Political Management of Ethnic Perceptions African National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa

Safrica Page 1 of 42 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map May 1995 Vol. 7, No.3 SOUTH AFRICA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Continuing Violence in KwaZulu-Natal INTRODUCTION For the last decade South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal region has been troubled by political violence. This conflict escalated during the four years of negotiations for a transition to democratic rule, and reached the status of a virtual civil war in the last months before the national elections of April 1994, significantly disrupting the election process. Although the first year of democratic government in South Africa has led to a decrease in the monthly death toll, the figures remain high enough to threaten the process of national reconstruction. In particular, violence may prevent the establishment of democratic local government structures in KwaZulu-Natal following further elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1995. The basis of this violence remains the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC), now the leading party in the Government of National Unity, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the majority party within the new region of KwaZulu-Natal that replaced the former white province of Natal and the black homeland of KwaZulu. Although the IFP abandoned a boycott of the negotiations process and election campaign in order to participate in the April 1994 poll, following last minute concessions to its position, neither this decision nor the election itself finally resolved the points at issue. While the ANC has argued during the year since the election that the final constitutional arrangements for South Africa should include a relatively centralized government and the introduction of elected government structures at all levels, the IFP has maintained instead that South Africa's regions should form a federal system, and that the colonial tribal government structures should remain in place in the former homelands. -

Pressure on Model School to Shape Up

PRESSURE ON MODEL SCHOOL TO SHAPE-UP By Tselane Moiloa KROONSTAD – The Free State provincial government’s education theme during the weeklong celebrations to mark former president Nelson Mandela’s birthday on Wednesday, July 18, has resonated with learners at Bodibeng Secondary School who have been asked to change the path the school has taken in recent years. Located between the dusty townships of Marabastad and Seeisoville, Bodibeng was counted among the best schools in Free State and South Africa during the apartheid regime and the early 90s, after producing luminaries like the late Adelaide Tambo and former Minister of Communications Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri, Mosuioa “Terror” Lekota, MEC Butana Khompela and his soccer-coach brother Steve Khompela. The school, which was founded in 1928 under the name Bantu High, was the only school for black people during the apartheid regime which offered a joint matriculation board qualification instead of the Bantu education senior certificate, putting it on par with the regime’s best schools of the time. Until 1982, it was the only high school in Kroonstad. But the famed reputation took a knock, despite an abundance of resources. “There is obviously a lot of pressure on us to continue with the legacy and it only makes sense that we come through with our promise to do so,” Principal Itumeleng Bekeer said. Unlike many schools which complain about things like unsatisfactory teacher-learner ratios, Bekeer said this is not a concern because the 24 classes from grade eight to 12 have an average 1:24 teacher-learner ratio. However, the socio-economic circumstances in the surrounding townships impact negatively on learners, with a lot coming to school on empty stomachs. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Church As a Peace Broker: the Case of the Natal Church Leaders' Group and Political Violence in Kwazulu-Natal (1990-1994)1

The Church as a peace broker: the case of the Natal Church Leaders’ Group and political violence in KwaZulu-Natal (1990-1994)1 Michael Mbona 2 School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Moves by the state to reform the political landscape in South Africa at the beginning of 1990 led to increased tension between the Inkatha Freedom Party and the African National Congress in the province of Natal and the KwaZulu homeland. Earlier efforts by the Natal Church Leaders’ Group to end hostilities through mediation had yielded minimal results. Hopes of holding the first general democratic election in April 1994 were almost dashed due to Inkatha’s standoff position until the eleventh hour. This article traces the role played by church leaders in seeking to end the bloody clashes taking place at that time by engaging with the state and the rival political parties between 1990 and 1994. Despite the adoption of new strategies, challenges such as internal divisions, blunders at mediation, and the fact that the church leaders were also “political sympathisers”, hampered progress in achieving peace. While paying tribute to the contribution of other team players, this article argues that an ecumenical initiative was responsible for ending the politically motivated brutal killings in KwaZulu-Natal in the early years of 1990. Introduction The announcement in 1990 by State President FW de Klerk about the release of political prisoners, including Nelson Mandela, and the unbanning of all political parties was a crucial milestone on the journey towards reforming the South African political landscape.3 While these reforms were acclaimed by progressive thinkers within and outside South Africa, tension between 1 This article follows on, as part two, from a previous article by the same author. -

