Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Russia: National Interests and Emerging Foreign Policy Perceptions Kortunov, Andrei; Volodin, Andrei

www.ssoar.info Contemporary Russia: national interests and emerging foreign policy perceptions Kortunov, Andrei; Volodin, Andrei Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Forschungsbericht / research report Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kortunov, A., & Volodin, A. (1996). Contemporary Russia: national interests and emerging foreign policy perceptions. (Berichte / BIOst, 33-1996). Köln: Bundesinstitut für ostwissenschaftliche und internationale Studien. https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-42550 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

"Russian Idea" of F.M. Dostoevsky: from Soilness to Universality

RUDN Journal of Philosophy 2021 Vol. 25 No. 1 15—24 Âåñòíèê ÐÓÄÍ. Ñåðèÿ: ÔÈËÎÑÎÔÈß http://journals.rudn.ru/philosophy DOI: 10.22363/2313-2302-2021-25-1-15-24 Research Article / Научная статья "Russian Idea" of F.M. Dostoevsky: from Soilness to Universality Sergei A. Nizhnikov Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 6, Miklukho-Maklaya St., Moscow, 117198, Russian Federation, [email protected] Abstract. The author reveals Fyodor Dostoevsky's works main features, his importance for Russian and world philosophy. The researcher analyzes the concept of "Russian Idea" introduced by Dostoyevsky, which became a study subject in Russian philosophy's subsequent history. The polemics that arose regarding the characteristics of Dostoevsky's soilness (Pochvennichestvo) ideology and his interpretation of the Russian Idea in his Pushkin Speech and subsequent comments in A Writer's Diary are unveiled. The author concludes that Dostoevsky overcomes the limitations of soilness and comes to universalism. The universal for him does not have a rootless cosmopolitan character but is born from the national's heyday. Diversity adorns the truth, and national diversity enamels humankind. People's real unity is in that all-human value that is found in the highest examples of each national culture. The truth is not in rootless cosmopolitanism or nationalism — it is in the "golden mean," which, in our opinion, the writer-philosopher sought to express. Dostoevsky wanted to rise above the dispute, to recognize the points of view of the Slavophiles and Westernizers as one-sided, to get out of any particularity to universality. Keywords: Dostoevsky, Russian idea, soilness, universality, anthropology of hesychasm, all-human, nationality Funding and Acknowledgement of Sources. -

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Thomas De Simone, B.A., M.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Nicholas Breyfogle, Advisor David Hoffmann Robin Judd Predrag Matejic Copyright by Peter T. De Simone 2012 Abstract In the mid-seventeenth century Nikon, Patriarch of Moscow, introduced a number of reforms to bring the Russian Orthodox Church into ritualistic and liturgical conformity with the Greek Orthodox Church. However, Nikon‘s reforms met staunch resistance from a number of clergy, led by figures such as the archpriest Avvakum and Bishop Pavel of Kolomna, as well as large portions of the general Russian population. Nikon‘s critics rejected the reforms on two key principles: that conformity with the Greek Church corrupted Russian Orthodoxy‘s spiritual purity and negated Russia‘s historical and Christian destiny as the Third Rome – the final capital of all Christendom before the End Times. Developed in the early sixteenth century, what became the Third Rome Doctrine proclaimed that Muscovite Russia inherited the political and spiritual legacy of the Roman Empire as passed from Constantinople. In the mind of Nikon‘s critics, the Doctrine proclaimed that Constantinople fell in 1453 due to God‘s displeasure with the Greeks. Therefore, to Nikon‘s critics introducing Greek rituals and liturgical reform was to invite the same heresies that led to the Greeks‘ downfall. -

“These Stones Shall Be for a Memorial”: a Discussion of the Abolition of Circumcision in the Kitāb Al‐Mağdal

Nikolai N. Seleznyov Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies Russian State University for the Humanities [email protected] “THESE STONES SHALL BE FOR A MEMORIAL”: A DISCUSSION OF THE ABOLITION OF CIRCUMCISION IN THE KITĀB AL‐MAĞDAL The question of Christian freedom from Old Testament law became especially controversial since it concerned the practice of circumcis‐ ion. The obvious practical considerations for excusing Christianized Gentiles from the demands of the Jewish tradition were not the only reason to discuss the custom. When Paul told the church in Rome that circumcision was rather a matter of the heart (Rom 2:29), he un‐ doubtedly referred to the words of the prophets who preached cir‐ cumcision of “the foreskin of the hearts” (Deut 10:16–17; Jer 4:3–4). Bodily circumcision, including that of Christ Himself, remained a subject of debate during subsequent Christian history, though the problem of fulfilling the stipulations of Old Testament law was gen‐ erally no longer actually present in historical reality.1 The present study will provide an interesting example of how a similar discussion of the same subject regained and retained its actuality in the context of Christian‐Muslim relations in the medieval Middle East. The ex‐ ample in question is a chapter on the abolition of circumcision in the comprehensive ‘Nestorian’ encyclopedic work of the mid‐10th–early 11th century entitled Kitāb al‐Mağdal.2 ———————— (1) A. S. JACOBS, Christ Circumcised: A Study in Early Christian History and Difference (Divinations: Rereading Late Ancient Religion), Philadelphia, 2012. (2) M. STEINSCHNEIDER, Polemische und apologetische Literatur in arabischer Sprache, zwischen Muslimen, Christen und Juden: nebst Anhängen verwandten In‐ halts, mit Benutzung handschriftlicher Quellen (Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 6.3), Leipzig, 1877, pp. -

