Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: the Case of Germany and Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-4-2020 Draft Meeting Minutes Copy

TOWN OF EXETER SUSTAINABILITY ADVISORY COMMITTEE DRAFT MEETING MINUTES February 4, 2020 Meeting was called to order at 7:01 pm by Chetana Parmar. Members Present: Christopher Zigmont, Nina Braun, Chetana Parmar, Kristen Osterwood, Robin Tyner, Beverly Tappan and Niko Papakonstantis, Select Board Representative (Dave Sharples, Town Representative unable to attend) Philips Exeter Academy Student Representative: Liuxi Sun January Meeting Minutes: Public Comments Sam and Maggie from Philips Exeter that are in a class Human Population and Resource Consumption - have a course where they have a project to do and would like to do something with/for the Sustainability Committee - politically related would be great. Robin and Nina will follow up with ideas for them. Bob Kelly owns Seacoast farms compost product: has been primary supplier of compost blends for the seacoast for decades. Have been located in Fremont for most of those years. Landlord wanted to redevelop property so Bob is working with the town to operate out of the transfer station. Also be able to provide a distribution network - currently the town accepts leaves but does not necessarily create a high quality compost product. He plans to provide a yard of material for free for everyone who has a dump sticker. Also to save town money on operation of the town transfer station. Use a different a gate - off of Kingston Rd, to not increase traffic. - two people and two pieces of equipment (screener and front end loader) - Public private partnership with a memorandum of understanding - May require dump sticker to be able to drop off and pick up - To start soon, hopefully by March Sustainability Fair - Luixi Presented the goals and ideas of how to achieve those goals (attached to the end of the minutes) - Settle on a location and theme for submissions. -

CLIMATE CHANGE Take Meaningful Climate Change Action

CLIMATE CHANGE Take meaningful climate change action. Climate Change DEVELOP AND IMPLEMENT A CLIMATE ACTION PLAN Point of Contact: Andy Bertelsen / Nicole Antonopoulos Woodman Regional Plan Goal E&C.1. Proactively improve and maintain the region's air quality Goal E&C.2. Reduce greenhouse gas emissions Goal E&C.3. Strengthen community and natural environmental resiliency through climate adaptation efforts. Goal E&C.4. Integrate available science into policies governing the use and conservation of Flagstaff's natural resources. Goal T.3 Provide transportation infrastructure that is conducive to conservation, preservation, and development goals to avoid, minimize, or mitigate impacts on the natural and build environment Goal E.1. Increase energy efficiency Goal E.2. Expand production and use of renewable energy POLICY IMPLICATION Healthy forests, prepared for and resilient to change from environmental factors, including Climate Change, is fostered by: Application of the City's Forest Stewardship Plan and the Greater Flagstaff Community Wildfire Protection Plan (adopted by Council in 2005), Implementation of on-going forest treatment efforts and the Flagstaff Watershed Protection Plan (passed by voters in 2012), and Support of multi-party collaborative efforts (ex: Greater Flagstaff Forests Partnership [GFFP] and Four Forest Restoration Initiative [4FRI]) and the National Wildfire Cohesive Strategy Ongoing support for initiatives identified in the climate action plan. Fiscal implications will be identified during the FY 19 budget -

Phase-Out 2020: Monitoring Europe's Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Phase-out 2020 Monitoring Europe’s fossil fuel subsidies Ipek Gençsü, Maeve McLynn, Matthias Runkel, Markus Trilling, Laurie van der Burg, Leah Worrall, Shelagh Whitley, and Florian Zerzawy September 2017 Report partners ODI is the UK’s leading independent think tank on international development and humanitarian issues. Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe is Europe’s largest coalition working on climate and energy issues. Readers are encouraged to reproduce material for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holders, ODI and Overseas Development Institute CAN Europe request due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For 203 Blackfriars Road CAN Europe online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. London SE1 8NJ Rue d’Edimbourg 26 The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not Tel +44 (0)20 7922 0300 1050 Brussels, Belgium necessarily represent the views of ODI or our partners. Fax +44 (0)20 7922 0399 Tel: +32 (0) 28944670 www.odi.org www.caneurope.org © Overseas Development Institute and CAN Europe 2017. This work is licensed [email protected] [email protected] under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: Oil refinery in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany – Ralf Vetterle (CC0 creative commons license). 2 Report Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for support and advice on the report from: Dave Jones of Sandbag UK, Colin Roche of Friends of the Earth Europe, Andrew Scott and Sejal Patel of the Overseas Development Institute, Helena Wright of E3G, and Andrew Murphy of Transport & Environment, and Alex Doukas of Oil Change International. -

