Knocking the Hustle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

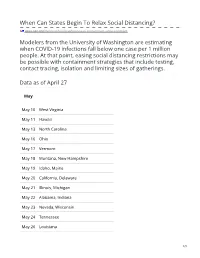

When Can States Begin to Relax Social Distancing?

When Can States Begin To Relax Social Distancing? apps.npr.org/dailygraphics/graphics/states-containment-table-20200420 Modelers from the University of Washington are estimating when COVID-19 infections fall below one case per 1 million people. At that point, easing social distancing restrictions may be possible with containment strategies that include testing, contact tracing, isolation and limiting sizes of gatherings. Data as of April 27 May May 10 West Virginia May 11 Hawaii May 13 North Carolina May 16 Ohio May 17 Vermont May 18 Montana, New Hampshire May 19 Idaho, Maine May 20 California, Delaware May 21 Illinois, Michigan May 22 Alabama, Indiana May 23 Nevada, Wisconsin May 24 Tennessee May 26 Louisiana 1/3 May May 27 District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia May 28 New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania May 30 Washington May 31 Oregon, Wyoming June June 1 Colorado, Mississippi June 3 New Mexico June 7 Minnesota June 13 South Carolina June 15 Texas June 17 Connecticut, Missouri June 21 Florida, Massachusetts, Rhode Island June 22 Kentucky June 28 Arkansas, Georgia June 29 Kansas July July 1 Iowa July 2 South Dakota July 6 Arizona July 7 Utah 2/3 July July 8 Nebraska July 20 North Dakota Notes Projections for Alaska and Oklahoma are unavailable in the latest data update. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington Credit: Stephanie Adeline/NPR 3/3 When Is It Safe To Ease Social Distancing? Here's What One Model Says For Each State npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/04/25/844088634/when-is-it-safe-to-ease-social-distancing-heres-what- one-model-says-for-each-sta April 25, 20207:01 AM ET Nurith Aizenman South Carolina has permitted retail stores to reopen to customers. -

The-Happy-Hustle.Pdf

The Happy Hustle The Happy Hustle Transform the Way You Work Julie Ball Copyright © 2017 Sparkle Hustle Grow. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Cover Design: Carmen Vermillion, VermillionCreativeAgency.com Interior Design: Alexa Bigwarfe of Write.Publish.Sell www.writepublishsell.co Editing: Taylor Roatch Published by Kat Biggie Press. ISBN: 978-0-9994377-0-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017955339 First Edition: September 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Dedication vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Collaboration Over Competition 7 Chapter 2: Do What You Love & Love What You Do 17 Chapter 3: Thriving in Community 27 Chapter 4: Practicing Gratitude 37 Chapter 5: Making Others Happy Through Amazing Customer Service 45 Chapter 6: Give Yourself A Break 55 Chapter 7: It’s Okay to Say No 63 Chapter 8: Make a Difference 71 Chapter 9: Self-Care 77 In Closing 85 Acknowledgements 87 About the Author 91 Dedication To my family, for always being my biggest fans! Introduction My Story 'm Julie Ball, Founder of Sparkle Hustle Grow, a monthly subscription box for female entrepre- neurs.I I launched my first business in 2011 and quick- ly recognized that working for myself was my happy place. One of my biggest inspirations is the female entrepreneur community. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Department Regulation No

