Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAME of THRONES® the Follow Tours Include Guides with Special Interest and a Passion for the Game of Thrones

GAME OF THRONES® The follow tours include guides with special interest and a passion for the Game of Thrones. However you can follow the route to explore the places featured in the series. Meet your Game of Thrones Tours Guide Adrian has been a tour guide for many years, with a passion for Game of Thrones®. During filming he was an extra in various scenes throughout the series, most noticeably, a stand in double for Ser Davos. He is also clearly seen guarding Littlefinger before his final demise at the hands of the Stark sisters in Winterfell. Adrian will be able to bring his passion alive through his experience, as well as his love of Northern Ireland. Cairncastle ~ The Neck & North of Winterfell 1 Photo stop of where Sansa learns of her marriage to Ramsay Bolton, and also where Ned beheads Will, the Night’s Watch deserter. Cairncastle Refreshment stop at Ballygally Castle, Ballygally Located on the scenic Antrim coast facing the soft, sandy beaches of Ballygally Bay. The Castle dates back to 1625 and is unique in that it is the only 17th Century building still used as a residence in Northern Ireland today. The hotel is reputedly haunted by a friendly ghost and brave guests can visit the ‘ghost room’ in one of the towers to see for themselves. View Door No. 9 of the Doors of Thrones and collect your first stamp in your Journey of Doors passport! In the hotel foyer you will be able to admire the display cabinets of the amazing Steensons Game of Thrones® inspired jewellery. -

Mhysa Or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in a Song of Ice and Fire

Mhysa or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in A Song of Ice and Fire by Rachel Hartnett A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Rachel Hartnett ii Acknowledgements Foremost, I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Swanstrom for her motivation, support, and knowledge. Besides encouraging me to pursue graduate school, she has been a pillar of support both intellectually and emotionally throughout all of my studies. I could never fully express my appreciation, but I owe her my eternal gratitude and couldn’t have asked for a better advisor and mentor. I also would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Eric Berlatsky and Dr. Carol McGuirk, for their inspiration, insightful comments, and willingness to edit my work. I also thank all of my fellow English graduate students at FAU, but in particular: Jenn Murray and Advitiya Sachdev, for the motivating discussions, the all-nighters before paper deadlines, and all the fun we have had in these few years. I’m also sincerely grateful for my long-time personal friends, Courtney McArthur and Phyllis Klarmann, who put up with my rants, listened to sections of my thesis over and over again, and helped me survive through the entire process. Their emotional support and mental care helped me stay focused on my graduate study despite numerous setbacks. Last but not the least, I would like to express my heart-felt gratitude to my sisters, Kelly and Jamie, and my mother. -

GAME of THRONES Committee

2013 ALBERT CAMPBELL COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE MODEL UNITED NATIONS PRESENTS… GAME OF THRONES Committee Lead Chair: Ravena Rasalingam Chairs: Bharvjit Parmar and Adeel Malik Introduction Welcome delegates to the 2013 ACCI Model United Nations conference! Your head chairs for this committee will be Ravena Rasalingam and Bharvjit Parmar. This committee will be based on the book series, “A Song of Ice and Fire” and the HBO show, “Game of Thrones”. Disclaimer: Albert Campbell nor the chairs of this committee claim the proceeding as our original content; everything was invented by George R. R. Martin in his fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire. In this committee, the topics discussed will include the use of magic, sorcery, and the aid of supernatural creatures during wartime, the crisis involving the White Walkers, and the current economic state of Westeros. But be advised, this is a crisis committee. Please try to act in character and feel free to act in your own best interest. Plotting, scheming and clever use of personal relationships are encouraged! This council’s goals are to maintain peace and stability in Westeros, and to ensure the interests of the King. Good luck delegates, and remember- when you play the game of thrones, you either win or die. History: The Dawn Age (Prehistory- 1000) Westeros was initially inhabited by the Children of the Forest (a mysterious race of human-like creatures), giants and other mystical beings. The First men invaded Westeros in 1200 bringing weapons and bronze. The First men had larger numbers, were stronger, bigger, and more technologically advanced than the Children of the Forest and eventually established hundreds of small kingdoms throughout Westeros. -

