1 a Critical Analysis of the Modern Standards Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partnering with Fairfax County Public Schools

FATE Annual Report School Year 2019-2020 Partnering with Fairfax County Public Schools Special points of interest: LOT 9 SOLD FOR $960,000! • Lot 9 was sold for $960,000 • Lot 10 targeted market date On April 17, 2020, FATE sold students are involved with: spring/summer 2021 it’s 9th home at Spring Village framing floors and walls, hang- • Lot 11 targeted market date Estates. The home was listed ing doors and windows, assem- winter 2021/spring 2022 for $950,000 and settled at bling gable ends, reading blue- $960,000. This home featured prints, laying foundations, con- • Scholarship applicants increased Silestone custom counter tops, structing stairs, installing hard- considerably from last year stainless steel appliances, and wood floors, cabinets, crown • More entrepreneurship programs is a universal designed home molding, and various trim work. made specifically to adapt to participating in Market Day Fund- Small groups of students work many different lifestyles from ing this year with the professional trades in extended families, physically masonry, concrete finishing, limited occupants, or aging in- painting, electrical, plumbing, Lot 9 was listed for $950,000 and place. and heating/air conditioning. sold for $ 960,000 in 15 days! The universal design allows for All nine homes sold in the easy entry. Lowered switches neighborhood allowed the prof- and plugs, comfort height coun- its to be returned to the resi- ters, lowered appliances, and dential construction program to extra-wide doorways and stairs, fund the next home. are some of the features that make this home special. A fully The electrical and plumbing finished basement media room, rough was completed on Lot Inside this issue: bedroom, and full bath are 10. -

Fissures in Standards Formulation: the Role of Neoconservative and Neoliberal Discourses in Justifying Standards Development in Wisconsin and Minnesota

EDUCATION POLICY ANALYSIS ARCHIVES A peer-reviewed scholarly journal Editor: Sherman Dorn College of Education University of South Florida Volume 15 Number 18 September 10, 2007 ISSN 1068–2341 Fissures in Standards Formulation: The Role of Neoconservative and Neoliberal Discourses in Justifying Standards Development in Wisconsin and Minnesota Samantha Caughlan Michigan State University Richard Beach University of Minnesota Citation: Caughlan, S., & Beach, R. (2007). Fissures in standards formulation: The role of neoconservative and neoliberal discourses in justifying standards development in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 15(18). Retrieved [date] from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v15n18/. Abstract An analysis of English/language arts standards development in Wisconsin and Minnesota in the late 1990s and early 2000s shows a process of compromise between neoliberal and neoconservative factions involved in promoting and writing standards, with the voices of educators conspicuously absent. Interpretive and critical discourse analyses of versions of English/language arts standards at the high school level and of public documents related to standards promotion reveal initial conflicts between neoconservative and neoliberal discourses, which over time were integrated in final standards documents. The content standards finally released for use in guiding curriculum in each state were bland and incoherent documents that reflected neither a deep knowledge of the field nor an acknowledgement of what is likely to engage young learners. The study suggests the need for looking more critically at standards as political documents, and a greater Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Education Policy Analysis Archives, it is distributed for non- commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. -