Address by Free State Premier Ace Magashule on the Occasion of the Department of the Premier’S 2014/2015 Budget Vote Speech in the Free State Legislature

ADDRESS BY FREE STATE PREMIER ACE MAGASHULE ON THE OCCASION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE PREMIER’S 2014/2015 BUDGET VOTE SPEECH IN THE FREE STATE LEGISLATURE 08 JULY 2014 Madam Speaker Members of the Executive Council Members of the Legislature Director General and Senior Managers Ladies and Gentlemen Madam Speaker I am delighted to present the first budget vote for the second phase of the transition taking place at the time when South Africans are celebrating 20 years of democracy. Indeed we are celebrating the remarkable gains we made in a relatively short space of time. In our celebration we cannot forget the brave and noble steps taken by heroes like our former President Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. With July being his birthday month, we pay homage to this giant that fearlessly, fiercely and selflessly fought for South Africans to live in a democratic and open society. It is only befitting that we continue to honour him posthumously by continuing with his legacy of helping people in need and fighting injustice. In the coming days, we will go to various towns and rural areas to launch projects for the upliftment of the needy people. Our programmes will exceed the 67 minutes to enable us to leave indelible and profound memories of tangible change in their lives. In line with President Jacob Zuma’s pronouncement during the 1 State of the Nation Address, we will embark on a massive clean-up campaign in our towns, schools and other areas. Today’s budget speech marks the beginning of a period for radical economic and social transformation. -

Who Is Governing the ''New'' South Africa?

Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa? Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard To cite this version: Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard. Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa?: Elites, Networks and Governing Styles (1985-2003). IFAS Working Paper Series / Les Cahiers de l’ IFAS, 2006, 8, p. 13-37. hal-00799193 HAL Id: hal-00799193 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00799193 Submitted on 11 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ten Years of Democratic South Africa transition Accomplished? by Aurelia WA KABWE-SEGATTI, Nicolas PEJOUT and Philippe GUILLAUME Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS / IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. Under the supervision of appointed editors, each issue covers a specifi c theme; papers originate from researchers, experts or post-graduate students from France, Europe or Southern Africa with an interest in the region. The views and opinions expressed here remain the sole responsibility of the authors. Any query regarding this publication should be directed to the chief editor. Chief editor: Aurelia WA KABWE – SEGATTI, IFAS-Research director. -

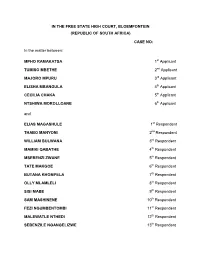

Founding Affidavit Free State High Court-20048.Pdf

IN THE FREE STATE HIGH COURT, BLOEMFONTEIN (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA) CASE NO: In the matter between: MPHO RAMAKATSA 1st Applicant TUMISO MBETHE 2nd Applicant MAJORO MPURU 3rd Applicant ELISHA MBANGULA 4th Applicant CECILIA CHAKA 5th Applicant NTSHIWA MOROLLOANE 6th Applicant and ELIAS MAGASHULE 1st Respondent THABO MANYONI 2nd Respondent WILLIAM BULWANA 3rd Respondent MAMIKI QABATHE 4th Respondent MSEBENZI ZWANE 5th Respondent TATE MAKGOE 6th Respondent BUTANA KHOMPELA 7th Respondent OLLY MLAMLELI 8th Respondent SISI MABE 9th Respondent SAM MASHINENE 10th Respondent FEZI NGUMBENTOMBI 11th Respondent MALEWATLE NTHEDI 12th Respondent SEBENZILE NGANGELIZWE 13th Respondent 2 MANANA TLAKE 14th Respondent SISI NTOMBELA 15th Respondent MANANA SECHOARA 16th Respondent SARAH MOLELEKI 17th Respondent MADALA NTOMBELA 18th Respondent JACK MATUTLE 19th Respondent MEGGIE SOTYU 20th Respondent MATHABO LEETO 21st Respondent JONAS RAMOGOASE 22nd Respondent GERMAN RAMATHEBANE 23rd Respondent MAX MOSHODI 24th Respondent MADIRO MOGOPODI 25th Respondent AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 26th Respondent APPLICANTS’ FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I, the undersigned, MPHO RAMAKATSA do hereby make oath and state that: 3 1. I am an adult male member of the Joyce boom (Ward 25) branch of the ANC in the Motheo region of the Free State province, residing at 28 Akkoorde Crescent, Pellissier, Bloemfontein. I am a citizen of the Republic of South Africa with ID No 6805085412084. I am also a member of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (“MKMVA”) and a former combatant who underwent military training under the auspices of the ANC in order to fight for the implementation of democracy and a bill of rights in South Africa. I have been a member of the ANC for the past 25 years. -

