Medicine Bow Landscape Vegetation Analysis Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinedale Region Angler Newsletter

Wyoming Game and Fish Department 2013 Edition Volume 9 Pinedale Region Angler Newsletter Inside this issue: Burbot Research to Begin in 1 2013 New Fork River Access Im- 2 provements Thanks for reading the 2013 version of Pinedale ND South Dakota Know Your Natives: Northern 3 Region Angler Newsletter. This newsletter is Yellowstone Montana Leatherside intended for everyone interested in the aquatic Natl. Park Sheridan resources in the Pinedale area. The resources we Cody Fire and Fisheries 4 Gillette Idaho manage belong to all of us. Jackson Gannett Peak Wyoming Riverton Nebraska Watercraft Inspections in 2013 6 The Pinedale Region encompasses the Upper Pinedale Casper Green River Drainage (upstream of Fontenelle Lander Elbow Lake 7 Rawlins Reservoir) and parts of the Bear River drainage Green Rock Springs Cheyenne 2013 Calendar 8 near Cokeville (see map). River Laramie Colorado Utah 120 mi Pinedale Region Map Pinedale Region Fisheries Staff: Fisheries Management Burbot Research Begins on the Green River in 2013 Hilda Sexauer Fisheries Supervisor Pete Cavalli Fisheries Biologist Darren Rhea Fisheries Biologist Burbot, also known as “ling”, are a species of fisheries. Adult burbot are a voracious preda- fish in the cod family with a native range that tor and prey almost exclusively on other fish or Aquatic Habitat extends into portions of north-central Wyoming crayfish. Important sport fisheries in Flaming Floyd Roadifer Habitat Biologist including the Wind and Bighorn River drain- Gorge, Fontenelle, and Big Sandy reservoirs ages. While most members of the cod family have seen dramatic changes to some sport fish Spawning reside in the ocean, this specialized fish has and important forage fish communities. -

Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Hunting Seasons

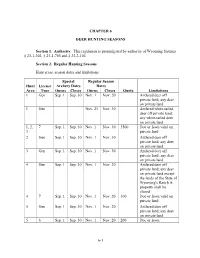

CHAPTER 9 BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOAT HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703, § 23-2-104 and § 23-3-117. Section 2. Definitions. In addition to the definitions set forth in Title 23 of the Wyoming Statutes and Chapter 2, General Hunting Regulation, the Commission also adopts the following definitions for the purpose of this chapter; (a) “Bighorn sheep horns” mean the hollow horn sheaths of male bighorn sheep, either attached to the skull or separated. (b) “Plugging” means placement of a permanent metal plug provided and attached by the Department. Section 3. Bighorn Sheep Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Hunt Archery Dates Season Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 12 Any ram 2 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 20 Any ram 3 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 32 Any ram 4 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 24 Any ram 5 1 Aug. 1 Aug. 31 32 Any sheep valid within the Owl Creek Drainage 5 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 Any ram valid in the entire area 6 1 Aug. 1 Aug. 14 Aug. 15 Oct. 31 1 Any ram (1 resident) 7 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 12 Any bighorn sheep 8 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 7 Any ram (5 residents, 2 nonresidents) 9 1 Aug. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Mineral Occurrence and Development Potential Report Rawlins Resource

CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose of Report ............................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Lands Involved and Record Data ....................................................................................1-2 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF GEOLOGY ...............................................................................................2-1 2.1 Physiography....................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Stratigraphy ......................................................................................................................2-3 2.2.1 Precambrian Era....................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2 Paleozoic Era ........................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.1 Cambrian System...................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.2 Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian Systems ........................................2-5 2.2.2.3 Mississippian System.............................................................................2-5 2.2.2.4 Pennsylvanian System...........................................................................2-5 2.2.2.5 Permian System.....................................................................................2-6 -

Deer Season Subject to the Species Limitation of Their License in the Hunt Area(S) Where Their License Is Valid As Specified in Section 2 of This Chapter

CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Season Hunt License Archery Dates Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on 3 private land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6-1 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep. -