Oak Hill Herndon PERMIT #86 Attention Postmaster: Time Sensitive Material

PRSRT STD U.S. Postage PAID ❖ Martinsburg, WV Oak Hill Herndon PERMIT #86 Attention Postmaster: Time sensitive material. Requested in home 01-15-09 Alum Returns Singing News, Page 2 Sports, Page 10 ❖ Nate Tao of Herndon High School’s Class of ’07 returns to the school Faith, Page 7 to perform as a member ❖ of Ithacappella, Ithaca College’s male a cappella group. Classifieds, Page 13 Classifieds, ❖ Calendar, Page 11 ❖ Opinion, Page 6 Clearview Word Master News, Page 3 More Ways to Have Fun Entertainment, Page 8 Photo by Mike DiCicco/The Connection Photo www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJanuary 14-20, 2009 ❖ Volume XXIII, Number 2 Read us online at connectionnewspapers.comHerndon Connection ❖ January 14-20, 2009 ❖ 1 Obituary THIS IS “PERCY” A Rex rabbit, neutered male. Percy is the softest rabbit you will Dillard Thomas, 90, Dies ever feel. He likes to illard Thomas, father of neering. He married Aline explore and hop Reston resident Kittie Rosenthal in 1941, and in 1948, around. With some D Thomas, died at the age their only child, Kittie, was born. love and patience of 90 this past October in his Dillard is survived by his wife of he will make a hometown of Houston, TX. Dillard 67 years, Aline Thomas; his wonderful pet. was born in Cleburne, Texas along daughter, Kittie Rothschild of with seven brothers and sisters. Herndon; his granddaughter, Jodi HUMANE SOCIETY When Dillard was 7, his mother Rothschild of Reston; his grand- OF FAIRFAX COUNTY died, and a year later, he lost his son, David Rothschild of Falls Hours: Monday-Friday 10-4 and Saturday 10-3. -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

2019 FCPS Honors Program

RECEPTION AND RECOGNITION CEREMONY Wednesday, June 12, 2019 George Mason University Center for the Arts FCPS HONORS 1 Schedule of Events | Wednesday, June 12, 2019 Reception 6 p.m. Music Gypsy Jazz Combo West Springfield High School Keith Owens, Director Awards Ceremony 7 p.m. Opening Woodson High School Vocal Ensemble Amy Moir, Director Welcome Helen Nixon Assistant Superintendent, Human Resources Recognition of the Foundation for Scott Brabrand Fairfax County Public Schools Division Superintendent Employee Award Introductions Helen Nixon Employee Award Presentations Scott Brabrand and Fairfax County School Board and Leadership Team Members Outstanding Elementary New Teacher Outstanding Secondary New Teacher Outstanding New Principal Outstanding School-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding School-Based Operational Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Operational Employee Student Performance Eric Tysarczyk Vocalist, Woodson High School, Senior Employee Award Presentations Continue Outstanding School-Based Leader Outstanding Nonschool-Based Leader Outstanding Elementary Teacher Outstanding Secondary Teacher Outstanding Principal Closing Remarks Helen Nixon 2 FAIRFAX COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS FCPS HONORS 3 Outstanding New Teacher FCPS Honors Sponsors The Outstanding New Teacher Award recognizes both an elementary and secondary teacher who are within their first three years of teaching and demonstrate outstanding performance and superior instructional skills. Any FCPS employee or community member may nominate -

Florida's A++ Plan: an Expansion and Expression of Neoliberal and Neoconservative Tenets in State Educational Policy

Florida's A++ Plan: An Expansion and Expression of Neoliberal and Neoconservative Tenets in State Educational Policy Author: Matthew Dana Laliberte Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104495 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/4.0). FLORIDA’S A++ PLAN Boston College Lynch School of Education Department of Teacher Education/ Special Education, Curriculum and Instruction Curriculum and Instruction FLORIDA’S A++ PLAN: AN EXPANSION AND EXPRESSION OF NEOLIBERAL AND NEOCONSERVATIVE TENETS IN STATE EDUCATIONAL POLICY Dissertation by MATTHEW D. LALIBERTE submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2015 FLORIDA’S A++ PLAN © Copyright by Matthew Dana Laliberte 2015 2 FLORIDA’S A++ PLAN ABSTRACT FLORIDA’S A++ PLAN: AN EXPANSION AND EXPRESSION OF NEOLIBERAL AND NEOCONSERVATIVE TENETS IN STATE EDUCATIONAL POLICY by Matthew D. Laliberte Doctor of Philosophy Boston College, May 2015 Dissertation Committee Chair: Dr. Curt Dudley-Marling This critical policy analysis, informed by a qualitative content analysis, examines the ideological orientation of Florida’s A++ Plan (2006), and its incumbent impact upon social reproduction in the state. Utilizing a theoretical framework that fuses together critical theory (Horkheimer, 1937; Marcuse, 1964; Marshall, 1997), Bernstein’s (1971, 1977) three message systems of education and dual concepts of classification and frame, and Collins‘ (1979, 2000, 2002) notion of the Credential Society, the study examines the ideological underpinnings of the A++ Plan’s statutory requirements, and their effects on various school constituencies, including students, teachers, and the schools themselves. -