Department Regulation No. C-02-009 Offender Mail and Publications Revised 02 July 2019 REJECTION LIST Publications: A Witches Bible – The Complete Witches Handbook Airbrush Action – September/October 2010, March/April 2016 Airbrush Bible AL-HAGG Newsletter Volume 10 Issue 3 Al-Haq Allure - May 2008, December 2011, March 2017 Alternative Revolution – Issue #14 American Art Collector – June 2014 Issue #104, July 2014, #108 October 2014, #109 November 2014, February 2015 American Artist - Spring 2009, May 2010, November 2011, October 2012 American Curves – June 2006, July 2006, November 2006, January 2007, Eye Candy for Men – February 2007, May 2007, Duos Spring 2007, #34 – June 2007, Eye Candy – August 2007 – To Be Displayed Until October 16, 2007, October 2007, Presents Lingerie Magazine – November 2007– December 2007, February 2008, Eye Candy for Men – March 2008, May 2008, June 2008, July 2008, December 2008, Eye Candy for Men - January 2009, February 2009, Eye Candy for Men - May 2009, April 2010, Summer 2012, American Photo - September 2008, November/December 2008, January/February 2009, March/April 2009, May/June 2009, September 2009, May/June 2011 Amerikkkan Prisons on Trial – Guilty! – Number 11-1996 An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons & True Stories – Volume #2 Angel Song – A glorious collection of heavenly bodies by SQP (Volume #1) Anti-Racist Action – Volume 25 #2 April/June 2012 Art in America - September 2008, October 2008, May 2010, March 2016, June/July 2016 Artists Magazine - October 2009, September 2012, November -

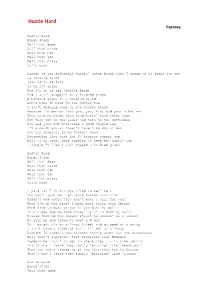

Papoose Hustle Hard

Hustle Hard Papoose Hustle Hard Money Stack Sell that dope Sell that crack Sell that pat Sell that gat Sell that pussy Holla back Listen if you eightball shavin' onthe block turn 7 grams to 14 grams you got ta (Hustle Hard) Turn 14 to 28 fast 56 to 100 grams Now I'm on yo ass (Hustle Hard) And I ain't stoppin' at a hundred grams A hundred grams to a hundred grand Let's take it back to the gutter fam I ain't shaking none of you suckas hands Because I'm better than you, you, him, and your other man They need no brown when they makin' them sucka jams But they get on the radio and turn to the gutterman You and your R&B boss make a good couple fam I'm a catch you at lover's lane like Son of Sam Got the revolver in my fuckin' hand Automatics like that hot 97 concert summer jam Half of my work, make samples to keep em' comin' fam I sample 50 like I just copped a hundred grams Hustle Hard Money Stack Sell that dope Sell that crack Sell that pat Sell that gat Sell that pussy Holla back I paid for 7 this nigga tried to sell me 6 You can't jerk me I got more scales than fish Nigga's mad cause they can't make a sell for shit When I'm on the block I make more sales than Sprint Gone have to bust yo gun if you bust my ballz This nigga owe me some money tryin' to duck my callz Follow them up the oneway street he smokin' on a loosay He seen me and tried to bust a U-way So I caught him on a 2-way Street and gripped on a oozay I ain't have a sidekick but I hit em' on a 2-way Brought 10 nigga's who thought they'd never see you breathless Well that's somethin' -

IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) in Re

Case 21-30209-KRH Doc 349 Filed 03/26/21 Entered 03/26/21 21:03:19 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 172 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) ALPHA MEDIA HOLDINGS LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 21-30209 (KRH) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Julian A. Del Toro, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned cases. On March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296) Furthermore, on March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296 – Notice Only) Dated: March 26, 2021 /s/Julian A. Del Toro Julian A. Del Toro STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-395-0761 Email: [email protected] 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Alpha Media Holdings LLC (3634), Alpha Media USA LLC (9105), Alpha 3E Corporation (0912), Alpha Media LLC (5950), Alpha 3E Holding Corporation (9792), Alpha Media Licensee LLC (0894), Alpha Media Communications Inc. -

