Amicus Brief of the National Conference of State Legislators, Even Though the State Itself Did Not Make That Argument); Kansas V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 State Relations Summary

SESSION SUMMARY 2018 2018 STATE RELATIONS SESSION SUMMARY The 2018 Legislative Session convened on February 20, The legislature passed a bonding bill in the final with Republicans continuing to hold a majority in the moments of session, and the governor signed the bill House and Senate following two special elections. This into law; however, no agreement was reached between year also marked DFLer Mark Dayton’s last legislative the legislature and the governor on the supplemental session as governor; he will not seek re-election this fall. budget. As a result, the governor vetoed the legislature’s omnibus supplemental budget bill a few days after the Typically, the legislature focuses on capital investment constitutionally mandated adjournment date of May 21. projects in even numbered years. The House and Senate The governor also vetoed an omnibus tax bill designed capital investment committees conducted many tours to conform Minnesota’s tax system to newly enacted tax last summer and fall of proposed bonding projects reforms on the federal level. throughout the state. Additionally, the Budget and Economic Forecast projected a $329 million surplus, All Minnesota House seats are up for election this and the governor, Senate, and House pursued a November, and Minnesotans will also elect a new supplemental budget bill. governor. Several members of the House and Senate have announced their intentions to retire or pursue other The University of Minnesota submitted both a capital elected offices. The legislature is scheduled to convene request and a supplemental budget request to the state. for the 91st legislative session on January 8, 2019. -

Department of Transportation 18

DEPARTMENT OF 18 - 0293 395 John Ire land Boulevard m, TRANSPORTATION St. Paul, M N 55155 ( March 1, 2018 Via Email Sen. Scott Newman, Chair, Senate Transportation Sen. Bill Weber, Chair, Senate Agriculture, Rural Finance and Policy Development, and Housing Policy Sen. Scott Dibble, Ranking Minority Member, Senate Sen. Foung Hawj, Ranking Minority Member, Transportation Finance and Policy Agriculture, Rural Development, and Housing Policy Rep. Paul Torkelson, Chair, House Transportation Rep. Paul Anderson, Chair, House Agriculture Policy Finance Rep . David Bly, DFL Lead, House Agriculture Policy Rep. Frank Hornstein, DFL Lead, House Transportation Finance Sen. Bill lngebrigtsen, Chair, Senate Environment and Natural Resources Finance Rep. Linda Runbeck, Chair, House Transportation and Sen. David Tomassoni, Ranking Minority Member, Regional Governance Policy Senate Environment and Natural Resources Finance ( Rep. Connie Bernardy, DFL Lead, House Transportation and Regional Governance Policy Rep. Dan Fabi~n, Chair, House Environment and Natural Resources Policy and Finance Sen. Torrey Westrom, Chair, Senate Agriculture, Rep. Rick Hansen, DFL Lead, House Environment and Rural Development, and Housing Finance Natural Resources Policy and Finance Sen. Kari Dzie~zic, Ranking Minority Member, Senate Agriculture, Rural Development, and Housing Finance Sen. Carrie Rudd, Chair, Senate Environment and Natural Resources Policy and Legacy Finance Sen. Chris Eaton, Ranking Minority Member, Senate Rep. Rod Hamilton, Chair, House Agriculture Finance -

