Youth Programs in Remote Central Australian Aboriginal Communities 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

Media Release Wallace Rockhole Wins 2020 Northern Territory Tidy

Media Release Wallace Rockhole wins 2020 Northern Territory Tidy Town Award The proud MacDonnell Regional township of Wallace Rockhole has won the 2020 Northern Territory Tidiest Town Sustainable Community accolade announced today ‘on line’ in Darwin. Northern Territory participating communities were desktop assessed this year due to COVID19 travel uncertainty, restrictions and isolation requirements. Keep Australia Beautiful Council (NT) CEO, Heimo Schober said Wallace Rockhole’s continual dedication and commitment to keeping their community at its best, tidy and beautiful all the time, made it a stand-out again. “The residents living in the harsh beautiful MacDonnell region have embraced the Territory Tidy Towns program for so long, with every community member working together in corporation and collaboration to achieve this well-earned prestigious Award yet again,” Mr Schober said. “The township’s strong pride and culture of continuous improvement and community participation helped the MacDonnell Desert community win the challenging 2020 competition. “The MacDonnell Council Staff, Traditional Owners and the residents of Wallace Rockhole all deserve this win for their efforts and dedication to ensure their community is the Territory’s Tidiest Town and Sustainable Community. “This will be MacDonnell Regional Council’s eight outright win in nine years. It is inspiring to see a Regional Council consistently producing Territory Tidy Town winning communities.” The township of Wallace Rockhole has always demonstrated great community pride and leadership in local sustainability practices and education, and sets a wonderful example for other remote Territory townships to follow. “I congratulate the MacDonnell Regional Council for their support inspiring Wallace Rockhole to win this Award,” Mr Schober added. -

Alice Springs & Macdonnell Ranges Summary-01.Indd

Destination Management Plan Alice Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region 2020 Summary Key Partners 1 Front Cover: Trephina Gorge Nature Park – East MacDonnell Ranges Back Cover: Hermannsburg Potters - Ntaria / Hermannsburg This Page: RT Tours2 Australia - Tjoritja / West MacDonnell National Park Contents Destination Management Plan role and process 5 Alice Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region overview 6 Tourism in the Region Value of tourism in the Region Visitor market profile Trends in regional tourism Destination management planning for the Alice 12 Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Region Guiding principles Destination awareness Approach to developing visitor experiences in the Region Industry gaps and opportunities Action plan 15 Capacity building activities Facilitation of collaborative action Strategic product packaging and marketing Investment attraction initiatives Product development opportunities 19 Implementation 20 Reporting and reviews 22 Acronyms – References – Further information 22 3 Hermannsburg Historic Precinct – Ntaria / Hermannsburg 4 Destination Management Plan role and process The Department of Industry, Destination management requires Tourism and Trade has invested alignment and collaboration across the in destination management public, private and community sectors. It involves stakeholders from both the planning as part of a suite tourism and general industry sectors of actions following the contributing to the development development and release of priority experiences in the Alice of the NT’s Tourism Industry Springs and MacDonnell Ranges Strategy 2030. Destination Region. management ensures that Strategically planned and tourism is cohesively integrated implemented tourism experiences can be an economic driver, contributing into the economic, social, to the growth and development cultural and ecological fabrics of a Region through job creation, of a community, by considering investment attraction, and tourism growth holistically, infrastructure development. -