Washington Rush Manual

BASEBALL THE RUSH WAY Washington Rush Baseball “Team Manual” Developed, Written & Designed by Red Alert Baseball, LLC About the Developer This Team Manual was the creation of Rob Bowen, Owner and Founder of Red Alert Baseball. Copyright © 2013 Red Alert Baseball, LLC. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials on these pages are copyrighted by Red Alert Baseball, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of these pages, either text or image may be used for any purpose other than personal use. Therefore, reproduction, modification, storage in a retrieval system or retransmission, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, for reasons other than personal use, is strictly prohibited without prior written permission. For any questions or inquiries about this Manual, please contact Rob Bowen via email at [email protected]. Make sure to visit RedAlertBaseball.com for other great services Red Alert Baseball has to offer. You can also follow Red Alert Baseball on our Social Media pages. We provide free info, articles, and drills so you can improve your game. On Twitter: @RedAlertCrew On Facebook: www.Facebook.com/RedAlertBaseball On You Tube: Rob Bowen, Red Alert Baseball Washington Rush Team Manual Developed & Designed by Red Alert Baseball About the Developer Rob Bowen is a former Switch-Hitting Major League Catcher that played for the Minnesota Twins, San Diego Padres, Chicago Cubs, and the Oakland Athletics. He spent 10 years in professional baseball, including 5 seasons of those in the Major Leagues. Rob broke into the big leagues at the young age of 22 and also had the opportunity to play with the Minnesota Twins and the San Diego Padres in the post season. -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t -

Study Guide for the 26Th Annual SU Ag Center and College of Agricultural, Family and Consumer Sciences Collegiate Black History Quiz Bowl February 20, 2020 T

Study Guide for the 26th Annual SU Ag Center and College of Agricultural, Family and Consumer Sciences Collegiate Black History Quiz Bowl February 20, 2020 T. T. Allain Building, 3rd Floor Prepared by Dr. Owusu Bandele Note: These are mostly last year’s questions and answers. They will be reworded this year. There are a few additional questions at the end for you to answer on your own. College 1 1. What was the title of Ralph Ellison’s classic novel? “Invisible Man” 2. ***Who founded the River Road African American Museum and in what city in Louisiana is it located? Kathe Hambrick, Donaldsonville 3. **Who is the only African American lady in the U.S. Senate and what other African American lady served as U.S. Senator? Kamala Harris, Carol Moseley Braun 4. On what date in 1965 was Malcolm X assassinated? February 21 5. Why are schools closed in Berkeley, California on May 19? Birthday of Malcolm X 6. ****Who delivered the eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X and how did he describe Malcolm X in that eulogy? Ossie Davis, our Black shining prince 7. Ossie Davis and his wife Ruby Dee had roles in what Spike Lee Movie? “Do the Right Thing” 8. What famous Grammy-winning artist received major backlash in 2018 for claiming that slavery was a choice and being a proud supporter of Donald Trump? Kanye West 9. What was the name of the abolitionist newspaper founded by Frederick Douglass? The North Star 10. Why was the true North Star in the sky important to enslaved Africans and African Americans? The star helped runaways to find their way to the north. -

Jim Jones So Harlem

So Harlem Jim Jones Free bail posters, tail lights on the roadster (Ferraris) Live life vulgar, the FBI posters (fuck the feds) The fast cars pack guns no holsters (fully loaded) We act dumb don't approach us (watch yourself) We hit the spot & stand on club sofas (ballin) So get the club owners (where he at) Cause we the boss type knicks game court side Big chain sporty ride G4 the lord of skies (flyin) And courts in session so you all could rise (stand up) Then pay homage to the board that lies So many niggaz on my corner died A marijuana how I mourn you guys (I mourn you) And nevermind that My cash better find that (bring my cash) We do the mask work Kick doors cash search (I know you here me) Now where the paper at, man where the yayo at (it get ugly) You make me wait the gat where your baby layin at (fuck your kid) Cause it's a cold world, (Yup) after world Emblem on the car it's no horn on the Capricorn Everybody talkin bout this byrd gang money & this shit is gettin funny to me eee Jump nigga think you a frog and I'ma hit you with one in your knee We switch up the cars, we switch up the broads Got the bitches sayin oh my darling We fucks with the stars, it's us against y'all Bucks at the bar we oh so Harlem A desperado, (Jones) rich like I struck the lotto (ballin) Trained to fight like Cus D'Amato I paint the night in them custom models (galotti's) Racin in the street duckin potholes (speedin) Who gives a fuck is the motto (fuck em) The new sneakers, blackberry's new beepers (text mail) And no tops on the 2 seaters (no tops) It's