An Investigation Into the Contribution Made by Primary Art Coordinators to the Development of the Teaching of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Art Magazine Issue # Sixteen December | January Twothousandnine Spedizione in A.P

contemporary art magazine issue # sixteen december | january twothousandnine Spedizione in a.p. -70% _ DCB Milano NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 KAREN KILIMNIK NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 WadeGUYTON BLURRY CatherineSULLIVAN in collaboration with Sean Griffin, Dylan Skybrook and Kunle Afolayan Triangle of Need VibekeTANDBERG The hamburger turns in my stomach and I throw up on you. RENOIR Liquid hamburger. Then I hit you. After that we are both out of words. January - February 2009 DEBUSSY URS FISCHER GALERIE EVA PRESENHUBER WWW.PRESENHUBER.COM TEL: +41 (0) 43 444 70 50 / FAX: +41 (0) 43 444 70 60 LIMMATSTRASSE 270, P.O.BOX 1517, CH–8031 ZURICH GALLERY HOURS: TUE-FR 12-6, SA 11-5 DOUG AITKEN, EMMANUELLE ANTILLE, MONIKA BAER, MARTIN BOYCE, ANGELA BULLOCH, VALENTIN CARRON, VERNE DAWSON, TRISHA DONNELLY, MARIA EICHHORN, URS FISCHER, PETER FISCHLI/DAVID WEISS, SYLVIE FLEURY, LIAM GILLICK, DOUGLAS GORDON, MARK HANDFORTH, CANDIDA HÖFER, KAREN KILIMNIK, ANDREW LORD, HUGO MARKL, RICHARD PRINCE, GERWALD ROCKENSCHAUB, TIM ROLLINS AND K.O.S., UGO RONDINONE, DIETER ROTH, EVA ROTHSCHILD, JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC SCHNYDER, STEVEN SHEARER, JOSH SMITH, BEAT STREULI, FRANZ WEST, SUE WILLIAMS DOUBLESTANDARDS.NET 1012_MOUSSE_AD_Dec2008.indd 1 28.11.2008 16:55:12 Uhr Galleria Emi Fontana MICHAEL SMITH Viale Bligny 42 20136 Milano Opening 17 January 2009 T. +39 0258322237 18 January - 28 February F. +39 0258306855 [email protected] www.galleriaemifontana.com Photo General Idea, 1981 David Lamelas, The Violent Tapes of 1975, 1975 - courtesy: Galerie Kienzie & GmpH, Berlin L’allarme è generale. Iper e sovraproduzione, scialo e vacche grasse si sono tra- sformati di colpo in inflazione, deflazione e stagflazione. -

Dissertação Final Corrigida

Universidade Estadual Paulista “Julio de Mesquita Filho” Instituto de Artes ALINE PIRES LUZ A ARTE PSICODÉLICA E SUA RELAÇÃO COM A ARTE CONTEMPORÂNEA NORTE-AMERICANA E INGLESA DOS ANOS 1960: uma dissolução de fronteiras São Paulo 2014 ALINE PIRES LUZ A ARTE PSICODÉLICA E SUA RELAÇÃO COM A ARTE CONTEMPORÂNEA NORTE-AMERICANA E INGLESA DOS ANOS 1960: uma dissolução de fronteiras Dissertação apresentada ao curso de Pós- Graduação em Artes, do Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Artes Visuais, Área de concentração: História da Arte. Linha de Pesquisa: Abordagens Teóricas, Históricas e Culturais da Arte. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Omar Khouri. São Paulo 2014 ALINE PIRES LUZ A ARTE PSICODÉLICA E SUA RELAÇÃO COM A ARTE CONTEMPORÂNEA NORTE-AMERICANA E INGLESA DOS ANOS 1960: uma dissolução de fronteiras Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Artes Visuais no curso de Pós-Graduação em Artes, do Instituto de Artes da Universidades Estadual Paulista – UNESP, com área de concentração em História da Arte, pela seguinte banca examinadora: __________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Omar Khouri Instituto de Artes (UNESP) – Orientador. __________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Sérgio Mauro Romagnolo Instituto de Artes (UNESP) __________________________________________ Dr. Júlio César Mendonça Pontifícia Universidade Católica – PUC/SP São Paulo, 10 de Junho de 2014 RESUMO Tem-se por objetivo situar a produção de arte psicodélica vinculada ao movimento de contracultura da década de 1960, em relação à chamada arte contemporânea, que se iniciava no mesmo período e que pode ser tomada como uma arte que se deu no âmbito mainstream , por circular nas principais galerias, museus e fazer parte da História da Arte. -