EB145 Opt.Pdf

E EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTHERN AFRICA 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 FAX: (212) 979-1013 S A #145 21 february 1994 _SU_N_D_AY-.::..:20--:FEB:.=:..:;R..:..:U..:..:AR:..:.Y:.....:..:.1994::...::.-_---.". ----'-__THE OBSERVER_ Ten weeks before South Africa's elections, a race war looks increasingly likely, reports Phillip van Niekerk in Johannesburg TOKYO SEXWALE, the Afri In S'tanderton, in the Eastern candidate for the premiership of At the meeting in the Pretoria Many leading Inkatha mem can National Congress candidate Transvaal, the white town coun Natal. There is little doubt that showgrounds three weeks ago, bers have publicly and privately for the office of premier in the cillast Wednesday declared itself Natal will fall to the ANC on 27 when General Constand Viljoen, expressed their dissatisfaction at Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Veree part of an independent Boer April, which explains Buthelezi's head ofthe Afrikaner Volksfront, Inkatha's refusal to participate in niging province, returned shaken state, almost provoking a racial determination to wriggle out of was shouted down while advo the election, and could break from a tour of the civil war in conflagration which, for all the having to fight the dection.~ cating the route to a volkstaat not away. Angola last Thursday. 'I have violence of recent years, the At the very least, last week's very different to that announced But the real prize in Natal is seen the furure according to the country not yet experienced. concessions removed any trace of by Mandela last week, the im Goodwill Zwelithini, the Zulu right wing,' he said, vividly de The council's declaration pro a legitimate gripe against the new pression was created that the king and Buthelezi's nephew. -

Zuma Jailed After Landmark Ruling

InternationalFriday FRIDAY, JULY 9, 2021 Mary Akrami, fighting to keep Afghan women’s Dubai authorities probe port explosion that shook the city Page 11 shelters open Page 18 ESTCOURT, KWAZULU-NATAL: Officials are seen at the Estcourt Correctional Centre, where former South African president Jacob Zuma began serving his 15-month sentence for contempt of the Constitutional Court, in Estcourt, yesterday. — AFP Zuma jailed after landmark ruling South Africa’s first post-apartheid president to be jailed JOHANNESBURG: Jacob Zuma yesterday began a 15-month legal strategy has been one of obfuscation and delay, ultimately weekend that he was prepared to go prison, even though “sending sentence for contempt of court, becoming South Africa’s first in an attempt to render our judicial processes unintelligible,” it me to jail during the height of a pandemic, at my age, is the same post-apartheid president to be jailed after a drama that cam- said. “It is tempting to regard Mr Zuma’s arrest as the end of the as sentencing me to death.” “I am not scared of going to jail for paigners said ended in a victory for rule of law. road” rather than “merely another phase... in a long and fraught my beliefs,” he said. “I have already spent more than 10 years in Zuma, 79, reported to prison early yesterday after mounting a journey,” the foundation warned. Robben Island, under very difficult and cruel conditions”. last-ditch legal bid and stoking defiance among radical supporters As the Wednesday deadline loomed, police were prepared to who had rallied at his rural home. -

