Hebrews 10:26-31 Teach a “Punishment Worse Than Death”?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?

Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship Volume 8 Article 2 May 2021 Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? Jonathan T. Priddy Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Priddy, Jonathan T. (2021) "Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?," Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 8 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Divinity at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? Cover Page Footnote Priddy, Jonathan T. (2021) “Hebrews 10:26-31: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation?,” Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: Vol. 7 , Article 4. This article is available in Diligence: Journal of the Liberty University Online Religion Capstone in Research and Scholarship: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/djrc/vol8/iss1/2 Priddy: Apostasy and Can Believers Lose Salvation? 1 Introduction The warning passage of Hebrews 10:26-31 is one of five warning passages throughout the book of Hebrews regarding apostasy. Hebrews 1:1-2:4; 3:7-12; 5:11-6:15; 10:26-31; and 12:25-27 are the five warning passages; the one being addressed in this paper is the fourth, and arguably the most serious and sobering. -

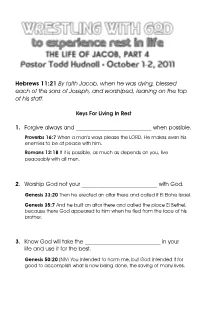

Hebrews 11:21 by Faith Jacob, When He Was Dying, Blessed Each of The

4. Trust that God is your __________________________ even when it doesn’t seem like it. Genesis 48:15 (NIV) “May the God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked, the God who has been my shepherd all my life to this day.” Hebrews 11:21 By faith Jacob, when he was dying, blessed 5. Expect God to fulfill His __________________________ without your manipulation. each of the sons of Joseph, and worshiped, leaning on the top of his staff. Genesis 48:14 (NIV) But Israel reached out his right hand and put it on Ephraim’s head, though he was the younger, and crossing his arms, he put his left hand on Manasseh’s head, even though Manasseh was Keys For Living In Rest the firstborn. 1. Forgive always and __________________________ when possible. Proverbs 16:7 When a man’s ways please the LORD, He makes even his enemies to be at peace with him. Group Discussion Questions Romans 12:18 If it is possible, as much as depends on you, live 1. Read Romans 12:18. What is the difference between living peaceably with all men. peaceably and being reconciled? Are there any relationships in your life where you need to establish peace? Are there any relationships in your life where you 2. Worship God not your __________________________ with God. need to reconcile? What do you think you need to do? Genesis 33:20 Then he erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel. 2. Why is it important to worship God and not your experience Genesis 35:7 And he built an altar there and called the place El Bethel, with God? Has that ever been a problem for you? Explain. -

The Book of Hebrews

The Book of Hebrews Introduction to Study: Who wrote the Epistle to the Hebrews? A. T. Robertson, in his Greek NT study, quotes Eusebius as saying, “who wrote the Epistle God only 1 knows.” Though there is an impressive list of early Bible students that attributed the epistle to the apostle Paul (i.e., Pantaenus [AD 180], Clement of Alexander [AD 187], Origen [AD 185], The Council of Antioch [AD 264], Jerome [AD 392], and Augustine of Hippo in North Africa), there is equally an impressive list of those who disagree. Tertullian [AD 190] ascribed the epistle of Hebrews to Barnabas. Those who support a Pauline epistle claim that the apostle wrote the book in the Hebrew language for the Hebrews and that Luke translated it into Greek. Still others claim that another author wrote the epistle and Paul translated it into Greek. Lastly, some claim that Paul provided the ideas for the epistle by inspiration and that one of his contemporaries (Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, Silas, Aquila, Mark, or Clement of Rome) actually composed the epistle. The fact of the matter is that we just do not have enough clear textual proof to make a precise unequivocal judgment one way or the other. The following notes will refer to the author as ‘the author of Hebrews,’ whether that be Paul or some other. Is the Book of Hebrews an Inspired Work? Bible skeptics have questioned the authenticity (canonicity) of Hebrews simply because of its unknown author. There are three proofs that should suffice the reader of the inspiration of Hebrews as it takes its rightful place in the NT. -

