Historical Preservation in Globalizing Shanghai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

The German-American Bund: Fifth Column Or

-41 THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUND: FIFTH COLUMN OR DEUTSCHTUM? THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By James E. Geels, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 Geels, James E., The German-American Bund: Fifth Column or Deutschtum? Master of Arts (History), August, 1975, 183 pp., bibliography, 140 titles. Although the German-American Bund received extensive press coverage during its existence and monographs of American politics in the 1930's refer to the Bund's activities, there has been no thorough examination of the charge that the Bund was a fifth column organization responsible to German authorities. This six-chapter study traces the Bund's history with an emphasis on determining the motivation of Bundists and the nature of the relationship between the Bund and the Third Reich. The conclusions are twofold. First, the Third Reich repeatedly discouraged the Bundists and attempted to dissociate itself from the Bund. Second, the Bund's commitment to Deutschtum through its endeavors to assist the German nation and the Third Reich contributed to American hatred of National Socialism. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION... ....... 1 II. DEUTSCHTUM.. ......... 14 III. ORIGIN AND IMAGE OF THE GERMAN- ... .50 AMERICAN BUND............ IV. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BUND AND THE THIRD REICH....... 82 V. INVESTIGATION OF THE BUND. 121 VI. CONCLUSION.. ......... 161 APPENDIX....... .............. ..... 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY......... ........... -

A Neighbourhood Under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars

European Journal of East Asian Studies EJEAS . () – www.brill.nl/ejea A Neighbourhood under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars Christian Henriot Institut d’Asie orientale, Université de Lyon—Institut Universitaire de France [email protected] Abstract War was a major aspect of Shanghai history in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet, because of the particular political and territorial divisions that segmented the city, war struck only in Chinese-administered areas. In this paper, I examine the fate of the Zhabei district, a booming industrious area that came under fire on three successive occasions. Whereas Zhabei could be construed as a success story—a rag-to-riches, swamp-to-urbanity trajectory—the three instances of military conflict had an increasingly devastating impact, from shaking, to stifling, to finally erase Zhabei from the urban landscape. This area of Shanghai experienced the first large-scale modern warfare in an urban setting. The skirmish established the pattern in which the civilian population came to be exposed to extreme forms of violence, was turned overnight into a refugee population, and lost all its goods and properties to bombing and fires. Keywords war; Shanghai; urban; city; civilian; military War is not the image that first comes to mind about Shanghai. In most accounts or scholarly studies, the city stands for modernity, economic prosperity and cultural novelty. It was China’s main financial centre, commercial hub, indus- trial base and cultural engine. In its modern history, however, Shanghai has experienced several instances of war. One could start with the takeover of the city in by the Small Sword Society and the later attempts by the Taip- ing armies to approach Shanghai. -

Regeneration and Sustainable Development in the Transformation of Shanghai

Ecosystems and Sustainable Development V 235 Regeneration and sustainable development in the transformation of Shanghai Y. Chen Department of Real estate and Housing, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology Abstract Globalisation has had an increasing impact on the transformation of Chinese cities ever since China adopted the open door policy in 1978. Many cities in China have been struggling with the challenges of urban regeneration created by the restructuring of the traditional economy and increasing competition between cities for resources, investment and business. The closure of docks, warehouses and industries, and the deteriorating position of traditional urban centres not only created problems but also created exceptional opportunities to reshape cities and create new functions. But this kind of process also generates a series of physical, economic and social consequences for cities to tackle. In many cases the problems exceed the capacity of the local community to adapt and respond. This paper examines a number of urban regeneration projects in Shanghai, in the hope of providing a better understanding of the process of urban regeneration in China and how best to ensure that such regeneration is sustainable. The paper reassesses the aims of regeneration, the mechanisms involved in the regeneration process and its physical, economic and social consequences, discusses how to achieve sustainable development in urban regeneration and makes recommendations for future action. 1 Introduction Global market forces and increasing globalisation are clearly playing a role in the transformation of cities and towns. In most countries urban systems are experiencing dramatic changes brought about by economic restructuring, continuous mass migration and the arrival of immigrants. -

Heng Feng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China

Heng Feng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/offices-heng-feng-road-zhabei-district- shanghai This fully serviced business centre is in a great location within a premium office building offering spectacular views of the Su Zhou Creek. There's a comprehensive package of services available for clients, including IT support, accounting assistance and business licencing. There are conference rooms available, a telephone answering service and other types of administrative support, all from a highly convenient town centre location offering 24 hour access, security system and plenty of car parking spaces. Transport links Nearest tube: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Nearest railway station: Shanghai Railway Station Nearest road: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Nearest airport: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Administrative support Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High speed internet IT support available Meeting rooms Modern interiors Near to subway / underground station Reception staff Security system Telephone answering service Town centre location Location This business centre is in a great location in the central business district amongst the hub of public transportation choices. It's only 50 metres from Subway Line 1, alongside Huaihai Road and Nanjing Road and Shanghai Railway Station is also easily accessible. Points of interest within 1000 metres Hanzhong -

