1 a Book and Its Critics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“These Stones Shall Be for a Memorial”: a Discussion of the Abolition of Circumcision in the Kitāb Al‐Mağdal

Nikolai N. Seleznyov Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies Russian State University for the Humanities [email protected] “THESE STONES SHALL BE FOR A MEMORIAL”: A DISCUSSION OF THE ABOLITION OF CIRCUMCISION IN THE KITĀB AL‐MAĞDAL The question of Christian freedom from Old Testament law became especially controversial since it concerned the practice of circumcis‐ ion. The obvious practical considerations for excusing Christianized Gentiles from the demands of the Jewish tradition were not the only reason to discuss the custom. When Paul told the church in Rome that circumcision was rather a matter of the heart (Rom 2:29), he un‐ doubtedly referred to the words of the prophets who preached cir‐ cumcision of “the foreskin of the hearts” (Deut 10:16–17; Jer 4:3–4). Bodily circumcision, including that of Christ Himself, remained a subject of debate during subsequent Christian history, though the problem of fulfilling the stipulations of Old Testament law was gen‐ erally no longer actually present in historical reality.1 The present study will provide an interesting example of how a similar discussion of the same subject regained and retained its actuality in the context of Christian‐Muslim relations in the medieval Middle East. The ex‐ ample in question is a chapter on the abolition of circumcision in the comprehensive ‘Nestorian’ encyclopedic work of the mid‐10th–early 11th century entitled Kitāb al‐Mağdal.2 ———————— (1) A. S. JACOBS, Christ Circumcised: A Study in Early Christian History and Difference (Divinations: Rereading Late Ancient Religion), Philadelphia, 2012. (2) M. STEINSCHNEIDER, Polemische und apologetische Literatur in arabischer Sprache, zwischen Muslimen, Christen und Juden: nebst Anhängen verwandten In‐ halts, mit Benutzung handschriftlicher Quellen (Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 6.3), Leipzig, 1877, pp. -

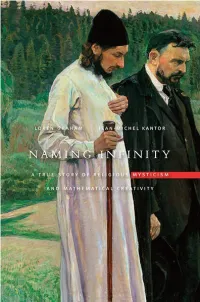

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Orthodox Political Theologies: Clergy, Intelligentsia and Social Christianity in Revolutionary Russia

DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2020.08 ORTHODOX POLITICAL THEOLOGIES: CLERGY, INTELLIGENTSIA AND SOCIAL CHRISTIANITY IN REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA Alexandra Medzibrodszky A DISSERTATION in History Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2020 Dissertation Supervisor: Matthias Riedl DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2020.08 Copyright Notice and Statement of Responsibility Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions and no materials previously written and/or published by another person unless otherwise noted. CEU eTD Collection ii DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2020.08 Technical Notes Transliteration of Russian Cyrillic in the dissertation is according to the simplified Library of Congress transliteration system. Well-known names, however, are transliterated in their more familiar form, for instance, ‘Tolstoy’ instead of ‘Tolstoii’. All translations are mine unless otherwise indicated. Dates before February 1918 are according to the Julian style calendar which is twelve days behind the Gregorian calendar in the nineteenth century and thirteen days behind in the twentieth century. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The Historical Setting On July 3, 1913 some four hundred monks of the Athonite monastery of St. Panteleimon fled to one of their dormitory buildings and set to work barricading the entrances with bed boards. Bayoneted rifles in hand, sailors of the Russian Imperial Navy surrounded the building while their officers exhorted the unarmed monks to give up peacefully. To no avail. Prepared for martyrdom but hoping in God's help, the monks sang, prayed, did prostrations, and took up icons and crosses to defend themselves. Finally the trumpet rang out with the command to "shoot," and the calm of the Holy Mountain was rent by the roar ... not of firearms, but of fire hoses. After an hour-long "cold shower" dampened the monks' spirits, the sailors rushed the building and began to drag recalcitrant devotees of the contemplative life out of the corridors. These events took place on a narrow peninsula in northern Greece some forty miles long by five miles wide, named "Mt. Athos" after the 6,000 foot mountain towering over the end of it. Since the tenth century this stretch of land has been set aside for the exclusive use of Eastern Orthodox monks, a status instituted by the Byzantine Empire and maintained by the Turks after they conquered it in 1453. Though located in Greece it eventually became an international center for Orthodox monasticism, and the nineteenth century saw such a mass immigration of Russians that by the beginning of the twentieth the mountain was really more Russian than Greek. That situation was not to last long, and the events narrated above marked the beginning of the end. -