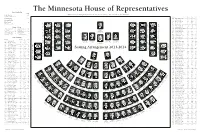

Minnesota House of Representatives Seating Chart

The Minnesota House of Representatives House Leadership Seat Paul Thissen ........................................... 139 Minnesota House of Representatives Public Information Services, 651-296-2146 or 800-657-3550 Speaker of the House District Room* 296- Seat Erin Murphy ........................................... 102 60B Kahn, Phyllis (DFL) ............365 ....... 4257 ....... 97 Majority Leader 21A Kelly, Tim (R) ......................335 ....... 8635 ....... 12 53B Kieffer, Andrea (R) ..............213 ....... 1147 ....... 43 Minnetonka—44B Kurt Daudt ............................................... 23 Shoreview—42B Murdock—17A Jason Isaacson John Benson 1B Kiel, Debra (R) ....................337 ....... 5091 ....... 30 Andrew Falk Seat 124 Seat 135 Minority Leader Seat 129 9B Kresha, Ron (R) ...................329 ....... 4247 ....... 53 Seat 1 Seat 6 41B Laine, Carolyn (DFL) ..........485 ....... 4331 ....... 82 Seat 11 Joe Hoppe Mayer—47A Ernie Leidiger Mary Franson Chaska—47B House Officers Alexandria—8B 47A Leidiger, Ernie (R) ...............317 ....... 4282 ......... 1 Mary Sawatzky Faribault—24B Willmar—17B Virginia—6B Albin A. Mathiowetz ....... 142 Timothy M. Johnson ....... 141 Jason Metsa 50B Lenczewski, Ann (DFL) ......509 ....... 4218 ....... 91 Seat 123 Seat 128 Seat 134 Patti Fritz Seat 139 Chief Clerk Desk Clerk Paul Thissen 66B Lesch, John (DFL) ...............537 ....... 4224 ....... 71 Patrick D. Murphy .......... 143 David G. Surdez ............. 140 Minneapolis—61B Seat 7 Seat 2 26A Liebling, Tina (DFL) ...........367 ....... 0573 ....... 90 Seat 12 Speaker of the House Kelly Tim Bob Dettmer 1st Asst. Chief Clerk Legislative Clerk Bob Barrett Lindstrom—32B Red Wing—21A Forest Lake—39A 4A Lien, Ben (DFL) ..................525 ....... 5515 ....... 86 Gail C. Romanowski ....... 144 Travis Reese ...................... 69 South St. Paul—52A Woodbury—53A Richfield—50A 2nd Asst. Chief Clerk Chief Sergeant-at-Arms Linda Slocum 43B Lillie, Leon (DFL) ...............371 ...... -

Minnesota Legislature Member Roster

2013-2014 Minnesota House of Representatives Members-elect Phone Phone District Member/Party Room* 651-296- District Member/Party Room* 651-296- 35A Abeler, Jim (R) ...............................................479 ................................. 1729 66B Lesch, John (DFL) .........................................315 ................................. 4224 55B Albright, Tony (R) ............................................................................7-9010† 26A Liebling, Tina (DFL) .....................................357 ................................. 0573 62B Allen, Susan (DFL) ........................................389 ................................. 7152 4A Lien, Ben (DFL) .................................................................................7-9001† 9A Anderson, Mark (R) ........................................................................7-9010† 43B Lillie, Leon (DFL) ...........................................281 ................................. 1188 12B Anderson, Paul (R) .......................................445 ................................. 4317 60A Loeffler, Diane (DFL) ...................................335 ................................. 4219 44A Anderson, Sarah (R) ....................................549 ................................. 5511 39B Lohmer, Kathy (R) ........................................521 ................................. 4244 5B Anzelc, Tom (DFL) ........................................307 ................................. 4936 48B Loon, Jenifer (R) ............................................403 -

