Coffee, Beer + Nikon.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey

06-ORD 70H-002AA 7 Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey - 2005 Survey - September 2006 Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Preface The survey on “Japanese manufacturing affiliates in Europe and Turkey” has been conducted 22 times since the first survey in 1983*. The latest survey, carried out from January 2006 to February 2006 targeting 16 countries in Western Europe, 8 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and Turkey, focused on business trends and future prospects in each country, procurement of materials, production, sales, and management problems, effects of EU environmental regulations, etc. The survey revealed that as of the end of 2005 there were a total of 1,008 Japanese manufacturing affiliates operating in the surveyed region --- 818 in Western Europe, 174 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 16 in Turkey. Of this total, 291 affiliates --- 284 in Western Europe, 6 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 1 in Turkey --- also operate R & D or design centers. Also, the number of Japanese affiliates who operate only R & D or design centers in the surveyed region (no manufacturing operations) totaled 129 affiliates --- 125 in Western Europe and 4 in Central and Eastern Europe. In this survey we put emphasis on the effects of EU environmental regulations on Japanese manufacturing affiliates. We would like to express our great appreciation to the affiliates concerned for their kind cooperation, which have enabled us over the years to constantly improve the survey and report on the results. We hope that the affiliates and those who are interested in business development in Europe and/or Turkey will find this report useful. -

Vol 1 No 2 Autumn 2004 Photo by Duncan Mcewan

Vol 1 No 2 photoWORLD Autumn 2004 Photo by Duncan McEwan photoworld2cover.indd 1 27/8/04 8:52:39 pm 10% off repairs and servicing for Photoworld club members he Konica Minolta Photoworld TClub Cam era Check Scheme Information on this page is printed in each General In sur ance Com pa ny. Some runs all year round, taking the sea- Checks & parts for older mod els are now no sonal load off the service department. issue for your benefi t – please use it. longer avail a ble, and Konica Minolta Service will give Club Checks have to re strict these war ran ties to ‘absolute priority’ and these Call 01908 200400 for service! the list be low. If your equip ment is will nor mal ly be accomplished more re cent, but now out of war ran ty, with in 3-4 days of receipt. Warranties call the Serv ice Dept for ad vice This is great news but please fi lm transport, AF operation, self Extended Warranty on 01908 200400. If you wish to be sure to allow a little more timer, fl ash syn chro ni sa tion and fi nd out more about the warranty time – and please do not send all other key op er a tion al aspects The Minolta Extended War ran ty terms, ring Do mes tic & Gen er al’s equip ment to the Kel so address. of the camera. External cleaning Scheme is available on new equip- Hel pline on 0181 944 4944. As a Photoworld subscriber you of camera and lens is undertaken, ment. -

Organization Sector Report Title Publication Year Report Type

GRI Reports List 2012(Japan) last updated: April 2013 Organization Sector Report Title Publication Year Report type Application Level Status Adeka Chemicals CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Advantest Technology Hardware Corporate Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced AEON Retailers Environmental and Social Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Aeon Retailers Environmental & Social Initiatives 2012 2012 Non - GRI Aishin Seiki Equipment Aisin Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Ajinomoto Food and Beverage Products Sustainability Report 2012 2012 Non - GRI All Nippon Airways Coompany Limited Aviation Annual Report 2012 Non - GRI Asahi Glass Company Chemicals AGC Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Asahi Group Holdings Food and Beverage Products CSR Communication Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Asahi Kasei Chemicals CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Astellas Pharma Health Care Products Annual Report 2012 2012 GRI - G3.1 B Self-declared azbil Conglomerates azbil Report 2012 2012 Non - GRI Benesse Holdings, Inc. Other Benesse Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Bridgestone Chemicals CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Brother Technology Hardware CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Canon Technology Hardware Sustainability Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Casio Consumer Durables Sustainability Report 2012 2012 GRI - G3.1 B Self-declared Chiyoda Corporation Construction CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Chubu Electric Power Energy Annual Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced Citizen Holdings Conglomerates CSR Report 2012 2012 GRI - Referenced -

