Working Paper Nº 10/09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basque Experience with the Irish Model

WORKING PAPERS IN CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSN 2053-0129 (Online) From Belfast to Bilbao: The Basque Experience with the Irish Model Eileen Paquette Jack, PhD Candidate School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University, Belfast [email protected] Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice CTSJ WP 06-15 April 2015 Page | 1 Abstract This paper examines the izquierda Abertzale (Basque Nationalist Left) experience of the Irish model. Drawing upon conflict transformation scholars, the paper works to determine if the Irish model serves as a tool of conflict transformation. Using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the paper argues that it is a tool, and focuses on the specific finding that it is one of many learning tools in the international sphere. It suggests that this theme can be generalized and could be found in other case studies. The paper is located within the discipline of peace and conflict studies, but uses a method from psychology. Keywords: Conflict transformation, Basque Country, Irish model, Peace Studies Introduction1 The conflict in the Basque Country remains one of the most intractable conflicts, and until recently was the only conflict within European borders. Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) has waged an open, violent conflict against the Spanish state, with periodic ceasefires and attempts for peace. Despite key differences in contexts, the izquierda Abertzale (‘nationalist left’) has viewed the Irish model – defined in this paper as a process of transformation which encompasses both the Good Friday Agreement (from here on referred to as GFA) and wider peace process in Northern Ireland – with potential. -

Assessing ETA's Strategies of Terrorism

Small Wars & Insurgencies ISSN: 0959-2318 (Print) 1743-9558 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fswi20 End of the cycle: assessing ETA’s strategies of terrorism Charles W. Mahoney To cite this article: Charles W. Mahoney (2018) End of the cycle: assessing ETA’s strategies of terrorism, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29:5-6, 916-940 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1519300 Published online: 07 Mar 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fswi20 SMALL WARS & INSURGENCIES 2018, VOL. 29, NOS. 5–6, 916–940 https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1519300 End of the cycle: assessing ETA’s strategies of terrorism Charles W. Mahoney Department of Political Science, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA ABSTRACT In May 2018, the Basque insurgent group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) officially disbanded after a 60-year struggle. This inquiry assesses ETA’s violent cam- paigns using recent conceptual and theoretical advancements from the field of terrorism studies. Three conclusions concerning the group’s strategies of terrorism are advanced. First, ETA regularly targeted civilians to achieve goals other than coercing the Government of Spain; these objectives included out- bidding rival separatist groups and spoiling negotiation processes. Second, ETA’s most rapid period of organizational growth occurred as the result of an aggressive terrorist campaign, demonstrating that civilian targeting can serve as a stimulus to rebel group recruitment. Finally, while terrorism did not advance ETA’s primary political objective of creating an independent Basque state, it did enable the group to assume a leading position within the radical Basque separatist movement, helping extend ETA’s lifespan and making the group an embedded actor within the contentious political processes surround- ing the question of Basque self-determination. -

ETA and the Public, 1959-1987

ETA and the Public McCreanor ETA and the Public, 1959-1987 KYLE McCREANOR1 After an ephemeral moment of autonomy during the Spanish Civil War, the Basque Country was conquered by Spanish Nationalist forces. Under the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, the Basque people were subject to heavy oppression. The Francoist state sought to eliminate the Basque language and culture as part of a grand vision to create a ‘unified Spain.’ In 1959, a Basque guerrilla resistance movement, Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA: Basque Country and Freedom) was born with a mission to preserve their unique language and culture, and ultimately, to secure an independent Basque state. Their initial strategy was to incite a revolution by symbolic acts of violence against the Franco regime and gain popular support in the Basque Country. This paper explores ETA’s relationship with the public, analyzing the ways in which they cultivated support and disseminated their ideas to the masses. However, what the research finds is that as ETA’s strategy changed, so did their relationship with the public. After Spain’s democratization, ETA abandoned the idea of bringing about a revolution of the masses, and sought only to wage a violent war of attrition against the Spanish state in order to establish a sovereign Basque nation. The Basque Country, or Euskadi, is a region straddling the Northern Pyrenees, falling under the jurisdiction of Spain and France. It is the homeland of the Basque people, an ancient 1 This research paper was made possible by a Directed Reading course in the Department of History, supervised by Professor Matthew Koch. -

Multilevel Electoral Competition: Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository Multilevel Electoral Competition: Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain Francesc Pallarés and Michael Keating Abstract Regionalisation in the form of the creation of Autonomous Communities (ACs) has played a significant role in shaping the Spanish party system since the transition to democracy in 1977. Parties are divided into state-wide parties, operating at both national and regional levels, and non state-wide parties. The latter are most important in the historic nations of Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia. Autonomous elections are generally second order elections, with lower turnout and with results generally following the national pattern. In certain cases, the presence of non-state wide parties challenges this pattern and in Catalonia a distinct political arena exists with its own characteristics. Autonomous parliaments and governments have provided new opportunities for both state-wide and non-state-wide parties and served as a power base for political figures within the parties. 2 Introduction The reconfiguration of Spain as an Estado de las autonomías (state of the autonomies) has produced multiple arenas for political competition, strategic opportunities for political actors, and possibilities for tactical voting. We ask how the regional level fits into this pattern of multilevel competition; what incentives this provides for the use of party resources; how regionalisation has affected the development of political parties; how these define their strategies in relation to the different levels of party activity and of government; how these are perceived by electors and affect electoral behaviour; and whether there are systematic differences in electoral behaviour at state and regional levels. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Intractability of the Basque Conflict