Campaign Finance PCR Report

Total Pages: 23 Jul 24, 2018 Campaign Finance PCR Report Filing Period: 12/31/2018 Candidate Candidate Number of Committee Name Term Date First Name Last Name Requests Lyndon R Carlson Campaign 50 Committee Lyndon Carlson Mary Murphy Volunteer Committee Mary Murphy 1 Pelowski (Gene) Volunteer Committee Gene Pelowski Jr 1 Jean Wagenius Volunteer Committee Jean Wagenius 3 Senator (John) Marty Volunteer 2 Committee John Marty Ron Erhardt Volunteer Committee Ronnie (Ron) Erhardt 1 (Tom) Hackbarth Volunteer Committee Thomas Hackbarth 5 Urdahl (Dean) Volunteer Committee Dean Urdahl 43 Volunteers for (Larry) Nornes Larry (Bud) Nornes 3 Limmer (Warren) for Senate 1 Committee Warren Limmer Volunteers for Gunther (Robert) Robert Gunther 2 Wiger (Charles) for Senate Volunteer 3 Committee Charles (Chuck) Wiger Friends of (Michelle) Fischbach Michelle Fischbach 36 Masin (Sandra) Campaign Committee Sandra Masin 5 Committee for (Sondra) Erickson Sondra Erickson 39 Marquart (Paul) Volunteer Committee Paul Marquart 27 Ann Rest for Senate Committee Ann Rest 2 Tomassoni (David) for State Senate David Tomassoni 5 Julie Rosen for State Senate Julie Rosen 1 Peppin (Joyce) Volunteer Committee Joyce Peppin 8 Mike Nelson Volunteer Committee Michael Nelson 19 Hornstein (Frank) Volunteer Committee Frank Hornstein 1 Poppe (Jeanne) for the People 45 Committee Jeanne Poppe Melissa Hortman Campaign Committee Melissa Hortman 71 Liebling (Tina) for State House Tina Liebling 13 Mahoney (Tim) for House Timothy Mahoney 5 Leslie Davis for Governor Leslie Davis 4 Garofalo -

News Release

OFFICE OF GOVERNOR TIM PAWLENTY 130 State Capitol ♦ Saint Paul, MN 55155 ♦ (651) 296-0001 NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Brian McClung January 6, 2010 (651) 296-0001 GOVERNOR PAWLENTY APPOINTS JONES TO AGRICULTURAL CHEMICAL RESPONSE COMPENSATION BOARD Saint Paul – Governor Tim Pawlenty today announced the appointment of Kevin M. Jones to the Agricultural Chemical Response Compensation Board. Jones, of St. James, is the general manager of NuWay Cooperative in Trimont. He has held a number of positions with NuWay during the 15-and-a-half years he has been with the Coop. Previously, he worked in the agronomy and feed division with Watonwan Farm Service, and worked on a family farm. Jones earned an agribusiness management degree from Ridgewater College in Willmar, and is a certified crop advisor. He is a member of the Farm Bureau, Statewide Managers Association, Southern Minnesota Managers Association, Minnesota Petroleum Association, Minnesota Propane Gas Association, Cooperative Network, and Minnesota Crop Protection Retailers. Jones replaces Jeff Like on the Agricultural Chemical Response Compensation Board as a representative of agricultural chemical retailers to complete a four-year term that expires on January 2, 2012. The Agricultural Chemical Response and Reimbursement Account (ACRRA) was created under the 1989 Minnesota Ground Water Protection Act to provide financial assistance to cleanup agricultural chemical contamination. The program is funded through annual surcharges on pesticide and fertilizer sales, and on applicator and dealer licenses. The ACRRA funds are administered by the Agricultural Chemical Response Compensation Board. The five-member board consists of representatives from the Minnesota Departments of Agriculture and Commerce, and three members appointed by the Governor, including a representative of farmers, agricultural chemical manufacturers and wholesalers, and dealers who sell agricultural chemicals at retail. -

Office Memorandum

Office Memorandum Date: December 21, 2016 To: Commissioners and Agency Heads From: Commissioner Myron Frans Phone: 651-201-8011 Subject: State Government Special Revenue (1200) Fund I am writing to you because your agency receives an appropriation from the State Government Special Revenue Fund (Fund 1200 in SWIFT). We are projecting a deficit in this fund and will need to take steps to resolve the deficit. Based on the November Forecast Consolidated Fund Statement, Minnesota Management and Budget (MMB) is now projecting that expenditures in this fund will exceed resources in the current fiscal year. Because of this, we are now anticipating a projected deficit of $2,877,000 in fiscal year 2017 in the 1200 Fund. The projected deficit is expected to grow by approximately $2 million each year from FY 2018-21. I am required by statute (MS 16A.152) to take action to resolve this deficit. I am asking for your cooperation to help my staff identify solutions to prevent the projected deficit from occurring. In the coming weeks, your Executive Budget Officer (EBO) from MMB will contact your agency to develop an understanding of current spending obligations and identify possible cancellations and remaining balances that may be available in order to resolve the deficit in the fund. I have asked my team to work with your agency so that we may develop a solution within the next several weeks. If you have any questions, please contact your EBO. We intend to publish the November Forecast Consolidated Funds Statement on December 22, 2016. This publication will officially report the anticipated deficit. -