Page 16 of 128 Exhibit No. Description Deposition

Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 1 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-168 7/16/2003, Technical Reference Napoli Ex. Manual [DM270] (EKCCCI007053- 132 836) PTX-169 2003, Data Sheet for TMS320DM270 Processor (AX200153-55) PTX-170 10/30/2002, DM270 Preliminary Napoli Ex. Register Manual Rev. b0.6 131 (EKCCCI001305-495) PTX-171 TI DM270 Imx Hardware Akiyama Programming Interface, Version 0.0 Ex. 312 (EKCNYII005007249-260) PTX-172 3/3/2003, DM270 Preliminary Data Ohtake Ex. Sheet Rev. b0.7C (EKCCCI008094- 123 131) PTX-173 Fact Sheet for TMS320DM270 Lacks Processor (AX200150-52) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-174 6/04, Data Sheet rev 0.5 for Hynix Ligler Ex. Lacks HY57V561620C[L]T[P] (AX200163- 13 (ITC) authenticity; 74) Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-175 Sharp RJ21T3AA0PT Data Sheet Hearsay; (EKCCCI017389-413) Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance PTX-176 DX7630 Thumbnail Test Lacks (AXD022568-81) authenticity; Hearsay; Lacks foundation; Lacks relevance; Inaccurate/ incomplete description PTX-177 1/11/2005, DM270 IP Chain ver. 0.7 Yoshikawa with translation (EKC001021025-31, Ex. 348 AX211033-42) PTX-178 1/26/2004, Bud Camera F/W Task Lacks foundation; Interface Capture Main <-> Image ISR Lacks relevance (DX7630) ver. 0.07 / Takeshi Domen with translation (EKCCCI002404-19, AX211607-26) Page 16 of 128 Case 1:04-cv-01373-KAJ Document 467-2 Filed 10/23/2006 Page 2 of 140 Exhibit Description Deposition Objections No. Ex. No. PTX-179 2/17/2003, Budweiser Camera EXIF Akiyama Lacks foundation; File Access Library Spec (DX7630) Ex. -

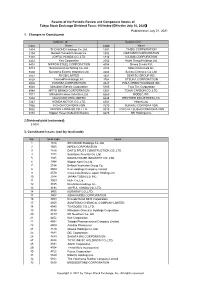

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

Notice of Investment Payment Completion and Service Commencement for New J/V in the Container Shipping Business

Notice of Investment Payment Completion and Service Commencement for New J/V in the Container Shipping Business April 2, 2018 Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. Eizo Murakami, President & CEO Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. Junichiro Ikeda, President & CEO Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha Tadaaki Naito, President Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd., Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd., and Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha today announced the completion of payment for investment in their new joint venture in the container shipping business, Ocean Network Express Pte. Ltd. (ONE), which was established in July 2017, with service commencing on April 1, 2018, as follows. 1. Payment of investment Investee: Ocean Network Express Pte. Ltd. (location: Singapore) Amount of investment: Total US$3.0 billion (The following changes have been made to the original plan: - Paid all in cash without any investment in kind. - Assets intended as in-kind contributions will be transferred at market value in the future.) Payment completion date: April 2, 2018 Shareholders/Contribution Ratio: Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. 31%, Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. 31%, Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 38% 2. Outline of services No. of vessels in service/transport capacity: About 230 vessels / 1.44 million TEUs Service network: Total 85 services, calling at over 200 ports in 100 countries For details, please refer to the Ocean Network Service website: https://www.one-line.com/en Inquiries Inquiries can be directed to the following representatives: Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. Masaya Futakuchi, General Manager, Investor & Public Relations Group (TEL: +81-3- 3595-5189) Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. Kentaro Ayai, General Manager, Corporate Communication Division (TEL: +81-3- 3587-7015) Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha Ushio Koiso, General Manager, Corporate Communication Group (TEL: +81-3-3284-5058) This document includes information that constitutes "forward-looking statements" relating to the success and failure or the results of the integration of Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd., Mitsui O.S.K. -

Business Report and Financial Statements(302KB)

[Translation: Please note that the following purports to be an excerpt translation from the Japanese original Business Report and Financial Statements prepared for the convenience of shareholders outside Japan. However, in the case of any discrepancy between the translation and the Japanese original, the latter shall prevail.] BUSINESS REPORT (For the Period from April 1, 2013 through March 31, 2014) 1. Particulars Concerning the State of the Group (1) Business Developments [While overseas market prices fell for key metals the performance of Mitsubishi Materials Corporation (the Company) and Mitsubishi Materials Group (the Group) improved, thanks to impact from correction of yen appreciation and increased demand for cement as a result of full-scale demand generated by reconstruction efforts in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake.] During the fiscal year under review, the world economy on the whole headed toward recovery, as although there was a continuing slowdown in the economies of China, India, and other emerging nations, there were also signs of improvement such as a gradual change for the better in business conditions in the U.S. Conditions of the Japanese economy have gradually improved driven by an increase in public investment, and an increase in personal consumption driven by such factors as an improvement of the employment/income environment and a rush of demand before the consumption tax rate was raised. Regarding the operating environment for the Group, although overseas market prices fell for key metals, including copper, operations were affected overall by a correction in the exchange rate of the Japanese yen. Furthermore, earthquake disaster recovery projects reached a strong tempo and housing construction increased, leading firm demand for cement. -

