Later Egypt Years (930–31/1524–25) 287

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E

Turan EBRU TURAN Fordham University-Rose Hill 441 E. Fordham Road, Dealy 620 Bronx NY, 10458 [email protected] (718-817-4528) EDUCATION University of Chicago, Ph.D., Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, March 2007 Bogazici University, B.A., Business Administration, 1997 Bogazici University, B.A., Economics, 1997 EMPLOYMENT Fordham University, History Department, Assistant Professor, Fall 2006-Present Courses Thought: Introduction to Middle East History, History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1923), Religion and Politics in Islamic History University of Chicago, Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Graduate Lecturer, 2003-2005 Courses Thought: Ottoman Turkish I, II, III; History of the Ottoman Empire (1300-1700); Islamic Political Thought (700-1550) GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Visiting Research Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, University of Texas-Austin, 2008-2009 Grant to attend the Folger Institute's Faculty Weekend Seminar,"Constantinople/Istanbul: Destination, Way-Station, City of Renegades," September 2007 Dissertation Write-Up Grant, Division of Humanities, Franke Institute for the Humanities, University of Chicago, 2005-2006 Grant to participate in Mellon Summer Institute in Italian Paleography Program, Newberry Library, Summer 2005 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2004 Overseas Dissertation Research Fellowship, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 2003 American Research Institute in Turkey Dissertation Grant, 2002-2003 Turkish Studies Grant, University of Chicago, Summer 2002 Doctoral Fellow in Sawyer Seminar on Islam 1300-1600, Franke Institute for Humanities, University of Chicago, 2001-2002 Tuition and Stipend, Division of Humanities, University of Chicago, 1997-2001 PUBLICATIONS Articles: “Voice of Opposition in the Reign of Sultan Suleyman: The Case of Ibrahim Pasha (1523-1536),” in Studies on Istanbul and Beyond: The Freely Papers, Volume I, ed. -

ALBANIAN SOLDIERS in the OTTOMAN ARMY DURING the GREEK REVOLT at 1821 Ali Fuat ÖRENÇ

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Epoka University IBAC 2012 vol.2 ALBANIAN SOLDIERS IN THE OTTOMAN ARMY DURING THE GREEK REVOLT AT 1821 ∗∗ Ali Fuat ÖRENÇ Introduction Ottoman Army organization had started to deteriorate from the mid-17th century. Military failures made the social and economic problems worse. In this situation, alternative potentials in the empire appeared because of the increasing military needs of the central government and the provincial governors. By the way, general employment of the Albanian warriors who were famous with their courage and strength became possible.1 There were a lot of reasons for employing Albanian warriors with salary while there was Ottoman regular army corps, including janissaries and soldiers from the states. Governing problems, had existed in the states and land system after the defeat in Vienne at 1683, was one of these reasons. Also after the end of the conquering era, the castles and fortresses at the borderlines were built for defense and there were not a necessary number of soldiers in these buildings. This problem was tried to by employing the warriors with long- matchlock-guns from Bosnia, Herzegovina and Albania.2 During the time, the necessity of mercenary increased too much as seen in the example of the Ottoman army which established for pressing the Greek Revolt in 1821, was almost composed of the Albanian soldiers.3 There were historical reasons for choosing Albanian soldiers in the Balkans. A strong feudal-system had existed in the Albanian lands before the Ottoman rule. This social structure, which consisted of the local connections and obedience around the lords, continued by integrating, first, timar (fief) system after the Ottoman conquest in 1385 and then, devshirme system. -

The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide During World War I, the Ottoman Empire carried out what most international experts and historians have concluded was one of the largest genocides in the world's history, slaughtering huge portions of its minority Armenian population. In all, over 1 million Armenians were put to death. To this day, Turkey denies the genocidal intent of these mass murders. My sense is that Armenians are suffering from what I would call incomplete mourning, and they can't complete that mourning process until their tragedy, their wounds are recognized by the descendants of the people who perpetrated it. People want to know what really happened. We are fed up with all these stories-- denial stories, and propaganda, and so on. Really the new generation want to know what happened 1915. How is it possible for a massacre of such epic proportions to take place? Why did it happen? And why has it remained one of the greatest untold stories of the 20th century? This film is made possible by contributions from John and Judy Bedrosian, the Avenessians Family Foundation, the Lincy Foundation, the Manoogian Simone Foundation, and the following. And others. A complete list is available from PBS. The Armenians. There are between six and seven million alive today, and less than half live in the Republic of Armenia, a small country south of Georgia and north of Iran. The rest live around the world in countries such as the US, Russia, France, Lebanon, and Syria. They're an ancient people who originally came from Anatolia some 2,500 years ago. -

Pax Britannica and the Anti-Systemic Movement of Viceroy Mehmet Ali Pasha of Egypt

