An Audience-Oriented Approach to Hebrews 10: 19― 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?

Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship Volume 8 Article 2 May 2021 Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? Jonathan T. Priddy Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Priddy, Jonathan T. (2021) "Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?," Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 8 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Divinity at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? Cover Page Footnote Priddy, Jonathan T. (2021) “Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?,” Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 7 , Article 4. This article is available in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol8/iss1/2 Priddy: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? 1 Introduction The warning passage of Hebrews 10:26-31 is one of five warning passages throughout the book of Hebrews regarding apostasy. Hebrews 1:1-2:4; 3:7-12; 5:11-6:15; 10:26-31; and 12:25-27 are the five warning passages; the one being addressed in this paper is the fourth, and arguably the most serious and sobering. -

8-02-20 Hebrews 10-26-31 Transcript

FEARFUL EXPECTATIONS Hebrews 10:26–31 • Pastor Luke Herche Please turn with me, if you would, in your Bibles to Hebrews chapter 10, verses 26–31. That'll be our sermon text for this morning, Hebrews 10:26–31. And before we read that together, let's pray together. Our Lord Jesus, we do come, we come to you. We come to you this morning because we need you. We come to you because we are sinful and broken. We come to you because we are weak and weary. And we pray that you would meet with us, that you would meet with us in your word. And, Lord Jesus, we come to a difficult passage of your word this morning, a challenging passage, and so we pray especially that you would meet with us, that you would–even in the midst of this difficulty–that you would remind us of your grace and mercy. Teach us, Jesus, by your Spirit. We pray these things in Jesus’ name, amen. Hebrews chapter 10, beginning with verse 26. For if we go on sinning deliberately after receiving the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a fearful expectation of judgment, and a fury of fire that will consume the adversaries. Anyone who has set aside the law of Moses dies without mercy on the evidence of two or three witnesses. How much worse punishment, do you think, will be deserved by the one who has spurned the Son of God, and has profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified, and has outraged the Spirit of grace? For we know him who said, "Vengeance is mine; I will repay." And again, "The Lord will judge his people." It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God. -

James and His Readers James 1:1

Lesson 1 James and His Readers James 1:1 An Epistle On Christian Living The book of James has most often been placed in a group with 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2 and 3 John and Jude. The seven books, as a group, are often called the general epistles. This title comes from the fact that they all are written to the church in general or a wide section of the church, instead of to a church in a specific city. In many ways, this epistle could be called a commentary on the sermon on the mount. James reveals the very heart of the gospel. He tells Christians how to live daily for the Master. Coffman says, "There is no similar portion of the sacred scriptures so surcharged with the mind of Christ as is the Epistle of James." Shelly titles his book on James What Christian Living Is All About and suggests James 1:27 sounds the theme of the book, which is pure and undefiled religion. James, The Lord's Brother The author identifies himself as James (James 1:1). Four men in the New Testament are called James. One was the father of Judas, not Iscariot (Luke 6:16; Acts 1:13). It seems unlikely that this is our author since we know so little of him. The author of this book was so well known to the early church that he only signed his name. James, the son of Alphaeus, was one of the Lord's apostles (Acts 1:13; Luke 6:15; Mark 3:18; Matthew 10:32). -

“Three to Get Ready” Dr. David Jeremiah

Bringing it Home “Three to Get Ready” Dr. David Jeremiah 1. Dr. Jeremiah said, “Love and good works do not just happen. They need to be September 25, 2011 ‘stimulated.’” How can we, as believers, stimulate love and good works in Hebrews 10:19-25 ourselves as well as in others? What does a stimulation to love and good works look like? Sound like? Small Group Questions I. Let us draw near in faith - Hebrews 10:19-22 A. The call to fellowship with God - Heb. 10:22a; James 4:8; Ps. 73:28 B. The confidence of fellowship with God - Heb. 10:19a; 9:7; 4:16; 7:25 2. Today you are in one of two boats; an anchored boat (in fellowship with God and His people) or an unanchored boat (out of fellowship with God and/or His C. The cost of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:19b people). D. The contrast of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:20a a. If you are in an unanchored boat, what decision do you need to make so that you can climb out of your boat and into one that is anchored? E. The closeness of fellowship with God - Heb. 10:20b; Rom. 8:31-34 What specific storm are you facing? How would facing this storm with God, or His people, change your perspective on the storm? F. The creator of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:21 G. The certainty of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:22a; James 1:6-8 H. The cleansing of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:22b; 9:13-14; b. -