Imiaslavie As an Ancient Trajectory of Eastern Orthodox Monastic Theology

Vasilije Vranić Imiaslavie as an Ancient Trajectory of Eastern Orthodox Monastic Theology Imiaslavie is a theological phenomenon that emerged among Russian monks at the beginning of the 20th century. It rapidly spread and became popular among the Slavic monks on Mount Athos. Imiaslavie taught that the essence of God is contained in His name. A connection is evident between Imiaslavie and the ancient mystical theology of Second Temple Judaism, which was forged by the transmission of the ideas through the centuries within the ascetic milieu. It is interesting to note that the underlying concept of Imiaslavie continuously exists in the mystical theologies across religions (Judaism and Christianity) and periodically surfaces in the theological discourse. In ancient Jewish theology, it is evident in the mystical teachings regarding the sacred tetragrammaton – YHWH, which was accorded divine attributes. Another trajectory of the same religious tradition is the Shem Theology, which contemplates the divine name. In early Christianity the teachings on the divine name are transmitted through the works of the monastic mysticism, namely the writings associated with the invocation of the name of God in the “Jesus Prayer.” This prayer exists from at least the sixth century as a distinct teaching, and flourishes in the 14th century when it receives its theological expression. It continues to exist in a dominant manner in the Eastern Christian Spirituality to this day. In my paper, I will seek to explore the theological foundation of Imiaslavie as a teaching to which Slavic monasticism gave expression, although its tenets were present in the Eastern monastic spirituality for many centuries. -

Anthony) Bulatovich (1870–1919) and the Imiaslavie (Onomatodoxy, Name‐Glorifying

510 Scrinium X (2014). Syrians and the Others scribed in Byzantine texts; C) the vesting prayers according to the Textus Receptus of the Greek rite. The edition is provided with 79 black‐and‐white illustrations, 22 colour plates, a bibliography, and an index. T. Sénina (mon. Kassia) Saint Petersburg State University of Aerospace Instrumentation TWO BOOKS ON FR ANTONII (ANTHONY) BULATOVICH (1870–1919) AND THE IMIASLAVIE (ONOMATODOXY, NAME‐GLORIFYING) Tom DYKSTRA, Hallowed Be Thy Name: The Name‐ Glorifying Dispute in the Russian Orthodox Church and on Mt. Athos, 1912–1914, St Paul, MN: OCABS Press, 2013, p. 244. ISBN 1‐60191‐030‐4 This book, which uses an icon of Fr Antonii (Bulatovich) on the front cover, is a reworking of the author’s 1988 PhD thesis defended at the St. Vladimir Theological Seminary under the supervision of the late Fr John Meyendorff (1926–1992). At the time, it was certainly a pio‐ neering work, especially for its English‐speaking audience. The abun‐ dant flow of publications in Russian would start only ca 1994. A most systematic but biased account of the struggle on Mt. Athos was then available through a small monograph by Constantine Papoulidis in Greek (1977). There was, moreover, a largely historical article by a famous Jesuit specialist in Russian theology Bernhard Schultze (1902– 1990) (published in 1951 in German). And, finally, Antoine Nivière, a French specialist in the topic, had started to work simultaneously with Tom Dykstra and, at first, without them knowing each other. However, unlike Antoine Nivière, Tom Dykstra was not especially interested in the impact of the Imiaslavie on the so‐called “Russian religious philosophy” (Florensky, S. -

