Notice of Intent to Grant Variance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Drinking Water Quality Report Portland’S Water System Established 1895

PORTLAND WATER BUREAU 2019 Drinking Water Quality Report Portland’s Water System Established 1895 Columbia River Water Columbia South Quality Lab More than 11,000 Thousands of Shore Well Field water samples are fire hydrants We collected and tested ll Field Protection Ar Pumps pull groundwater safeguard each year. ea the city. from the aquifers of the Columbia South Shore Kelly Butte Well Field. Underground Reservoir Washington Park Reservoir Willamette River (Under Construction) Downtown Portland Powell Butte Underground More than 2,200 miles of water mains Reservoirs To Washington County lie beneath the city’s streets. Reservoirs and tanks store water for household, fire, and emergency supply needs. From the Commissioner Thank you for your interest in the Portland Water Bureau’s 2019 Drinking Water Quality Report. Portlanders have two reliable and safe sources of drinking water: the Bull Run Watershed and the Columbia South Shore Well Field. Our drinking water is some of the best in the world! Your ratepayer dollars are dedicated to ensuring the delivery system is reliable, and delicious water is available to everyone - now, and for generations to come. Please read on to learn more about how the system works and the many projects underway to further protect your water resources and health. Note: The federal Environmental Protection Agency requires specific wording for much of this Report. For more information, or if you have concerns about water quality or paying your bill, see portlandoregon.gov/water, call 503-823-7770, or contact me at [email protected], 503-823-3008. Amanda Fritz COMMISSIONER-IN-CHARGE From the Director I am proud to share the 2019 Drinking Water Quality Report with you. -

Portland Water Bureau and United States Forest Service Bull Run Watershed Management Unit Annual Report April 2019

Portland Water Bureau and United States Forest Service Bull Run Watershed Management Unit Annual Report April 2019 Bull Run Watershed Semi-Annual Meeting 1 2 CONTENTS A. OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................. 4 B. SECURITY and ACCESS MANAGEMENT ................................................................. 4 Bull Run Security Access Policies and Procedures ...................................................... 4 C. EMERGENCY PLANNING and RESPONSE .............................................................. 5 Life Flight Helicopter Landing Zones ............................. Error! Bookmark not defined. D. TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM ................................................................................... 5 2018 Projects: Road 10 (“10H”; Road 10 Shoulder Repair) ......................................... 5 2019 Projects: Road 10 (“10R”: MP 28.77 - 31.85) ....................................................... 5 E. FIRE PLANNING, PREVENTION, DETECTION, and SUPPRESSION ................... 6 Other Fires - 2017 ............................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Hickman Butte Fire Lookout ........................................................................................ 7 F. WATER MONITORING (Quality and Quantity) ...................................................... 8 G. NATURAL RESOURCES – TERRESTRIAL ............................................................... 9 Invasive Species - Plants ............................................................................................... -

FY 2018-19 Water Bureau Requested Budget

WATER BUREAU FY 2018-19 REQUESTED BUDGET FIVE-YEAR PRELIMINARY FINANCIAL PLAN January 29, 2018 PORTLAND UTILITY BOARD Members: To: Mayor Ted Wheeler Allan Warman, Co-chair Commissioner Nick Fish Commissioner Amanda Fritz Colleen Johnson, Co-chair Commissioner Chloe Eudaly Commissioner Dan Saltzman Meredith Connolly Auditor Mary Hull Caballero Ted Labbe Re: Budget Submissions for the Bureau of Environmental Services and Robert Martineau the Portland Water Bureau Micah Meskel Date: January 24, 2018 Lee Moore Dan Peterson The Portland Utility Board (PUB) serves as a citizen-based advisory board for the Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) and the Portland Water Scott Robinson Bureau (PWB). We submit this initial budget letter in compliance with City practice for budget advisory committees, and in response to our Hilda Stevens specific duties to: Mike Weedall “advise the City Council, on behalf of and for the benefit of the citizens of Portland, on the financial plans, capital improvements, annual budget development and rate setting for the City's water, sewer, stormwater, and watershed services. The Board will advise Ex-officio Members: Council on the establishment of fair and equitable rates, consistent with balancing the goals of customer needs, legal Alice Brawley-Chesworth mandates, existing public policies, such as protecting water quality and improving watershed health, operational requirements, and Ana Brophy the long-term financial stability and viability of the utilities. Van Le (3.123.010)” The PUB held five board meetings and two subcommittee meetings to review the FY 2018-19 proposed operating budgets, major additions and Staff Contact: Melissa Merrell adjustments to the five-year capital improvement plans, and decision (503) 823-1810 [email protected] packages for both bureaus. -