Handfuls on Purpose Sample

HANDFULS ON PURPOSE SAMPLE Contents NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES PAGES Philemon, .. 9 Hebrews, .. 15 James, .. 24 1 Peter, .. 46 2 Peter, . 92 EXPOSITORY STUDIES- The Penitential Psalm—Psalm 51 113 The Golden Passional--Isaiah 53, 133 The Death of Christ, 167 Gospel Studies, 2OO Bible Readings,. 261 Studies for Believers, 281 Handfuls on Purpose New Testament Studies Philemon This is the briefest of all Paul's Epistles. It is the only sample of the Apostle's private correspondence that has been preserved. It is known as "The Courteous Epistle. " Its object was to persuade Philemon not to punish, but reinstate, his runaway slave, called Onesimus, and as he was now converted, treat him as a brother in the Lord. THE TASK AND ITS ACCOMPLISHMENT. PHILEMON. I. The Task. Invariably, in those days, runaway slaves were crucified. Paul must try to conciliate the master-Philemon—without humiliating the servant—Onesimus; to commend the repentant wrong-doer, without extenuating his offence; thus he must balance the claims of justice and mercy. II. Its Solution. 1. Touching Philemon's heart by several times mentioning that he was a prisoner for the Gospel's sake. 2. Frankly and fully recognised Philemon's most excellent Christian character, thus making it difficult for him to refuse to live up to his reputation, and to lead him to deal graciously with the defaulter. 3. Delayed mentioning the name of the penitent until he had paved the way. 4. Referred to Onesimus as his "son," thus establishing the new kinship in Christ. 5. After presenting his request, assumed Philemon would do as he had requested (21) . -

Hebrews 10 Resources

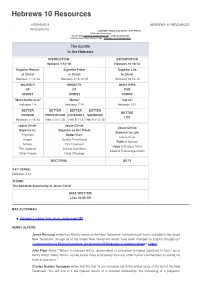

Hebrews 10 Resources HEBREWS 9 HEBREWS 11 RESOURCES RESOURCES CONSIDER JESUS OUR GREAT HIGH PRIEST Click chart to enlarge Charts from Jensen's Survey of the NT - used by permission Another Chart Right Side of Page - Hebrews - Charles Swindoll The Epistle to the Hebrews INSTRUCTION EXHORTATION Hebrews 1-10:18 Hebrews 10:19-13 Superior Person Superior Priest Superior Life of Christ in Christ In Christ Hebrews 1:1-4:13 Hebrews 4:14-10:18 Hebrews 10:19-13 MAJESTY MINISTRY MINISTERS OF OF FOR CHRIST CHRIST CHRIST "Much better than" "Better" "Let us" Hebrews 1:4 Hebrews 7:19 Hebrews 12:1 BETTER BETTER BETTER BETTER BETTER PERSON PRIESTHOOD COVENANT SACRIFICE LIFE Hebrews 1:1-4:13 Heb 4:14-7:28 Heb 8:1-13 Heb 9:1-10:18 Jesus Christ: Jesus Christ: Jesus Christ: Superior to: Superior as Our Priest Superior for Life Prophets Better than: Let us have Angels Earthly Priesthood Faith to Believe Moses Old Covenant Hope to Endure Trials The Sabbath Animal Sacrifices Love to Encourage others Other Priests Daily Offerings DOCTRINE DUTY KEY VERSE: Hebrews 4:14 THEME: The Absolute Superiority of Jesus Christ DATE WRITTEN: circa 64-68 AD MAX ALDERMAN Hebrews: Looking Unto Jesus - enter page 288 HENRY ALFORD James Rosscup writes that Alford's series on the New Testament "contains much that is valuable in the Greek New Testament...though all of the Greek New Testament words have been changed to English throughout." (Commentaries for Biblical Expositors: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works or Logos) John Piper writes ""When I’m stumped with a...grammatical or syntactical or logical [question] in Paul, I go to Henry Alford. -