February, 2010 Kevin J. Mckenna EDUCATION

February, 2010 Kevin J. McKenna EDUCATION: Ph.D. Degree 1977, University of Colorado: Slavic Languages and Literatures M.A. Degree 1971, University of Colorado: Russian Literature B.A. Degree 1970, Oklahoma State University (OSU): Humanities NDEA Intensive Slavic Language Institutes at the University of Kansas and Leningrad State University, 1968, 1969, 1970 Dissertation Title: Catherine the Great's ‘Vsiakaia Vsiachina’ and The ‘Spectator’ Tradition of the Satirical Journal of Morals and Manners RESEARCH GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS: Consultant and collaborator to U.S. Department of Education/Department of State grant to develop a nationwide portfolio project for High School through College Critical Foreign Language Programs in Arabic, Chinese and Russian (2009-2013) Consultant and collaborator to U.S. Department of Education Title VI National Resource Center grant proposal to promote and strengthen international studies-based curricula in higher education (PI Professor Ned McMahon) Recipient of the Robert V. Daniels Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Field of International Studies, May 7, 2009 Nominee for Kroepsch-Maurice Outstanding Teacher Award, 2009/2010 U.S. State Department grant ($350,000.00) “Karelia/Vermont Sustainable Development Partnership, 2007-2010.” Co-Principal Investigator with Prof. Pat Stokowski. Named as UVM Woodrow Wilson Fellow for "Scholars as Teachers," 2000-2001 Named as UVM Service-Learning Faculty Fellow, 2000-2001 2 RESEARCH GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS: (continued) Principal Investigator for Department -

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia © 2014 Brad Alexander Gordon A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi April, 2014 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Joshua First Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Dr. Valentina Iepuri 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………p. 3 Part I: Interwar Émigrés and Their Literary Contributions Introduction: The Russian Intelligentsia and the National Question………………….............................................................................................p. 4 Chapter 1: Russia’s Eschatological Quest: Longing for the Divine…………………………………………………………………………………p. 14 Chapter 2: Nature, Death, and the Peasant in Russian Literature and Art……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 26 Chapter 3: Tsvetaeva’s Tragedy and Tolstoi’s Triumph……………………………….........................................................................p. 36 Part II: The Émigrés Return Introduction: Nostalgia’s Role in Contemporary Literature and Film……………………………………………………………………………………p. 48 Chapter 4: “Old Russia” in Contemporary Literature: The Moral Dilemma and the Reemergence of the East-West Debate…………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Chapter 5: Restoring Traditional Russia through Post-Soviet Film: Nostalgia, Reconciliation, and the Quest -

The Fate of Russia: Several Observations on "New" Russian Identity

THE FATE OF RUSSIA: SEVERAL OBSERVATIONS ON "NEW" RUSSIAN IDENTITY S. V. Kortunov Introduction Russia is going through a complicated historical period. A search is taking place for the optimal path of development and the best form of state structure. Social-economic ties are changing in a fundamental manner. Along with the not insignificant positive results of the political and economic reforms that are being carried out, negative processes in the economy, in the social sphere and in the relations between the center and the regions are becoming clearly evident. On the international arena, Russia is confronting the desire of a number of countries to use the transitional period to promote their economic and political interests, often to the detriment of Russians' national aspirations. Three overarching factors characterize the Russian domestic situation: the continuing systematic crisis in society, which began in the Soviet period; the country's development crisis, which appeared during the transitional period; and the difficulties of overcoming the residues of the former totalitarian regime. (These problems are in turn linked to the global crisis that has resulted from the collapse of the Cold War order.) It is obvious that the contemporary crisis is on a larger scale than the problems associated with the February and October 1917 Revolutions, the abolition of serfdom, and even the Time of Troubles. We are discussing a crisis that is comparable only to the epic transformation of the 13th century, when the collapse of one superethnos (Kievian Russ) occurred and a new nation, country, and civilization (the Russian superethnos) began to be born. -