Hebrews 11-23-31

Hebrews 11-23-31 Prayer for illumination: please join me in prayer…. Sermon introduction: If you live long enough you will face a crisis. Many of you have faced multiple crises in the last year. Some of you have faced a health crisis. Some of you have faced a family crisis. Some of you have lost loved ones. Some of you have faced a work crisis. Some of you have faced a significant relational crisis. Some of you have faced a financial crisis. Some of you have experienced a school crisis. Unfortunately, crises come in all shapes and sizes. How do you respond when a crisis strikes? Some people panic, others plan like crazy, some work harder, others isolate themselves, manipulate others, or medicate with substances, food, or media. None of these responses brings joy and peace! How should we respond? This brings us to the book of Hebrews once again. The recipients of this letter faced a crisis. Hebrews 10:32–34 (ESV) — 32 But recall the former days when, after you were enlightened, you endured a hard struggle with sufferings, 33 sometimes being publicly exposed to reproach and affliction, and sometimes being partners with those so treated. 34 For you had compassion on those in prison, and you joyfully accepted the plundering of your property, since you knew that you yourselves had a better possession and an abiding one. The original audience experienced persecution and affliction simply for being Christians. Some even had their personal property vandalized. They were outcasts. This was a crisis. How should they respond to this crisis? How should you respond to crisis? We find the answer in Hebrews 11:23-31. -

8-02-20 Hebrews 10-26-31 Transcript

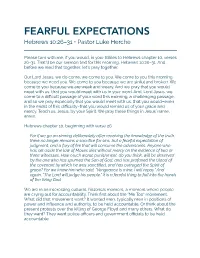

FEARFUL EXPECTATIONS Hebrews 10:26–31 • Pastor Luke Herche Please turn with me, if you would, in your Bibles to Hebrews chapter 10, verses 26–31. That'll be our sermon text for this morning, Hebrews 10:26–31. And before we read that together, let's pray together. Our Lord Jesus, we do come, we come to you. We come to you this morning because we need you. We come to you because we are sinful and broken. We come to you because we are weak and weary. And we pray that you would meet with us, that you would meet with us in your word. And, Lord Jesus, we come to a difficult passage of your word this morning, a challenging passage, and so we pray especially that you would meet with us, that you would–even in the midst of this difficulty–that you would remind us of your grace and mercy. Teach us, Jesus, by your Spirit. We pray these things in Jesus’ name, amen. Hebrews chapter 10, beginning with verse 26. For if we go on sinning deliberately after receiving the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a fearful expectation of judgment, and a fury of fire that will consume the adversaries. Anyone who has set aside the law of Moses dies without mercy on the evidence of two or three witnesses. How much worse punishment, do you think, will be deserved by the one who has spurned the Son of God, and has profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified, and has outraged the Spirit of grace? For we know him who said, "Vengeance is mine; I will repay." And again, "The Lord will judge his people." It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God. -

James and His Readers James 1:1

Lesson 1 James and His Readers James 1:1 An Epistle On Christian Living The book of James has most often been placed in a group with 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2 and 3 John and Jude. The seven books, as a group, are often called the general epistles. This title comes from the fact that they all are written to the church in general or a wide section of the church, instead of to a church in a specific city. In many ways, this epistle could be called a commentary on the sermon on the mount. James reveals the very heart of the gospel. He tells Christians how to live daily for the Master. Coffman says, "There is no similar portion of the sacred scriptures so surcharged with the mind of Christ as is the Epistle of James." Shelly titles his book on James What Christian Living Is All About and suggests James 1:27 sounds the theme of the book, which is pure and undefiled religion. James, The Lord's Brother The author identifies himself as James (James 1:1). Four men in the New Testament are called James. One was the father of Judas, not Iscariot (Luke 6:16; Acts 1:13). It seems unlikely that this is our author since we know so little of him. The author of this book was so well known to the early church that he only signed his name. James, the son of Alphaeus, was one of the Lord's apostles (Acts 1:13; Luke 6:15; Mark 3:18; Matthew 10:32). -

Livingbyfaith-Print.Pdf

Two men stood side by side on a dock one day, peering Otherwise, there’s no way you can navigate through today out into the broad ocean. One looked out and said, “I see a and make it to tomorrow! ship!” The other guy turned his gaze in the same direction and declared, “There’s no ship out there.” “Yes there is,” the first man insisted. “Look,” his friend countered, “I just had an eye exam. I’ve got perfect twenty-twenty vision and I’m telling you, I don’t see a ship.” “Take my word for it. There is a ship.” “How can you be so sure?” the second man asked, squinting hard as he looked out to sea. “I see it clearly through my binoculars.” Your Perspective To a great degree, living a successful Christian life is a No Turning Back matter of perspective. The clarity of your vision can make all the difference and sharp-sightedness often depends on The writer found himself addressing a most perplexing the focusing power of the lens you are using. problem. He was faced with a congregation of people who were contemplating quitting the Christian faith. Even distant images can be brought into crystal clarity with They were considering throwing in the towel because the right optics. In the same way, if we look at our lives they were no longer sure that following the path was through the lens of Scripture, we might discover an ocean worth the pain. They thought that it might just be too liner we failed to notice earlier. -

