Gray Squirrel (Sciurus Carolinensis) Written by Kristi L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

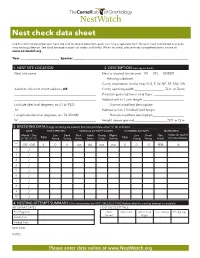

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

The Distribution and Habitat Selection of Introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus Carolinensis, in British Columbia

03_03045_Squirrels.qxd 11/7/06 4:25 PM Page 343 The Distribution and Habitat Selection of Introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, in British Columbia EMILY K. GONZALES Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Forest Sciences Centre, 3004-2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4 Canada Gonzales, Emily K. 2005. The distribution and habitat selection of introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis,in British Columbia. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(3): 343-350. Eastern Grey Squirrels were first introduced to Vancouver in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia in 1909. A separate introduction to Metchosin in the Victoria region occurred in 1966. I surveyed the distribution and habitat selection of East- ern Grey Squirrels in both locales. Eastern Grey Squirrels spread throughout both regions over a period of 30 years and were found predominantly in residential land types. Some natural features and habitats, such as mountains, large bodies of water, and coniferous forests, have acted as barriers to expansion for Eastern Grey Squirrels. Given that urbanization is replacing conifer forests throughout southern British Columbia, it is predicted that Eastern Grey Squirrels will continue to spread as habitat barriers are removed. Key Words: Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, distribution, habitat selection, invasive, British Columbia. The vast majority of introduced species do not suc- such as backyards, parks, and cemeteries (Pasitschniak- cessfully establish populations in novel environments Arts and Bendell 1990). EGS co-occur with North (Williamson 1996). Many successful non-native species American Red Squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) are human comensals which thrive in human-modified throughout much of their range where habitat special- environments (Williamson and Fitter 1996; Sax and ization and not competition determines the differences Brown 2000). -

![The Genome Sequence of the Eastern Grey Squirrel, Sciurus Carolinensis Gmelin, 1788 [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7483/the-genome-sequence-of-the-eastern-grey-squirrel-sciurus-carolinensis-gmelin-1788-version-1-peer-review-2-approved-527483.webp)

The Genome Sequence of the Eastern Grey Squirrel, Sciurus Carolinensis Gmelin, 1788 [Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]

Wellcome Open Research 2020, 5:27 Last updated: 03 SEP 2021 DATA NOTE The genome sequence of the eastern grey squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis Gmelin, 1788 [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Dan Mead 1, Kathryn Fingland 2, Rachel Cripps3, Roberto Portela Miguez 4, Michelle Smith1, Craig Corton1, Karen Oliver1, Jason Skelton1, Emma Betteridge1, Jale Doulcan 1, Michael A. Quail1, Shane A. McCarthy 1, Kerstin Howe 1, Ying Sims1, James Torrance 1, Alan Tracey 1, Richard Challis 1, Richard Durbin 1, Mark Blaxter 1 1Tree of Life, Wellcome Sanger Institute,Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, CB10 1SA, UK 2Nottingham Trent University, School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences, Nottingham, NG25 0QF, UK 3Red Squirrel Officer, The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside, The Barn, Berkeley Drive, Bamber Bridge, Preston, PR5 6BY, UK 4Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, UK v1 First published: 13 Feb 2020, 5:27 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15721.1 Latest published: 13 Feb 2020, 5:27 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15721.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract We present a genome assembly from an individual male Sciurus 1 2 carolinensis (the eastern grey squirrel; Vertebrata; Mammalia; Eutheria; Rodentia; Sciuridae). The genome sequence is 2.82 version 1 gigabases in span. The majority of the assembly (92.3%) is scaffolded 13 Feb 2020 report report into 21 chromosomal-level scaffolds, with both X and Y sex chromosomes assembled. 1. Erik Garrison , University of California, Keywords Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA Sciurus carolinensis, grey squirrel, genome sequence, chromosomal 2. -

Audiogram of the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus Niger)

