Comments Greenhouse Gas Emissions Program: Illustrative Scenarios and Program Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-4-2020 Draft Meeting Minutes Copy

TOWN OF EXETER SUSTAINABILITY ADVISORY COMMITTEE DRAFT MEETING MINUTES February 4, 2020 Meeting was called to order at 7:01 pm by Chetana Parmar. Members Present: Christopher Zigmont, Nina Braun, Chetana Parmar, Kristen Osterwood, Robin Tyner, Beverly Tappan and Niko Papakonstantis, Select Board Representative (Dave Sharples, Town Representative unable to attend) Philips Exeter Academy Student Representative: Liuxi Sun January Meeting Minutes: Public Comments Sam and Maggie from Philips Exeter that are in a class Human Population and Resource Consumption - have a course where they have a project to do and would like to do something with/for the Sustainability Committee - politically related would be great. Robin and Nina will follow up with ideas for them. Bob Kelly owns Seacoast farms compost product: has been primary supplier of compost blends for the seacoast for decades. Have been located in Fremont for most of those years. Landlord wanted to redevelop property so Bob is working with the town to operate out of the transfer station. Also be able to provide a distribution network - currently the town accepts leaves but does not necessarily create a high quality compost product. He plans to provide a yard of material for free for everyone who has a dump sticker. Also to save town money on operation of the town transfer station. Use a different a gate - off of Kingston Rd, to not increase traffic. - two people and two pieces of equipment (screener and front end loader) - Public private partnership with a memorandum of understanding - May require dump sticker to be able to drop off and pick up - To start soon, hopefully by March Sustainability Fair - Luixi Presented the goals and ideas of how to achieve those goals (attached to the end of the minutes) - Settle on a location and theme for submissions. -

CLIMATE CHANGE Take Meaningful Climate Change Action

CLIMATE CHANGE Take meaningful climate change action. Climate Change DEVELOP AND IMPLEMENT A CLIMATE ACTION PLAN Point of Contact: Andy Bertelsen / Nicole Antonopoulos Woodman Regional Plan Goal E&C.1. Proactively improve and maintain the region's air quality Goal E&C.2. Reduce greenhouse gas emissions Goal E&C.3. Strengthen community and natural environmental resiliency through climate adaptation efforts. Goal E&C.4. Integrate available science into policies governing the use and conservation of Flagstaff's natural resources. Goal T.3 Provide transportation infrastructure that is conducive to conservation, preservation, and development goals to avoid, minimize, or mitigate impacts on the natural and build environment Goal E.1. Increase energy efficiency Goal E.2. Expand production and use of renewable energy POLICY IMPLICATION Healthy forests, prepared for and resilient to change from environmental factors, including Climate Change, is fostered by: Application of the City's Forest Stewardship Plan and the Greater Flagstaff Community Wildfire Protection Plan (adopted by Council in 2005), Implementation of on-going forest treatment efforts and the Flagstaff Watershed Protection Plan (passed by voters in 2012), and Support of multi-party collaborative efforts (ex: Greater Flagstaff Forests Partnership [GFFP] and Four Forest Restoration Initiative [4FRI]) and the National Wildfire Cohesive Strategy Ongoing support for initiatives identified in the climate action plan. Fiscal implications will be identified during the FY 19 budget -

SUSTAINABILITY COMMITTEE AGENDA, SUMMARY and GOALS June 7, 2017

BEMIDJI SUSTAINABILITY COMMITTEE AGENDA, SUMMARY AND GOALS June 7, 2017 Present Anna Carlson, Jordan Lutz, Nicole Deziel, Diana Kuklinski, Mike Ruffenach, Michael Meehlhause, Brad Kingery, Matthew Rogotzke, Matthew Liedke (Pioneer), Jesse Robertson, Naomi Carlson GREENSTEP CITIES Description Minnesota GreenStep Cities is a voluntary challenge, assistance and recognition program to help cities achieve their sustainability and quality-of-life goals. This free continuous improvement program, managed by a public-private partnership, is based upon 29 best practices. Each best practice can be implemented by completing one or more actions at a 1, 2 or 3-star level, from a list of four to eight actions. These actions are tailored to all Minnesota cities, focus on cost savings and energy use reduction, and encourage civic innovation. The 28 best practices are under five categories, including: (1) Buildings and Lighting; (2) Land Use; (3) Transportation; (4), Environmental Management; and (5) Economic and Community Development. Action Items Sustainable City Award – The City of Bemidji will be applying again for the Sustainable City Award. GreenCorp Member – The City was awarded a GreenCorp member for the 2016-2017 season. Nicole Deziel started in September and is working on a tree inventory and tree standards policy. Step 4 Recognition – The GreenStep Cities program has added a Step 4 which focuses on metrics and tracking. A future Step 5 is being developed which would show the improvements within the metrics. Bemidji participated in Regional Indicators Initiation which could help Bemidji in reaching Step 4 recognition. Hunter Edberg completed his internship regarding entering data for Step 4. Reporting – We currently do not have a GreenStep Cities Volunteer Coordinator. -