Aboriginal Interpreter Service

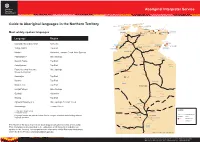

Aboriginal Interpreter Service CROKER ISLAND Guide to Aboriginal languages in the Northern Territory MELVILLE ISLAND Iwaidja GOULBURN ISLANDS BATHURST ISLAND Maung Tiwi ELCHO ISLAND GALIWIN’KU WURRUMIYANGA Ndjebbana MILINGIMBI MANINGRIDA NHULUNBUY DARWIN Burarra Yolngu Matha YIRRKALA Most widely spoken languages GUNBALANYA Kunwinjku RAMINGINING GAPUWIYAK JABIRU Language Region UMBAKUMBA East Side/West Side Kriol Katherine Ngan'gikurrunggurr Nunggubuyu ANGURUGU GROOTE EYLANDT WADEYE East Side Kriol KATHERINE NUMBULWAR Yolngu Matha Top End Anindilyakwa Murrinh Patha NGUKURR West Side Kriol URAPUNGA Warlpiri Katherine, Tennant Creek, Alice Springs HIGHWAY Pitjantjatjara Alice Springs VICTORIA Yanyuwa BORROLOOLA Murrinh Patha Top End Ngarinyman Anindilyakwa Top End Garrwa DAGURAGU Eastern/Central Arrernte, Alice Springs STUART Gurindji Western Arrarnta + KALKARINDJI ELLIOTT Kunwinjku Top End LAJAMANU HIGHWAY Burarra Top End Warumungu Warlpiri BARKLY Modern Tiwi Top End TENNANT CREEK HIGHWAY Luritja/Pintupi Alice Springs Gurindji Katherine ALI CURUNG Alyawarr Maung Top End Alyawarr/Anmatyerr + Alice Springs, Tennant Creek Anmatyerr Warumungu Tennant Creek YUENDUMU Luritja/Pintupi LEGEND Western Desert family PAPUNYA + Arandic family Western Tiwi...................LANGUAGE GROUP Language families are indicated where there is a degree of mutual understanding between Arrarnta ALICE SPRINGS JABIRU .........TOWN language speakers. HERMANNSBURG Eastern/Central Arrernte ELLIOTT ............REMOTE TOWN BARUNGA .........COMMUNITY The Northern Territory -

Federal Budget Submission Using Tourism for Economic Growth in the Centre of Northern Australia 2

FEDERAL BUDGET SUBMISSION USING TOURISM FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE CENTRE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA 2 CONTENTS Overview ..............................................................................................................3 Strategic Plan Infographic ..............................................................................5 Advocacy ..............................................................................................................6 Marketing and Communications ..............................................................14 Visitor Information Services ........................................................................16 Income Development ....................................................................................18 Events..................................................................................................................20 Member Capacity Building ..........................................................................21 Images in this document are subject to copyright. Thank you to Tourism NT for supplying most of the images. 3 Photograph courtesy of David Silva/Tourism NT Tourism Central Australia’s wider operating area OVERVIEW ourism Central Australia is the official Regional Tourism Organisation for the visitor Teconomy in the #RedCentreNT. As a business led organisation, we work in partnership with a wide variety of stakeholders including individuals, businesses and all levels of government, to benefit the visitor economy in the #RedCentreNT. Tourism Central Australia recognises -

NDIS Regional Community Planning Report: Central Australia

September 2018 NDIS Regional Community Planning Report: Central Australia © 2018 PricewaterhouseCoopers. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the Australian member firm, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. At PwC Australia our purpose is to build trust in society and solve important problems. We’re a network of firms in 158 countries with more than 236,000 people who are committed to delivering quality in assurance, tax and advisory services. Find out more and tell us what matters to you by visiting us at www.pwc.com.au Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation Contents Page 1 Introduction Regional Community Planning 5 Contributing PIC Projects 6 2 The Central Australia Region Central Australia Region Communities 8 Central Desert Regional Council Area 9 McDonnell Regional Council Area 11 3 Stakeholder Engagement in Central Australia Community Engagement in Central Australia 15 Stakeholdersconsulted 16 4 Central Australia Service Profile Services available for people with disability 20 Expressed need for services 21 Adjacent services in the Central Australia 22 Central Australia SWOT analysis 23 Stories fromCentral Australia 24 5 Concluding Comments Concluding comments from Central Australia 27 6 Acknowledgements 28 Please note: this document contains images of people. All necessary permissions have been obtained, and our best efforts have been made to ensure it does not contain images of people recently passed, however please be warned that this may be a possibility. -

