The Automobile Exception: What It Is and What It Is Not -- a Rationale in Search of a Clearer Label

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August of 2019 Newsletter

Traveling with the Payson Arizona AUGUST 2019 PRESIDENT Steve Fowler THE RIM COUNTRY CLASSIC AUTO CLUB IS A NON-PROFIT If you read your e-mails, you know that Richard Graves ORGANIZATION FOR stepped down as President, so this monthly missive THE PURPOSE OF: falls to me. I’d like to express my gratitude to the Providing social, educational members of the board and others who became aware and recreational activities of the changes for their unwavering support. We for its membership. anticipate a smooth transition. Also, many thanks to Participating in and support- those who have come forward this year and ing civic activities for the betterment of the community. volunteered to spearhead activities for a particular Encouraging and promoting month. This has thus far worked out quite well and the preservation and restora- helped spread the load out to more members. I think tion of classic motor vehicles. that those who have done so would agree that it is not Providing organized activities involving the driving and a particularly difficult task, just takes a little effort to showing of member’s cars. put ideas into motion. This also holds true on the efforts involved in putting on our annual car show. The old saying that “many hands make light work” is very RCCAC meets at true, and we actually have fun doing it! 6:30p.m. on the first It was with much sadness and surprise that we learned Wednesday of the month at of the passing of Ron Trainor this past month. I’d had Tiny’s Restaurant, 600 the opportunity to work with him on his Impala and to E. -

Award Winners

Presented by The Rotary Club of Forest Grove Sunday July 17, 2016 Award Winners Best in Show Sponsored by: BMW Portland 1937 Cord Super Charged 812 Norman and Judi Noakes, Lake Oswego, Oregon Best Classic Car Sponsored by: Barrett-Jackson Auction Company 1937 Cord Super Charged 812 Norman and Judi Noakes, Lake Oswego, Oregon Best Open Car Sponsored by: Knights of Pythais 1958 Porsche 356A Cabriolet Ernie Spada, Lake Oswego, Oregon Best Closed Car Sponsored by: Rotary Club of Forest Grove 1947 Chrysler Town & Country Alan and Sandi McEwan Redmond, Washington Pacific University President's Award Sponsored by: Columbia Bank 1971 BMW 3.0 CSL Alpina B2S Peter and Jennifer Gleeson, Edmunds, Washington Guy and Flo Carr Award Sponsored by: Carr Chevrolet Subaru 1954 Chevrolet Corvette Steve Chaney, Vancouver, Washington Best Rod Award Sponsored by: Rotary Club of Forest Grove 1934 Ford Roadster Randy Downs, Portland, Oregon Allen C. Stephens Elegance Award Sponsored by: The Stephens Family 1964 Jaguar XKE Clifford Mays, Vancouver, Washington Best Custom Award Sponsored by: Rotary Club of Forest Grove 1958 Chevrolet Impala Ray Hamness Portland, Oregon Rotary President's Award Sponsored by: Rotary Club of Forest Grove 1967 Lincoln Continental Ron Wade Vancouver, Washington Larry Douroux Memorial Award Sponsored by: Howard Freedman - Packards of Oregon 1940 Packard 180 Bill Jabs Eagle Creek, Oregon People's Choice Sponsored by: Sports Car Market Magazine 1931 Lincoln K205 Larry Knowles Tulalip, Washington Spirit of Motoring Sponsored by: Sports Car Market Magazine 1962 Volkswagen Beetle Timothy Walbridge and Cera Ruesser, Beaverton, Oregon Jerry Hanauska Memorial Award Sponsored by: Howard Freedman - Classic Car Club of America - Oregon Region 1923 Lincoln Roadster 111 Mike and Diane Barrett, Nooksack, Washington Dr. -