Journal of Comparative Psychology Copyright 1997 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1997, Vol. 111, No. 1, 1130-104 0735-7036/97/$3.00 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS Audiogram of the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) Laura L. Jackson, Henry E. Heffner, and Rickye S. Heffner Umversity of Toledo The behavioral audiograms of 2 fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) were determined with a conditioned avoidance procedure. The squirrels were able to hear tones ranging from 113 Hz to 49 kHz at a level of 60 dB sound-pressure level or less, with their best sensitivity of 1 dB occurring at 8 kHz. Their ability to hear frequencies below 150 Hz indicates that they have good low-frequency hearing, as do the 2 other members of the squirrel family (black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dogs) for which audiograms are available. This suggests that the ancestral sciurid may also have had good low-frequency hearing. The taxonomic order Rodentia is a varied and successful habitat (cf. R. S. Heffner, Heffner, Contos, & Kearns, group of animals comprising 33 families with more species 1994). Here we present the first audiogram of an arboreal than any other mammalian order. In addition to being dis- rodent, the tree-dwelling fox squirrel, Sciurus niger, and tributed nearly worldwide, these species inhabit many di- compare its hearing with that of other rodents, particularly verse ecological niches, including nocturnal and diurnal, that of other sciurids. predator and prey, arboreal, terrestrial, subterranean, and semiaquatic (Nowak, 1991). They also possess a variety of adaptations for leaping, running, climbing, burrowing, Method swimming, and gliding. In terms of body sizes, rodents The animals were tested with a conditioned avoidance proce- range from small mice weighing less than 10 g to large dure with a water reward (H. -

Risk Analysis of the Fox Squirrel Sciurus Niger

ELGIUM B NATIVE ORGANISMS IN ORGANISMS NATIVE - OF NON OF Risk analysis of the fox squirrel Sciurus niger Updated version, May 2015 ISK ANALYSIS REPORT REPORT ANALYSIS ISK R Risk analysis report of non-native organisms in Belgium Risk analysis of the fox squirrel Sciurus niger Evelyne Baiwy(1), Vinciane Schockert(1) & Etienne Branquart(2) (1) Unité de Recherches zoogéographiques, Université de Liège, B-4000 Liège (2) Cellule interdépartementale sur les Espèces invasives, Service Public de Wallonie Adopted in date of: 11th March 2013, updated in May 2015 Reviewed by : Sandro Bertolino (University of Turin) & Céline Prévot (DEMNA) Produced by: Unité de Recherches zoogéographiques, Université de Liège, B-4000 Liège Commissioned by: Service Public de Wallonie Contact person: [email protected] & [email protected] This report should be cited as: “Baiwy, E.,Schockert, V. & Branquart, E. (2015) Risk analysis of the Fox squirrel, Sciurus niger, Risk analysis report of non-native organisms in Belgium. Cellule interdépartementale sur les Espèces invasives (CiEi), DGO3, SPW / Editions, updated version, 34 pages”. Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 1 Rationale and scope of the Belgian risk analysis scheme ..................................................................... 2 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................ -

The Use of GIS and Modelling Approaches in Squirrel Population Management and Conservation: a Review

SPECIAL SECTION: ARBOREAL SQUIRRELS The use of GIS and modelling approaches in squirrel population management and conservation: a review P. W. W. Lurz1,*, J. L. Koprowski2 and D. J. A. Wood2 1School of Biology and Psychology, IRES, Devonshire Building, University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK 2Wildlife Conservation and Management, School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA We review modelling approaches in relation to three cosmopolitan distribution. Squirrels are managed as game key areas of sciurid ecology: management, disease risk or fur-bearers that provide considerable subsistence and 5 6 assessments and conservation. Models enable us to ex- economic value , especially in Holarctic species . Tree plore different scenarios to develop effective manage- squirrels are also viewed as pests in many regions, attack- ment and conservation strategies. They may also assist ing crops, trees and electrical systems or competing with in identifying and targeting research needs for tree native species6–8. Modelling in a natural resources man- and flying squirrels. However, there is a need to refine agement context has usually focused on habitat-based techniques and assure that data used are applicable at methods and harvest dynamics. the appropriate scale. Models allow managers to make Habitat-based models have been applied to two common informed decisions to help conserve species, but suc- species of North America, eastern fox squirrels (S. niger) cess requires that the utility of the tool be evaluated as 9–11 new empirical data become available and models re- and eastern grey squirrels . Models identify habitat in fined to more accurately meet the needs of current terms of two relatively simple components: winter food conservation scenarios. -

Bird Nests What Is a Bird's Nest?