ARQUITECTURA E AUTONOMIA EXPERIMENTAÇÃO NA PERIURBANIDADE António Coxito

ARQUITECTURA E AUTONOMIA EXPERIMENTAÇÃO NA PERIURBANIDADE António Coxito Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Arquitectura ORIENTADORES: Professor Doutor João Soares Professor Doutor Joaquim Moreno Professor Doutor João Mendes Ribeiro ÉVORA, JANEIRO 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ARQUITECTURA E AUTONOMIA EXPERIMENTAÇÃO NA PERIURBANIDADE António Coxito Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Arquitectura ORIENTADORES: Professor Doutor João Soares Professor Doutor Joaquim Moreno Professor Doutor João Mendes Ribeiro ÉVORA, JANEIRO 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA DEDICATÓRIA Para a Luísa, o plano onde me desloco, suficientemente inclinado para cultivar a imponderabilidade. AGRADECIMENTOS Ao arquitecto João Soares, pela confiança depositada na razão de ser da minha dúvida. Pelas incansáveis sessões de acompanhamento onde foi feita a sugestão subliminar de referências pecaminosas que se revelariam radicais. Mas também pela definição de limites. Ao arquitecto Joaquim Moreno, consciência sempre presente do fascínio e responsabilidade de um trabalho de investigação. Particularmente, pela informação disponibilizada para o enquadramento das utopias americanas e da sua counter[european]culture. Ao doutor Jorge Rivera, pelas expressões de apreensão sobre as questões epistemológicas, que levaram ao seu acerto e rigor. Ao arquitecto João Mendes Ribeiro, pelas chamadas de atenção à forma do documento como meio de comunicação inteligível do conhecimento. Ao Luís Coutinho e à Graça Passos, que me receberam na Herdade da Tojeira e me proporcionaram as condições logísticas necessárias para desenvolver a minha investigação através da acção. Ao Domingos, ao Zé Gato, ao Lopes e ao Miguel Gomes, pelo apoio muscular e anímico durante a experimentação. -

La Mamelle and the Pic

1 Give Them the Picture: An Anthology 2 Give Them The PicTure An Anthology of La Mamelle and ART COM, 1975–1984 Liz Glass, Susannah Magers & Julian Myers, eds. Dedicated to Steven Leiber for instilling in us a passion for the archive. Contents 8 Give Them the Picture: 78 The Avant-Garde and the Open Work Images An Introduction of Art: Traditionalism and Performance Mark Levy 139 From the Pages of 11 The Mediated Performance La Mamelle and ART COM Susannah Magers 82 IMPROVIDEO: Interactive Broadcast Conceived as the New Direction of Subscription Television Interviews Anthology: 1975–1984 Gregory McKenna 188 From the White Space to the Airwaves: 17 La Mamelle: From the Pages: 87 Performing Post-Performancist An Interview with Nancy Frank Lifting Some Words: Some History Performance Part I Michele Fiedler David Highsmith Carl Loeffler 192 Organizational Memory: An Interview 19 Video Art and the Ultimate Cliché 92 Performing Post-Performancist with Darlene Tong Darryl Sapien Performance Part II The Curatorial Practice Class Carl Loeffler 21 Eleanor Antin: An interview by mail Mary Stofflet 96 Performing Post-Performancist 196 Contributor Biographies Performance Part III 25 Tom Marioni, Director of the Carl Loeffler 199 Index of Images Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), San Francisco, in Conversation 100 Performing Post-Performancist Carl Loeffler Performance or The Televisionist Performing Televisionism 33 Chronology Carl Loeffler Linda Montano 104 Talking Back to Television 35 An Identity Transfer with Joseph Beuys Anne Milne Clive Robertson -

Re·Bus: Issue 1 (Spring 2008) Allegorial Impulses, Edited Iris Balija, Matthew Bowman, Lucy Bradnock and Beth Williamson

re·bus: Issue 1 (Spring 2008) Allegorial Impulses, edited Iris Balija, Matthew Bowman, Lucy Bradnock and Beth Williamson Melancholy and Allegory in Marcel Broodthaers' La Pluie (projet pour un texte), 2 Iris Balija Allegorical Impulses and the Body in Painting, 21 Matthew Bowman Prophet or witness? subverting the allegorical gaze in Francisco Goya's Truth 47 Rescued by Time, Mercedes Cerón The Other Side of the Gaze: Ethnographic Allegory in the Early Films of Maya 73 Deren, John Fox Resisting the Allegorical: Pieter Bruegal's Magpie on the Gallows, 86 Stephanie Porras Allegory and the Critique of the Aesthetic Ideology in Paul de Man, 101 Jeremy Spencer Allegorical Interruptions: Ruined Representation and the work of Ken Jacobs, 123 Francis Summers Contact details School of Philosophy and Art History University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester, Essex CO4 3SQ, UK [email protected] © Iris Balija, 2008 Melancholy and Allegory in Marcel Broodthaers’ La Pluie (projet pour un texte) Iris Balija Abstract Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s notion of the two interpretations of interpretation in Writing and Difference, this paper proposes an allegorical or ‘poetical’ reading of Marcel Broodthaers’ two-minute film of 1969, La Pluie (projet pour un texte). Using the respective examples of Erwin Panofsky and Walter Benjamin’s interpretations of Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencolia I, I argue that although both approaches serve to illuminate Broodthaers’ film, the ambiguity and richness of signification found in the work are best captured by Benjamin’s allegorical method. More than cinema, the new techniques of the image (laser?) offer the way to a solution that is, I fear, momentous, if certainly interesting. -