Annual Report 2019

Contents Corporate Profile 2 Corporate Information 4 Our Products 6 Business Overview 13 Financial Highlights 32 CEO’s Statement 33 Management Discussion and Analysis 36 Directors and Senior Management 48 Directors’ Report 56 Corporate Governance Report 74 Independent Auditor’s Report 86 Consolidated Balance Sheet 92 Consolidated Income Statement 94 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 95 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 96 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 97 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 98 Five Years’ Financial Summary 168 02 NEXTEER AUTOMOTIVE GROUP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Corporate Profile Nexteer Automotive Group Limited (the Company) together with its subsidiaries are collectively referred to as we, us, our, Nexteer, Nexteer Automotive or the Group. Nexteer Automotive is a global leader in advanced steering and driveline systems, as well as advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and automated driving (AD) enabling technologies. In-house development and full integration of hardware, software and electronics give Nexteer a competitive advantage as a full-service supplier. As a leader in intuitive motion control, our continued focus and drive is to leverage our design, development and manufacturing strengths in advanced steering and driveline systems that provide differentiated and value-added solutions to our customers. We develop solutions that enable a new era of safety and performance for traditional and varying levels of ADAS/AD. Overall, we are making driving safer, more fuel-efficient and fun for today’s world and an automated future. Our ability to seamlessly integrate our systems into automotive original equipment manufacturers’ (OEM) vehicles is a testament to our more than 110-year heritage of vehicle integration expertise and product craftsmanship. -

The Ohio Motor Vehicle Industry

Research Office A State Affiliate of the U.S. Census Bureau The Ohio Motor Vehicle Report February 2019 Intentionally blank THE OHIO MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY FEBRUARY 2019 B1002: Don Larrick, Principal Analyst Office of Research, Ohio Development Services Agency PO Box 1001, Columbus, Oh. 43216-1001 Production Support: Steven Kelley, Editor; Jim Kell, Contributor Robert Schmidley, GIS Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 1 Description of Ohio’s Motor Vehicle Industry 4 The Motor Vehicle Industry’s Impact on Ohio’s Economy 5 Ohio’s Strategic Position in Motor Vehicle Assembly 7 Notable Motor Vehicle Industry Manufacturers in Ohio 10 Recent Expansion and Attraction Announcements 16 The Concentration of the Industry in Ohio: Gross Domestic Product and Value-Added 18 Company Summaries of Light Vehicle Production in Ohio 20 Parts Suppliers 24 The Composition of Ohio’s Motor Vehicle Industry – Employment at the Plants 28 Industry Wages 30 The Distribution of Industry Establishments Across Ohio 32 The Distribution of Industry Employment Across Ohio 34 Foreign Investment in Ohio 35 Trends 40 Employment 42 i Gross Domestic Product 44 Value-Added by Ohio’s Motor Vehicle Industry 46 Light Vehicle Production in Ohio and the U.S. 48 Capital Expenditures for Ohio’s Motor Vehicle Industry 50 Establishments 52 Output, Employment and Productivity 54 U.S. Industry Analysis and Outlook 56 Market Share Trends 58 Trade Balances 62 Industry Operations and Recent Trends 65 Technologies for Production Processes and Vehicles 69 The Transportation Research Center 75 The Near- and Longer-Term Outlooks 78 About the Bodies-and-Trailers Group 82 Assembler Profiles 84 Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV 86 Ford Motor Co. -

'Vetter's Letter

Allentown Area Corvette Club, Inc. ‘Vetter’s Letter November 2013 Volume 20, Issue 11 President Jeff Mohring From the val Office 610-392-6898 [email protected] Hello Corvette Enthusiasts, Vice-President Laura Hegyi I can’t believe that another month has come and gone already. 610-730-2695 As most of you know I am out‐of‐town on a work assignment and not able to attend our monthly meetings for a few months. With that being said, Secretary Carol Jenkins I am still very “connected” to my Corvette Family. Thanks to the wonderful world 610-317-9277 of technology — email, cell phones, and computers — staying connected has Treasurer never been easier. Janet Mohring 610-965-8593 Hopefully by now most of you have seen the all‐new C7 Stingray up close and personal. I had the good fortune of having a ride in one and was impressed NCCC Governor Joel Dean beyond words. The entire Corvette team at Chevrolet should be very proud of 610-533-2259 their achievement. It is a remarkable and impressive sports car, especially when Membership you look at the price point. Looking over dealers’ websites, it appears the C7 Marty & Laura Hegyi availability is becoming less restricted. 610-730-2695 [email protected] In closing, I would like to say Thank You to our club’s Vice President, Laura Hegyi, Events for filling in for me during my absence. I look forward to seeing everyone again at John Kostick, Jr. our December meeting and at our Holiday Party at the Barn House. 610-432-7172 Be safe, Be well, NCM Ambassador Rich Ringhoffer 610-867-6494 Jeff Mohring AACC President Newsletter Editors Kevin & Michelle Minnich 610-530-0923 [email protected] Webmaster AACC Meetings @ Blue Monkey Bud Benton 610-252-0989 The Allentown Area Corvette Club meets at 8:00 p.m. -