The Oriental Pearl Radio & TV Tower 东方明珠 Getting in Redeem Your

The Oriental Pearl Radio & TV Tower 东方明珠 Getting In Redeem your pass for an admission ticket at the first ticket office, near No. 1 Gate. Hours Daily, 8:00 am-9:30 pm. Address No. 1 Lujiazui Century Ave Pudong New Area, Shanghai Public Transportation Take Metro Line 2 and get off at Lujiazui Station, get out from Exit 1 and walk to The Oriental Pearl Radio & TV Tower. Yu Garden (Yuyuan) 豫园 Getting In Please redeem your pass for an admission ticket at the Yuyuan Garden ticket office located on the north side of the Huxin Pavilion Jiuqu Bridge prior to entry. Hours Daily, 8:45 am-4:45 pm. Address No. 218 Anren St Huangpu District, Shanghai Public Transportation Take Metro Line 10 and get off at Yuyuan Station, then walk to Yu Garden. Shanghai World Financial Center Observatory 上海环球金融中心 Getting In Please redeem your pass for an admission ticket at the Global Finance Center F1 ticket window located at Lujiazui Century Ave. Hours Daily, 9:00 am-10:30 pm. Address B1 Ticketing Window, World Financial Center 100 Century Avenue Lujiazui, Pudong New Area, Shanghai Public Transportation Take Metro Line 2 and get off at Lujiazui Station, then walk to Shanghai World Financial Center. Shanghai Hop-On Hop-Off Sightseeing Bus Tour 观光巴士 Getting In You must first redeem your pass for a bus ticket at one of the following locations prior to boarding: Nanjing Road Station (New World City Stop): Opposite to New World City, No. 2-88 Nanjing West Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai Bund A Station (Sanyang Food Stop): Beside Sanyang Food, 367 East Zhongshan Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai (near Beijing East Road) Shiliupu Station (Pujiang Tour Terminal Stop): 531 Zhongshan East Second Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai Yuyuan Station (Yongan Road, Renmin Road): Xinkaihe Road, Renmin Road, next to the bus stop in front of the Bund soho. -

Discussion on the Segmentation and Unification of Public Space Within Shanghai Historic Lane Neighbourhood

ICOA543: BETWEEN FAMILY AND STATE: DISCUSSION ON THE SEGMENTATION AND UNIFICATION OF PUBLIC SPACE WITHIN SHANGHAI HISTORIC LANE NEIGHBOURHOOD Subtheme 01: Integrating Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development by engaging diverse Communities for Heritage Management Session 2: Management, Documentation Location: Stein Auditorium, India Habitat Centre Time: December 13, 2017, 14:30 – 14:45 Author: Xiang Zhou, Aya Kubota Xiang Zhou, who achieved his bachelor’s degree in Landscape Architecture at Beijing Forestry University, China, and received his master’s degree in Landscape Architecture at Tongji University, China, is currently conducting his Ph.D. Study on Urban Design at The University of Tokyo under the supervision of Prof. Aya KUBOTA, at the Territorial Design Studies Unit. His research interests are urban regeneration and historic precinct revitalization, urban & rural community sustainable development, territorial cultural landscape and Chinese classic gardens. Abstract: Shanghai’s historic lane neighbourhood is a social combination established on residents’ recognition of cultural identity and rights. It has blended into their daily life, shaping their cultural characters, developing the basic tone of Shanghai urban life, and becoming a mainstream living space in Shanghai. Analyzed under the perspective of daily life, Hongkou River area in Shanghai is selected as a case study to identify sustainable means towards equity. Through empirical research, the thesis believes identification of three distinct worlds: Shikumen lane neighbourhood, new-built commodity house district, cultural and creative industrial district, under the collective name of a unified community, apparently exists within the residents’ cognitive map. Accordingly, urban segmentations between the three worlds reflect on the physical differences in entrance guard, architectural type and interactive mode in their daily lives. -

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese Historical Phonology Differs from Most Domains of Contemporary Linguisti

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese historical phonology differs from most domains of contemporary linguistics in that its general framework is based in large part on a genuinely native tradition. The non-Western outlook of the terminology and concepts used in Chinese historical phonology make this field extremely difficult to understand for both experts in other fields of Chinese linguistics and historical phonologists specializing in other language families. The framework of Chinese phonology derives from the tradition of rhyme books and rhyme tables, which dates back to the medieval period (see section 1 and 2, as well as the corresponding entries). It is generally accepted that these sources were not originally intended as linguistic descriptions of the spoken language; their main purpose was to provide standard character readings for literary Chinese (see subsection 2.4). Nevertheless, these documents also provide a full-fledged terminology describing both syllable structure (initial consonant, rhyme, tone) and several phonological features (places of articulation of consonants and various features that are not always trivial to interpret, see section 2) of the Chinese language of their time (on the problematic concept of “Middle Chinese”, see the corresponding entry). The terminology used in this field is by no means a historical curiosity only relevant to the history of linguistics. It is still widely used in contemporary Chinese phonology, both in works concerning the reconstruction of medieval Chinese and in the description of dialects (see for instance Ma and Zhang 2004). In this framework, the phonological information contained in the medieval documents is used to reconstruct the pronunciation of earlier stages of Chinese, and the abstract categories of the rhyme tables (such as the vexing děng 等 ‘division’ category) receive various phonetic interpretations. -