Financial Statements

Financial Statements Legislative Coordinating Commission St. Paul, Minnesota For the Year Ended June 30, 2017 THIS PAGE IS LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY Legislative Coordinating Commission St. Paul, Minnesota Table of Contents For the Year Ended June 30, 2017 Page No. Introductory Section Organization 7 Financial Section Independent Auditor’s Report 11 Management Discussion and Analysis 15 Basic Financial Statements Government-wide Financial Statements Statement of Net Position 22 Statement of Activities 23 Fund Financial Statements Governmental Funds Balance Sheet and Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Net Position 26 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances and Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances 27 Combining Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances - Budget and Actual 28 Notes to the Financial Statements 29 Required Supplementary Information Schedule of Funding Progress and Employer Contributions 40 Combining and Individual Fund Financial Statements and Schedules Governmental Funds Combining Balance Sheet 42 Combining Schedule of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances 46 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances - Budget and Actual General Support 51 Pensions and Retirement 52 Minnesota Resources 53 Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council 54 General Carry Forward 55 Energy Commission 56 Public Info TV & Internet 57 Legislative Reference Library 58 Revisor’s Carry Forward 59 Revisor of -

M, DE PART ME NT of HUMAN SERVICES

DE PART ME NT OF m, HUMAN SERVICES Minnesota Department of Human Services Acting Commissioner Chuck Johnson Post Office Box 64998 St. Paul, Minnesota 55164-0998 Representative Matt Dean, Chair Health and Human Services Finance Committee 401 State Office Building 100 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. St. Paul, MN 55155 February 27, 2018 Dear Rep. Matt Dean, I am writing to express concerns with HF2725, a bill that would repeal MNsure and create a new county based eligibility determination system for Medical Assistance (MA) and MinnesotaCare. This system would replace the Minnesota Eligibility Technology System (METS) and MAXIS and require counties to administer MinnesotaCare. The bill also establishes an information technology steering committee to direct development of the new system. The goal and impact of the bill is unclear as it is currently written. We are still assessing the potential unintended effects and disruptions this bill will create for our stakeholders, partners and the individuals we serve. Below are some of our preliminary concerns. OHS is designated as the single state agency required to administer and oversee the Medicaid (Medical Assistance) program. OHS ensures compliance with federal eligibility rules and establishes processes and procedures to ensure Minnesotans are able to enroll. The bill is unclear about how Medical Assistance and MinnesotaCare eligibility will be assessed and determined and how authority would be .divided between OHS, counties and the commissioner of Revenue. It is unlikely the federal government would approve of such a structure. It is also unclear how we would transition from METS to the new proposed system, or how the resources currently devoted to METS would impact the county-developed system. -