Toyota, Nissan, Honda and Mitsubishi Agree to Joint Development of Charging Infrastructure for Phvs, Phevs and Evs in Japan

Toyota Motor Corporation Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. Honda Motor Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Motors Corporation Toyota, Nissan, Honda and Mitsubishi Agree to Joint Development of Charging Infrastructure for PHVs, PHEVs and EVs in Japan TOKYO, Japan (July 29, 2013) – Toyota Motor Corporation, Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., Honda Motor Co., Ltd., and Mitsubishi Motors Corporation jointly announced their agreement to work together to promote the installation of chargers for electric-powered vehicles (PHVs, PHEVs, EVs*) and build a charging network service that offers more convenience to drivers in Japan. The move is in recognition of the critical need to swiftly develop charging infrastructure facilities to promote the use of electric-powered vehicles. Assisted by subsidies provided by the Japanese government, the four automakers will bear part of the cost to install the charging facilities. They will also work together to build a convenient and accessible charging network in collaboration with companies that are already providing charging services in which each of the four automakers already have a financial stake. At present, there are about 1,700 quick chargers and just over 3,000* normal chargers in Japan, which is generally recognized to be insufficient. In addition, the lack of sufficient coordination among existing charging providers can be improved to offer better charging service to customers. The government announced subsidies for installation of charging facilities totaling 100.5 billion yen as part of its economic policy for fiscal year 2013 to quickly develop the charging infrastructure and expand the use of electric-powered vehicles using alternative energy sources. Currently, each prefecture in Japan is drawing up a vision for the use of the subsidies. -

TECHNICAL REPORT – PATENT ANALYSIS Enhancing Productivity in the Indian Paper and Pulp Sector

TECHNICAL REPORT – PATENT ANALYSIS Enhancing Productivity in the Indian Paper and Pulp Sector 2018 TABLE OF contEnts ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 10 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 1 INTRODUCTION 13 2 OVERVIEW OF THE PULP AND PAPER SECTOR 15 2.1. Status of the Indian Paper Industry 15 2.2. Overview of the Pulp and Papermaking Process 20 2.3. Patenting in the Paper and Pulp Industry: A Historical Perspective 22 2.4. Environmental Impact of the Pulp and Paper Industry 25 3 METHODOLOGY 27 3.1. Search Strategy 27 4 ANALYSIS OF PATENT DOCUMENTS USING GPI 31 4.1. Papermaking; Production of Cellulose (IPC or CPC class D21) 31 4.2. Analysis of Patenting Activity in Different Technology Areas using GPI 38 5 ANALYSIS OF THE INDIAN PATENT SCENARIO WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THIS REPORT 81 5.1. Analysis of Patents Filed in India 81 6 CONCLUDING REMARKS 91 REFERENCES 93 ANNEXURE 94 Annexure 1. Technologies related to paper manufacturing 94 Annexure 2. Sustainable/green technologies related to pulp and paper sector 119 Annexure 3. Emerging Technology Areas 127 List OF FIGURES Figure 2.1: Geographical Spread of Figure 4.11: (d) Applicant vs. Date of Indian Paper Mills .................................16 Priority Graph: Paper-Making Machines Figure 2.2: Share of Different Segments and Methods ........................................42 in Total Paper Production .......................19 Figure 4.11: (e) Applicant vs. Date of Figure 2.3: Variety Wise Production of Priority Graph: Calendars and Accessories ..43 Paper from Different Raw Materials ........19 Figure 4.11: (f) Applicant vs. Date of Figure 2.4: Different Varieties of Paper Priority Graph: Pulp or Paper Comprising Made from Various Raw Materials ..........19 Synthetic Cellulose or Non-Cellulose Fibres ..43 Figure 2.5: Diagram of a Process Block Figure 4.11: (g) Applicant vs. -

