Trans-Neptunian Objects As Natural Probes to the Unknown Solar System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Deeper Look at the Colors of the Saturnian Irregular Satellites Arxiv

A deeper look at the colors of the Saturnian irregular satellites Tommy Grav Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, MS51, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA02138 and Instiute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Dr., Honolulu, HI86822 [email protected] James Bauer Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 4800 Oak Grove Dr., MS183-501, Pasadena, CA91109 [email protected] September 13, 2018 arXiv:astro-ph/0611590v2 8 Mar 2007 Manuscript: 36 pages, with 11 figures and 5 tables. 1 Proposed running head: Colors of Saturnian irregular satellites Corresponding author: Tommy Grav MS51, 60 Garden St. Cambridge, MA02138 USA Phone: (617) 384-7689 Fax: (617) 495-7093 Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract We have performed broadband color photometry of the twelve brightest irregular satellites of Saturn with the goal of understanding their surface composition, as well as their physical relationship. We find that the satellites have a wide variety of different surface colors, from the negative spectral slopes of the two retrograde satellites S IX Phoebe (S0 = −2:5 ± 0:4) and S XXV Mundilfari (S0 = −5:0 ± 1:9) to the fairly red slope of S XXII Ijiraq (S0 = 19:5 ± 0:9). We further find that there exist a correlation between dynamical families and spectral slope, with the prograde clusters, the Gallic and Inuit, showing tight clustering in colors among most of their members. The retrograde objects are dynamically and physically more dispersed, but some internal structure is apparent. Keywords: Irregular satellites; Photometry, Satellites, Surfaces; Saturn, Satellites. 3 1 Introduction The satellites of Saturn can be divided into two distinct groups, the regular and irregular, based on their orbital characteristics. -

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

" Tnos Are Cool": a Survey of the Trans-Neptunian Region VI. Herschel

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. classicalTNOsManuscript c ESO 2012 April 4, 2012 “TNOs are Cool”: A survey of the trans-Neptunian region VI. Herschel⋆/PACS observations and thermal modeling of 19 classical Kuiper belt objects E. Vilenius1, C. Kiss2, M. Mommert3, T. M¨uller1, P. Santos-Sanz4, A. Pal2, J. Stansberry5, M. Mueller6,7, N. Peixinho8,9 S. Fornasier4,10, E. Lellouch4, A. Delsanti11, A. Thirouin12, J. L. Ortiz12, R. Duffard12, D. Perna13,14, N. Szalai2, S. Protopapa15, F. Henry4, D. Hestroffer16, M. Rengel17, E. Dotto13, and P. Hartogh17 1 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, Postfach 1312, Giessenbachstr., 85741 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Konkoly Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1525 Budapest, PO Box 67, Hungary 3 Deutsches Zentrum f¨ur Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V., Institute of Planetary Research, Rutherfordstr. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany 4 LESIA-Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Univ. Paris-Diderot, France 5 Stewart Observatory, The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85721, USA 6 SRON LEA / HIFI ICC, Postbus 800, 9700AV Groningen, Netherlands 7 UNS-CNRS-Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur, Laboratoire Cassiope´e, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 04, France 8 Center for Geophysics of the University of Coimbra, Av. Dr. Dias da Silva, 3000-134 Coimbra, Portugal 9 Astronomical Observatory of the University of Coimbra, Almas de Freire, 3040-04 Coimbra, Portugal 10 Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cit´e, 4 rue Elsa Morante, 75205 Paris, France 11 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, CNRS & Universit´ede Provence, 38 rue Fr´ed´eric Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France 12 Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa (CSIC), Camino Bajo de Hu´etor 50, 18008 Granada, Spain 13 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via di Frascati, 33, 00040 Monte Porzio Catone, Italy 14 INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Salita Moiariello 16, 80131 Napoli, Italy 15 University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA 16 IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, 77 av. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

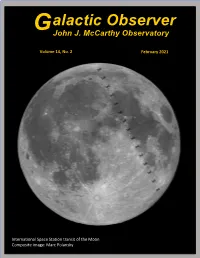

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Should Earth Get Demoted from Planet Status Just Like Pluto?