Guide to the Willows of Shoshone National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Willows Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station of Shoshone National General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-83 Forest October 2001 Walter Fertig Stuart Markow Natural Resources Conservation Service Cody Conservation District Abstract Fertig, Walter; Markow, Stuart. 2001. Guide to the willows of Shoshone National Forest. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-83. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 79 p. Correct identification of willow species is an important part of land management. This guide describes the 29 willows that are known to occur on the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. Keys to pistillate catkins and leaf morphology are included with illustrations and plant descriptions. Key words: Salix, willows, Shoshone National Forest, identification The Authors Walter Fertig has been Heritage Botanist with the University of Wyoming’s Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) since 1992. He has conducted rare plant surveys and natural areas inventories throughout Wyoming, with an emphasis on the desert basins of southwest Wyoming and the montane and alpine regions of the Wind River and Absaroka ranges. Fertig is the author of the Wyoming Rare Plant Field Guide, and has written over 100 technical reports on rare plants of the State. Stuart Markow received his Masters Degree in botany from the University of Wyoming in 1993 for his floristic survey of the Targhee National Forest in Idaho and Wyoming. He is currently a Botanical Consultant with a research emphasis on the montane flora of the Greater Yellowstone area and the taxonomy of grasses. Acknowledgments Sincere thanks are extended to Kent Houston and Dave Henry of the Shoshone National Forest for providing Forest Service funding for this project. -

Wind River Expedition Through the Wilderness… a Journey to Holiness July 17-23, 2016

Wind River Expedition Through the Wilderness… a Journey to Holiness July 17-23, 2016 Greetings Mountain Men, John Muir once penned the motivational quote… “The mountains are calling and I must go.” And while I wholeheartedly agree with Muir, I more deeply sense that we are responding to the “Still Small Voice”, the heart of God calling us upward to high places. And when God calls we must answer, for to do so is to embark on an adventure like no other! Through the mountain wilderness Moses, Elijah, and Jesus were all faced with the holiness and power of God. That is our goal and our deepest desire. Pray for nothing short of this my friends and be ready for what God has in store… it’s sure to be awesome! Please read the entire information packet and then follow the simple steps below and get ready! Preparing for the Expedition: Step 1 Now Pay deposit of $100 and submit documents by April 30, 2017 Step 2 Now Begin fitness training! Step 3 Now Begin acquiring gear! (see following list) Step 4 May 31 Pay the balance of expedition $400 Step 5 June 1 Purchase airline ticket (see directions below) Step 6 July 17 Fly to Salt Lake City! (see directions below) Step 7 July 17-23 Wind River Expedition (see itinerary below) Climb On! Marty Miller Blueprint for Men Blueprint for Men, Inc. 2017 © Logistics Application Participant Form - send PDF copy via email to [email protected] Release Form – send PDF copy via email to [email protected] Medical Form – send PDF copy to [email protected] Deposit of $100 – make donation at www.blueprintformen.org Deadline is April 30, 2017 Flight to Denver If you live in the Chattanooga area I recommend that you fly out of Nashville (BNA) or Atlanta (ATL) on Southwest Airlines (2 free big bags!) to Salt Lake City (SLC) on Sun, July 17. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 116, NUMBER 5 Cfjarle* £. anb Jfflarp "^Xaux flKHalcott 3Resiearcf) Jf tmb MIDDLE CAMBRIAN STRATIGRAPHY AND FAUNAS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS (With 34 Plates) BY FRANCO RASETTI The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland SEP Iff 1951 (Publication 4046) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SEPTEMBER 18, 1951 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 116, NUMBER 5 Cfjarie* B. anb Jfflarp "^Taux OTalcott &egearcf) Jf unb MIDDLE CAMBRIAN STRATIGRAPHY AND FAUNAS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS (With 34 Plates) BY FRANCO RASETTI The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland (Publication 4046) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SEPTEMBER 18, 1951 BALTIMORE, MD., U. 8. A. CONTENTS PART I. STRATIGRAPHY Page Introduction i The problem I Acknowledgments 2 Summary of previous work 3 Method of work 7 Description of localities and sections 9 Terminology 9 Bow Lake 11 Hector Creek 13 Slate Mountains 14 Mount Niblock 15 Mount Whyte—Plain of Six Glaciers 17 Ross Lake 20 Mount Bosworth 21 Mount Victoria 22 Cathedral Mountain 23 Popes Peak 24 Eiffel Peak 25 Mount Temple 26 Pinnacle Mountain 28 Mount Schaffer 29 Mount Odaray 31 Park Mountain 33 Mount Field : Kicking Horse Aline 35 Mount Field : Burgess Quarry 37 Mount Stephen 39 General description 39 Monarch Creek IS Monarch Mine 46 North Gully and Fossil Gully 47 Cambrian formations : Lower Cambrian S3 St. Piran sandstone 53 Copper boundary of formation ?3 Peyto limestone member 55 Cambrian formations : Middle Cambrian 56 Mount Whyte formation 56 Type section 56 Lithology and thickness 5& Mount Whyte-Cathedral contact 62 Lake Agnes shale lentil 62 Yoho shale lentil "3 iii iv SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. -

Carbon County DRAFT Natural Resource Management Plan

FEBRUARY 16, 2021 Carbon County DRAFT Natural Resource Management Plan Natural Resource Management Plan Y2 Consultants, LLC & Falen Law Offices (Intentionally Left Blank) Natural Resource Management Plan Y2 Consultants, LLC & Falen Law Offices CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... III LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... VII LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... IX CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................10 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................10 1.2 STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................11 1.3 CARBON COUNTY NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN PROCESS ..............................................15 1.4 CREDIBLE DATA ....................................................................................................................19 CHAPTER 2: CUSTOM AND CULTURE ........................................................................................21 2.1 COUNTY INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ....................................................................................21 2.2 CULTURAL/HERITAGE/PALEONTOLOGICAL -

Glaciers of the Canadian Rockies

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF CANADA GLACIERS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKIES By C. SIMON L. OMMANNEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–J–1 The Rocky Mountains of Canada include four distinct ranges from the U.S. border to northern British Columbia: Border, Continental, Hart, and Muskwa Ranges. They cover about 170,000 km2, are about 150 km wide, and have an estimated glacierized area of 38,613 km2. Mount Robson, at 3,954 m, is the highest peak. Glaciers range in size from ice fields, with major outlet glaciers, to glacierets. Small mountain-type glaciers in cirques, niches, and ice aprons are scattered throughout the ranges. Ice-cored moraines and rock glaciers are also common CONTENTS Page Abstract ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- J199 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------- 199 FIGURE 1. Mountain ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains------------ 201 2. Mountain ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains ------------ 202 3. Oblique aerial photograph of Mount Assiniboine, Banff National Park, Rocky Mountains----------------------------- 203 4. Sketch map showing glaciers of the Canadian Rocky Mountains -------------------------------------------- 204 5. Photograph of the Victoria Glacier, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, in August 1973 -------------------------------------- 209 TABLE 1. Named glaciers of the Rocky Mountains cited in the chapter -

Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 12-30-2020 Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate Allison Reese Trcka Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geomorphology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Trcka, Allison Reese, "Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5637. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate by Allison Reese Trcka A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology Thesis Committee: Andrew G. Fountain Chair Adam Booth Martin Lafrenz Portland State University 2020 Abstract Rock glaciers are flowing geomorphic landforms composed of an ice/debris mixture. A uniform rock glacier classification scheme was created for the western continental US, based on internationally recognized criteria, to merge the various regional published inventories. A total of 2249 rock glaciers (1564 active, 685 inactive) and 7852 features of interest were identified in 10 states (WA, OR, CA, ID, NV, UT, ID, MT, WY, CO, NM). Sulfur Creek rock glacier in Wyoming is the largest active rock glacier (2.39 km2). -

Lakeside Lodge Opportunity Cabins | Restaurant | Bar | Marina PINEDALE, WY

Offering Memorandum For Sale | Investment Lakeside Lodge Opportunity Cabins | Restaurant | Bar | Marina PINEDALE, WY Offered by: John Bushnell 801.947.8300 Colliers International 6550 S Millrock Dr | Suite 200 Salt Lake City, UT 84121 P: +1 801 947 8300 Table of Contents 1. LAKESIDE LODGE RESORT AND MARINA 2. FREMONT LAKE 3. PINEDALE AND SURROUNDING AREA 4. ANNUAL SAILBOAT REGATTA AND FISHING DERBIES 5. ANNUAL MOUNTAIN MAN RENDEZVOUS 6. WIND RIVER AND BRIDGER TETON NATURAL FOREST 7. REGIONAL INFORMATION 8. WEDDINGS AT LAKESIDE 9. INCOME AND PERFORMANCE This document has been prepared by Colliers International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information including, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy and reliability. Any interested party should undertake their own inquiries as to the accuracy of the information. Colliers International excludes unequivocally all inferred or implied terms, conditions and warranties arising out of this document and excludes all liability for loss and damages arising there from. This publication is the copyrighted property of Colliers International and/or its licensor(s). ©2018. All rights reserved. LAKESIDE LODGE | SALE OFFERING COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL P. 3 LAKESIDE LODGE - PINEDALE, WY Lakeside Lodge Resort and Marina ADDRESS: Lakeside Lodge Resort and Marina 99 FS RD 111 Fremont Lake Rd POB 1819 Pinedale, WY 82941 Web Site: www.lakesidelodge.com PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION: Lakeside Lodge is a full service resort located 4 miles north of Pinedale, Wyoming and 75 miles south of Jackson Hole and Teton National Park, Wyoming and 110 miles south of Yellowstone National Park.