Review of Certain Fahcsia Funded Youth Services FINAL REPORT

Review of Certain FaHCSIA Funded Youth Services FINAL REPORT Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Canberra August 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Urbis acknowledges the traditional owners, custodians and Elders past and present across Australia. Our thanks also go to the many people who gave their time to speak with us as part of this review, especially those who helped us organise the site visits and welcomed us onto their land and into their services and Natasha Anderson from the Northern Territory Aboriginal Interpreter Service. Ohlin J, Ross S, Wilczynski A, Pigott R, Connell J, Reed-Gilbert K (2010), Review of Certain FaHCSIA- funded youth services , Urbis for the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Canberra. Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements..................................................................................................................................1 1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Overview of the purpose of the review....................................................................................1 1.2 The Integrated Youth Services Project (IYSP)........................................................................1 1.2.1 The activity goals/objectives of the Integrated Youth Services Project...................................2 1.2.2 Integrated Youth Services Program -

Internet on the Outstation: the Digital Divide and Remote Aboriginal Communities

INTERNET ON THE OUTSTATION THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND REMOTE ABORIGINAL COMMUNITIES ELLIE RENNIE, ELEANOR HOGAN, ROBIN GREGORY, ANDREW CROUCH, ALYSON WRIGHT & JULIAN THOMAS A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 19 INTERNET ON THE OUTSTATION THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND REMOTE ABORIGINAL COMMUNITIES ELLIE RENNIE, ELEANOR HOGAN, ROBIN GREGORY, ANDREW CROUCH, ALYSON WRIGHT & JULIAN THOMAS Theory on Demand #19 Internet on the Outstation: The Digital Divide and Remote Aboriginal Communities Authors: Ellie Rennie, Eleanor Hogan, Robin Gregory, Andrew Crouch, Alyson Wright, Julian Thomas Editorial support: Miriam Rasch Cover design: Katja van Stiphout DTP: Léna Robin EPUB development: Léna Robin Printer: Print on Demand Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2016 ISBN: 978-94-92302-07-6 Contact Institute of Network Cultures Phone: +31 20 5951865 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.networkcultures.org This publication is available through various print on demand services. EPUB and PDF editions of this publication are freely downloadable from our website, http://www.networkcultures.org/publications/#tods This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). 3 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Names and Permissions 9 Map 11 Introduction 13 PART I 29 Chapter 1: Policy 31 Chapter 2: Infrastructure 51 PART II 71 Chapter 3: Ownership and Values 73 Chapter 4: Mobility 90 Chapter 5: Uses 98 Chapter 6: Skills and Training 119 -

Tourism Central Australia

8th January 2019 Dear Hon Josh Frydenberg MP, RE: DEVELOPING THE NORTH Prior to Christmas, I wrote to you advising that a budget submission would be forthcoming from Tourism Central Australia. Please find this document attached. Tourism Central Australia (TCA) is a non-profit, innovative membership-based association that assists a wide variety of stakeholders including individuals, businesses and organisations with the growth of the tourism industry in the Red Centre. We service two thirds of the Northern Territory including Alice Springs, the MacDonnell Ranges, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Kings Canyon and the Tennant Creek region, as well as working with our Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Top End counterparts. As you will see, there are significant developments contained in the attached document that, if supported by the Federal Government, will create a surge in economic growth in remote Australia. Northern Australia is at a critical point. Your support, through assisting in the projects listed in this document, will see Northern Australia grow its contribution to GDP. If you have any questions or would like to discuss these projects, please do not hesitate to contact me. Warm regards, Dale McIver Stephen Schwer Chairperson Chief Executive Officer Tourism Central Australia Tourism Central Australia +61 8 8952 5199 +61 8 8952 5199 0417 864 085 0437 091 666 [email protected] [email protected] www.discovercentralaustralia.com www.discovercentralaustralia.com FEDERAL BUDGET SUBMISSION USING TOURISM FOR -