IOSR Journal of Applied Physics (IOSR-JAP) e-ISSN: 2278-4861.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. I (May. – June. 2018), PP 15-19 www.iosrjournals.org Should Earth Get Demoted From Planet Status Just Like Pluto? Dipak Nath Assistant Professor, HOD, Department of Physics, Sao Chang Govt College, Tuensang;Nagaland, India. Corresponding Author: Dipak Nath Abstract: Clyde.W. Tombough discovered Pluto on march13, 1930. From its discovery in 1930 until 2006, Pluto was classified as Planet. In the late 20th and early 21st century, many objects similar to Pluto were discovered in the outer solar system, notably the scattered disc object Eris in 2005, which is 27% more massive than Pluto. On august-24, 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) defined what it means to be a Planet within the solar system. This definition excluded Pluto as a Planet added it as a member of the new category “Dwarf Planet” along with Eris and Ceres. There were many reasons why Pluto got demoted to dwarf planet status, one of which was that it couldn't clear its orbit of asteroids and other debris. But Earth's orbit is also crowded...too crowded for Earth to be a planet? Earth is indeed in a very crowded orbit, surrounded by tens of thousands of asteroids and other objects. The presence of so many asteroids seems like a serious problem for Earth's claim that it has cleared its neighborhood. And Earth isn't alone in this problem - Jupiter is surrounded by some 100,000 Trojan asteroids, and there's similar clutter around Mars and Neptune. -

Occultations of HIP and UCAC2 Stars Downto 15M by Large TNO in 2004

Astronomy Letters, 2004, vol. 30. Translated from Pis’ma v Astronomicheskij Zhurnal. Occultations of HIP and UCAC2 stars downto 15m by large TNO in 2004-2014 © 2004 D.V. Denissenko Space Research Institute (IKI), Moscow, Russia Received 27 February 2004 Occultations of stars brighter than 15m by largest TNOs are predicted. Search was performed using the following catalogues: Hipparcos; Tycho2 with coordinates of 2838666 stars taken from UCAC2 (Herald, 2003); UCAC2 (Zacharias et al., 2003) with 16356096 stars between 12.00 and 14.99 mag to the north from -45 declination. Predictions were made for 17 largest numbered transneptunian asteroids, recently discovered 2004 DW and 4 known binary Kuiper Belt objects. 64 events occuring at solar elongation of 30° and more are selected, including exceptionally rare occultation m of 6.5 star by double (66652) 1999 RZ253 on 2007 October 4th. Observations of these events by all available means are extremely important since they can provide unique information about the size of TNOs and improve their orbits dramatically. INTRODUCTION OCCULTATIONS BY TNO Over 800 Transneptunian Objects (TNO) are TNOs are typically at 30-50 AU distances discovered since 1992 with 67 of them being from the Earth corresponding to 0.2"-0.3" numbered and 7 having proper names as of parallax. This means that occultation will February 2004. No reliable measurements only happen somewhere on the Earth if the of their sizes have been obtained so far. geocentric path of the object passes within Angular sizes even of the largest objects are 200-300 mas from the star. Combined with arXiv:astro-ph/0403002 28 Feb 2004 about 0.04"±0.01" (Quaoar) which is at the a very slow angular motion of TNO (0.1-1 limit of Hubble Space Telescope resolution. -

Distant Ekos: 2012 BX85 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG

Issue No. 79 February 2012 r ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 8 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Newsletter Information .............................. .....9 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There was 1 new TNO discovery announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2012 BX85 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG Objects recently assigned numbers: 2010 EP65 = (312645) 2008 QD4 = (315898) 2010 EN65 = (316179) 2008 AP129 = (315530) Objects recently assigned names: 1997 CS29 = Sila-Nunam Current number of TNOs: 1249 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 337 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 8 Out of a total of 1594 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 624 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 316 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS The Dynamical Evolution of Dwarf Planet (136108) Haumea’s Collisional Family: General Properties and Implications for the Trans-Neptunian Belt Patryk Sofia Lykawka1, Jonathan Horner2, Tadashi Mukai3 and Akiko M. Nakamura3 1 Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Japan 2 Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Australia 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kobe University, Japan Recently, the first collisional family was identified in the trans-Neptunian belt (otherwise known as the Edgeworth-Kuiper belt), providing direct evidence of the importance of collisions between trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). -

Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael

an Educator’s Guid E INSIDE • Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael For The TeaCher About This Guide .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Connections to Education Standards ................................................................................................... 5 Show Synopsis .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Meet the “Stars” of the Show .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction to Exoplanets: The Basics .................................................................................................. 9 Delving Deeper: Teaching with the Show ................................................................................................13 Glossary of Terms ..........................................................................................................................................24 Online Learning Tools ..................................................................................................................................26 Exoplanets in the News ..............................................................................................................................27 During -