El Ecosistema Narrativo Transmedia De Canción De Hielo Y Fuego”

UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA ESCOLA POLITE CNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “El ecosistema narrativo transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Jaume Mora Ribera Tutor/a: Nadia Alonso López Raúl Terol Bolinches GANDIA, 2019 1 Resumen Sagas como Star Wars o Pokémon son mundialmente conocidas. Esta popularidad no es solo cuestión de extensión sino también de edad. Niñas/os, jóvenes y adultas/os han podido conocer estos mundos gracias a la diversidad de medios que acaparan. Sin embargo, esta diversidad mediática no consiste en una adaptación. Cada una de estas obras amplia el universo que se dio a conocer en un primer momento con otra historia. Este conjunto de historias en diversos medios ofrece una narrativa fragmentada que ayuda a conocer y sumergirse de lleno en el universo narrativo. Pero a su vez cada una de las historias no precisa de las demás para llegar al usuario. El mundo narrativo resultante también es atractivo para otros usuarios que toman parte de mismo creando sus propias aportaciones. A esto se le conoce como narrativa transmedia y lleva siendo objeto de estudio desde principios de siglo. Este trabajo consiste en el estudio de caso transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego la saga de novelas que posteriormente se adaptó a la televisión como Juego de Tronos y que ha sido causa de un fenómeno fan durante la presente década. Palabras clave: Canción de Hielo y Fuego, Juego de Tronos, fenómeno fan, transmedia, narrativa Summary Star Wars or Pokémon are worldwide knowledge sagas. This popularity not just spreads all over the world but also over an age. -

Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones

Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gloria Makjanić Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Gloria Makjanić dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar, 2018. Makjanić 1 Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Gloria Makjanić, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Female Archetypes of Game of Thrones rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 13. rujna 2018. Makjanić 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Game of Thrones ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Archetypes ...................................................................................................................... -

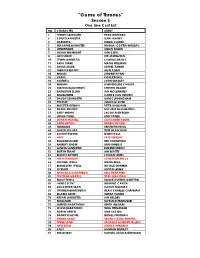

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nomination Press Release Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance F Is For Family • The Stinger • Netflix • Wild West Television in association with Gaumont Television Kevin Michael Richardson as Rosie Family Guy • Con Heiress • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Tom Tucker, Seamus Family Guy • Throw It Away • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Alex Borstein as Lois Griffin, Tricia Takanawa The Simpsons • From Russia Without Love • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe, Carl, Duffman, Kirk When You Wish Upon A Pickle: A Sesame Street Special • HBO • Sesame Street Workshop Eric Jacobson as Bert, Grover, Oscar Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The Planned Parenthood Show • Netflix • A Netflix Original Production Nick Kroll, Executive Producer Andrew Goldberg, Executive Producer Mark J. Levin, Executive Producer Jennifer Flackett, Executive Producer Joe Wengert, Supervising Producer Ben Kalina, Supervising Producer Chris Prynoski, Supervising Producer Shannon Prynoski, Supervising Producer Anthony Lioi, Supervising Producer Gil Ozeri, Producer Kelly Galuska, Producer Nate Funaro, Produced by Emily Altman, Written by Bryan Francis, Directed by Mike L. Mayfield, Co-Supervising Director Jerilyn Blair, Animation Timer Bill Buchanan, Animation Timer Sean Dempsey, Animation Timer Jamie Huang, Animation Timer Bob's Burgers • Just One Of The Boyz 4 Now For Now • FOXP •a g2e0 t1h Century -

As Tourism Ireland Adds Another New Section to Tapestry in Week Six of Its Global Game of Thrones® C…