Feeder List SY2016-17

Region 1 Elementary School Feeder By High School Pyramid SY 2016-17 Herndon High School Pyramid Aldrin ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Armstrong ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Clearview ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Dranesville ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Herndon ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Hutchison ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Herndon MS Herndon HS - 100% Langley High School Pyramid Churchill Road ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Colvin Run ES Cooper MS - 69% / Longfellow MS - 31% Langley HS - 69% / McLean HS - 31% Forestville ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Great Falls ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Spring Hill ES Cooper MS - 67% / Longfellow MS - 33% Langley HS - 67% / McLean HS - 33% Cooper MS Langley HS - 100% Madison High School Pyramid Cunningham Park ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 76% / Marshall HS - 24 % Flint Hill ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 100% Louise Archer ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 100% Marshall Road ES Thoreau MS - 63% / Jackson MS - 37% Madison HS - 63% / Oakton HS - 37% Vienna ES Thoreau MS - 97% / Kilmer MS - 3% Madison HS - 97% / Marshall HS - 3% Wolftrap ES Kilmer MS - 100% Marshall HS - 61% / Madison HS - 39% Thoreau MS Madison HS - 89% / Marshall HS - 11% Based on September 30, 2016 residing student counts. 1 Region 1 Elementary School Feeder By High School Pyramid SY 2016-17 Oakton High School Pyramid Crossfield ES Carson MS - 92% / Hughes MS - 7% / Franklin - 1% Oakton HS - 92% / South Lakes HS - 7% / Chantilly - 1% Mosby -

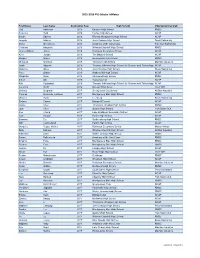

VBODA 2015 FEE Report

4/8/2015 VBODA PARTICIPATION FEES $46,010.00 School Type of School VMEA District Manual Fee Band Manual Fee Orch Amount Paid IDNUMBER Total Paid by Type of School Our Lady of Lourdes 1 unpaid unpaid VBODA577 St. Gertrude High School 1 unpaid unpaid VBODA895 Westminster School 10 unpaid unpaid VBODA847 Mountaintop Montessori 13 unpaid unpaid VBODA521 Tandem Friends School 13 unpaid unpaid VBODA891 Elementary School Total Paid by Type of School $35.00 West Point Elementary Elementary School 1 unpaid unpaid VBODA838 Crossroads Elementary Elementary School 2 unpaid unpaid Highland School Elementary School 9 unpaid unpaid VBODA348 Manassas Park Elementary Elementary School 9 unpaid unpaid VBODA478 Manassas Park Elementary Elementary School 9 unpaid unpaid VBODA479 Manassas Park Elementary Elementary School 9 unpaid unpaid Albert Harris Elementary Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA8 Bedford Hills Elementary Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA45 Blue Ridge Elementary Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA65 Floyd County Elementary Elementary School 6 paid #36519 unpaid $35.00 VBODA224 Hardin Reynolds Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA320 Indian Valley Elementary Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA373 Lincoln Terrance Elem Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA453 1 4/8/2015 VBODA PARTICIPATION FEES $46,010.00 School Type of School VMEA District Manual Fee Band Manual Fee Orch Amount Paid IDNUMBER Linkhorne Elementary Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA455 Meadows of Dan Elementary School 6 unpaid unpaid VBODA503 Patrick -