A Tale of Two Communes

1 A Tale of Two Communes Noel: Ever since I was kid, I’ve been fascinated by communes and collectives. I grew up during the 1980s in a white picket neighborhood in the old north end of Colorado Springs. It was mostly full of professionals and their nuclear families. But there was a secret side of the neighborhood -- a community of lesbians, including my mom, many of whom had kids around my age. And some of them lived together in a commune. It was in a big old victorian house next to a butcher shop called “Babe’s Meat Market.” And it was started by a woman named Bonnie Poucel. Bonnie Poucel: The vision was that we would live, collectively and that we would help each other with our kids, and we would take turns with the work, you know, and that we would contribute financially according to our abilities, you know, and according to what we were making and that- that was the vision. Noel: My mom and I didn’t live there, and she didn’t live with her partner. She was afraid that I could get taken away from her if a nosy neighbor decided to call child welfare... But Bonnie and her kids Jean-Jacques and Genevieve lived there. And my friends Tom and Brooke lived there part-time with their mom. Part of me was glad we didn’t live there. It was like a cross between a sorority house and a hippie grocery store. It was kind of embarrassing in that buttoned down neighborhood. -

(Self-)Reflexivity and Repetition in Documentary

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version UNSPECIFIED UNSPECIFIED Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, UNSPECIFIED. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/87147/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Subjectivity, (Self-)reflexivity and Repetition in Documentary Silke Panse PhD-Thesis 2007 Film Studies School of Drama, Film and the Visual Arts University of Kent Canterbury Abstract This thesis advances a deterritorialised reading of documentary on several levels: firstly, with respect to the difference between non-fiction and fiction, allowing for a fluctuation between both. As this thesis examines the movements of subjective documentary between self-reflexivity and reflexivity, it argues against an understanding of reflexivity as something that is emotionally distanced from its object and thus relies on a strict separation from both the subject and what it documents, such as for instance the stable irony in many found footage or mock-documentaries. -