18/09/2018 Flyer - Winter is ‘looming’ … as Tourism Ireland adds another new section to tapestry in week six of its global Game of Thrones® c… Winter is ‘looming’ … as Tourism Ireland adds another new section to tapestry in week six of its global Game of Thrones® campaign It’s week 6 of Tourism Ireland’s Game of Thrones® campaign, which is rolling out around the world to coincide with season 7, showcasing Northern Ireland to millions of fans. Tourism Ireland has released another time-lapse video of the weaving of the latest section of its Game of Thrones® tapestry, hanging in the Ulster Museum in Belfast. This week’s section includes a collection of scenes from “Eastwatch,” episode 5 of season 7: in Dragonstone, Daenerys once again convenes her war council. There, Jon receives a raven from Winterfell, warning that the Night King and his army of Wights are marching towards Eastwatch- by-the-Sea. After secretly meeting with Jaime, Tyrion rendezvouses with Davos and Gendry to escape Kings Landing and return to Dragonstone. Jon, Jorah, Davos and Gendry are joined by the Hound, Beric Dondarrion, Thoros of Myr Tormund Giantsbane, as they lead an expedition beyond the Wall to capture a Wight – alive. http://tourismirl.newsweaver.ie/Flyer/m0qde5q1ot2igo1g69mr6z?email=true&a=11&p=52227209 1/2 18/09/2018 Flyer - Winter is ‘looming’ … as Tourism Ireland adds another new section to tapestry in week six of its global Game of Thrones® c… As well as the time-lapse video, Tourism Ireland has also released another cinemagraph (or “living” photograph) this week as part of this campaign. -

Racialization, Femininity, Motherhood and the Iron Throne

THESIS RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES AS A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR Submitted by Aaunterria Treil Bollinger-Deters Department of Ethnic Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2018 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Ray Black Joon Kim Hye Seung Chung Copyright by Aaunterria Bollinger 2018 All Rights Reserved. ABSTRACT RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR This analysis dissects the historic preconceptions by which American television has erased and evaded race and racialized gender, sexuality and class distinctions within high fantasy fiction by dissociation, systemic neglect and negating artistic responsibility, much like American social reality. This investigation of high fantasy creative fiction alongside its historically inherited framework of hierarchal violent oppressions sets a tone through racialized caste, fetishized gender and sexuality. With the cult classic television series, Game of Thrones (2011-2019) as example, portrayals of white and nonwhite racial patterns as they define womanhood and motherhood are dichotomized through a new visual culture critical lens called the Colonizers Template. This methodological evaluation is addressed through a three-pronged specified study of influential areas: the creators of Game of Thrones as high fantasy creative contributors, the context of Game of Thrones -

Emotional Realism, Affective Labor, and Politics in the Arab Fandom of Game of Thrones Katty Alhayek University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Graduate Student Publication Communication Series 2017 Emotional Realism, Affective Labor, and Politics in the Arab Fandom of Game of Thrones Katty Alhayek University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs Alhayek, Katty, "Emotional Realism, Affective Labor, and Politics in the Arab Fandom of Game of Thrones" (2017). International Journal of Communication. 8. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_grads_pubs/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Graduate Student Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3740–3763 1932–8036/20170005 Emotional Realism, Affective Labor, and Politics in the Arab Fandom of Game of Thrones KATTY ALHAYEK1 University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA This article examines the Game of Thrones (GoT) fan phenomena in the Arab world. Although I contextualize GoT as a commodity within HBO’s global ambitions to attract a global audience, I study GoT Arab fans as an organized interpretive online community. I examine the Arabic fan Facebook page “Game of Thrones‒Official Arabic Page” (GoT- OAP), which has over 240,000 followers, as a case study of cultural -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. Emmy(s) to director(s). VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy Pilot February 22, 2014 Will Freeman is single, unemployed and loving it. But when Fiona, a needy, single mom and her oddly charming 11-year-old son, Marcus, move in next door, his perfect life is about to hit a major snag. Jon Favreau, Director 002 About A Boy About A Rib Chute May 20, 2014 Will is completely heartbroken when Sam receives a job opportunity she can’t refuse in New York, prompting Fiona and Marcus to try their best to comfort him. With her absence weighing on his mind, Will turns to Andy for his sage advice in figuring out how to best move forward. Lawrence Trilling, Directed by 003 About A Boy About A Slopmaster April 15, 2014 Will throws an afternoon margarita party; Fiona runs a school project for Marcus' class; Marcus learns a hard lesson about the value of money. Jeffrey L. Melman, Directed by 004 Alpha House In The Saddle January 10, 2014 When another senator dies unexpectedly, Gil John is asked to organize the funeral arrangements. Louis wins the Nevada primary but Robert has to face off in a Pennsylvania debate to cool the competition. Clark Johnson, Directed by 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series.