Download PDF File Portland's Customer Guide to Water Quality

PORTLAND WATER BUREAU CUSTOMER GUIDE TO Water Quality and Pressure YOUR GUIDE TO: • The basics of water quality and pressure. • Troubleshooting common water quality and pressure concerns. • Plumbing and water heater maintenance tips. • Lead in home plumbing and how to reduce your exposure. • Water filters, backflow prevention, emergency water storage, and water efficiency tips. 1 Portland’s Water System: Two Sources of Water Table of Contents Portland’s drinking water system delivers water from two high-quality sources— CONTACT US Water System Overview 2-3 the Bull Run Watershed and the Columbia South Shore Well Field— to almost one million people in Portland and surrounding communities. Water Quality: A Shared Responsibility 4 Water Quality Line For information on water quality or pressure, Ways to Maintain Drinking Water Quality 5 The Bull Run Watershed The Columbia South Shore Well Field lead in water testing, or to report a water quality • A protected surface water supply located in the • A protected groundwater supply located Water Quality FAQ 6 or pressure concern, please contact: Mt. Hood National Forest 26 miles from Portland. on the south shore of the Columbia River. Lead in Home Plumbing 7 503-823-7525 • Two reservoirs in the watershed store nearly • The well field provides high-quality drinking [email protected] Discolored Water Issues 8-9 10 billion gallons of drinking water. water from 26 active wells located in three different aquifers. 8:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m., Monday–Friday • The watershed receives 135 inches of snow and Taste and Odor Issues 10-11 Interpretation available rain each year. -

Portland, Oregon WATER RATES Fiscal Year July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022

Portland, Oregon WATER RATES Fiscal Year July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 ORDINANCE No.190424 Authorize the rates and charges for water and water-related services beginning July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 and fix an effective date (Ordinance) The City of Portland ordains: Section 1. The Council finds: (1) Pursuant to section 11-105 of the City Charter, this Council has determined revenues are needed to cover Portland Water Bureau costs, and the Commissioner-in-Charge of the Portland Water Bureau recommends the rates and charges prescribed herein be adopted in order to meet the Portland Water Bureau revenue requirements for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2021. (2) This Ordinance has been approved by the Office of the City Attorney. NOW, THEREFORE, the Council directs: a. That the Commissioner-in-Charge and Auditor are authorized to execute on behalf of the City the following rates and charges for use of water and water-related services during the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2021 and ending June 30, 2022. b. This Ordinance is binding City policy pursuant to Code Section 1.07.020. 1 1. BASE CHARGE (A) A base charge per bill, calculated on the actual number of days in a billing cycle, shall be levied on water and/or sewer services connected directly to the City system. A base charge per meter shall be levied on sewer special submeters. A base charge shall be levied on drainage only accounts. The base charge shall be in addition to the volume or extra strength rates charged for water and sewer as follows: Billed charges are as follows: Quarterly (90 day) billed account is $54.71 prorated for the actual number of days billed at $0.6079 per day. -

The City That Works: Preparing Portland for the Future

The City That Works: Preparing Portland for the Future League of Women Voters of Portland Education Fund September 2019 Contents Section 1. Introduction and Purpose of Report ................................................................................ 1 Section 2. Roles of a City Government ............................................................................................ 2 Section 3. Relationships with Surrounding Governments .............................................................. 3 Section 4. Criteria for Evaluating Governmental Effectiveness ...................................................... 5 Section 5. Types of City Government Structures ............................................................................. 6 Section 6. Brief History of Portland’s Government Structure ......................................................... 9 Table 1. Elective Attempts to Change City Structure ................................................................. 10 Table 2. Population Trends ......................................................................................................... 12 Section 7. Current City Bureau Structure ....................................................................................... 12 Table 3. Bureau Assignments as of July 2019 ............................................................................. 13 Section 8. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Commission Form ................................................... 14 Strengths ..................................................................................................................................... -