1 Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor a Comparison of Two Cultural Approaches to Mathematics: France and Russia, 1890-19301 “

1 Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor A Comparison of Two Cultural Approaches to Mathematics: France and Russia, 1890-19301 “. das Wesen der Mathematik liegt gerade in ihrer Freiheit” Georg Cantor, 18832 Many people would like to know where new scientific ideas come from, and how they arise. This subject is of interest to scientists of course, historians and philosophers of science, psychologists, and many others. In the case of mathematics, new ideas often come in the form of new “mathematical objects:” groups, vector spaces, sets, etc. Some people think these new objects are invented in the brains of mathematicians; others believe they are in some sense discovered, perhaps in a platonistic world. We think it would be interesting to study how these questions have been confronted by two different groups of mathematicians working on the same problems at the same time, but in two contrasting cultural environments. Will the particular environment influence the way mathematicians in each of the two groups see their work, and perhaps even help them reach conclusions different from those of the other group? We are exploring this issue 2 in the period 1890-1930 in France and Russia on the subject of the birth of the descriptive theory of sets. In the Russian case we have found that a particular theological view – that of the “Name Worshippers” – played a role in the discussions of the nature of mathematics. The Russian mathematicians influenced by this theological viewpoint believed that they had greater freedom to create mathematical objects than did their French colleagues subscribing to rationalistic and secular principles. -

Introduction

Introduction The Russian Idea: In Search of a New Identity Wendy Helleman “The morning that will break over Russia after the nightmarish revolutionary night will be rather the foggy ‘gray morning’ that the dying Blok prophe- sied.… After the dream of world hegemony, of conquering planetary worlds, of physiological im- mortality, of earthly paradise, – back where we started, with poverty, backwardness, and slavery – and perhaps national humiliation as well. A gray morning.”1 This was the prediction of Fedotov, as early as the 1940s, and it has proven to be remarkably accurate. The transition has been slow, laborious, and painful. Turning the Communist USSR into a modern Russian state was far more diffi- cult than most could have imagined. As numerous former satellite states declared independence, Russia was reduced to a pale shadow of the imperial USSR, and its role on the world stage diminished accordingly. Communists, though they will not easily return to power, continue to cast a strong shadow over every at- tempt at revising collectivist structures; nor is it easy to change attitudes deeply embedded in the 20th-century Russian mind. In a context of continuing eco- nomic and political instability it is not surprising that issues of Russian identity and the “Russian Idea” occupy a central place in public discussion.2 1 F. P. Fedotov, Sud′ba i grekhi Rossii: Izbrannye stat′i po filosofii russkoi istorii i kul′tury [The fate and sins of Russia: Selected articles on the philosophy of Russian history and culture] (St. Peters- burg: Izdatel′stvo “Sofiia,” 1991–92), 2: 198; cf. -

Myth, Religion, and Magic Versus Literature, Sign and Narrative

religions Editorial East-European Critical Thought: Myth, Religion, and Magic versus Literature, Sign and Narrative Dennis Ioffe Département D’enseignement de Langues et Lettres, Faculté de Lettres, Traduction et Communication, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Campus du Solbosch, CP 175, Avenue F.D. Roosevelt, 50, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium; [email protected] Abstract: The Introductory article offers a general overview of the highly complicated topic of religious and mythological consciousness discussed in sub-species narrative critique and literary theory. It also provides a detailed context for the wide array of religious matters discussed in this special volume of Religions. Each of the nineteen papers is positioned within its own particular thematic discourse. Keywords: Russian Paganism; mythology; theory; narrative; semiotics & semiosis Our special edition concentrates on Slavic religions and mythology as evidenced in theory, literature and folklore. The nineteen articles deal with various forms of pre- Christian religious beliefs, myths and ritual practices of the Slavs, which infiltrate into ‘dual beliefs’ (such as remnants of ‘dvoeverie’). Also addressed are the uneasy ways in which Christian Orthodoxy has handled the various challenges posed by popular belief and mythology. Most existing studies are somewhat dated, prompting a growing need for fresh scholarly approaches and reassessments concerning both officially sanctioned and Citation: Ioffe, Dennis. 2021. heterodox religious practices. A basic aim, therefore, is to bring together archaic forms East-European Critical Thought: of religious spirituality, creative literature, folklore, philosophy and theology, a synthesis Myth, Religion, and Magic versus which, we hope, will illumine the ways in which mythologies and religious traditions Literature, Sign and Narrative. -