The Evaluation of Ideological Trends in Recent Soviet Literary Scholarship

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 255 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Henrietta Mondry The Evaluation of Ideological Trends in Recent Soviet Literary Scholarship Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Henrietta Mondry - 9783954791873 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:43:19AM via free access S lavistische B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER• JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 255 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER Henrietta Mondry - 9783954791873 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:43:19AM MÜNCHEN via free access 00050424 HENRIETTA MONDRY THE EVALUATION OF IDEOLOGICAL TRENDS IN RECENT SOVIET LITERARY SCHOLARSHIP VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHENHenrietta Mondry - 9783954791873 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:43:19AM 1990 via free access ISBN 3-87690-456-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1990Henrietta Mondry - 9783954791873 Abteilung der Firma KubonDownloaded & Sagner, from PubFactory München at 01/10/2019 03:43:19AM via free access 00050424 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. METHODOLOGICAL BASIS. THE LENIN-PLEKHANOV -

Download Fulltext

Convention-2019 Convention 2019 “Modernization and Multiple Modernities” Volume 2020 Conference Paper Retro-Utopia Temptation of Archangel Mikhail Groys By Vadim Mesyats N.V.Barkovskaya Ural State Pedagogical University, Ekaterinburg, Russia Abstract This article discusses the retro-utopian novel Temptation of Archangel Mikhail Groys by Vadim Mesyats. The novel explores an alternative scenario of overcoming the bleak present and entering the future by going back to a past represented by the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The novel is set in Belarus in 2013. Belarus is shown as the last stronghold of socialism, as the country that has managed to preserve both its recent and more distant past, as the ’paradise regained’, whose boundaries remain transparent for Russia and for the European Union. Belarus is a multi-confessional and (historically) multi-ethnic country, allowing it to uphold the ‘common cause’ of uniting brother nations and initiating their spiritual transformation. Apart from the obvious allusion to N. Fyodorov’s philosophy, the novel also contains multiple reminiscences Corresponding Author: to the works of V. Soloviev, Gorky’s The Confession, contemporary neo-paganism and N.V.Barkovskaya [email protected] discussions of contemporary historians about the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as the second centre for consolidating Russian lands. Received: Month 2020 Accepted: Month 2020 Keywords: neo-mythologism, neo-paganism, modern Russian prose, alternative Published: 28 September 2020 history, Soviet nostalgia Publishing services provided by Knowledge E N.V.Barkovskaya. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons 1. Introduction Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and The novel of Vadim Mesyats was published in Issues 2 and 3 of the journal Ural in 2015 redistribution provided that the under the title The Legion of Archangel Mikhail Groys. -

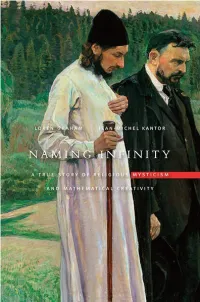

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Why Gennady Zyuganov's Communist Party Finished First 187

Why Gennady Zyuganov 's Communist Party Finished First ALEXANDER S. TSIPKO t must be said that the recent Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) victory in the Duma elections was not a surprise. All Russian Isociologists predicted Gennady Zyuganov's victory four months before the elections on 17 December 1995. The KPRF, competing against forty-two other parties and movements, was expected to receive slightly more than 20 percent of the votes (it received 21.7 percent) and more than fifty deputy seats according to single-mandate districts (it received fifty-eight). Before the elections, there were obvious signals that the vote would go to the KPRF. It was expected that the older generation would vote for the KPRF. The pensioners, who suffered the most damage from shock therapy, would most certainly vote for members representing the ancién regime (for social guarantees, work, and security; things the former social system gave them). Even before the elections, the image of the KPRF as a real party had been formed. In my opinion, the victory of the KPRF in the elections is a critical event in Russia's post-Soviet history, which demands both more attention and clearer comprehension. The simplistic reason often given for the KPRF victory was the sudden introduction of the monetarist method of reform, which resulted in an inevitable leftward shift in the mood of society and a restoration of neo-communism. The heart of the problem is not so simple and orderly-it is found in Russian affairs and in Russian nature. First of all, it is evident that the Duma election victory of KPRF leader Gennady Zyuganov has a completely different moral and political meaning than the victory of the neo-communist party of Aleksander Kwasniewski in the November 1995 Polish presidential elections. -

The Struggle for Spiritual Supremacy: Dostoevsky's Philosophy Or History and Eschatology

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1994 The Struggle for Spiritual Supremacy: Dostoevsky's Philosophy or History and Eschatology Andrew Wender Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the History Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Wender, Andrew, "The Struggle for Spiritual Supremacy: Dostoevsky's Philosophy or History and Eschatology" (1994). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 339. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/339 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Struggle for Spiritual Supremacy: Dostoevsky's Philosophy or History and Eschatology Andrew Wender Presented to Prof. George Mariz and Prof. Susan Costanzo Project Advisers Honors 490 - Senior Project June 6, 1994 • ............._ Honors Program HONORS fflESIS In presenting this Honors Paper in partial requirements for a bachelor's degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood that any publication of this thesis for commercial pur:uoses or for financial eain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Bellingham, Washington 98225-9089 □ f2061 676-3034 An Equal Oppartunit_v University Table of Contents Page I. Introduction . 2 II. Historical Context And Intellectual Development or Dostoevsky's Philosophy or History ..............................