MUNICIPAL WATER INFRASTRUCTURE CAPITAL IMROVEMENT PLANNING UNDER UNCERTAINTY: DECISION CHALLENGES Azad MOHAMMADI, Ph.D., P.E

MUNICIPAL WATER INFRASTRUCTURE CAPITAL IMROVEMENT PLANNING UNDER UNCERTAINTY: DECISION CHALLENGES Azad MOHAMMADI, Ph.D., P.E. Joe DVORAK Hossein PARANDVASH, Ph.D. city of portland bureau of water works. portland, oregon usa [email protected] ABSTRACT The City of Portland Bureau of Water Works (PWB) has supplied domestic water to Portland- area residents since 1885. It is the largest supplier in Oregon, and providing both retail and wholesale water to nearly 840,000 people. Portland’s primary source of supply, the Bull Run Reserve, is an unfiltered water source. The PWB faces a wide variety of challenges and uncertainties in the new millennium. These uncertainties arise from several principal sources: current federal regulatory requirements and potential future changes that affect water quality standards; treatment and the Endangered Species Act (ESA); conservation; decisions by current and potential wholesale customers about whether to obtain supply from Portland or elsewhere; decisions about where to obtain supply in the future and whether groundwater will be a basic component of the future supply or will be reserved only for emergencies; supply reliability; regionalization of the Portland’s supply system; demand forecasts; and the impact of climate variability. In an attempt to better understand these uncertainties, and develop a decision framework for an integrated strategy that will guide the timing and cost implications of the PWB’s capital improvement programs (CIP), the PWB has commissioned a number of technical studies over the past 5 years. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the decision process and the factors that have influenced and shaped the integration of the results of the studies, including the recently completed Climate Variability Study. -

Triannual Water Quality Analysis November 2018

Portland Water Bureau Triannual Water Quality Analysis November 2018 The secondary standards apply to substances that may affect water taste, odor, or color; may stain Bull Run Water sinks, bathtubs, or laundry; or may interfere with The Portland Water Bureau supplies water to over treatment processes. 970,000 people in the Portland metropolitan area. The primary water source is the protected Bull Run watershed 26 miles east of Portland. The water from About This Report Bull Run is low in dissolved minerals and meets or This report presents analytical results for Portland's exceeds all drinking water quality standards as water to those needing technical data on water measured at the entry point to the distribution system. quality. The report covers results for treated Bull Run water from December 2017 through November 2018, emphasizing results from November 13, 2018. Water Treatment Analytical results for groundwater from the Chlorine is used as the primary raw water Columbia South Shore Well Field, which was disinfectant. The chlorine concentration entering the operated in a blending mode from March 12 to 21, distribution system is adjusted seasonally to account 2018, and June 20 to October 17, 2018, are included for changes in water quality. Since September 2014, in the April 2018 report. the target chlorine concentration has ranged from 2.2 to 2.5 parts per million (ppm). Once primary Please feel free to provide feedback on the report; disinfection is complete, ammonium hydroxide contact information is provided at the bottom of the (aqueous ammonia) is added to the chlorinated water. report. Additional background information is Ammonia reacts with chlorine to form a long-lasting available in the annual Water Quality Report, chloramine disinfectant residual. -

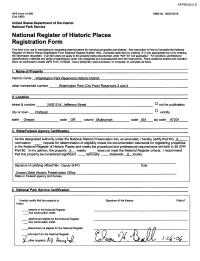

Fo /Vj\ Off , ,, , F » a T Q -X Other (Explain): /V U /Tcce^L *^Wc Uv^V^ /*

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct.1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Washington Park Reservoirs Historic District other names/site number Washington Park (City Park) Reservoirs 3 and 4 2. Location street & number 2403 S.W. Jefferson Street not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally __ statewide X locally. -