Summer-Fall 2014 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol

Summer-Fall 2014 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol. 28 Number 2 IN THIS ISSUE: • RECENT ACQUISITIONS • UPCOMING EXHIBITS • STUDENT PHOTOGRAPHY AT FONTHILL • ANNUAL FUND 2013 • ADOPT-AN-ARTIFACT • SAVE THE DATE: COCKTAILS AT THE CASTLE • AND MORE! Members’ Reception Members came out to enjoy the opening of the Mercer Museum’s newest exhibit, America’s Road: The Journey of Route 66. Guests chowed down on “road food” including sliders, milkshakes and fries. Tom Schwabe (right) remembers his cousin, Route 66 songwriter, Bobby Troup. With Cory Amsler, Mercer Museum Vice President of Collections & Interpretation. Exhibit sponsor, Glenmede, in the Great Hall. From left to right: Matt Cross, Karl Murray, Mike Schiff, Jim Harris and Joe Stole. Exhibit sponsor, Fred Beans Family of Dearlerships. From left to right: Barbara Beans, Beth Beans Gilbert and Fred Beans. Tom Thomas and Yvonne Marlier admire the Oldsmobile “woodie.” Front Cover: Photo of the Mercer Museum’s Central Court by Young guests enjoy the “road” food. amateur photographer, Brian Kutner. Brian uses the process of tone mapping to enhance the detail in a digital image. 2 And the Mercer Legacy Sweepstakes Making All That We Winner is... Do Possible ore than 300 guests gathered at Fonthill Castle on April 27th to enjoy a MCinco de Mayo themed party and await the announcement of the 2014 Mercer Legacy Sweepstakes grand prize winner. Robert Graham was the grand prize winner, selecting the $20,000. “It was an unbelievable feeling when I heard my name and I had to double check to make sure I won,” said Robert. -

Amping up Electric Vehicle Manufacturing in the PNW OPPORTUNITIES for BUSINESS, WORKFORCE, and EDUCATION

Amping Up Electric Vehicle Manufacturing in the PNW OPPORTUNITIES FOR BUSINESS, WORKFORCE, AND EDUCATION Seattle Jobs Initiative 1200 12TH AVENUE SOUTH | SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 1 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Tables ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Figures .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 5 The Openings for New Business that Electric Vehicle Production Can Create ............................................ 8 Good News: The Barriers to Entry Are Lower in EV-Related Industries ................................................... 9 Who Could Enter the EV Field? The Supply Chain in More Detail ......................................................... 10 Existing and Potential Businesses in the EV-Related Industries ................................................................ 13 Identifying EV-Related Firms in Oregon and Washington ...................................................................... -

Toolkit for Advanced Transportation Policies Improving Environmental, Economic, and Social Outcomes for States and Local Governments Through Transportation