Oreo Parable for Climate Change

Who am I to talk about climate change? My name is Phil Beauchamp. I graduated from the University of California at San Diego, in 1971, with a bachelor’s degree in Chemistry. I entered the United States Army in 1971 and served for 3 years. After the Army I attended Cal Poly Pomona, graduating in 1977 with a master’s degree in chemistry. I then attended University of California at Irvine, where I obtained my Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 1981. That same year I obtained a tenure track professor position at Cal Poly Pomona, where I taught chemistry for 31 years, officially retiring in 2012. While at Cal Poly, I was in charge of the Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) instrument for about 25 years (NMR is similar to MRI used in medicine). NMR uses the radiowave region of the electromagnetic spectrum to study the structure of organic and biological molecules. The electromagnetic spectrum divides energy waves according to energy (x-rays > ultraviolet (UV) > visible > infrared (IR) > microwaves ( ) > radiowaves). Three of these, UV, visible and IR, are often included in discussions about Climate Change. Throughout my college career my main research focus was on determining the chemical structure of natural compounds isolated from plants by my colleague, Vasu Dev, using spectroscopy (NMR, IR and MS). Even though retired, I still continue to teach organic chemistry at Cal Poly half time, and I have 2 courses in the fall 2019 semester with 230 students. About 4 years ago I read my first book on climate change (CC) and immediately became concerned about this subject. -

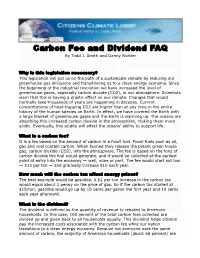

Carbon Fee and Dividend FAQ by Todd J

Carbon Fee and Dividend FAQ By Todd J. Smith and Danny Richter Why is this legislation necessary? This legislation will put us on the path of a sustainable climate by reducing our greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning us to a clean energy economy. Since the beginning of the industrial revolution we have increased the level of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2), in our atmosphere. Scientists warn that this is having a drastic effect on our climate. Changes that would normally take thousands of years are happening in decades. Current concentrations of heat-trapping CO2 are higher than at any time in the entire history of the human species on Earth. In effect, we have covered the Earth with a large blanket of greenhouse gases and the Earth is warming up. The oceans are absorbing this increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, making them more acidic. Eventually, this acidity will affect the oceans’ ability to support life. What is a carbon fee? It is a fee based on the amount of carbon in a fossil fuel. Fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal contain carbon. When burned they release the potent green house gas, carbon dioxide (CO2), into the atmosphere. The fee is based on the tons of carbon dioxide the fuel would generate, and it would be collected at the earliest point of entry into the economy — well, mine or port. The fee would start out low — $15 per ton — and gradually increase $10 each year. How much will the carbon tax affect energy prices? The best example would be gasoline. -

York and Bell-Energy Transition Or Addition.Pdf

Energy Research & Social Science 51 (2019) 40–43 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy Research & Social Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/erss Perspective Energy transitions or additions? Why a transition from fossil fuels requires more than the growth of T renewable energy ⁎ Richard Yorka, , Shannon Elizabeth Bellb a Department of Sociology and Environmental Studies Program, 1291 University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1291, USA b Department of Sociology, Virginia Tech, 225 Stanger Street, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Is an energy transition currently in progress, where renewable energy sources are replacing fossil fuels? Previous Energy transition changes in the proportion of energy produced by various sources – such as in the nineteenth century when coal Biofuels surpassed biomass in providing the largest share of the global energy supply and in the twentieth century when Coal petroleum overtook coal – could more accurately be characterized as energy additions rather than transitions. In Renewables both cases, the use of the older energy source continued to grow, despite rapid growth in the new source. Evidence from contemporary trends in energy production likewise suggest that as renewable energy sources compose a larger share of overall energy production, they are not replacing fossil fuels but are rather expanding the overall amount of energy that is produced. We argue that although it is reasonable to expect that renewables will come to provide a growing share of the global energy supply, it is misleading to characterize this growth in renewable energy as a “transition” and that doing so could inhibit the implementation of meaningful policies aimed at reducing fossil fuel use. -

Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: the Case of Germany and Poland

climate Article Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland Zbigniew Bohdanowicz Economic Sciences, University of Warsaw, 00-241 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected]; Tel.: +48-668-862-414 Abstract: There are numerous studies assessing the influence of individual sociological, political, and demographic factors on attitudes towards climate change. However, there is still a need for a deeper understanding of the reasons behind these attitudes and for research based on results from more than one country. This study empirically examines a range of psychosocial and demographic determinants of support for climate policy (renewable energy, energy efficiency and carbon tax) in Germany and Poland (n = 1969). The results show that the societies of both countries, despite significant differences in income, culture and political stance on climate change, similarly support implementation of climate policies. For both countries valid predictors of support are: awareness, emotional response to climate crisis, sense of control, and belief in effectiveness of solutions; the study also shows predictors relevant in only one country. Factor analysis identified similar dimensions of attitudes toward climate change in both countries. The main findings show that support for climate policy is high in both countries and that the public is ready to accept more ambitious climate goals. Despite the differences between the countries, a coherent climate policy seems justified. The study also shows differences between the countries and provides recommendations for policymakers. Keywords: climate change; renewable energy; carbon tax; energy efficiency; public support; climate policy Citation: Bohdanowicz, Z. Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland. -

Download PDF File Draft Climate Emergency Comments

Comments Organization (optional) Mayor Wheeler and City Council Members,Thank you for taking public testimony on the draft climate emergency declaration. I have reviewed it and have a few pieces of feedback to share:(1) The City of Portland’s climate response would benefit from more input and accountability than exists today. As reviewer and recommending body for the Climate Action Plan, the Planning and Sustainability Commission theoretically offers this. But the PSC has not provided substantive accountability for the sustainability side of the city’s operations since the passage of the 2015 Climate Action Plan, and the climate crisis can’t wait.The City should convene and empower a new Climate Commission to fill this role. This could be the ‘new governance structure’ referenced in the draft declaration – but it should have more authority and include a broader coalition of members. In addition to (and ideally overlapping with) members of frontline communities and youth leaders, the commission should include technical and policy experts familiar with climate science, energy policy, and levers of change. Frontline communities and youth members must be at the decision-making table to ensure the city adopts just climate policies. But they need not bear the full responsibility of climate leadership. This is a huge undertaking that demands as much leadership as we can muster – inclusive of but not limited to young people and frontline communities.(2) The plan should be specific and action-oriented, with clear timelines. The current draft should be updated to include specific action items with deadlines. At minimum, it should direct all bureaus to report back within 90 days on opportunities for radical greenhouse gas and co-pollutant emissions reductions and greenhouse gas drawdown opportunities, including metrics that prioritize the decrease of fossil fuel use and climate-adaptive land use planning. -

Oxford Handbooks Online

Environment and Development Challenges Oxford Handbooks Online Environment and Development Challenges: The Imperative of a Carbon Fee and Dividend James E. Hansen The Oxford Handbook of the Macroeconomics of Global Warming Edited by Lucas Bernard and Willi Semmler Print Publication Date: Jan 2015 Subject: Economics and Finance, Environmental, Agricultural, and Natural Resources Economics, Public Economics and Policy Online Publication Date: May DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199856978.013.0026 2015 Abstract and Keywords This chapter discusses the importance of a carbon fee and dividend in minimizing the impacts of climate change on humanity and nature. Before outlining the policies needed to produce a rapid phase-out of fossil fuel emissions, it enumerates the fundamental flaws of the Kyoto Protocol from the standpoint of climate science. One flaw is the “cap” mechanism, which purports to reduce carbon emissions at the rate required to stabilize climate but fails to provide universal price signals that would reward efforts to reduce emissions. Another flaw concerns “offsets” that allow nations to limit reduction of fossil fuel emissions. This chapter argues that the Kyoto Protocol’s cap-and-trade- with-offsets approach must be abandoned and replaced with an approach that phases out fossil fuels in an economically efficient manner, such as utilizing carbon-free energy sources like renewable energy and nuclear power. Specifically, it proposes a flat (across-the-board) rising fee (tax) on carbon emissions. It also explains how such an approach may be implemented both nationally and internationally. Keywords: cap mechanism, carbon dividend, carbon emissions, carbon fee, climate change, fossil fuel emissions, fossil fuels, Kyoto Protocol, offsets, renewable energy MOST governments have paid little attention to the threat of human-made climate change. -

PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO ECOSYSTEM DECLINE in VICTORIA the Environment and Planning Committee

LC EPC Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria Submission 903 PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO ECOSYSTEM DECLINE IN VICTORIA The Environment and Planning Committee Submission by Andreas Bimba (Rev A) Dear Members of the Committee, I would like to present my submission as a concerned member of the public to the Victorian Parliament’s Inquiry into Ecosystem Decline. The initial part is my own individual statement which is followed by my general statement which was prepared by the Victorian Greens and supporters, and which I have carefully read, aligns with my own values and understandings and together these comprise my submission to this Inquiry. INDIVIDUAL STATEMENT I am claiming that a practical and achievable path for the Victorian Government to meet it's proportional share of the global obligation to adequately meet the global warming crisis and the more general obligation to protect the natural environment in Victoria and to repair and extend that natural environment in an appropriate way, is substantially known and all that is currently lacking is the appropriate political mandate and community consensus to follow such a necessary path. I firstly go into some depth to explain the seriousness and urgency of the global warming crisis and the trajectories that should be followed to mitigate the expected adverse effects. Quotes from credible references are used to build the case for a fast trajectory of emission reductions and the concurrent removal of excessive CO2 from the atmosphere. Global warming if not addressed adequately will dwarf all other environmental concerns and Victoria must play at least its proportionate part in meeting this challenge. -

The Long View

Winter 2014 Oregon State Bar Sustainable Future Section The Long View Also IN THIS ISSUE: A Revenue Neutral Crowdfunding for Carbon Tax: Good for the Economy, the Climate, Small Oregon Businesses: and the Psyche By Daniela Brod Proposed New Rules By Jeffrey S. Cronn and Claire E. Brown SECTION NEWS: Editor’s Note: One segment of the sustainability movement calls for The OSB Sustainable shifting investments from global capital markets to a more localized econ- Future Section: omy, which is extraordinarily difficult to do for most investors. This arti- A Five Year Report cle describes one approach to facilitate investments in local businesses. By Dick Roy You Say "Crowdfunding," Securities Lawyers Say… New Partners in Although the term "crowdfunding" is used to describe a range of fundraising Sustainability strategies, it is primarily associated with raising relatively small amounts of money from a wide group of people, usually by way of the internet. Sites such as Steven R. Schell Kickstarter and indiegogo have made non-equity crowdfunding a popular way of Receives the President’s raising money for a cause, including launching a for-profit company. Typically, Sustainability Award companies using these sites allow "backers" to either pre-purchase products or make a donation in exchange for a token gift. Bodyfelt Mount LLP: Recipient of the 2014 Fundraising involving general solicitation for equity investments raised exclu- Sustainable Law Office sively from accredited investors in what is otherwise a traditional private place- Leadership Award ment of securities is often referred to as "accredited crowdfunding." Many com- mentators and groups have agitated for a crowdfunding option that would merge these two, allowing for equity crowdfunding without regard to an individual's BOOK REVIEW: wealth or sophistication, tapping into the enthusiasm and energy of a crowd as well as its funds. -

An Analysis of the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act of 2019

AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENERGY INNOVATION AND CARBON DIVIDEND ACT OF 2019 by Michael Joseph Shaheen A capstone submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Management Baltimore, Maryland April 2020 © 2020 Michael Shaheen All Rights Reserved Abstract The United States and the rest of the world need to make drastic policy changes to address the increasing amount of carbon emissions that is escalating the climate change crisis. In recent years, climate change has cemented itself as a platform issue among Democratic candidates and lawmakers. The Green New Deal, proposed by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez [D-NY-14] and Senator Edward Markey [D- MA], has galvanized discussions on ways to counteract climate change. While that may be the most popular climate change policy in the media, a bipartisan solution may potentially be a better fit to mitigate the climate crisis. On January 24, 2019, Representative Ted E. Deutch [D-FL-22] introduced the H.R.763 – Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act of 2019. The Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act (EICDA) of 2019 is a carbon tax that will impose a fee across all levels of the United States on fossil fuels such as natural gas, coal, oil, and on other imports and producers. This independent analysis of the EICDA will evaluate its main goal to reduce carbon emissions substantially by 2030 and practically eliminate emissions by 2050. As discussed in this capstone, the EICDA may lead to an ample decrease in emissions, generation of revenue, creation of jobs, and a transformed green economy.