“Three to Get Ready” Dr. David Jeremiah

Bringing it Home “Three to Get Ready” Dr. David Jeremiah 1. Dr. Jeremiah said, “Love and good works do not just happen. They need to be September 25, 2011 ‘stimulated.’” How can we, as believers, stimulate love and good works in Hebrews 10:19-25 ourselves as well as in others? What does a stimulation to love and good works look like? Sound like? Small Group Questions I. Let us draw near in faith - Hebrews 10:19-22 A. The call to fellowship with God - Heb. 10:22a; James 4:8; Ps. 73:28 B. The confidence of fellowship with God - Heb. 10:19a; 9:7; 4:16; 7:25 2. Today you are in one of two boats; an anchored boat (in fellowship with God and His people) or an unanchored boat (out of fellowship with God and/or His C. The cost of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:19b people). D. The contrast of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:20a a. If you are in an unanchored boat, what decision do you need to make so that you can climb out of your boat and into one that is anchored? E. The closeness of fellowship with God - Heb. 10:20b; Rom. 8:31-34 What specific storm are you facing? How would facing this storm with God, or His people, change your perspective on the storm? F. The creator of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:21 G. The certainty of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:22a; James 1:6-8 H. The cleansing of fellowship with God - Hebrews 10:22b; 9:13-14; b. -

Better Than the Blood of Abel? Some Remarks on Abel in Hebrews 12:24

Tyndale Bulletin 67.1 (2016) 127-136 BETTER THAN THE BLOOD OF ABEL? SOME REMARKS ON ABEL IN HEBREWS 12:24 Kyu Seop Kim ([email protected]) Summary The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, the meaning of ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. This study argues that τὸν Ἅβελ in Hebrews 12:24 refers to Abel as an example who speaks to us through his right observation of the cult. Accordingly, Hebrews 12:24b means that Christ’s cult is superior to the Jewish ritual. This interpretation fits exactly with the adjacent context contrasting Sinai and Zion symbols. 1. Introduction The sudden mention of Abel in Hebrews 12:24 has elicited a multiplicity of interpretations, but despite its significance, this topic has not attracted the careful attention that it deserves. Traditionally, scholars assert that ‘Abel’ (τὸν Ἅβελ) in Hebrews 12:24 refers to ‘the blood of Abel’.1 Most Bible translators also read ‘than Abel’ (παρὰ τὸν 1 E.g. Ceslas Spicq, L’Épître aux Hébreux, (Paris: Libraire Lecoffee, 1952–53), 2:409-10; Jonathan I. Griffiths, Hebrews and Divine Speech, LNTS (London: T & T Clark, 2014), 143-44; B. F. Westcott, The Epistle to the Hebrews (London: Macmillan, 1892), 417; Harold W. Attridge, Hebrews, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 377; James Moffatt, The Epistle to the Hebrews, ICC (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1924); Hugh Montefiore, A Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, BNTC (London: A & C Black, 1964), 233; R. -

Of 9 the FAITH of MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses

THE FAITH OF MOSES Hebrews 11:23-28 Key Verses: 11:24,25 "By faith Moses, when he had grown up, refused to be known as the son of Pharaoh's daughter. He chose to be mistreated along with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a short time." Moses is known as the most outstanding leader of all leaders who have lived in the world. Moses received the highest education in the palace of the Egyptian Empire for 40 years. For the growth of his inner character, he received another 40 years of humbleness training in the wilderness among seven daughters of Jethro, tending Jethro's flock of sheep. They call this humbleness training or the wilderness seminary. When Moses had completed 80 years of training altogether, God could use him greatly. In the Bible, Moses was known as a servant of God who worked harder than any others to lead his rebellious people; he died without seeing the promised land, though it had been his only dream to see it. There is a saying, "Moses dipped out all the water of a lake, then David caught all the fish and Solomon cooked and ate them all." But the author of Hebrews says that Moses is great because he had faith that pleases God. I. The faith of Moses' parents (23) First, they saw he was no ordinary child (23a). Read verse 23. "By faith Moses parents hid him for three months after he was born, because they saw he was no ordinary child, and they were not afraid of the king's Page 1 of 9 edict." Many great men in history were born in adverse circumstances or in tragic human conditions. -