Trends in Enrollment by High School for Non-Dual Enrolled Students

Trends in Enrollment by High School for Non‐Dual Enrolled Students 1/17/2014 High School Total SU 05 FA 05 SP 06 SU 06 FA 06 SP 07 SU 07 FA 07 SP 08 SU 08 FA 08 SP 09 SU 09 FA 09 SP 10 SU 10 FA 10 SP 11 SU 11 FA 11 SP 12 SU 12 FA 12 SP 13 SU 13 FA 13 Total 98,336 1,832 4,080 3,940 1,913 4,237 3,918 1,892 4,109 3,800 1,946 4,392 4,316 2,284 5,016 4,768 2,394 5,162 4,936 2,547 5,489 5,169 2,492 5,234 4,876 2,455 5,139 Outside VA CEEB Code 28,102 605 1,184 1,197 576 1,231 1,158 555 1,148 1,089 587 1,197 1,264 682 1,412 1,403 707 1,465 1,430 752 1,512 1,456 708 1,394 1,342 686 1,362 James Wood High School 7,297 149 343 325 151 341 306 163 340 314 126 333 298 174 377 346 160 375 338 166 371 350 177 371 352 177 374 Sherando High School 6,975 122 281 265 126 296 279 127 288 251 127 296 276 168 329 303 175 365 349 173 406 377 181 424 376 188 427 Warren County HS 6,233 143 332 279 126 301 290 143 350 282 137 313 316 150 345 312 158 284 281 147 305 284 137 259 231 95 233 Fauquier High School 6,002 90 254 252 139 276 230 106 275 273 143 305 295 153 330 308 136 331 301 154 307 271 132 279 255 140 267 Liberty High School 4,568 62 191 168 76 217 170 60 197 178 66 239 228 87 281 255 115 264 245 133 246 234 90 232 193 110 231 John Handley High School 4,255 77 177 153 76 179 170 83 161 173 84 198 183 94 231 212 99 241 225 108 252 238 100 232 204 90 215 Central High School 3,620 73 170 170 73 163 160 70 168 154 66 189 175 89 189 185 80 187 172 83 183 151 76 168 169 83 174 Millbrook High School 3,592 16 88 80 31 116 102 45 143 120 56 171 147 71 190 171 84 -

Nominations Before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Second Session, 109Th Congress

S. HRG. 109–928 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF HON. PRESTON M. GEREN; HON. MICHAEL L. DOMINGUEZ; JAMES I. FINLEY; THOMAS P. D’AGOSTINO; CHARLES E. McQUEARY; ANITA K. BLAIR; BENEDICT S. COHEN; FRANK R. JIMENEZ; DAVID H. LAUFMAN; SUE C. PAYTON; WILLIAM H. TOBEY; ROBERT L. WILKIE; LT. GEN. JAMES T. CONWAY, USMC; GEN BANTZ J. CRADDOCK, USA; VADM JAMES G. STAVRIDIS, USN; NELSON M. FORD; RONALD J. JAMES; SCOTT W. STUCKY; MARGARET A. RYAN; AND ROBERT M. GATES FEBRUARY 15; JULY 18, 27; SEPTEMBER 19; DECEMBER 4, 5, 2006 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:22 Jun 28, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 36311.TXT SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:22 Jun 28, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 36311.TXT SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 S. HRG. 109–928 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF HON. PRESTON M. GEREN; HON. MICHAEL L. DOMINGUEZ; JAMES I. FINLEY; THOMAS P. D’AGOSTINO; CHARLES E. McQUEARY; ANITA K. BLAIR; BENEDICT S. COHEN; FRANK R. JIMENEZ; DAVID H. LAUFMAN; SUE C. PAYTON; WILLIAM H. TOBEY; ROBERT L. WILKIE; LT. GEN. -

Herndon Class of 2019 Walk Toward the Entrance to George Mason University Eaglebank Arena for Their June 12 Commencement Ceremony