King Goodwill Zwelithini's Imbizo

DEVELOPMENT COMMUNICATION ACTIVITY NAME Fight Against Attacks Foreign Nationals; King Goodwill Zwelithini WIMS REFERENCE NUMBER DATE OF THE EVENT 2015/04/20 VENUE & AREA Moses Mabhida Stadium ; eThekwini DC ACTIVITY SYNOPSIS: King Goodwill Zwelithini convened a Fight Against Attacks on Foreign Nationals Imbizo at the Moses Mabhida Stadium in Durban on 20 April 2015. His Majesty spoke out against the recent spates of violent attacks directed at foreign nationals. He strongly condemned the violence saying peace should prevail in South Africa. The King called on traditional leaders to protect foreign nationals and ensure a peaceful reintegration into the community after thousands were displaced. KwaZulu-Natal Premier Senzo Mchunu, MEC for Economic Development Mike Mabuyakhulu, Cllr James Nxumalo and Ministers for Home Affairs Malusi Gigaba and State Security David Mahlobo were in attendance. Religious leaders led the Imbizo in prayer. PHOTO TESTIMONIALS WITH CAPTIONS: ABOVE: His Majesty King Goodwill Zwelithini flanked by Ministers; for State Security David Mahlobo, Home Affairs Malusi Gigaba and KwaZulu-Natal Premier Senzo Mchunu with eThekwini Metro Mayor Cllr James Nxumalo, Inkosi Phathisizwe Chiliza and MEC Economic Development and Tourism, Mike Mabuyakhulu at anti-xenophobia Imbizo. BELOW: King Goodwill Zwelithini called for peace and for foreign nationals to be protected. FAR LEFT: Home Affairs Minister Malusi Gigaba, Premier Senzo Mchunu with King Goodwill Zwelithini. The King called for peace and for foreign nationals to be protected. Above and right left: Several media houses were in attendance as well as religious who prayed for peace and unity at the Imbizo at Moses Mabhida. Thousands of people flocking into the Moses Mabhida Stadium on 12 April to listen to the King deliver his speech. -

Submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture

ACE MAGASHULE OUTA’S SUBMISSION TO THE JUDICIAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO STATE CAPTURE 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................... 0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 PERSONS INVOLVED AND/OR INVITED ......................................................................... 2 THE DEFINITION OF STATE CAPTURE ........................................................................... 3 TIMELINE OF EVENTS ......................................................................................................... 4 12 NOVEMBER 2012 ......................................................................................................... 4 4 MARCH 2013.................................................................................................................... 5 6 MARCH 2013.................................................................................................................... 6 13 MARCH 2013 ................................................................................................................. 6 20 MARCH 2013 ................................................................................................................. 7 23 JULY 2014 ...................................................................................................................... 8 10 NOVEMBER 2014 ........................................................................................................ -

And Minorities in Post-Apartheid South Africa: a Case Study of Indian South Africans

‘Positive Discrimination’ and Minorities in Post-apartheid South Africa: A Case Study of Indian South Africans Anand Singh Abstract There are numerous ways in which people attempt to make sense of the transformation that is taking place in contemporary South Africa, especially with respect to ‘positive discrimination’ and ‘affirmative action’ – often used interchangeably as synonyms1. Against the background of its racialised past, characterised by the highest privileges for Whites and a narrowing of privileges for Coloureds, Indians and Africans (in this order) – during apartheid, reference to changes is often made in the context of a continuation in discriminatory policies that resembles institutionalised patterns of ‘reverse discrimination’, a somewhat grim reminder of the Apartheid era. As people (Indian respondents) refer to this they often bring up a sense of turgidity in at least 3 issues such as ‘positive discrimination’, ‘affirmative action’, and ‘Black Economic Empowerment’. In a similar vein, their references to these being forms of xenophobia, ethnocentrism, ethnic nepotism, collective narcissism, or sheer racism in reverse, shows the lack of clarity that the lay person often has about the academic contexts of these concepts. This article argues that while they may not be accurate, as people often tend to use them interchangeably, the terms often overlap in definitions and they do have one thing in common i.e. reference to institutionalised forms of discrimination and polarisation. While South African Indians often feel that the alienation brought about by affirmative action/positive discrimination is harsh and reverse racism, the evidence herein suggests that ethnic nepotism is a more 1 For the purposes of this article both words will be taken as synonyms.