g1CA Toolkit for Advanced Transportation Policies Improving Environmental, Economic, and Social Outcomes for States and Local Governments Through Transportation October 2018 Acknowledgments Lead Authors: Carrie Jenks, Grace Van Horn, Lauren Slawsky, Sophia Hill, M.J. Bradley & Associates, LLC In addition, the authors thank the following for their helpful contributions to and input on the report: Albert Benedict, Shared-Use Mobility Center; James Bradbury, Georgetown Climate Center; Tom Cackette, Tom Cackette Consulting; JoAnn Covington, Proterra; David Hayes, State Energy & Environmental Impact Center; Miles Keogh, National Association of Clean Air Agencies (NACAA); Kathy Kinsey, Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM); Will Toor, Southwest Energy Efficiency Project; and Alyssa Y. Tsuchiya, Union of Concerned Scientists. This report reflects the analysis and judgment of the authors only and does not necessarily reflect the views of any of the reviewers. The authors would also like to thank Gary S. Guzy and Thomas Brugato, Covington and Burling LLC, for the legal analysis contained within this report as well as the Environmental Defense Fund for the support to develop this report. This report is available at www.mjbradley.com. About M.J. Bradley & Associates M.J. Bradley & Associates, LLC (MJB&A), founded in 1994, is a strategic consulting firm focused on energy and environmental issues. The firm includes a multi-disciplinary team of experts with backgrounds in economics, law, engineering, and policy. The company works with private companies, public agencies, and non-profit organizations to understand and evaluate environmental regulations and policy, facilitate multi-stakeholder initiatives, shape business strategies, and deploy clean energy technologies. © M.J. -

THE PUGET SOUND ROCKET Newsletter of the Puget Sound Olds Club an Official Chapter of the Oldsmobile Club of America

THE PUGET SOUND ROCKET Newsletter of the Puget Sound Olds Club An Official Chapter of the Oldsmobile Club of America OCTOBER 2017 Above is the show field at the Annual BOP Show at the XXX Root Beer Drive-In on Sept. 3. The 2017 BOP Show was blessed with good weather. There was no rain this year! We did have some smoke from the wild fires in the mountains that dropped ash on our cars late in the day. The run of 80 degree plus days continued for our show. 57 registered cars and eight un-registered cars were on the show field. Oldsmobiles dominated the show with 24 cars in attendance. The Buick chapters brought 17 cars and the Pontiac clubs had 16 registered cars on the field. The date for the 2018 BOP Show has been selected and as this year, it will the Sunday of Labor Day Weekend. If you missed the show this year (and we know who you are), you now have time to put the date on your calendar, fix whatever is not working on your car, and join us for another great show. If you will need a wake-up call, send us an e-mail and we will have the front desk call you. Between the Bumpers MEETING MINUTES CLASSIFIEDS Page 3 No September Meeting Page 11 Page 15 1 Puget Sound Olds Club President’s Message 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS PSOC Members, President Ed Konsmo The weather on Sept. 3rd for the BOP [email protected] Show was nearly perfect. The smoke 253-845-2288 home 253-576-1128 cell from the wild fires kept the temperature at a tolerable level. -

1970 Revival Glidden Tour

The Silver Anniversary {;jlidden Tour by Henry Austin Clark, Jr. Twenty-five years ago the Clarks headed off Long Island towards Albany for the start of the Fl RST Glidden Tour Revival in a thirty-four old Renault berline, wondering what it would be like, and how much trouble we would encounter. This October we again started off, this time to Mobile, Alabama in a forty-one year old Lincoln sport phaeton. The re spective years of the cars were 1912 and 1929, in cidentally, reflecting a significant change in the cars going on the Tours since the beginning. Oddly enough the 1912 Renault ran like a watch with no brakes, while the 1929 Lincoln gave lots of trouble on the way south, until helping friends made it right. In between the years 1946 and 1970 we have been to lots of places from Maine to the Rockies, and from Canada to Florida on the Tours. We have met many fine people, and have made many good Nelson Deedle of Belleville, Ill. had a French car to go with the' French name of his hometown, a 1927 Bugatti Right, 1931 Cadillac friends, a surprising number of whom we see again cylinder Linvoln. Our route took us under the and again. Every Tour has had its outstanding harbor in a tunnel and right into town to the Admiral scenery and its memorable experiences, including Semmes Hotel and Motor Inn, two related establish· finding a new old car on almost every tour from ments across the street from one another. The older 1946 on. -