Jewish Epistles

JEWISH EPISTLES Week 46: The Other Apostles’ Teachings (1) James, 45 Others (Hebrews and James) Jude, 45-70 from This week we will look at the two letters written specifically to the Jewish Christians. Galatians, 49 Chronologically speaking, James was probably first of all the New Testament letters Letters written, even before Paul penned Galatians (45ad-ish). And though we do not know exactly who wrote the letter to the Hebrews (some regard Paul as the author while others 1 Thessalonians, 50 propose Luke, Barnabas, or Apollos), the time frame in which it was written was between 2 Thessalonians, 51 64-69ad and most likely to the Jews dispersed in Rome. Peter from James: More than any other book in the New Testament, James places the spotlight on 1 Corinthians, 55 the necessity for believers to act in accordance with their faith. Jesus’ half-brother (who became a follower after Jesus’ resurrection), was one of the leaders of the church at Letters 2 Corinthians, 56 Jerusalem, and wrote this letter in the same vein as the book of Proverbs to provoke the Jewish Christians to let their faith be seen by their works. He brought focus to practical Romans, 57 action in the life of faith. He encouraged God’s people to act like God’s people. Because Book of Acts ends John to James, a faith that does not produce real life change is a faith that is worthless. Colossians, 60-62 from He offered numerous practical examples to illustrate his point: faith endures in the Philemon, 60-62 midst of trials, calls on God for wisdom, bridles the tongue, sets aside wickedness, visits orphans and widows, and does not favor those who have money. -

The Jerusalem Council Acts 15 21 Council Conundrum Circle Every Fourth Word in the Paragraph

The Jerusalem Council Acts 15 • What does this story teach me about God STORY POINT: SALVATION COMES ONLY THROUGH FAITH IN JESUS. or the gospel? Paul and Barnabas had been sharing the gospel with many people—including • What does this story teach me about myself? Gentiles. But some people in the church began to teach that the Gentiles could • Are there any commands in this story to obey? not be saved unless they first followed some of the same rules How are they for God’s glory and my good? the Jews followed. • Are there any promises in this story to remember? How Paul and Barnabas disagreed, and the church do they help me trust and love God? leaders decided to meet in Jerusalem to talk. • How does this story help me to live on mission better? After a long discussion, Peter stood up and said to the group, “Brothers, God chose me to tell the good news to the Gentiles. They heard the good news, and they believed. God accepted them and gave them the Holy Spirit, just as He did for us. “We believe that the Jews and Gentiles are saved in the same way—by the grace of the Lord Jesus. FOLD “I think we should not cause trouble for the Gentiles who have trusted in Jesus. Instead, let’s write them a letter telling them the things they should not do.” So the church leaders wrote a letter to the Gentile believers. The leaders chose Judas and Silas to go to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas to deliver the letter. -

The Eschatology of the Warning in Hebrews 10:26–31

Tyndale Bulletin 53.1 (2002) 97-120. THE ESCHATOLOGY OF THE WARNING IN HEBREWS 10:26–31 Randall C. Gleason Summary The absence of NT damnation terminology in Hebrews calls into question the widely held assumption that the author’s purpose was to warn his readers of eternal judgement. Furthermore, to limit the warnings to a distant future judgement overlooks its nearness and diminishes its relevance to the first-century audience facing the dangers arising from the first Jewish revolt. There are many clues throughout the epistle that point to the physical threat posed by the coming Roman invasion to those Christians who lapsed back into Judaism. These clues point immediately to the destruction of Palestine, the city of Jerusalem and the Temple. These conclusions are confirmed by a close examination of the OT texts cited or alluded to in Hebrews 10:26–31. Rather than eternal destruction, the OT examples warn of physical judgement coming upon Israel because of covenant unfaithfulness. If they sought refuge in Judaism, the readers could suffer the same fate of the Jewish rebels by the Romans. However, the readers could avoid God’s wrath coming upon the Jewish nation by holding firm to their confession, bearing the reproach of Christ outside the camp (13:13), and looking to the heavenly city instead of Jerusalem now under the sentence of destruction (13:14). I. Introduction Though many have analysed the eschatology of Hebrews,1 few have discussed its importance to the controversial warning passages.2 Five 1 C.K. Barrett, ‘The Eschatology of the Epistle to the Hebrews’, The Background of the New Testament and Its Eschatology, eds. -

