Status of Marine Protected Areas in the Mediterranean Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

(Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Temperate Southern Hemisphere: the Genera Nodilittorina, Austrolittorina and Afrolittorina

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2004 Records of the Australian Museum (2004) Vol. 56: 75–122. ISSN 0067-1975 The Subfamily Littorininae (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Temperate Southern Hemisphere: The Genera Nodilittorina, Austrolittorina and Afrolittorina DAVID G. REID* AND SUZANNE T. WILLIAMS Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom [email protected] · [email protected] ABSTRACT. The littorinine gastropods of the temperate southern continents were formerly classified together with tropical species in the large genus Nodilittorina. Recently, molecular data have shown that they belong in three distinct genera, Austrolittorina, Afrolittorina and Nodilittorina, whereas the tropical species are members of a fourth genus, Echinolittorina. Austrolittorina contains 5 species: A. unifasciata in Australia, A. antipodum and A. cincta in New Zealand, and A. fernandezensis and A. araucana in western South America. Afrolittorina contains 4 species: A. africana and A. knysnaensis in southern Africa, and A. praetermissa and A. acutispira in Australia. Nodilittorina is monotypic, containing only the Australian N. pyramidalis. This paper presents the first detailed morphological descriptions of the African and Australasian species of these three southern genera (the eastern Pacific species have been described elsewhere). The species-level taxonomy of several of these has been confused in the past; Afrolittorina africana and A. knysnaensis are here distinguished as separate taxa; Austrolittorina antipodum is a distinct species and not a subspecies of A. unifasciata; Nodilittorina pyramidalis is separated from the tropical Echinolittorina trochoides with similar shell characters. In addition to descriptions of shells, radulae and reproductive anatomy, distribution maps are given, and the ecological literature reviewed. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

The Systematics and Ecology of the Mangrove-Dwelling Littoraria Species (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Indo-Pacific

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Reid, David Gordon (1984) The systematics and ecology of the mangrove-dwelling Littoraria species (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Indo-Pacific. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24120/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24120/ THE SYSTEMATICS AND ECOLOGY OF THE MANGROVE-DWELLING LITTORARIA SPECIES (GASTROPODA: LITTORINIDAE) IN THE INDO-PACIFIC VOLUME I Thesis submitted by David Gordon REID MA (Cantab.) in May 1984 . for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Zoology at James Cook University of North Queensland STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that the following restriction placed by me on access to this thesis will not extend beyond three years from the date on which the thesis is submitted to the University. I wish to place restriction on access to this thesis as follows: Access not to be permitted for a period of 3 years. After this period has elapsed I understand that James Cook. University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All uses consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: 'In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it.' David G. -

The Evolution of Siphonophore Tentilla for Specialized Prey Capture in the Open Ocean

The evolution of siphonophore tentilla for specialized prey capture in the open ocean Alejandro Damian-Serranoa,1, Steven H. D. Haddockb,c, and Casey W. Dunna aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; bResearch Division, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Moss Landing, CA 95039; and cEcology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Edited by Jeremy B. C. Jackson, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, and approved December 11, 2020 (received for review April 7, 2020) Predator specialization has often been considered an evolutionary makes them an ideal system to study the relationships between “dead end” due to the constraints associated with the evolution of functional traits and prey specialization. Like a head of coral, a si- morphological and functional optimizations throughout the organ- phonophore is a colony bearing many feeding polyps (Fig. 1). Each ism. However, in some predators, these changes are localized in sep- feeding polyp has a single tentacle, which branches into a series of arate structures dedicated to prey capture. One of the most extreme tentilla. Like other cnidarians, siphonophores capture prey with cases of this modularity can be observed in siphonophores, a clade of nematocysts, harpoon-like stinging capsules borne within special- pelagic colonial cnidarians that use tentilla (tentacle side branches ized cells known as cnidocytes. Unlike the prey-capture apparatus of armed with nematocysts) exclusively for prey capture. Here we study most other cnidarians, siphonophore tentacles carry their cnidocytes how siphonophore specialists and generalists evolve, and what mor- in extremely complex and organized batteries (3), which are located phological changes are associated with these transitions. -

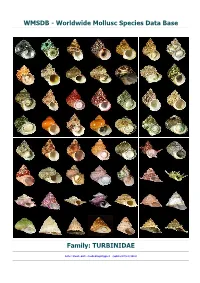

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Biogeographical Homogeneity in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. II

Vol. 19: 75–84, 2013 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online September 4 doi: 10.3354/ab00521 Aquat Biol Biogeographical homogeneity in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. II. Temporal variation in Lebanese bivalve biota Fabio Crocetta1,*, Ghazi Bitar2, Helmut Zibrowius3, Marco Oliverio4 1Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Villa Comunale, 80121, Napoli, Italy 2Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, Lebanese University, Hadath, Lebanon 3Le Corbusier 644, 280 Boulevard Michelet, 13008 Marseille, France 4Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie ‘Charles Darwin’, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Viale dell’Università 32, 00185 Roma, Italy ABSTRACT: Lebanon (eastern Mediterranean Sea) is an area of particular biogeographic signifi- cance for studying the structure of eastern Mediterranean marine biodiversity and its recent changes. Based on literature records and original samples, we review here the knowledge of the Lebanese marine bivalve biota, tracing its changes during the last 170 yr. The updated checklist of bivalves of Lebanon yielded a total of 114 species (96 native and 18 alien taxa), accounting for ca. 26.5% of the known Mediterranean Bivalvia and thus representing a particularly poor fauna. Analysis of the 21 taxa historically described on Lebanese material only yielded 2 available names. Records of 24 species are new for the Lebanese fauna, and Lioberus ligneus is also a new record for the Mediterranean Sea. Comparisons between molluscan records by past (before 1950) and modern (after 1950) authors revealed temporal variations and qualitative modifications of the Lebanese bivalve fauna, mostly affected by the introduction of Erythraean species. The rate of recording of new alien species (evaluated in decades) revealed later first local arrivals (after 1900) than those observed for other eastern Mediterranean shores, while the peak in records in conjunc- tion with our samplings (1991 to 2010) emphasizes the need for increased field work to monitor their arrival and establishment. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Reef Building Mediterranean Vermetid Gastropods: Disentangling the Dendropoma Petraeum Species Complex J

