in Europe at least) complex arguments surrounding public subsidy. Still others raise, in their turn, further questions about the historical and contemporary identities of theatrical institutions and the productions they mount, even the extent to which particular works and productions may become institutions themselves. All, I suggest, are in one way or another related to opera reception at a particular time in the late nineteenth century: of one work in particular, Gounod’s Faust, but even more to the development of a set of popular ideas about opera and opera-going. Gaston Leroux’s serialized novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, set in and around the Palais Garnier, apparently in 1881, certainly explores those ideas in a uniquely productive way.1 As many (but perhaps not all) readers will recall, it tells the story of the debut in a principal role of Christine Daaé, a young Swedish soprano who is promoted when the Spanish prima donna, Carlotta, is indisposed.2 In the course of a gala performance in honor of the outgoing Directors of the Opéra, she is a great success in extracts of works 1 The novel was serialized in Le Gaulois (23 September 1909–8 January 1910) and then published in volume-form: Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (Paris: Lafitte, 1910). -

NYCAS 2012 Abstractdownload

NYCAS 2012, PANEL SESSION A, Sep. 28 (Fri), 12:30-2:15 PM A1 Popular Religious Art in South Asia: The Pilgrim Trade SUB 62 Chair: Richard Davis (Bard College) Discussant: Kristin Scheible (Bard College) North Indian Pilgrimage and Portable Imagery Kurt Behrendt (Metropolitan Museum of Art) The north Indian pilgrimage sites associated with the Buddha were important for both local communities and devotees coming from distant countries. This paper focuses on 7th- 12th century imagery that was acquired at these centers and which circulated within the greater Buddhist world. Most popular were inexpensive molded clay plaques, but small stone and bronze images also moved with these pious devotees. By the end of this period small secret esoteric images were being used by a select group of monks within the great north Indian monasteries. This paper will conclude by suggesting that such private images also circulated with pilgrims, given their scale and significance as objects of power, and that they had a major impact on Buddhist communities outside of India. A Jagannatha Triad in the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art Jaclynne Kerner (SUNY New Paltz) This paper will explore Hindu devotional practice in relation to a painted Jagannatha Triad [Jagannatha, Subhadra, and Balabhadra Enshrined] in the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz. Perhaps as early as the eighth century, the Orissan town of Puri was the birthplace of a distinctive pata painting tradition associated with the worship of Jagannatha, an abstract form of Krishna. My discussion will focus primarily on the development and continuity of Jagannatha iconography and the idiosyncratic Orissan pata style. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-007>

| FRIDAY, JUNE 29, 2018 | THE STRAITS TIMES | happenings life D7 FILMS Jimami Tofu (2017) Yip Wai Yee Entertainment Correspondent recommends Created by Singapore’s BananaMana Films, the award-winning film will be featured in a free public screening at the Botanic Gardens tomorrow night. Picks PHOTOS: Audiences stand to win return Jetstar ASSOCIATED tickets to Okinawa in a lucky draw at PRESS, NETFLIX, the end of the movie. Okinawan picnic Film THE PROJECTOR baskets featuring the Ryukyu dynastic food portrayed in the film can be purchased online at bit.ly/BuyPicnic. WHERE: Eco Lake Movie Lawn, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road MRT: Botanic Gardens WHEN: Tomorrow, 7pm ADMISSION: Free INFO: https://bit.ly/2N3yfoa Tomboy (2011, NC16) A French family with two sisters, 10-year-old Laure and six-year-old Jeanne, moves to a new neighbourhood during the summer holidays. With her Jean Seberg pixie haircut and tomboy ways, Laure is immediately mistaken for a boy by the local kids and passes herself off as Michael. In French, with English subtitles. WHERE: Green Room, The Projector, Level 5 Golden Mile Tower, 6001 Beach Road MRT: Nicoll Highway WHEN: July 7 & 15, 5.30pm; July 21, 2.30pm ADMISSION: $13.50 (standard), $11.50 (concession) INFO: theprojector.sg God’s Own Country (2017) Isolated young sheep farmer Johnny Saxby numbs his daily frustrations with binge drinking and casual sex, until the arrival of a Romanian migrant worker Gheorghe, employed US AND THEM (PG13) for the lambing season, ignites an 118 mins/Now showing on Netflix CARGO (M18) intense relationship that sets Saxby 105 mins/Now showing on Netflix on a new path.