Duke Gardens Winter Fun at Home BIRD NESTS Winter can be a good time to spot bird nests in bare tree branches that lost their leaves in the fall. Have you ever spotted any bird nests or squirrel dreys in a tree? (Drey is the word for a squirrel nest, and they usually look like a messy ball of sticks and leaves). WHAT IS A BIRD’S NEST? All birds start their life cycle as an egg. Eggs need to be protected from weather and predators. An egg also needs to stay warm from the time it is laid until it hatches. This is called the incubation period. A nest is the shelter most adult birds build to protect their eggs until A squirrel drey they hatch and to keep baby birds safe until they are ready to leave (not a bird nest!) the nest. Nests range in size, shape, location and building materials, and all of these can be clues about the kind of bird that made it. For example, bald eagle nests can be 5-6 feet across, while a cardinal’s nest is about 4 inches across. Hummingbird nests can be as small as a thimble when they are built, but they are made with materials that allow the nest to stretch as the baby birds inside it grow. Nests can be built in many places. Some birds make cavity nests inside something by finding or making an opening inside a tree, a stump or a nest box. Carolina wrens, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and some owls are a few examples of cavity nesting birds. -

Sciurid Phylogeny and the Paraphyly of Holarctic Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31 (2004) 1015–1030 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Sciurid phylogeny and the paraphyly of Holarctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus) Matthew D. Herron, Todd A. Castoe, and Christopher L. Parkinson* Department of Biology, University of Central Florida, 4000 Central Florida Blvd., Orlando, FL 32816-2368, USA Received 26 May 2003; revised 11 September 2003 Abstract The squirrel family, Sciuridae, is one of the largest and most widely dispersed families of mammals. In spite of the wide dis- tribution and conspicuousness of this group, phylogenetic relationships remain poorly understood. We used DNA sequence data from the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of 114 species in 21 genera to infer phylogenetic relationships among sciurids based on maximum parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic methods. Although we evaluated more complex alternative models of nucleotide substitution to reconstruct Bayesian phylogenies, none provided a better fit to the data than the GTR + G + I model. We used the reconstructed phylogenies to evaluate the current taxonomy of the Sciuridae. At essentially all levels of relationships, we found the phylogeny of squirrels to be in substantial conflict with the current taxonomy. At the highest level, the flying squirrels do not represent a basal divergence, and the current division of Sciuridae into two subfamilies is therefore not phylogenetically informative. At the tribal level, the Neotropical pygmy squirrel, Sciurillus, represents a basal divergence and is not closely related to the other members of the tribe Sciurini. At the genus level, the sciurine genus Sciurus is paraphyletic with respect to the dwarf squirrels (Microsciurus), and the Holarctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus) are paraphyletic with respect to antelope squirrels (Ammosper- mophilus), prairie dogs (Cynomys), and marmots (Marmota). -

Sciurus Meridionalis (Rodentia, Sciuridae)

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 28 (1): 1–8, 2017 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it doi:10.4404/hystrix–28.1-12015 Research Article New endemic mammal species for Europe: Sciurus meridionalis (Rodentia, Sciuridae) Lucas A. Wauters1,∗, Giovanni Amori2, Gaetano Aloise3, Spartaco Gippoliti4, Paolo Agnelli5, Andrea Galimberti6, Maurizio Casiraghi6, Damiano Preatoni1, Adriano Martinoli1 1Environment Analysis and Management Unit - Guido Tosi Research Group, Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, Università degli Studi dell’Insubria, Via J. H. Dunant 3, 21100 Varese (Italy) 2CNR - Institute of Ecosystem Studies, c/o Department of Biology and Biotechnology “Charles Darwin”, Sapienza - Rome University, Viale dell’Università 32, 00185 Roma (Italy) 3Museo di Storia Naturale della Calabria ed Orto Botanico, Università della Calabria, Via Savinio – Edificio Polifunzionale, 87036 Rende (CS) (Italy) 4Società Italiana per la Storia della Fauna “G. Altobello”, Viale Liegi 48, 00198 Roma (Italy) 5Museo di Storia Naturale, Università di Firenze, Sezione di Zoologia “La Specola”, Via Romana 17, 50125 Firenze (Italy) 6ZooPlantLab, Dipartimento di Biotecnologie e Bioscienze, Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 2, 20126 Milano (Italy). Keywords: Abstract Sciurus meridionalis squirrels Combining genetic, morphological and geographical data, we re-evaluate Sciurus meridionalis, Southern Italy Lucifero 1907 as a tree squirrel species. The species, previously considered a subspecies of the endemic species Eurasian red squirrel, Sciurus vulgaris, is endemic to South Italy with a disjunct distribution with respect to S. vulgaris. The new species has a typical, monomorphic coat colour characterized by Article history: a white ventral fur and a very dark-brown to blackish fur on the back, sides and tail. -

Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus Carolinensis

eastern gray squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern gray squirrel’s head-body length is Class: Mammalia between eight and 11 inches, with its tail about the Order: Rodentia same length as the body. Its body fur is gray, and there is a border of white fur on the bushy, gray tail. Family: Sciuridae The belly fur is white, a cream line surrounds each ILLINOIS STATUS eye, and white tips are present on the back of the ears. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern gray squirrel may be found statewide in Illinois. It lives in woods or forests that have a closed canopy, nut-bearing trees and plenty of cavity trees. As these mature forests have been destroyed in Illinois, the population of gray squirrels has declined. However, gray squirrels are common in cities. Here, they live in trees without the conditions described above. The gray squirrel eats buds, leaves, fruits, berries, fungi, pecans, acorns, hickory nuts, tree bark, walnuts and the seeds of various other trees. It stores nuts in holes in the ground. This squirrel grasps food in its front paws. It is primarily arboreal, and its large, bushy tail helps it balance while climbing and resting in trees. Urban squirrels are good at climbing brick walls and walking along wires and cables. The eastern gray squirrel does not hibernate and is active during the day year-round. It ILLINOIS RANGE may sleep for several consecutive days in winter, however. Its call is “kuk-kuk-cut-cut-cut.” This animal builds a leaf nest in the high branches of a tree but may use a tree cavity for escape from predators and poor weather and for raising its young. -

Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol

CANADA GOOSE EGG ADDLING PROTOCOL The Humane Society of the United States Wild Neighbors Program 2100 L Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 (202) 452-1100 humanesociety.org/wildlife January 2009 ©The Humane Society of the United States. The HSUS Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol January 2009 Introduction Addling means “loss of development.” It commonly refers to any process by which an egg ceases to be viable. Addling can happen in nature when incubation is interrupted for long enough that eggs cool and embryonic development stops. People addle where they want to manage bird populations. Population management should be only one component of a comprehensive, integrated, humane program to resolve conflict between people and wild Canada geese (see Humanely Resolving Conflicts with Canada Geese: a Guide for Urban and Suburban Property Owners and Communities available online at humanesociety.org/wildlife). A contraceptive drug, nicarbazin sold under the brand name OvoControl (online at ovocontrol.com), reduces hatching to manage populations humanely. Geese who consume an adequate dose during egg production lay infertile eggs. Managing populations with OvoControl requires less labor than addling as you do not have to find and treat individual nests. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has registered this drug in the United States. A U.S Fish and Wildlife Agency (USFWS) permit is required. Potential users should also check to see if their state wildlife agencies require an additional permit. Complete contact information for the supplier is at the end of this Protocol. This Protocol is for Canada geese (Branta canadensis spp.) only. Other species of birds have different nesting chronologies and incubation periods that make appropriate addling different. -

Starlings and Mynas

Beneficial Starlings The Eurasian Rose-colored and African Wattled Starlings are believed Starlings to be beneficial due to their insect con trol near agricultural crops. Both species establish breeding colonies in and Mynas areas where swarms of locusts and by Susan Congdon, grasshoppers appear. It is believed that Disney's Animal Kingdom, FL they eat enough of these insects to protect food crops. banded and released have been sub Pest Starlings? he names starling and myna sequently recovered when found for There are some species of star are often used interchange sale in Indonesian bird markets. The ling/myna that are considered to be T ably similar to pigeoN. and conversion of forest to agricultural pests. The European Starling and dove. Myna is the Hindi word for star land, and deforestation for firewood Common Myna are two examples of ling and is often used for species native and human settlements have greatly this. European Starlings were intro to southern and southeastern Asia and decreased their natural habitat. duced to North America and are the southeastern Pacific. Many of the In response to the decreasing wild extremely gregarious. As well as dam Asian birds are known as both starlings population, the American Zoo and aging important crops they compete and mynas. Aquarium Association, Jersey Wildlife with native birds for hollows in which Preservation Trust, and the Indonesian to nest. Near Extinction ofthe Bali Myna government have set up a Species Common Mynas, introduced to There are 114 species in the Survival Program (SSP). The main goals many places including Hawaii and sturnidae family.