A New Era for Wind Power in the United States

Chapter 3 Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States 1 Photo from iStock 7943575 1 This page is intentionally left blank 3 Impacts of the Wind Vision Summary Chapter 3 of the Wind Vision identifies and quantifies an array of impacts associated with continued deployment of wind energy. This 3 | Summary Chapter chapter provides a detailed accounting of the methods applied and results from this work. Costs, benefits, and other impacts are assessed for a future scenario that is consistent with economic modeling outcomes detailed in Chapter 1 of the Wind Vision, as well as exist- ing industry construction and manufacturing capacity, and past research. Impacts reported here are intended to facilitate informed discus- sions of the broad-based value of wind energy as part of the nation’s electricity future. The primary tool used to evaluate impacts is the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL’s) Regional Energy Deployment System (ReEDS) model. ReEDS is a capacity expan- sion model that simulates the construction and operation of generation and transmission capacity to meet electricity demand. In addition to the ReEDS model, other methods are applied to analyze and quantify additional impacts. Modeling analysis is focused on the Wind Vision Study Scenario (referred to as the Study Scenario) and the Baseline Scenario. The Study Scenario is defined as wind penetration, as a share of annual end-use electricity demand, of 10% by 2020, 20% by 2030, and 35% by 2050. In contrast, the Baseline Scenario holds the installed capacity of wind constant at levels observed through year-end 2013. -

Hydroelectric Power -- What Is It? It=S a Form of Energy … a Renewable Resource

INTRODUCTION Hydroelectric Power -- what is it? It=s a form of energy … a renewable resource. Hydropower provides about 96 percent of the renewable energy in the United States. Other renewable resources include geothermal, wave power, tidal power, wind power, and solar power. Hydroelectric powerplants do not use up resources to create electricity nor do they pollute the air, land, or water, as other powerplants may. Hydroelectric power has played an important part in the development of this Nation's electric power industry. Both small and large hydroelectric power developments were instrumental in the early expansion of the electric power industry. Hydroelectric power comes from flowing water … winter and spring runoff from mountain streams and clear lakes. Water, when it is falling by the force of gravity, can be used to turn turbines and generators that produce electricity. Hydroelectric power is important to our Nation. Growing populations and modern technologies require vast amounts of electricity for creating, building, and expanding. In the 1920's, hydroelectric plants supplied as much as 40 percent of the electric energy produced. Although the amount of energy produced by this means has steadily increased, the amount produced by other types of powerplants has increased at a faster rate and hydroelectric power presently supplies about 10 percent of the electrical generating capacity of the United States. Hydropower is an essential contributor in the national power grid because of its ability to respond quickly to rapidly varying loads or system disturbances, which base load plants with steam systems powered by combustion or nuclear processes cannot accommodate. Reclamation=s 58 powerplants throughout the Western United States produce an average of 42 billion kWh (kilowatt-hours) per year, enough to meet the residential needs of more than 14 million people. -

Are Biofuels an Effective and Viable Energy Strategy for Industrialized Societies? a Reasoned Overview of Potentials and Limits

Sustainability 2015, 7, 8491-8521; doi:10.3390/su7078491 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Are Biofuels an Effective and Viable Energy Strategy for Industrialized Societies? A Reasoned Overview of Potentials and Limits Tiziano Gomiero Independent Consultant and Researcher on Multi-Criteria Farming and Food System Analysis, Agro-Energies, Environmental Issues, Treviso 30121, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-32-0464-3496 Academic Editor: Andrew Kusiak Received: 7 April 2015 / Accepted: 26 June 2015 / Published: 30 June 2015 Abstract: In this paper, I analyze the constraints that limit biomass from becoming an alternative, sustainable and efficient energy source, at least in relation to the current metabolism of developed countries. In order to be termed sustainable, the use of an energy source should be technically feasible, economically affordable and environmentally and socially viable, considering society as a whole. Above all, it should meet society’s “metabolic needs,” a fundamental issue that is overlooked in the mainstream biofuels narrative. The EROI (Energy Return on Investment) of biofuels reaches a few units, while the EROI of fossil fuels is 20–30 or higher and has a power density (W/m2) thousands of times higher than the best biofuels, such as sugarcane in Brazil. When metabolic approaches are used it becomes clear that biomass cannot represent an energy carrier able to meet the metabolism of industrialized societies. For our industrial society to rely on “sustainable biofuels” for an important fraction of its energy, most of the agricultural and non-agricultural land would need to be used for crops, and at the same time a radical cut to our pattern of energy consumption would need to be implemented, whilst also achieving a significant population reduction. -