Page, 4 Members of the Herndon Class of 2019 walk toward the entrance to George Mason University EagleBank Arena for their June 12 Commencement ceremony. Hornets on Way to Success News, Page 3 Classifieds, Page 6 Classifieds, v Entertainment, Page 8 v Opinion, Page 5 Two-Mile Makeover News, Page 2 6-20-19 home in Requested Time sensitive material. material. sensitive Time Attention Postmaster: Postmaster: Attention ECR WSS ECR Hunter Mill Democrats Customer Postal permit #322 permit Easton, MD Easton, PAID Hold ‘Unity Party’ Postage U.S. News, Page 6 STD PRSRT Photo by Mercia Hobson/The Connection by Mercia Hobson/The Photo June 19-25, 2019 online at www.connectionnewspapers.com News From left, Dranesville Dis- trict Park Authority Board Member Tim Hackman, Park Authority Executive Director Kirk Kincannon; Dranesville Supervisor John Foust; Ken Neuman, Kingstream HOA; Tyrone Yee, Kingstream of Morgan Gr courtesy Photo HOA; Park Authority Project Manager Eduardo Deleon; and Park Authority Area Manager Wayne Brissey celebrate the completion of the Sugarland Run Stream Valley Park Trail Improve- ments. Photo by Mercia Hobson/The Connection ant A Two-Mile Makeover Volunteers stuff the bus with donations from shoppers. Sugarland Run Stream Valley Park project completed. Stuffing the Bus By Mercia Hobson Authority Board, Park Authority staff and commu- The Connection nity members for a ribbon cutting to celebrate the completion of the project. for Cornerstones airfax County Park Authority (FCPA) con- Trails are the most popular amenity in the Fairfax cluded its $400,000 renovation of the ex- County Park system, according to Judith Pedersen, Giant Food Cornerstones’ Community Fisting trail in Sugarland Run Stream Valley Public Information Officer Fairfax County Park Au- Resource Coordinator Morgan Park in Herndon by contractor, Tibbs Pav- thority. -

PVS Scholar Athletes

2015-2016 PVS Scholar Athletes First Name Last Name Graduation Year High School USA Swimming Club Gail Anderson 2016 Einstein High School RMSC Rebecca Byrd 2016 Fairfax High School NCAP Bouke Edskes 2016 Richard Montgomery High School NCAP Joaquin Gabriel 2016 John Champe High School Snow Swimming Grace Goetcheus 2016 Academy of the Holy Cross Tollefson Swimming Christian Haryanto 2016 Winston Churchill High School RMSC James William Jones 2016 Robinson Secondary School NCAP Kylie Jordan 2016 The Madeira School NCAP Morgan Mayer 2016 Georgetown Day School RMSC Michaela Morrison 2016 Yorktown High School Machine Aquatics Justin Nguyen 2016 Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology NCAP Madeline Oliver 2016 John Champe High School Snow Swimming Peter Orban 2016 Watkins Mill High School NCAP Margarita Ryan 2016 Sherwood High School RMSC Simon Shi 2016 Tuscarora HS NCAP Keti Vutipawat 2016 Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology NCAP Veronica Wolff 2016 McLean High Scool The FISH Zachary Bergman 2017 Georgetown Day School All Star Aquatics Thomas Brown de Colstoun 2017 Montgomery Blair High School RMSC Michael Burris 2017 Leesburg Snow Swimming Sydney Catron 2017 Bishop O'Connell NCAP Daniel Chen 2017 Thomas S. Wootton High School RMSC Jade Chen 2017 Oakton High School York Swim Club Alex Chung 2017 Lake Braddock Secondary School NCAP Cole Cooper 2017 Patriot High School NCAP Brandon Cu 2017 Gaithersburg High School RMSC Will Cumberland 2017 Patriot High School NCAP Margaret Deppe-Walker 2017 Robinson Secondary