MSSA Services Yes

Volume 33 Issue 6 June 2018 Monthly Publication of the Minnesota Service Station and Convenience Store Association B20 Mandate Temporary Suspension ends on June 30, 2018 The original suspension period was from MN Lottery May 21, 2018 thru June 30, 2018. Effective July 1, 2018, all diesel fuel sold or offered for Minnesota Election Update sale in Minnesota for use in internal combus- June 2018 tion engines must contain at least then per- cent (10%) biodiesel fuel oil by volume. U.S. States Pressure Automak- ers on EVs As a retailer, can I wait until July 1, 2018 to start taking deliveries of B20 again? Enbridge “Our Commitment to Minnesota” No. By July 1, 2018 all diesel fuel sold or offered for sale in Minnesota for use in internal combustion engines must again con- New Members tain twenty percent (20%) biodiesel fuel oil by volume. The tempo- rary suspension was timed to allow stations approximately two WEX Evolves Fuel Payments weeks to turn their storage tanks over after biodiesel supply is ex- from Plastic to Phone pected to return to normal production levels. •Stations should start taking deliveries of B20 before June 30, so Counteracting Declining that the diesel fuel dispensed at their pumps contains twenty percent Customer Acquisition Rates in (20%) biodiesel by volume on July 1. Auto Repair •Any fuel delivered to fleets, farms, and other end users after June, MSSA Annual Golf Outing 30th, must contain twenty percent (20%) by volume. Reminder Will the Weights & Measures Division continue to enforce the biodiesel mandate during the B20 temporary suspension? MSSA Services Yes. -

Senate File 959 (EAB Provisions, Senate/House Environment

MEMORANDUM May 6, 2021 Senator Bill Ingebrigtsen Representative Rick Hansen Senator Carrie Ruud Representative Ami Wazlawik Senator Justin Eichorn Representative Kelly Morrison Senator David Tomassoni Representative Peter Fischer Senator Torrey Westrom Representative Josh Heintzeman Dear Members of the Environment and Natural Resources Conference Committee (SF959): The Partnership on Waste and Energy (Partnership) is a Joint Powers Board of Hennepin, Ramsey and Washington counties. We seek to end waste, promote renewable energy and enhance the health and resiliency of communities we serve while advancing equity and responding to the challenges of a changing climate. In a separate letter addressed to the committee, the Partnership included support for certain Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) provisions amidst comments on several other provisions in the Senate and House omnibus bills currently being deliberated in the committee. We would like to call specific attention to these EAB provisions and emphasize our strong support. EAB is now established in at least 27 Minnesota counties and continues to spread. Communities are removing and replacing ash trees as quickly as funding will allow to slow the spread of EAB. The challenge of properly managing the surge of waste wood created as we battle EAB is one of the urgent concerns of the Partnership. State law prohibits landfilling wood waste. Wood waste cannot be sent to MSW waste-to-energy facilities. Open burning, even if it were allowed, creates fire dangers and poor air quality, adversely impacting human health. The Partnership urges the conferees to adopt the following provisions to increase efforts to slow the spread of EAB and slow the rate of increase of wood waste. -

What Percentage of Incumbent Minnesota Legislators Are Returned to Office After Each General Election?

Minnesota Legislative Reference Library www.leg.mn/lrl What Percentage of Incumbent Minnesota Legislators Are Returned to Office After Each General Election? (What percentage of Minnesota legislators who run for re-election win?) Election Date: November 2, 2010 Legislative Chamber: House Number of incumbents who ran: 119 134 Total number of legislators in the chamber Minus 15 Number of incumbents who did not run Equals 119 Number of incumbents who ran Number of incumbents who were defeated: 21 36 Number of new legislators after election Minus 15 Number of incumbents who did not run Equals 21 Number of incumbents who were defeated Number of incumbents who won: 98 119 Number of incumbents who ran Minus 21 Number of incumbents who were defeated Equals 98 Number of incumbents who won Percent of incumbents re-elected: 82.4 % 98 Number of incumbents who won Divided by 119 Number of incumbents who ran Equals .8235 x 100 = 82.35 Percent of incumbents re-elected What Percentage of Incumbent Minnesota Legislators Are Returned to Office After Each General Election? (What percentage of Minnesota legislators who run for re-election win?) Election Date: November 2, 2010 Legislative Chamber: Senate Number of incumbents who ran: 58 67 Total number of legislators in the chamber Minus 9 Number of incumbents who did not run Equals 58 Number of incumbents who ran Number of incumbents who were defeated: 15 24 Number of new legislators after election Minus 9 Number of incumbents who did not run Equals 15 Number of incumbents who were defeated Number of incumbents