2013 Water Quality Report Online

2013quality your water REPORT drinking Water Testing water Tualatin and the Portland Water Bureau monitor for approximately 200 regulated and 2013 unregulated contaminants in drinking water, including pesticides and radioactive contaminants. All monitoring data in this report are from 2013. If a known health-related contaminant is not listed in this report, it was not detected in the drinking water by either agency. Portland Powell Butte Underground Bull Run Storage Watershed Questions? Tualatin If you have questions about this report, please contact Mick Wilson at 503-691-3095. You may also wish to visit the City’s website at www.tualatinoregon.gov or call the Oregon Health Authority/Drinking Water Program at 971- 673-0405 or visit their website at public.health.oregon. gov/healthyenvironments/drinkingwater/pages/ index.aspx City of Tualatin Operations Department Visit the 2013 Water Quality Report online. 18880 SW Martinazzi Avenue Tualatin, OR 97062 printed on recycled paper www.tualatinoregon.gov WATER QUALITY REPORT TUALATIN, OREGON Este informe contiene informacion muy importante sobre su agua beber. Traduzcalo o hable con alguien que lo entienda bien. Based on data from the calendar year 2013 your The Columbia South Shore Well Field provides high-quality drinking water from drinking groundwater production wells located in three different aquifers. In 2013, over the course of 7 days beginning July 20, the Portland Water Bureau supplemented the Bull Run drinking water 2013 supply with approximately 30 million gallons of groundwater as part of an annual groundwater water maintenance operation. If this information looks familiar, it should. Tualatin has been providing similar Portland has a long history of groundwater protection in the Columbia South Shore dating back information to our customers for fourteen years now. -

Portland Water Bureau's 2020 Drinking Water Quality Report

Portland Water Bureau 2020 Drinking Water Quality Report Page | 1 Portland Water Bureau’s 2020 Drinking Water Quality Report Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................... 1 Portland’s Drinking Water Sources ............................................................... 2 Water for People, Water for Fish ................................................................... 4 Facts about Our Drinking Water System ....................................................... 5 Frequently Asked Questions About Water Quality ........................................ 6 What the EPA Says Can Be Found in Drinking Water .................................. 9 Additional Testing Completed in 2019......................................................... 10 Definitions of acronyms used in data tables ................................................ 13 Contaminants Detected in 2019 .................................................................. 16 About These Contaminants ......................................................................... 22 Monitoring for Cryptosporidium ................................................................... 25 Special Notice for Immunocompromised Persons ...................................... 27 Bull Run Treatment Projects – Our water: Safe and abundant for generations to come. ................................................................................... 28 Reducing Exposure to Lead ....................................................................... -

Hydrogeologic Setting and Preliminary Estimates of Hydrologic

Hydrogeologic Setting and Preliminary Estimates of Hydrologic Components for Bull Run Lake and the Bull Run Lake Drainage Basin, Multnomah and Clackamas Counties, Oregon U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4064 Prepared in cooperation with CITY OF PORTLAND BUREAU OF WATER WORKS Cover. Photograph shows Bull Run Lake, viewed southeastward towards Mount Hood. The scene was described by Woodward (Portland Oregonian, August 18, 1918): “ The lake, clear, deep, and cold, ***, nestles like an emerald or turquoise with the changing lights or shadows at the base of these rocky, wooded slopes and above and beyond all, overlooking and reflected in its clear depths, lies snow-capped Mount Hood.” Photograph credit: U.S. Forest Service, circa 1960. Hydrogeologic Setting and Preliminary Estimates of Hydrologic Components for Bull Run Lake and the Bull Run Lake Drainage Basin, Multnomah and Clackamas Counties, Oregon By DANIEL T. SNYDER and DORIE L. BROWNELL U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4064 Prepared in cooperation with CITY OF PORTLAND BUREAU OF WATER WORKS Portland, Oregon 1996 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director The use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Branch of Information