Update on Recent Progress in Reform of Inefficient Fossil-Fuel Subsidies That Encourage Wasteful Consumption

UPDATE ON RECENT PROGRESS IN REFORM OF INEFFICIENT FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES THAT ENCOURAGE WASTEFUL CONSUMPTION Contribution by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to the G20 Energy Transitions Working Group in consultation with: International Energy Forum (IEF), Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the World Bank 2nd Energy Transitions Working Group Meeting Toyama, 18-19 April 2019 Update on Recent Progress in Reform of Inefficient Fossil-Fuel Subsidies that Encourage Wasteful Consumption This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. This update does not necessarily express the views of the G20 countries or of the IEA, IEF, OECD, OPEC and the World Bank or their member countries. The G20 countries, IEA, IEF, OECD, OPEC and the World Bank assume no liability or responsibility whatsoever for the use of data or analyses contained in this document, and nothing herein shall be construed as interpreting or modifying any legal obligations under any intergovernmental agreement, treaty, law or other text, or as expressing any legal opinion or as having probative legal value in any proceeding. Please cite this publication as: OECD/IEA (2019), "Update on recent progress in reform of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption", https://oecd.org/fossil-fuels/publication/OECD-IEA-G20-Fossil-Fuel-Subsidies-Reform-Update-2019.pdf │ 3 Summary This report discusses recent trends and developments in the reform of inefficient fossil- fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption, within the G20 and beyond. -

On Alternative Energy Hydroelectric Power

Focus On Alternative Energy Hydroelectric Power What is Hydroelectric Power (Hydropower)? Hydroelectric power comes from the natural flow of water. The energy is produced by the fall of water turning the blades of a turbine. The turbine is connected to a generator that converts the energy into electricity. The amount of electricity a system can produce depends on the quantity of water passing through a turbine (the volume of water flow) and the height from which the water ‘falls’ (head). The greater the flow and the head, the more electricity produced. Why Wind? Hydropower is a clean, domestic, and renewable source of energy. It provides inexpensive electricity and produces no pollution. Unlike fossil fuels, hydropower does not destroy water during the production of electricity. Hydropower is the only renewable source of energy that can replace fossil fuels’ electricity production while satisfying growing energy needs. Hydroelectric systems vary in size and application. Micro-hydroelectric plants are the smallest types of hydroelectric systems. They can generate between 1 kW and 1 MW of power and are ideal for powering smaller services such as processing machines, small farms, and communities. Large hydroelectric systems can produce large amounts of electricity. These systems can be used to power large communities and cities. Why Hydropower? Technical Feasibility Hydropower is the most energy efficient power generator. Currently, hydropower is capable of converting 90% of the available energy into electricity. This can be compared to the most efficient fossil fuel plants, which are only 60% efficient. The principal advantages of using hydropower are its large renewable domestic resource base, the absence of polluting emissions during operation, its capability in some cases to respond quickly to utility load demands, and its very low operating costs. -

Fossil Fuels and Water Quality 75

Chapter 4 Lucy Allen, Michael J. Cohen, David Abelson, and Bart Miller Fossil fuels are essential to the global economy—for electricity production, transporta- tion, plastics and chemicals manufacturing, heating, and many other purposes. How- ever,Fossil the extraction Fuels and processing and of fossil Water fuels, in addition Quality to their use, have profound impacts on the environment and natural resources, including water. Large oil spills— such as the recent Deepwater Horizon drilling rig spill, which leaked over 4.9 million barrels (780,000 cubic meters) of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico—have focused atten- tion on the potential for disasters associated with oil drilling to cause contamination of the natural environment (Lubchenco et al. 2010). The growing recognition of the seri- ous risks to surface-water and groundwater quality from natural gas fracking operations also raises new questions. And even normal fossil-fuel extraction and refining processes pollute the environment. The connections between water and energy have been studied in recent years, with growing recognition of how closely the two are linked. Water is used, in varying quanti- ties and ways, in every step of fossil-fuel extraction and processing (Ptacek et al. 2004). For example, the amount of coal produced worldwide in 2009 required an estimated 1.3 to 4.5 billion cubic meters (m3) of water for extraction and processing.1 Oil refining requires approximately 4 to 8 million m3 of water daily in the United States alone (the amount of water that two to three million U.S. households use daily) (US DOE 2006). -