Thomas Cattoi, Curriculum Vitae

Thomas Cattoi, Curriculum Vitae Thomas Cattoi Curriculum Vitae _______________________________________________________________________________ • Associate Professor in Christology and Cultures and Dwan Family Chair of Inter-religious Dialogue, Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University (formerly Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley)/Graduate Theological Union Education • STL, Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University, 2011 • PhD in Systematic and Comparative Theology, Boston College, 2006 • MPhil in Social Studies, School of Slavonic and European Studies, London, 2002 • MSc in Economics and Philosophy, London School of Economics (LSE), 1996 • BA (Hons.) in Economics and Philosophy (PPE), Oxford University, 1995 Additional qualifications • Licensed Psychotherapist in the State of California (LMFT 106457) • Holder of nihil obstat from Congregation for Catholic Education (April 10th, 2018) Books • Theologies of the Sacred Image in Theodore the Studite and Bokar Rinpoche (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press), forthcoming • Seeking wisdom, embracing compassion: a Philokalic commentary to Tsong kha pa’s ‘Great Treatise’, in “Christian Commentaries on non-Christian texts” Series (ed. Catherine Cornille, Peeters/Brill), forthcoming • With Carol Anderson (ed.), Handbook on Buddhist-Christian Studies (Routledge, 2021) • With Brandon Gallaher and Paul Ladouceur (eds.), Eastern Orthodoxy and World Religions: The Theology and Practice of Interreligious Encounter in the Contemporary Christian East (Brill, 2021) • With David Odorisio -

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

The Laments of the Philosophers Over Alexander the Great According to the Blessed Compendium of Al‐Makīn Ibn Al‐ʿamīd

Nikolai N. Seleznyov Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies Russian State University for the Humanities [email protected] THE LAMENTS OF THE PHILOSOPHERS OVER ALEXANDER THE GREAT ACCORDING TO THE BLESSED COMPENDIUM OF AL‐MAKĪN IBN AL‐ʿAMĪD The thirteenth‐century Christian Arabic historian Ğirğis al‐Makīn ibn al‐ʿAmīd — the author of the two‐volume universal history entitled The Blessed Compendium (al‐Mağmūʿ al‐mubārak) — was a rather para‐ doxical figure. Frequently defined as “a Coptic historian,”1 he was not a Copt, and even though his Blessed Compendium is well known not only in Eastern Christian and Muslim historiography, but also in Western scholarship since its inception, the first part of this historical work still remains unpublished. This first part, however, contains vast material that would undoubtedly interest scholars studying the intellectual heritage of the medieval Middle East. The following arti‐ cle deals with one section of al‐Makīn’s famous work. THE AUTHOR: HIS ORIGINS AND LIFE TRAJECTORY Al‐Makīn’s autobiographical note on his origins was initially ap‐ pended to his history and was then published as part of the Historia ———————— (1) See, for instance: Cl. CAHEN, R. G. COQUIN, “al‐Makīn b. al‐ʿAmīd,” in: The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New edition, 11 vols. & Suppl., Leiden, 1986– 2004, vol. 6, p. 143:2; S. Kh. SAMIR, “al‐Makīn, Ibn al‐ʿAmīd,” in: The Coptic Encyclopedia, ed. by A. S. ATIYA, 8 vols., New York, Toronto, Oxford [etc.], 1991, vol. 5, p. 1513; F.‐Ch. MUTH, “Fāṭimids,” in: Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, 4 vols., Wiesbaden, 2004–2010, vol. 2, p.