ÉRIS Thèmes De Sa Découverte

Carmela Di Martine – Juin 2020 ÉRIS Thèmes de sa découverte Astronomie La première prise de cliché de l’astre date du 3 septembre 1954 au Mont Palomar en Californie. Éris a été ensuite photographiée lors d’observations effectuées le 21 octobre 2003, avec le télescope Oschin du Mont Palomar par l’équipe de Mike Brown, Chadwick Trujillo et David Rabinowitz. Mais ce n’est en fait que le 5 janvier 2005 qu’elle fut vraiment découverte, lorsque des photographies du même pan de ciel révélèrent son déplacement. Éris et Dysnomie Sous la désignation provisoire 2003 UB313 est officiellement classé « planète naine » le 24 août 2006 par l’Union astronomique internationale. Après avoir été désignée sous différents noms (Xena, Lila, Perséphone, Érèbe...), le « choix » final de la dénomination d’Éris par l’UAI, le 13 septembre 2006, évoque aussi d’une part les discussions et controverses acharnées entre scientifiques sur la remise en cause de la définition du mot « planète » du fait de sa découverte, et d’autre part, l’apparente diversité des orbites des objets épars de cette zone du Système solaire (au-delà de la ceinture de Kuiper) par rapport aux orbites régulières des planètes plus proches du Soleil (jusqu’à Neptune). Sa désignation scientifique officielle complète est (136199) Éris. Pour les principales caractéristiques d’Éris, lire aussi mon article : « Les planètes » (p. 25-27). Astrologie N’aurait-on pas une vision "patriarcale" d’Éris ? Éris la "semeuse de Discordes"… Éris, "l’Emmerdeuse"… Expressions très, trop facilement accordées aussi aux femmes par les hommes… Car des questions se posent tout de même… Pourquoi n’est-ce pas Thétis la « plus Belle » en ce jour de son mariage ? Pourquoi le choix d’Aphrodite embarrasse tant toute l’Assemblé divine qui n’en est pourtant pas habituellement à une guerre près ? Contre toute attente, les thèmes de découvertes d’Éris vont nous dévoiler en effet une toute autre vérité…. -

Binary Asteroids and the Formation of Doublet Craters

ICARUS 124, 372±391 (1996) ARTICLE NO. 0215 Binary Asteroids and the Formation of Doublet Craters WILLIAM F. BOTTKE,JR. Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Mail Code 170-25, Pasadena, California 91125 E-mail: [email protected] AND H. JAY MELOSH Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 Received April 29, 1996; revised August 14, 1996 found we could duplicate the observed fraction of doublet cra- At least 10% (3 out of 28) of the largest known impact craters ters found on Earth, Venus, and Mars. Our results suggest on Earth and a similar fraction of all impact structures on that any search for asteroid satellites should place emphasis Venus are doublets (i.e., have a companion crater nearby), on km-sized Earth-crossing asteroids with short-rotation formed by the nearly simultaneous impact of objects of compa- periods. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. rable size. Mars also has doublet craters, though the fraction found there is smaller (2%). These craters are too large and too far separated to have been formed by the tidal disruption 1. INTRODUCTION of an asteroid prior to impact, or from asteroid fragments dispersed by aerodynamic forces during entry. We propose that Two commonly held paradigms about asteroids and some fast rotating rubble-pile asteroids (e.g., 4769 Castalia), comets are that (a) they are composed of non-fragmented after experiencing a close approach with a planet, undergo tidal chunks of rock or rock/ice mixtures, and (b) they are soli- breakup and split into multiple co-orbiting fragments. -

Humanity and Space

10/17/2012!! !!!!!! Project Number: MH-1207 Humanity and Space An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by: Matthew Beck Jillian Chalke Matthew Chase Julia Rugo Professor Mayer H. Humi, Project Advisor Abstract Our IQP investigates the possible functionality of another celestial body as an alternate home for mankind. This project explores the necessary technological advances for moving forward into the future of space travel and human development on the Moon and Mars. Mars is the optimal candidate for future human colonization and a stepping stone towards humanity’s expansion into outer space. Our group concluded space travel and interplanetary exploration is possible, however international political cooperation and stability is necessary for such accomplishments. 2 Executive Summary This report provides insight into extraterrestrial exploration and colonization with regards to technology and human biology. Multiple locations have been taken into consideration for potential development, with such qualifying specifications as resources, atmospheric conditions, hazards, and the environment. Methods of analysis include essential research through online media and library resources, an interview with NASA about the upcoming Curiosity mission to Mars, and the assessment of data through mathematical equations. Our findings concerning the human aspect of space exploration state that humanity is not yet ready politically and will not be able to biologically withstand the hazards of long-term space travel. Additionally, in the field of robotics, we have the necessary hardware to implement adequate operational systems yet humanity lacks the software to implement rudimentary Artificial Intelligence. Findings regarding the physics behind rocketry and space navigation have revealed that the science of spacecraft is well-established.