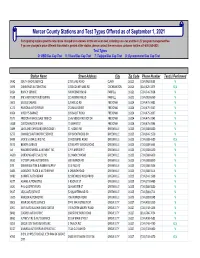

Mercer County Stations and Test Types Offered As of August 1, 2021

Mercer County Stations and Test Types Offered as of September 1, 2021 Participating stations post the retail price charged to customers for the emission test, including sales tax and the $1.57 program management fee. If you are charged a price different from what is posted at the station, please contact the emissions customer hotline at 1-800-265-0921. Test Types O: OBD/Gas Cap Test V: Visual/Gas Cap Test T: Tailpipe/Gas Cap Test D: Dynamometer/Gas Cap Test Station Name Street Address City Zip Code Phone Number Test(s) Performed BV42 SOUTH SHORE SERIVCE 2787 LAKE ROAD CLARK 16113 (724) 962‐0685 V AS96 CUMMINGS AUTOMOTIVE 3398 COUNTY LINE RD COCHRANTON 16314 (814) 425‐1879 O,V D124 BURICH SERVICE 600 ROEMER BLVD FARRELL 16121 (724) 346‐3928 V T638 JIM'S AUTOMOTIVE&TOWING 315 ROEMER BLVD FARRELL 16121 (724) 983‐6260 V 3603 KELSOS GARAGE 129 KELSO RD FREDONIA 16124 (724) 475‐3481 V K173 PARSONS AUTO REPAIR 251 MILL STREET FREDONIA 16124 (724) 475‐4567 V KK64 KIRSCH'S GARAGE 109 BALUT ROAD FREDONIA 16124 (724) 475‐2007 V T675 FREDONIA WHOLESALE TIRE CO 2145 MERCER RD BOX 24 FREDONIA 16124 (724) 475‐3145 V U658 CUSTOM AUTO FINISH 75 GRANT ST FREDONIA 16124 (724) 475‐3346 V 1889 LAKELAND CHRYSLER/JEEP/DODGE I31 HADLEY RD GREENVILLE 16125 (724) 588‐8100 V 6275 SWINGLES AUTOMOTIVE SERVICE 607 BRENTWOOD DR GREENVILLE 16125 (724) 646‐1550 V 8489 JACK'S 5‐STAR CLINIC INC. 19 KIDDSMILL ROAD GREENVILLE 16125 (724) 588‐4600 O,V 9172 BEBOPS GARAGE 670 BEATTY SCHOOL ROAD GREENVILLE 16125 (724) 588‐5063 V A4 WAGNERS WHEEL ALINEMENT INC 179 S MERCER ST -

Table of Cases

Mercer Law Review Volume 44 Number 1 Annual Survey of Georgia Law Article 17 12-1992 Table of Cases Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr Recommended Citation (1992) "Table of Cases," Mercer Law Review: Vol. 44 : No. 1 , Article 17. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr/vol44/iss1/17 This Table of Cases is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mercer Law Review by an authorized editor of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Cases Abacus, Inc. v. Hebron Baptist Church, Inc., Barnes v. Wall, 224 147 Batson-Cook v. Aetna Insurance Co., 255 Abrams v. Abrams, 202 Batterson v. Groves, 199 Abrams & Wofsy v. Renaissance Investment Beasley v. State, 186 Corp., 93 Bell v. Loosier of Albany, Inc., 123 Adams v. D & D Leasing Co., 122 Bennett v. Matt Gay Chevrolet Oldsmobile, Adams v. Perdue, 320 Inc., 426 Aden's Minit Market v. Landon, 483. Bennett v. State, 180 Ailion v. Wade, 48 Benning Construction Co. v. Dykes Paving Alabama v. White, 176 & Construction Co., 148 Allen v. Rome Kraft Co., 48 Beringause v. Fogleman Truck Lines, Inc., Allison v. State, '231 395 Allstate Insurance Co. v. City of Atlanta, Berryhill v. State, 179 402 Bi-Lo, Inc. v. McConnell, 413 Allstate Insurance Co. v. Evans, 261 Birt v. State, 195 Aman v. State, 178 Boehm v. Proctor, 352 American Demolition, Inc. v.