Research Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1333 Zoobank: http://zoobank.org/25FF6F44-EC43-4386-A149-621BA494DBB2 Reef building Mediterranean vermetid gastropods: disentangling the Dendropoma petraeum species complex J. TEMPLADO1, A. RICHTER2 and M. CALVO1 1 Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain 2 Oviedo University, Faculty of Biology, Dep. Biology of Organisms and Systems (Zoology), Catedrático Rodrigo Uría s/n, 33071 Oviedo, Spain Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Marco Oliverio Received: 21 April 2014; Accepted: 3 July 2015; Published on line: 20 January 2016 Abstract A previous molecular study has revealed that the Mediterranean reef-building vermetid gastropod Dendropoma petraeum comprises a complex of at least four cryptic species with non-overlapping ranges. Once specific genetic differences were de- tected, ‘a posteriori’ searching for phenotypic characters has been undertaken to differentiate cryptic species and to formally describe and name them. The name D. petraeum (Monterosato, 1884) should be restricted to the species of this complex dis- tributed around the central Mediterranean (type locality in Sicily). In the present work this taxon is redescribed under the oldest valid name D. cristatum (Biondi, 1857), and a new species belonging to this complex is described, distributed in the western Mediterranean. These descriptions are based on a comparative study focusing on the protoconch, teleoconch, and external and internal anatomy. Morphologically, the two species can be only distinguished on the basis of non-easily visible anatomical features, and by differences in protoconch size and sculpture. -

Sub-Regional Report On

EP United Nations Environment UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG 359/Inf.10 Programme October 2010 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Tenth Meeting of Focal Points for SPAs Marseille, France 17-20 May 2011 Sub-regional report on the “Identification of important ecosystem properties and assessment of ecological status and pressures to the Mediterranean marine and coastal biodiversity in the Adriatic Sea” PNUE CAR/ASP - Tunis, 2011 Note : The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. © 2011 United Nations Environment Programme 2011 Mediterranean Action Plan Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) Boulevard du leader Yasser Arafat B.P.337 – 1080 Tunis Cedex E-mail : [email protected] The original version (English) of this document has been prepared for the Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas by: Bayram ÖZTÜRK , RAC/SPA International consultant With the participation of: Daniel Cebrian. SAP BIO Programme officer (overall co-ordination and review) Atef Limam. RAC/SPA International consultant (overall co-ordination and review) Zamir Dedej, Pellumb Abeshi, Nehat Dragoti (Albania) Branko Vujicak, Tarik Kuposovic (Bosnia ad Herzegovina) Jasminka Radovic, Ivna Vuksic (Croatia) Lovrenc Lipej, Borut Mavric, Robert Turk (Slovenia) CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE ............................................................................................ 1 METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 2 1. CONTEXT ..................................................... ERREUR ! SIGNET NON DÉFINI.4 2. SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE AND AVAILABLE INFORMATION........................ 6 2.1. REFERENCE DOCUMENTS AND AVAILABLE INFORMATION ...................................... 6 2.2. -

Marine Invertebrate Diversity in Aristotle's Zoology

Contributions to Zoology, 76 (2) 103-120 (2007) Marine invertebrate diversity in Aristotle’s zoology Eleni Voultsiadou1, Dimitris Vafi dis2 1 Department of Zoology, School of Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR - 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected]; 2 Department of Ichthyology and Aquatic Environment, School of Agricultural Sciences, Uni- versity of Thessaly, 38446 Nea Ionia, Magnesia, Greece, dvafi [email protected] Key words: Animals in antiquity, Greece, Aegean Sea Abstract Introduction The aim of this paper is to bring to light Aristotle’s knowledge Aristotle was the one who created the idea of a general of marine invertebrate diversity as this has been recorded in his scientifi c investigation of living things. Moreover he works 25 centuries ago, and set it against current knowledge. The created the science of biology and the philosophy of analysis of information derived from a thorough study of his biology, while his animal studies profoundly infl uenced zoological writings revealed 866 records related to animals cur- rently classifi ed as marine invertebrates. These records corre- the origins of modern biology (Lennox, 2001a). His sponded to 94 different animal names or descriptive phrases which biological writings, constituting over 25% of the surviv- were assigned to 85 current marine invertebrate taxa, mostly ing Aristotelian corpus, have happily been the subject (58%) at the species level. A detailed, annotated catalogue of all of an increasing amount of attention lately, since both marine anhaima (a = without, haima = blood) appearing in Ar- philosophers and biologists believe that they might help istotle’s zoological works was constructed and several older in the understanding of other important issues of his confusions were clarifi ed.