SUSTAINABILITY COMMITTEE AGENDA, SUMMARY and GOALS June 7, 2017

BEMIDJI SUSTAINABILITY COMMITTEE AGENDA, SUMMARY AND GOALS June 7, 2017 Present Anna Carlson, Jordan Lutz, Nicole Deziel, Diana Kuklinski, Mike Ruffenach, Michael Meehlhause, Brad Kingery, Matthew Rogotzke, Matthew Liedke (Pioneer), Jesse Robertson, Naomi Carlson GREENSTEP CITIES Description Minnesota GreenStep Cities is a voluntary challenge, assistance and recognition program to help cities achieve their sustainability and quality-of-life goals. This free continuous improvement program, managed by a public-private partnership, is based upon 29 best practices. Each best practice can be implemented by completing one or more actions at a 1, 2 or 3-star level, from a list of four to eight actions. These actions are tailored to all Minnesota cities, focus on cost savings and energy use reduction, and encourage civic innovation. The 28 best practices are under five categories, including: (1) Buildings and Lighting; (2) Land Use; (3) Transportation; (4), Environmental Management; and (5) Economic and Community Development. Action Items Sustainable City Award – The City of Bemidji will be applying again for the Sustainable City Award. GreenCorp Member – The City was awarded a GreenCorp member for the 2016-2017 season. Nicole Deziel started in September and is working on a tree inventory and tree standards policy. Step 4 Recognition – The GreenStep Cities program has added a Step 4 which focuses on metrics and tracking. A future Step 5 is being developed which would show the improvements within the metrics. Bemidji participated in Regional Indicators Initiation which could help Bemidji in reaching Step 4 recognition. Hunter Edberg completed his internship regarding entering data for Step 4. Reporting – We currently do not have a GreenStep Cities Volunteer Coordinator. -

Fossil Fuel Hunt Adapted from “Fossil Fuels and the Ticking Clock” At

Issue 7: Energy and the Polar Environment http://beyondpenguins.nsdl.org/ Fossil Fuel Hunt adapted from “Fossil Fuels and the Ticking Clock” at www.powerhousekids.com You’ve been hired by an energy company to find coal deposits. The coal you find will be burned to produce electricity for homes and businesses. Coal and natural gas are known as fossil fuels. They are formed from the remains of ancient plants and animals. When the plants and animals died and became buried deep in the earth, the heat and pressure of the earth’s layers slowly transformed them into coal, natural gas, and oil. In this activity, you will search for pennies four times. You only have 30 seconds to search each time! After each search, you will count the pennies, record the total, and deposit them in the correctly numbered cup. After the fourth search, you will recount each cup of pennies one at a time, and make a bar graph to show the number of pennies you found in each search. First search: __________ Second search: ____________ Third search: ___________ Fourth search: __________ Copyright 2008: Ohio State University. Funded by the National Science Foundation. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. Issue 7: Energy and the Polar Environment http://beyondpenguins.nsdl.org/ 45 35 Number of pennies found 25 15 5 1st 2nd 3rd 4th search search search search Questions: 1. In which search did you find the most pennies? 2. In which search did you find the least pennies? 3. Why do you think it became increasingly harder to find pennies? 4. -

Fossil Fuels? Beside Each Sentence Below, Write Down Whether It Is Talking About Coal, Oil, Or Natural Gas

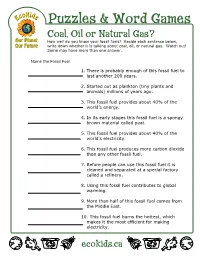

Puzzles & Word Games Coal, Oil or Natural Gas? How well do you know your fossil fuels? Beside each sentence below, write down whether it is talking about coal, oil, or natural gas. Watch out! Some may have more than one answer. Name the Fossil Fuel 1. There is probably enough of this fossil fuel to last another 200 years. 2. Started out as plankton (tiny plants and animals) millions of years ago. 3. This fossil fuel provides about 40% of the world’s energy. 4. In its early stages this fossil fuel is a spongy brown material called peat. 5. This fossil fuel provides about 40% of the world's electricity. 6. This fossil fuel produces more carbon dioxide than any other fossil fuel. 7. Before people can use this fossil fuel it is cleaned and separated at a special factory called a refinery. 8. Using this fossil fuel contributes to global warming. 9. More than half of this fossil fuel comes from the Middle East. 10. This fossil fuel burns the hottest, which makes it the most efficient for making electricity. ecokids.ca Puzzles & Word Games Coal, Oil or Natural Gas? How well do you know your fossil fuels? Beside each sentence below, write down whether it is talking about coal, oil, or natural gas. Watch out! Some may have more than one answer. Name the Fossil Fuel Coal 1. There is probably enough of this fossil fuel to last another 200 years. Oil & Natural gas 2. Started out as plankton (tiny plants and animals) millions of years ago.