East Macdonnell-Plenty Highway Region VISITOR EXPERIENCE PLAN

East MacDonnell-Plenty Highway Region VISITOR EXPERIENCE PLAN October 2018 Document Register Version Report Date V2.1 Post field visit to Qld end and final community 13092018 meetings at Atitjere & Engawala V3 Final Master Plan 10102018 Acknowledgements This Visitor Experience Plan for the East MacDonnell Ranges and the Plenty Highway region was prepared by TRC Tourism Pty Ltd for the Central Desert Regional Council and its project partners - Tourism Central Australia; the NT Department of Trade, Business & Innovation, and the Department of Tourism and Culture. The Plan was prepared in consultation with the region’s Aboriginal communities, Traditional Owners, other landholders and land managers, and the tourism industry. Disclaimer Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism is not liable to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. Contents 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 2 Current Situation ...................................................................................................................................... 6 3 Vision for the Future .............................................................................................................................. -

Ntaria Artist: Irene Mbitjana Entata Irene Attended the Mission School in Hermannsburg and Later Became a Founding Member of the Hermannsburg Potters

LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN NTARIA Artist: Irene Mbitjana Entata Irene attended the Mission school in Hermannsburg and later became a founding member of The Hermannsburg Potters. She is a dedicated potter, rarely missing a day’s work at the studio though older age is catching up now. Her works are generally centred around her own interpretation of the history of her people over recent generations. Her works depicting mission day life & activity which she calls “Mission Days “ are greatly sought after world wide. The Arrarnta people from Hermannsburg, a former Lutheran mission about 130 km west of Alice Springs, are generally known for their Namatjira-style watercolours. They have a 60 year tradition of producing art. Since 1980, these potters have been producing a vibrant and highly original form of ceramic art that draws on many influences yet strongly reflects the distinctive visual culture of the region. The potters embrace yet reinterpret all these influences and traditions in their own painted ceramics. The artists depict their country as seamless landscapes around the full-bellied forms of the container pots, each of which is guarded by a desert animal or another creature, as the potters say, “from our minds”. Ntaria is the name that has been used to refer to the community in this Local Implementation Plan. While ‘Hermannsburg’ is the official name of the community as listed with the Northern Territory Government Place Names Register, the community has expressed, through consultation with the Single Government Interface and through its Local Reference Group that ‘Ntaria’ is the more appropriate name for use in this Plan. -

Central Desert News

Central Desert News New wheels for Willowra EDITION NO. 29 / MARCH 2016 Aged Care! INSIDE New wheels for Willowra Aged Care! 1 n Friday, 19 February the new aged Ocare bus was delivered to Willowra From the President 2 Aged Care Centre. A small presentation From the CEO 2 took place at the Council Service Welcoming new staff in language 3 Delivery Office presenting the new HiAce commuter bus to the Aged Care Community landscaping with Arid Edge 3 Coordinator and clients. The bus features Fresh harvest in Laramba 4 wheelchair access to enable clients to easily hop on and off. CDP helps reinvent the Wilora Women’s 4 The aged care bus was funded Centre through a partnership between the Aged care gets a windfall 5 Wirliyatjarrayi Aboriginal Land Trust via the Central Land Council, and Central Focus on mediation and justice in Yuendumu 6 Desert Regional Council. CDP build for peace in Yuendumu 6 A painting for the bus was specifically designed by community members for On the Mediation and Justice Program 7 use on the bus. The bus will assist aged Robert Robertson joins the First Circles 7 care to provide activities in and around Program the community, including bush trips, for an aged care facility to be built at Recycling project funds Christmas 8 social activities and visits to the school. Willowra. Once built, this facility will give celebrations This great initiative by the Willowra clients a place to attend for breakfast community represents a strong step Willowra pumping some iron 8 and allow the service to provide cooked forward in developing the aged care meals, showering and blanket washing Yuendumu CDP delivering delicious results 9 service in Willowra.