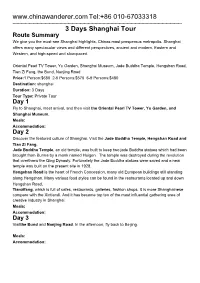

3 Days Shanghai Tour Route Summary We Give You the Must-See Shanghai Highlights, Chinas Most Prosperous Metropolis

www.chinawanderer.com Tel:+86 010-67033318 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 3 Days Shanghai Tour Route Summary We give you the must-see Shanghai highlights, Chinas most prosperous metropolis. Shanghai offers many spectacular views and different perspectives, ancient and modern, Eastern and Western, and high-speed and slow-paced. Oriental Pearl TV Tower, Yu Garden, Shanghai Museum, Jade Buddha Temple, Hengshan Road, Tian Zi Fang, the Bund, Nanjing Road Price:1 Person:$680 2-5 Persons:$570 6-9 Persons:$480 Destination: shanghai Duration: 3 Days Tour Type: Private Tour Day 1 Fly to Shanghai, meet arrival, and then visit the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, Yu Garden, and Shanghai Museum. Meals: Accommodation: Day 2 Discover the featured culture of Shanghai. Visit the Jade Buddha Temple, Hengshan Road and Tian Zi Fang. Jade Buddha Temple, an old temple, was built to keep two jade Buddha statues which had been brought from Burma by a monk named Huigen. The temple was destroyed during the revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty. Fortunately the Jade Buddha statues were saved and a new temple was built on the present site in 1928. Hengshan Road is the heart of French Concession, many old European buildings still standing along Hengshan. Many various food styles can be found in the restaurants located up and down Hengshan Road. Tianzifang, which is full of cafes, restaurants, galleries, fashion shops. It is more Shanghainese compare with the Xintiandi. And it has become top ten of the most influential gathering area of creative industry in Shanghai. Meals: Accommodation: Day 3 Visitthe Bund and Nanjing Road. In the afternoon, fly back to Beijing. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

S Suffixes in Old Chinese?

How many *-s suffixes in Old Chinese? Guillaume Jacques To cite this version: Guillaume Jacques. How many *-s suffixes in Old Chinese? . Bulletin of Chinese linguistics, Brill, 2016, 9 (2), pp.205-217. 10.1163/2405478X-00902014. halshs-01566036 HAL Id: halshs-01566036 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01566036 Submitted on 20 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. How many *-s suffixes in Old Chinese?* Guillaume Jacques July 20, 2017 1 Introduction While qusheng 去聲 derivation is one of the most prominent trace of mor- phology in Old Chinese, it is probably also the least understood one, as it presents diverse and even contradictory functions, to the extent that Downer (1959, 262), in his seminal article, argued that it was simply a way of creat- ing new words, not a derivation with a well-defined grammatical function.1 Yet, we know thanks to the work of scholars such as Haudricourt (1954), Forrest (1960); Schuessler (1985) and Sagart (1999) that qusheng derivation comes (at least in part) from *-s suffixes. As -s suffixes with functions similar to those that have been reconstructed for Old Chinese are attested and even are still productive in more conservative languages of the Trans-Himalayan family, it is worthwhile to explore the exact opposite hypothesis to Downer’s ultrascepticism, namely that the vast array of functions of the *-s is due to the merger of many independent dental suffixes, and constitute indeed obscured traces of a former inflectional system. -

Land Use Dynamics of the Fast-Growing Shanghai Metropolis, China (1979–2008) and Its Implications for Land Use and Urban Planning Policy

Sensors 2011, 11, 1794-1809; doi:10.3390/s110201794 OPEN ACCESS sensors ISSN 1424-8220 www.mdpi.com/journal/sensors Article Land Use Dynamics of the Fast-Growing Shanghai Metropolis, China (1979–2008) and its Implications for Land Use and Urban Planning Policy Hao Zhang, Li-Guo Zhou, Ming-Nan Chen and Wei-Chun Ma * Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Fudan University, 220 Handan road, Shanghai 200433, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (L.G.Z.); [email protected] (M.N.C.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-21-5632. Received: 17 December 2010; in revised form: 17 January 2011 / Accepted: 19 January 2011 / Published: 31 January 2011 Abstract: Through the integrated approach of remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) techniques, four Landsat TM/ETM+ imagery acquired during 1979 and 2008 were used to quantitatively characterize the patterns of land use and land cover change (LULC) and urban sprawl in the fast-growing Shanghai Metropolis, China. Results showed that, the urban/built-up area grew on average by 4,242.06 ha yr−1. Bare land grew by 1,594.66 ha yr−1 on average. In contrast, cropland decreased by 3,286.26 ha yr−1 on average, followed by forest and shrub, water, and tidal land, which decreased by 1,331.33 ha yr−1, 903.43 ha yr−1, and 315.72 ha yr−1 on average, respectively. As a result, during 1979 and 2008 approximately 83.83% of the newly urban/built-up land was converted from cropland (67.35%), forest and shrub (9.12%), water (4.80%), and tidal land (2.19%).