PAX BRITANNICA AND THE ANTI-SYSTEMIC MOVEMENT OF VICEROY MEHMET ALI PASHA OF EGYPT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY OKYANUS AKIN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS DECEMBER 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Oktay Tanrısever Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. M. Fatih Tayfur Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. M. Fatih Tayfur (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Çınar Özen (Ankara Uni., IR) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Okyanus Akın Signature: iii ABSTRACT PAX BRITANNICA AND THE ANTI-SYSTEMIC MOVEMENT OF VICEROY MEHMET ALI PASHA OF EGYPT Akın, Okyanus M.S., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. M. Fatih Tayfur December 2019, 234 pages The Pax Britannica, as a system, defined the political-economy of the nineteenth century. -

Orhan Kolog˘Lu RENEGADES and the CASE ULUÇ/KILIÇ ALI ·

Orhan Kolog˘lu RENEGADES AND THE CASE · ULUÇ/KILIÇ ALI In the history of the Mediterranean region, the Renegade of the Christians who becomes a Mühtedi by joining the Muslim religion, has played an important role. In European languages the Renegade is the person who abandons Christianity for a different faith. The Mühtedi, on the other hand, according to Muslim and Turkish communities, is the person of another faith who embraces Islam. Since Islam began to spread 600 years after Christianity, it gathered its early followers among pagans, a few Jews but especially Christians. Its rapid spread over Syria, Egypt, North Africa, Sicily, Spain and into central France indicates that all Mediterranean communities were largely affected by the religion. Christianity, which had become the domineering and ruling faith through Papacy and the Byzantine Empire, was now lar- gely disturbed by this competitor. For this reason, it was only natural that both sides scrutinized the Renegade/Mühtedi very closely. The concern of one side in losing a believer matched the concern of the other side in preventing the loss of the Mühtedi, who is then called a Mürted (apostate, the verb is irtidad). European research on this subject outweighs the research done by Muslims, because renegades had not only been, quantitative-wise, many times more than mürteds, but also they played more important roles as history-makers in the Mediterranean. Muslim indifference to their past is easily understandable because the interest was focused only on their activities as Muslims. However, European research bears the mark of the Christian perspective and has a reactionary approach. -

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

On the Fall of Constantinople

On the Fall of Constantinople From the Diaries Nicolo Barbo, https://deremilitari.org/2016/08/the-siege-of-constantinople-in-1453-according-to-nicolo-barbaro/ accessed 17 November 2017. On the twenty-ninth of May, the last day of the siege, our towards the walls, so that they had the choice of dying on Lord God decided, to the sorrow of the Greeks, that He one side or the other; and when this first group was killed was willing for the city to fall on this day into the hands of and cut to pieces, the second group began to attack Mahomet Bey the Turk son of Murat, after the fashion and vigorously. The first group was sent forward for two in the manner described below; and also our eternal God reasons, firstly because they preferred that Christians was willing to make this decision in order to fulfill all the should die rather than Turks, and secondly to wear us out ancient prophecies, particularly the first prophecy made by in the city; and as I have said, when the first group was Saint Constantine, who is on horseback on a column by dead or wounded, the second group came on like lions the Church of Saint Sophia of this city, prophesying with unchained against the walls on the side of San Romano; his hand and saying, “From this direction will come the and when we saw this fearful thing, at once the tocsin was one who will undo me,” pointing to Anatolia, that is sounded through the whole city and at every post on the Turkey. -

Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland As Cultural Mediators

Chapter 10 Connectivity, Mobility, and Mediterranean “Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland as Cultural Mediators Gülru Necipoğlu Considering the mobility of persons and stones is one way to reflect upon how movable or portable seemingly stationary archaeological sites might be. Dalmatia, here viewed as a center of gravity between East and West, was cen- tral for the global vision of Ottoman imperial ambitions, which peaked during the 16th century. Constituting a fluid “border zone” caught between the fluctu- ating boundaries of three early modern empires—Ottoman, Venetian, and Austrian Habsburg—the Dalmatian coast of today’s Croatia and its hinterland occupied a vital position in the geopolitical imagination of the sultans. The Ottoman aspiration to reunite the fragmented former territories of the Roman Empire once again brought the eastern Adriatic littoral within the orbit of a tri-continental empire, comprising the interconnected arena of the Balkans, Crimea, Anatolia, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa. It is important to pay particular attention to how sites can “travel” through texts, drawings, prints, objects, travelogues, and oral descriptions. To that list should be added “traveling” stones (spolia) and the subjective medium of memory, with its transformative powers, as vehicles for the transmission of architectural knowledge and visual culture. I refer to the memories of travelers, merchants, architects, and ambassadors who crossed borders, as well as to Ottoman pashas originating from Dalmatia and its hinterland, with their extraordinary mobility within the promotion system of a vast eastern Mediterranean empire. To these pashas, circulating from one provincial post to another was a prerequisite for eventually rising to the highest ranks of vizier and grand vizier at the Imperial Council in the capital Istanbul, also called Ḳosṭanṭiniyye (Constantinople). -