Handfuls on Purpose Sample

HANDFULS ON PURPOSE SAMPLE Contents NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES PAGES Philemon, .. 9 Hebrews, .. 15 James, .. 24 1 Peter, .. 46 2 Peter, . 92 EXPOSITORY STUDIES- The Penitential Psalm—Psalm 51 113 The Golden Passional--Isaiah 53, 133 The Death of Christ, 167 Gospel Studies, 2OO Bible Readings,. 261 Studies for Believers, 281 Handfuls on Purpose New Testament Studies Philemon This is the briefest of all Paul's Epistles. It is the only sample of the Apostle's private correspondence that has been preserved. It is known as "The Courteous Epistle. " Its object was to persuade Philemon not to punish, but reinstate, his runaway slave, called Onesimus, and as he was now converted, treat him as a brother in the Lord. THE TASK AND ITS ACCOMPLISHMENT. PHILEMON. I. The Task. Invariably, in those days, runaway slaves were crucified. Paul must try to conciliate the master-Philemon—without humiliating the servant—Onesimus; to commend the repentant wrong-doer, without extenuating his offence; thus he must balance the claims of justice and mercy. II. Its Solution. 1. Touching Philemon's heart by several times mentioning that he was a prisoner for the Gospel's sake. 2. Frankly and fully recognised Philemon's most excellent Christian character, thus making it difficult for him to refuse to live up to his reputation, and to lead him to deal graciously with the defaulter. 3. Delayed mentioning the name of the penitent until he had paved the way. 4. Referred to Onesimus as his "son," thus establishing the new kinship in Christ. 5. After presenting his request, assumed Philemon would do as he had requested (21) . -

ELEVEN – Hebrews 11 Sermon Series

ELEVEN – Hebrews 11 sermon series MAKING GOD SMILE Series: Eleven Date: April 7, 2018 Scripture: Hebrews 11 Key sermon points: • The essence of audacious confidence • That’s not faith • Faith is an awareness of the invisible world that produces conviction leading to action • Faith wagers on God’s goodness • Faith prioritizes relationship with God above all • Faith surrenders personal reputation • Faith makes Him smile • A step of faith NOW FAITH IS THE ASSURANCE OF THINGS HOPED FOR, THE CONVICTION OF THINGS NOT SEEN, FOR BY IT THE PEOPLE HAVE ALL RECEIVED THEIR COMMENDATION. BY FAITH WE UNDERSTAND THAT THE UNIVERSE WAS CREATED BY THE WORD OF GOD, SO THAT WHAT IS SEEN WAS NOT MADE OUT OF THINGS THAT ARE VISIBLE BY FAITH. ABEL OFFERED TO GET A MORE ACCEPTABLE SACRIFICE THAN CAIN, THROUGH WHICH HE WAS COMMENDED AS RIGHTEOUS. GOD COMMENDING HIM BY ACCEPTING HIS GIFTS AND THROUGH HIS FAITH, THOUGH HE DIED, HE STILL SPEAKS. BY FAITH ENOCH WAS TAKEN UP SO THAT HE SHOULD NOT SEE DEATH AND HE WAS NOT FOUND BECAUSE GOD HAD TAKEN HIM. NOW BEFORE HE WAS TAKEN, HE WAS COMMENDED AS HAVING PLEASED GOD AND WITHOUT FAITH IT'S IMPOSSIBLE TO PLEASE HIM FOR WHOEVER WHO DRAW NEAR TO GOD MUST BELIEVE THAT HE EXISTS AND THAT HE REWARDS THOSE WHO SEEK HIM. BY FAITH NOAH BEING WARNED BY GOD CONCERNING EVENTS AS YET UNSEEN, IN REVERENT FEAR CONSTRUCTED AN ARK FOR THE SAVING OF HIS HOUSEHOLD AND BY THIS HE CONDEMNED THE WORLD AND BECAME AN HEIR OF THE RIGHTEOUSNESS THAT COMES BY FAITH.