Stock Information and Notes for Shareholders

Stock Information and Notes for Shareholders Stock Information (As of September 30, 2018) Notes for Shareholders Fiscal year From April 1 to March 31 of the following year Number of Shares Issued 3,310,097,492 Ordinary General June Note: Model AA Class Shares are included. Shareholders’ Meeting Number of Shareholders 618,205 Dividend payout Year-end dividend: March 31 confirmation date Interim dividend: September 30 Stock listings Japan: Tokyo and Nagoya Ownership Breakdown Overseas: New York and London (thousands of shares) Transfer agent Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation Financial institutions Special account Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation 1,142,293 Individuals, etc. management institution (including treasury stock) 34.51% Contact 1-1, Nikko-cho, Fuchu-shi, Tokyo, Japan 793,786 Japan Toll-Free: (0120)232-711 23.98% Mailing address Shin-Tokyo Post Office, PO box No.29, Tokyo 137-8081 Japan Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation Corporate Agency Division Notice Other corporate Inquiries regarding change of registered address and requests entities Foreign corporate to purchase shares constituting less than one unit 679,787 entities and others (1) If you have an account with a securities company, please 20.54% 694,229 contact your securities company. 20.97% (2) If you do not have an account with a securities company Note: Ratio indicates the share of ownership to the total number of shares issued. and your shares are registered in special accounts, please contact Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation. Major Shareholders (Top 10) Ratio of the number of Number of shares held to Name shares held the total number of (thousands) shares issued (excluding T-ROAD treasury stock) (%) You are invited to visit the Japan Trustee Services Bank, Ltd. -

Notification of Settlement on the Projects Conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Notification of Settlement on the Projects Conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. in the Republic of South Africa and Recognition of Extraordinary Loss on Unconsolidated Basis and Other Expenses on Consolidated Basis Tokyo, December 18, 2019 --- Hitachi, Ltd. (TSE: 6501, “Hitachi”) today announced that Hitachi and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (“MHI”) have reached a settlement relating to a transfer of the boiler construction projects (the "Projects") in the Republic of South Africa conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. (“MHPS”), the joint venture company that integrated the respective thermal power generation system businesses of MHI and Hitachi, in conclusion of their discussion. 1. Circumstances of Settlement On March 31, 2016, Hitachi received from MHI a request for payments including part of amount to adjust business transfer price, etc. in connection with the project (collectively, the “Transfer Price Adjustment”)(1), and on January 31, 2017, MHI subsequently increased its claim amount for the Transfer Price Adjustment(2). On August 21, 2017, Hitachi received from the Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (the “JCAA”) the notice stating that MHI filed the request for arbitration with the JCAA on July 31, 2017 in order to claim for payment of 90,779 million ZAR (approximately 774.3 billion yen when converted at a rate of 8.53 yen to 1 ZAR) as the Transfer Price Adjustment(3). Hitachi and MHI have reached a settlement today as a result of discussion with sincerity and integrity in parallel with the arbitration. (1) “Ongoing Discussion on the projects of Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. in the Republic of South Africa” (announced on May 9, 2016) https://www.hitachi.com/New/cnews/month/2016/05/160509a.html (2) “Ongoing Discussion on the projects of Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. -

JOGMEC Assists Japanese Companies to Participate in the Wheatstone LNG Project in Western Australia

June 18, 2012 NEWS RELEASE www.jogmec.go.jp Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation Contact: Project Department TEL:03-6758-8218 Media Relations: Public Relation Division TEL:03-6758-8106 JOGMEC Assists Japanese Companies to Participate in the Wheatstone LNG Project in Western Australia JOGMEC (President: Hirobumi Kawano) announced today that it will provide equity financing and loan guarantee to the newly established Japanese vehicle to acquire a participating interest in the Wheatstone LNG Project, one of the largest resource projects in Australia, operated by Chevron Corporation. The foundation phase of the Wheatstone Project consists of two LNG processing trains with a combined capacity of 8.9 million tonnes per annum (MTPA), a domestic gas plant at Ashburton North in Western Australia, and associated offshore production facilities. The onshore foundation project is a joint venture between the Australian subsidiaries of Chevron (operator 72.14%), Apache (13%), Kuwait Foreign Petroleum Exploration Company (KUFPEC) (7%), Shell (6.4%) and Kyushu Electric (1.46%). The first two LNG trains will be supplied with gas from the Chevron-operated Wheatstone and Iago fields owned by Chevron (approx. 90%), Shell (8%) and Kyushu Electric (1.83%) as well as Julimar and Brunello fields of Apache and KUFPEC. First LNG is planned for 2016. PE Wheatstone Pty. Ltd. (PEW), a subsidiary of Pan Pacific Energy K.K. (PE), a Japanese corporation recently established by Mitsubishi Corporation, Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha and the Tokyo Electric Power Company, Incorporated (TEPCO), will acquire 8% interest in the onshore LNG facility and 10% in the Wheatstone and Iago fields from Chevron.