Egypt's Finances and Foreign Campaigns, 1810-1840. by 1 Ali A

Egypt's Finances and Foreign Campaigns, 1810-1840. by 1 Ali A. Soliman, Visiting Professor, Cairo University0F , and M. Mabrouk Kotb, Assoc. Professor, Fayoum University, Egypt. I. Introduction: In May 1805 Egypt selected for the first time in its long history a ruler of its own choice. "Muhammad Ali Pasha" was chosen by the Cairo intellectuals (Ulemas) and community leaders to rule them after a long period of turmoil following the departure of the French forces who tried to subjugate Egypt, 1798-1801. The expulsion of the French from Egypt was the result of three supporting forces, the Ottomans who had ruled Egypt since 1517, the British, who would not allow the French to threaten their route to India, and the Egyptian nationals who staged two costly revolts which made the continuation of French presence untenable. Although "Muhammad Ali" had served in the Ottoman army which was sent to regain Egypt, he was willing to accept the peoples' mandate to rule them fairly and according to their wishes (Al- Jabbarti, 1867) and (Dodwell, 1931). Such an accord was not accepted by the Ottomans, and the British alike. The first tried to remove him to another post after one year of his rule. Again, popular support and the right amount of bribes to the Sultan and his entourage assured his continuation as "Waly" (viceroy) of Egypt. A year later, the British sent an occupying force under "Frasier" that was defeated, a short distance of its landing in Alexandria, near Rosetta (1807). For most of the years of his long reign, 1805- 1848, "Muhammad Ali Pasha" (we shall refer to him also as the Pasha) had to engage in five major wars to solidify his position as a ruler of Egypt. -

Akademik Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, Yıl: 5, Sayı: 41, Mart 2017, S. 269-279 Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Article Arrival Date

_____________________________________________________________________________________ Akademik Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, Yıl: 5, Sayı: 41, Mart 2017, s. 269-279 Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Article Arrival Date Yayınlanma Tarihi / The Publication Date 31.12.2016 02.03.2017 Dr. Celal EMANET Garden State İslamic Center, İslam Tarihi [email protected] “ISLAMLASHMAQ” TERM IN SAID HALIM PASHA Abstract Beginning in the late eighteenth century, Ottoman Empire became the first Muslim state to reform its administrative, educational, military, and eventually the political systems. Reformist thinkers who grew up during the late Ottoman era who pro- duced their work during the republican period constitute the first generation of these post-Ottoman reformist thinkers. A respected statesman and diplomat, Said Halim Pasha was first and foremost an influential thinker, one of the most out- spoken representatives of the Islamist school during the Second Constitutional Pe- riod (1908-1920). In his famous work entitled lslamization (Islamlashmaq), Said Halim proposes a complete Islamization of Muslim society, which includes forget- ting their pre-Islamic past and purifying themselves of their pre-Islamic heritage. This study will be focused on Said Halim Pasha’s views of politics relating to Is- lamization. Keywords: Said Halim Pasha, Islamlashmaq, Imitate, Westernisation, Religion. “Islamlashmaq” Term In Saıd Halım Pasha SAİD HALİM PAŞA’DA “İSLAMLAŞMAK” TERİMİ Öz XVIII. yüzyılın son çeyreğinde Osmanlı İmparatorluğu yönetim, eğitim, askeri ve nihayetinde de politik alanlarda reformlar uygulayan ilk Müslüman devlettir. Os- manlı Devleti’nin son yüz yılında yaşamış pek çok reformist düşünce adamı vardır ki; onlar meşrutiyet döneminin hazırlayıcıları ve Osmanlı sonrası reformistlerinin ilk jeneresyonudur. Osmanlı Devleti son dönem sadrazamlarından, II. Meşrutiyet döneminde (1908-1920) İslamcılık fikrini temsil eden ve bu fikirlerini açık bir şekilde savunan Said Halim Paşa görüşleri ile dikkat çeken bir devlet adamıdır. -

Said Halim Pasha: an Ottoman Statesman and an Islamist Thinker (1865-1921)

SAID HALIM PASHA: AN OTTOMAN STATESMAN AND AN ISLAMIST THINKER (1865-1921) by Ahmet ~eyhun A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University Montreal January 2002 ©Ahmet ~eyhun 2002 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisisitons et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-612-88699-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-612-88699-9 The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou aturement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ln compliance with the Canadian Conformément à la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privée, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this dissertation. -

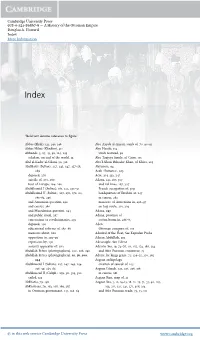

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago