The Townland of Nutfield in County Clare1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

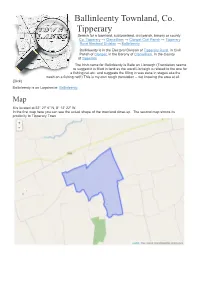

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

County Clare Mary Burke

COUNTY CLARE MARY BURKE Date of Birth/Bap.: 17 Nov., 1869 Place of Birth: Drumcliffe, Ennis, Clare Baptized: 20 Nov, 1869 at Doora Barefield parish, Templemaley, Clare Parents’ Names: Michael Burke & Ellen Higgins Michael worked in Bally Alla. Ellen worked for Capt. Parkinson. Sponsors’ Names: Michael & Margaret Kissane Date of Arrival in US: Not Given Port of Arrival: Not Given Name of Spouse: James Tierney Place of Marriage: Lowell, MA (12 Feb., 1899) Date of Naturalization: Not Given Place of Naturalization: Not Given Occupation in the US: Not Given Date & Place of Death: 22 Jan,1966 at Adams St, Arlington, MA CONTACT INFORMATION Marie Barry [email protected] MARGARET MARY EGAN **1911 photo: Margaret holding John Francis with husband (also) John Francis, daughter Madeline Frances and son Hugh in Brookline, MA Date of Birth/Bap.: 31 Mar., 1873 (Bap. 1 Apr. 1873) Place of Birth: Killulla, Clare Parents’ Names: Pat Egan & Margaret Lahiff Sponsors’ Names: Not Known Date of Arrival in US: Not Given Port of Arrival: Boston, MA Name of Spouse: John Francis O’Hare Place of Marriage: Boston, MA Date of Naturalization: Not Given Place of Naturalization: Not Given Occupation in the US: Worked as a domestic in Newton,MA Date &Place of Death: 27 July, 1942 at Brookline,MA *Margaret was one of 12 children - most of whom immigrated to Boston in the late 1890s. Her oldest sister, Mary, remained in Killulla and married Cornelius Higgins. Mary died 31 Mar., 1931 at Killulla, Clare CONTACT INFORMATION: Janis Duffy [email protected] MARTIN FITZPATRICK Date of Birth/Bap.: 11 Nov., 1865 Place of Birth: Cronagort East, Clare Parents’ Names: Patrick Fitzpatrick & Mary McNamara Sponsors’ Names: Not Known Date of Arrival in US: 1887 Port of Arrival: Boston, MA Name of Spouse: Lizzie Dillon(Dillane) Place of Marriage: Lowell, MA (17 Jan., 1893) Date of Naturalization: Martin was naturalized Place of Naturalization: Not Given Occupation in the US: Worked in mills in Lowell, MA Date &Place of Death: 14 Jan., 1940 at Boston, MA *Martin had 5 known siblings. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

National Famine Commemoration

11 R483 North Clare N67 Kilkee 8 Loop Head Peninsula N68 Ennis (41km) Henr Shanakyle Graveyards 12 10 Back Road Street y Brews T Vandeleur Street Bridge Library Street oler St. Senan’s John Street Town R.C. Church 9 Hall 3 Frances Street 4 Moore Street 7 Maid of Erin National Famine 6 1 Church of 5 Ireland 2 Vandeleur Commemoration Walled Gardens Kilrush Woods Cappa Pier N67 Cappa Village & Killimer (9km) 2013 Playground Design by Edel Butler | Print by Realprint Realprint by | Print Butler Edel Design by 1 Paupers’ Quay 2 Vandeleur Walled Gardens 3 The Quay Mills 4 Market Square 5 Teach Ceoil / Church of Ireland / Kilrush Churchyard 6 To Scattery Island 7 Kilrush Marina 8 Old Workhouse 9 St. Senan’s R.C Church 10 Kilrush Library 11 Kilrush Community Garden 12 Shanakyle Garveyard Maps by OpticNerve.ie Maps by Acknowledge sponsorship received Clare County Council, Kilrush from the Department of Arts, Town Council, Kilrush & District Heritage & Gaeltacht, Kilrush Town Historical Society and the Council, Clare County Council, Department of Arts Heritage Kilrush Credit Union, Shannon and Gaeltacht Affairs wish to Foynes Port Authority, L&M Keating thanks all the individuals and Ltd., Saint Gobain Performance heritage groups who are taking Plastics Ltd., ESB Moneypoint and part in The National Famine Randal B. Counihan & Associates Ltd. Commemoration, Kilrush, 2013. K i l r u s h | Co. Clare | i r e l a n d Illustrated London News Introduction Réamhrá CondiTioN of ireland: illusTraTioNs of The New Poor-law Kilrush, County Clare and its environs were Ba é Cill Rois, agus an ceantar máguaird, i among the areas worst hit by the Great Irish gContae an Chlár ceann de na háiteanna ba Famine between 1845 and the early 1850s. -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

The Earl of Thomond's 1615 Survey of Ibrickan, Co

McInerney Thomond 15/1/14 10:52 AM Page 173 North Munster Antiquarian Journal vol. 53, 2013 173 The Earl of Thomond’s 1615 Survey of Ibrickan, Co. Clare LUKE McINERNEY A transcription and discussion of an early seventeenth century survey of a Co. Clare barony. The chief value of the document is that it represents the earliest rent-roll detailing the Earl of Thomond’s estate in Co. Clare and merits study not least because it is one of the most comprehensive surveys of its type for early seventeenth century Co. Clare. Furthermore, it may be used to ascertain the landholding matrix of Ibrickan and to identify the chief tenants. Presented here is a survey undertaken of the barony of Ibrickan in Co. Clare in 1615.1 The survey covered the entire 63 quarters of the barony. It is lodged at Petworth House archive among the collection of Thomond Papers there.2 At present, our understanding of the changes in landholding for Ibrickan is hindered by the fact that the returns in the 1641 Books of Survey and Distribution3 show that by that time proprietorship of the barony was exclusively in the hands of the Earl of Thomond and few under-tenants are recorded. Having a full list of the chief tenants which dates from the second decade of the seven- teenth century augments our understanding of the changes wrought to landholding, inheritance and social relations in Gaelic regions at a critical juncture in Irish history following the battle of Kinsale. This 1615 survey of part of the extensive estate of the Earl of Thomond serves to focus our gaze at a lower echelon of Gaelic society. -

Download the Guide

YOUR FREE VISITOR GUIDE! The Burren Naturally Yours INSIDE... 4-5 6-7 8-9 The Burren And The Burren: Geosites: Cliffs Of Moher 9 Wonders of Geopark A Rock of Eco the Burren Tourism 10-11 12-13 Burren Living Festivals Towns & Villages & Events 14-15 Cliffs of Moher 16-17 & Doolin Cave Centre of Learning 18-20 21-34 35-48 Food & Drink The Burren Get Active Heaven Perfumery & Glanquin House 58-59 49-57 Burren Places to Ecotourism Stay Members Sandstone and Shale Murrooghtoohy 8 Gleninagh CCastle C ah er Fanore Beach 42 V a l le 2 1 Caher Valley Loop y B Black Head Loop 11 Fanore to Ballyvaughan Trek Fanore R477 Baliny Charging Point C N67 B Gragan C e Trail Head B pair 60-61 62-63 P 43 48 Cahermacnaghten Doolin Cave Craggycorradane tage Trail 26 30 C 24 3 C R477 41 CaherconnellFort Lisdoonvarna C Sustainable L Trail Head The Burren Cycleway B R479 Smokehouse Doolin Pier 17 Dolmen Cycleway R476 y Doolin R Map Cycle Hub Doolin 47 25 33 40 44 Travel R478 G N67 Kilfilfenorae ra CaC thedrala tion Centre Kilfenora r e Cliffs of Moher Kilshanny h o 5 7 12 t M Visitor Experience 35 R f R481 o s 27 34 ff li C 21 H 1 2 2 Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors canno t be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. -

Polling Scheme 2016

COMHAIRLE CONTAE AN CHLÁIR CLARE COUNTY COUNCIL POLLING SCHEME SCÉIM VÓTÁLA Acht Toghcháin 1992 Acht Toghcháin (Leasú) 2001 Na Rialachàin (Scéimeanna Vótàla) 2005 Electoral Act 1992 Electoral (Amendment) Act 2001 Electoral (Polling Schemes) Regulations 2005 th 12 September 2016 THIS POLLING SCHEME WILL APPLY TO DÁIL, PRESIDENTIAL, EUROPEAN, LOCAL ELECTIONS AND ALSO TO REFERENDA All Electoral Areas in County Clare included in this document: Ennis Killaloe Shannon West Clare Constituency of Clare Constituency of Limerick City (Part of) ********************************** 2 Clare County Council Polling Scheme Electoral Act 1992 and Polling Scheme Regulations 2005 Introduction A Polling Scheme divides a County into Electoral Areas and these are further broken down in to Polling Districts, Electoral Divisions, and Townlands. The Scheme sets out a Polling Place or Polling Station for the townlands for electoral purposes. The Register of Electors is then produced in accordance with the districts defined within the Scheme. The making of a Polling Scheme is a reserved function of the Elected Members of the Council. County Clare consists of Two Dàil Constituencies, which are where the voters in County Clare democratically elect members to Dáil Éireann : 1. Constituency of Clare and the 2. Part of the Constituency of Limerick City County Clare now consists of four Electoral Areas which were set up under the Local Electoral areas and Municipal Districts Order 2014 Ennis Killaloe Shannon West Clare. 3 INDEX FOR POLLING SCHEME Constituencies Pages Constituency -

Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork

Published by the Stationery Office, Dublin, Ireland. To be purchased from the: Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork. Government Publications Sales Office, Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2, or through any bookseller. Prn 443. Price 15.00. July 2003. © Government of Ireland 2003 Material compiled and presented by Central Statistics Office. Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. ISBN 0-7557-1507-1 3 Table of Contents General Details Page Introduction 5 Coverage of the Census 5 Conduct of the Census 5 Production of Results 5 Publication of Results 6 Maps Percentage change in the population of Electoral Divisions, 1996-2002 8 Population density of Electoral Divisions, 2002 9 Tables Table No. 1 Population of each Province, County and City and actual and percentage change, 1996-2002 13 2 Population of each Province and County as constituted at each census since 1841 14 3 Persons, males and females in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas of each Province, County and City and percentage of population in the Aggregate Town Area, 2002 19 4 Persons, males and females in each Regional Authority Area, showing those in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas and percentage of total population in towns of various sizes, 2002 20 5 Population of Towns ordered by County and size, 1996 and 2002 21 6 Population and area of each Province, County, City, urban area, rural area and Electoral Division, 1996 and 2002 58 7 Persons in each town of 1,500 population and over, distinguishing those within legally defined boundaries and in suburbs or environs, 1996 and 2002 119 8 Persons, males and females in each Constituency, as defined in the Electoral (Amendment) (No. -

![Documents from the Thomond Papers at Petworth House Archive1 [With Index]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5624/documents-from-the-thomond-papers-at-petworth-house-archive1-with-index-1035624.webp)

Documents from the Thomond Papers at Petworth House Archive1 [With Index]

Luke McInerney Documents from the Thomond Papers at Petworth House Archive1 [with index] The Petworth House Archive (PHA) is an important and under-exploited repository for research into seventeenth and eighteenth-century Co. Clare. Petworth House, the historic seat of the earls of Egremont, holds primary source material relating to the estates of the earls of Thomond in North Munster, chiefly for Co. Clare but also Co. Limerick and Co. Tipperary. The material preserved at Petworth contains a range of material includ- ing estate management documentation, correspondence, accounts, legal papers, military, parliamentary papers, family history, maps and surveys.2 Only a small proportion of the tens of thousands of documents in the archive relate to the earls of Thomond’s Irish estates and the surviving ‘Thomond papers’ probably represent only a fraction of the original col- lection, loss and damage having taken its toll. Not all of the Thomond material is listed in the current Petworth catalogue; a large portion of the material is still available only in an unpublished early nineteenth-century manuscript catalogue. For historians of Gaelic Ireland the Thomond papers are notewor- thy as they contain detail on landholding at different social levels; key legal instruments such as inquisitions post mortem of Connor O’Brien (1581) third earl of Thomond, and Donough O’Brien (1624) fourth earl of Thomond, are preserved in the archive, along with petitions and leases of Gaelic freeholders. Freeholders of sept-lineages petitioned for restoration of their lands as they were increasingly disenfranchised in the new land- holding matrix of seventeenth century Co. -

Recorded Monuments County Clare

Recorded Monuments Protected under Section 12 of the Notional Monuments (Amendment) Act, 1994 County Clare DdchasThe Heritage Service Departmentof The Environment, Heritage and Local Govemment 1998 RECORD OF MONUMENTSAND PLACES as Established under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment) Act 1994 COUNTY CLARE Issued By National Monumentsand Historic Properties Service 1996 Establishment and Exhibition of Record of Monumentsand Places under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment) Act 1994 Section 12 (1) of the National Monuments(Amendment) Act 1994 states the Commissionersof Public Worksin Ireland "shall establish and maintain a record of monumentsand places where they believe there are monumentsand the record shall be comprised of a list of monuments and such places and a map or maps showing each monument and such place in respect of each county in the State. " Section 12 (2) of the Act provides for the exhibition in each county of the list and maps for that county in a manner prescribed by regulations made by the Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht. The relevant regulations were made under Statutory Instrument No. 341 of 1994, entitled National Monuments(Exhibition of Record of Monuments) Regulations, 1994. This manualcontains the list of monumentsand places recorded under Section 12 (1) of the Act for the Countyof Clare whichis exhibited along with the set of mapsfor the County of Clare showingthe recorded monumentsand places. 0 Protection of Monumentsand Places included in the Record Section 12 (3) of the -

East Burren Complex SAC

SITE SYNOPSIS Site Name: East Burren Complex SAC Site Code: 001926 This large site incorporates all of the high ground in the east Burren in Counties Clare and Galway, and extends south-eastwards to include a complex of calcareous wetlands. The area encompasses a range of limestone habitats that include limestone pavement and associated calcareous grasslands and heath, scrub and woodland together with a network of calcareous lakes and turloughs. The site exhibits some of the best and most extensive areas of oligotrophic limestone wetlands to be found in the Burren and in Europe. The site is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) selected for the following habitats and/or species listed on Annex I / II of the E.U. Habitats Directive (* = priority; numbers in brackets are Natura 2000 codes): [3140] Hard Water Lakes [3180] Turloughs* [3260] Floating River Vegetation [4060] Alpine and Subalpine Heaths [5130] Juniper Scrub [6130] Calaminarian Grassland [6210] Orchid-rich Calcareous Grassland* [6510] Lowland Hay Meadows [7210] Cladium Fens* [7220] Petrifying Springs* [7230] Alkaline Fens [8240] Limestone Pavement* [8310] Caves [91E0] Alluvial Forests* [1065] Marsh Fritillary (Euphydryas aurinia) [1303] Lesser Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) [1355] Otter (Lutra lutra) The limestone pavement at this site includes smooth blocky and shattered types. The bare pavement is interspersed with species-rich calcareous vegetation communities. Typical grassland species found on or near the pavement include Blue Moor-grass (Sesleria albicans), Mountain Everlasting (Antennaria dioica), Bloody Crane’s-bill (Geranium sanguineum) and Wild Thyme (Thymus praecox). Where soil cover is more Version date: 9.2.2016 1 of 5 001926_Rev16.Docx extensive purer grassland communities are found, and these are often orchid-rich.