Disciplers Bible Studies LESSON 10 Christ's Perfect Sacrifice Fulfilled the Law Hebrews 10

HEBREWS Disciplers Bible Studies LESSON 10 Christ's Perfect Sacrifice Fulfilled the Law Hebrews 10 Introduction A. Seven Points Regarding Shortcomings of the Law – Hebrews 10:1-4 So far in the Book of Hebrews we have learned about our Great High Priest forever who is able to save to the 1. The law was a shadow - 10:1 uttermost (chapter 7), the true sanctuary in which He ministers under a new covenant (chapter 8), and the The law was only a shadow and never the substance of cleansing blood which opened the way for us to enter the good things to come. What were those good things? the heavenly sanctuary (chapter 9). They were forgiveness of sins, a right relationship with God, and a clear conscience. These were seen in the law A further truth, which will now be considered, is the in shadows but could never be grasped in reality. way by which Christ entered into the Holiest of All. What is the path that He took when He walked the 2. The law was not the very image – 10:1 way of the cross to shed His blood and pass through the veil into the inner sanctuary (the Holiest of All) to The law could not reflect perfectly the reality that was appear in the presence of God? What was it that gave to come. It was an image but only a shadowy image His sacrifice its worth? What secured His acceptance and not the very image. “When a man makes an image, before God as our High Priest? What is the spiritual it is but a dead thing. -

The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to The

Hebrews 1:1 1 Hebrews 1:13 THE EPISTLE OF PAUL THE APOSTLE TO THE HEBREWS 1 God, who at sundry times and in divers manners spake in time past unto the fathers by the prophets, 2 Hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son, whom he hath appointed heir of all things, by whom also he made the worlds; 3 Who being the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person, and upholding all things by the word of his power, when he had by himself purged our sins, sat down on the right hand of the Majesty on high; 4 Being made so much better than the angels, as he hath by inheritance obtained a more excellent name than they. 5 For unto which of the angels said he at any time, Thou art my Son, this day have I begotten thee? And again, I will be to him a Father, and he shall be to me a Son? 6 And again, when he bringeth in the firstbegotten into the world, he saith, And let all the angels of God worship him. 7 And of the angels he saith, Who maketh his angels spirits, and his ministers a flame of fire. 8 But unto the Son he saith, Thy throne, O God, is for ever and ever: a sceptre of righteousness is the sceptre of thy kingdom. 9 Thou hast loved righteousness, and hated iniquity; therefore God, even thy God, hath anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows. 10 And, Thou, Lord, in the beginning hast laid the foundation of the earth; and the heavens are the works of thine hands: 11 They shall perish; but thou remainest; and they all shall wax old as doth a garment; 12 And as a vesture shalt thou fold them up, and they shall be changed: but thou art the same, and thy years shall not fail. -

Leviticus Chapter 16 Day of Atonement

Leviticus Chapter 16 The Day of Atonement Ryrie writes: “The Day of Atonement, described in this chapter, was the most important of all the ordinances given to Israel because on that day atonement was made for all the sins of the entire congregation (vv. 16, 21, 30, 33), as well as for the sanctuary (vv. 16, 33). It took place on the tenth day of the seventh month (Tishri, v. 29), and fasting was required from the evening of the ninth day to the evening of the tenth day” (Ryrie Study Bible, p. 184) … The required public fasts were only three in number: the Day of Atonement; the day before Purim; and the ninth of Ab, commemorating the fall of Jerusalem (ibid. p. 1527). [Picture from www.prophecyunlocked.com/lesson8.html.] Leviticus 16: 1-2 Now the LORD spoke to Moses after the death of the two sons of Aaron, when they had approached the presence of the LORD and died. The LORD said to Moses: Tell your brother Aaron that he shall not enter at any time into the holy place inside the veil, before the mercy seat which is on the ark, or he will die; for I will appear in the cloud over the mercy seat. The context of the Day of Atonement for Aaron was the death of his sons. And the biblical text makes sure we notice that. This was no celebration. It was a time of mourning the dead, fasting, and the need to pay for sin. Then Aaron is warned that he, too, will die if he enters the Holy Place.