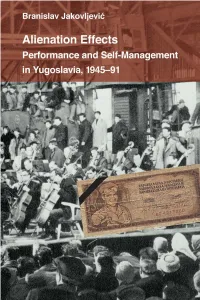

Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia, 1945–91

ALIENATION EFFECTS THEATER: THEORY/TEXT/PERFORMANCE Series Editors: David Krasner, Rebecca Schneider, and Harvey Young Founding Editor: Enoch Brater Recent Titles: Long Suffering: American Endurance Art as Prophetic Witness by Karen Gonzalez Rice Alienation Effects: Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia, 1945–91 by Branislav Jakovljević After Live: Possibility, Potentiality, and the Future of Performance by Daniel Sack Coloring Whiteness: Acts of Critique in Black Performance by Faedra Chatard Carpenter The Captive Stage: Performance and the Proslavery Imagination of the Antebellum North by Douglas A. Jones, Jr. Acts: Theater, Philosophy, and the Performing Self by Tzachi Zamir Simming: Participatory Performance and the Making of Meaning by Scott Magelssen Dark Matter: Invisibility in Drama, Theater, and Performance by Andrew Sofer Passionate Amateurs: Theatre, Communism, and Love by Nicholas Ridout Paul Robeson and the Cold War Performance Complex: Race, Madness, Activism by Tony Perucci The Sarah Siddons Audio Files: Romanticism and the Lost Voice by Judith Pascoe The Problem of the Color[blind]: Racial Transgression and the Politics of Black Performance by Brandi Wilkins Catanese Artaud and His Doubles by Kimberly Jannarone No Safe Spaces: Re-casting Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality in American Theater by Angela C. Pao Embodying Black Experience: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body by Harvey Young Illusive Utopia: Theater, Film, and Everyday Performance in North Korea by Suk-Young Kim Cutting Performances: Collage Events, Feminist Artists, and the American Avant-Garde by James M. Harding Alienation Effects PERFORMANCE AND SELF-MaNAGEMENT IN YUGOSLAVIA, 1945– 91 Branislav Jakovljević ANN ARBOR University of Michigan Press Copyright © 2016 by the University of Michigan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Ifigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Compaoy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 MODERNISM BETWEEN EAST AND WEST: THE HUNGARIAN JOURNAL MA (1916-1925) AND THE INTERNATIONAL AVANT-GARDE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marian Mazzone, B.A., M.A. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title After the 'Post-Sixties': A Cultural History of Utopia in the United States Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/283035c5 Author Lane, Madeline Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ AFTER THE ‘POST-SIXTIES’: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF UTOPIA IN THE UNITED STATES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Madeline Lane March 2016 The Dissertation of Madeline Lane is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Wlad Godzich, chair ____________________________________ Professor Christopher Leigh Connery ____________________________________ Professor Robert Sean Wilson _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………… iv Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………. v Acknowledgments and Dedication ………………………………………………… vi Introduction: Toward a Theory of Utopia at the End of the Post-60s …………….... 1 Part One: Periodizing Anti-Utopianism …………………………………………… 26 Chapter One: Failed Utopia and the Post-60s in Boyle’s Drop City ............ 31 Chapter Two: “There is no use pretending, now”: Reading Le Guin’s 1970s Critical Utopias Against Anti-Utopianism ………………………………… 57 Chapter Three: Finding Utopia in the Dystopian Turn: Punk Literary Utopias in the Long 1980s …………………………………………………………. 81 Part Two: Of Utopia and Recuperation: The Cultural and Spatial Imagination of the American Tech Industry ………………………………………………………….. 130 Chapter Four: “We Owe It All to the Hippies”: Undoing the Post-60s in the Techno-Utopian 1990s …………………………………………………... 136 Chapter Five: False Utopias of Silicon Valley ………………………….. 179 Part Three: Utopia as the Idea of Post-Capitalism ………………………………. -

The New Art Practice in Yugo

Documents 3-6 The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966-1978 Edited by Marijan Susovski Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb 1978 Marijan Susovski Foreword In the last ten years, modern art in Yugoslavia, the fields of reaction on the part of the artists is to achieve spiritual and not artistic interests, the way they develop and manifest themselves materialistic results of creative work, ie. results in which have undergone essential changes in comparison to the forms the artistic quality does not derive solely from the of art which immediately preceded them or still exist. materialized esthetic quality, but in which the artistic Starting from 1966, artists of the new generation, born in the sensibility is expressed in the attitude, behaviour, option, late forties and the early fifties, became involved in artistic way of life in the activities, the acts which can most activities which differed from the established art forms in the adequately express this sensibility. Forced to carry out their milieus in which they lived and worked. New artistic trends activities within a context of art which was inappropriate, developed in Ljubljana, Zagreb, Novi Sad, Subotica, the artists inevitably came into conflict with that which, in Belgrade and Split. The very number of the cities and their their view, represented a hindrance tradition, pedagogic widespread geographical distribution testify to the scope of and art canons, conventions, the institutionalized character of interest in the new approach to artistic communication. The art and with their own social position. They advocated cities represent cultural centres with specific art traditions polemic forms of art, radical changes, analytic and critical which, in some cases, served as the basis for the development artistic activities which should represent an act of social of new trends in art and represented the starting point for relevance. -

Abstract Art Education And

ABSTRACT ART EDUCATION AND STUDENTS WITH EMOTIONAL DISABILITIES: HIGH SCHOOL CASE STUDIES OF POSTMODERN LEARNING, SOCIAL INTERACTION DEVELOPMENT, AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT Kelly Gross, Ph.D. School of Art and Design Northern Illinois University, 2017 Kerry Freedman, Director The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of inclusive postmodern visual arts education for students with ED. The research examines arts learning, social skill interaction development, and general academic achievement. Previous research in the field of special education has focused almost exclusively on behavioral interventions from behaviorist or cognitive approaches for students with ED. Instead, this research focuses on the ability of students to build art skills and change behaviors through constructivist pedagogical approaches. These mixed-methods case studies were implemented over a period of two semesters with four students, four teachers, and two high schools. From the two data sites, seven sets of data were collected: observations, artwork, interviews with students and teachers, GPA, class rank, and graduation status. A mixed-methods case study allowed for investigation into both the individual experience and the larger group experience while addressing the lack of quantitative research on this population in relation to art education. The findings from this study indicate that over time the students in visual arts developed fluency and skills in artmaking, which led to confidence in their work and better peer relationships. The artwork students produced illustrates how they observed, interpreted, and represented themselves through visual media. Data from this research suggest that exposure to art may help students envision other ways of being through learning about their peers and exposure to visual media.