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE INTRACTABILITY OF THE BASQUE CONFLICT A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Graham M. Stubbs, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 2012 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE INTRACTABILITY OF THE BASQUE CONFLICT Graham M. Stubbs B.A. Joseph P. Smaldone Phd. ABSTRACT Since the regime of dictator General Franco (1939-1975), the Spanish government has repressed or banned virtually all expressions of the Basque national identity and political expression. This failure to recognize the Basque culture within Spanish society has created a void in which the Basques have felt self-confined for generations. The conflict between the Basques and Spain has never found clear resolution, has often been punctuated by armed resistance, and has become virtually intractable. Spanish nationalism has prevailed over the indigenous group in the region, leaving resentment and frustration for those seeking to practice their traditions and cultural distinctions. The Spanish blend of fascist, traditionalist, and militarist responses has reinforced the deep- felt resentment of the Basque people in their pursuit of the civil liberties granted to all other citizens of the Spanish state. The existence of the Basques has been problematic to the Spanish because cultural differences challenged Franco’s ideal of a unified Catholic state. Catholicism was the essence of the ‘nation’ and Castile was its ‘ethnic core,’ thus leaving little room for any opposing ideology and principles. -

The Europhile Fringe?

European Union Politics The Europhile Fringe? DOI: 10.1177/1465116507073290 Volume 8 (1): 109–130 Regionalist Party Support for European Copyright© 2007 Integration SAGE Publications Los Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore Seth Kincaid Jolly University of Chicago, USA A B S T R A C T The relationship between European integration and regionalist parties is still a largely unexplored area of research. In this paper, I evaluate whether regionalist parties perceive the European Union (EU) as an ally or an enemy. Using expert surveys, I assess the views of regionalist parties on European integration and I find that regionalist political parties are consistently pro-EU across time, space, and issue area. I find further support for this finding in a case study of the Scottish National Party. K E Y W O R D S Euroskepticism multi-level governance regionalist parties 1 0 9 Downloaded from http://eup.sagepub.com at CHICAGO UNIVERSITY on February 28, 2007 © 2007 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. 1 1 0 European Union Politics 8(1) In a Europe characterized by multi-level governance, regionalist political parties can frame the European Union (EU) either as an ally against the central state or as yet another foreign power threatening local autonomy. In one line of reasoning, European integration decreases the necessity for traditional large states, making smaller, more homogeneous states more viable (Alesina and Spolaore, 2003). Hence, the EU may be an unwitting ally of subnational groups against central governments, thereby encouraging regionalist parties to be Europhiles. On the other hand, regional political entrepreneurs may exploit fear of yet another foreign authority encroaching on local sovereignty or xenophobia to convince voters to leave mainstream parties and support alternative parties. -

ETA and State Action: the Development of Spanish Antiterrorism

ETA and state action: The development of Spanish antiterrorism *** Cite this article: Ubasart-González, G. ETA and state action: the development of Spanish antiterrorism. Crime Law Soc Change 72, 569–586 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611- 019-09845-6. *** ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT VERSION. The final publication is available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10611-019-09845-6 Abstract On 20 October 2011 ETA announced the ‘definitive cessation of its armed activity’, which had been increasing since shortly after its inception in 1959. On 8 April 2017 it disarmed by handing over its weapons to intermediaries from civil society. On 2 May 2018 ETA announced its dissolution. This was the end of the last ongoing armed conflict in Europe from the wave of political violence – linked to national and class disputes – that swept over the continent starting in the 1960s. This article analyses the development of Spanish antiterrorism in relation to the Basque conflict, observing how a free and democratic Spanish state has responded to the challenge of an armed insurgency that has continued to the present. While the history of the organisation is well known, less so is the development of the reaction to deal with it. ETA’s progression cannot be understood in isolation, but rather needs to be placed into the context of the measures taken by the state, which influenced, shaped, and was shaped by it throughout the course of the conflict. Keywords: ETA, terrorism, antiterrorism, the culture of emergency, the Basque Country, peace process Introduction On 20 October 2011 Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) announced the ‘definitive cessation of its armed activity’, which had been increasing since shortly after its inception. -

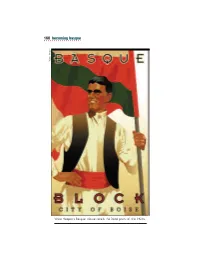

11Reclaiming the FLAG by Kyle Eidson with Dave Lachiondo

168 becoming basque reclaiming the flag 169 r e p o o H d r a W 11Reclaiming the FLAG by Kyle Eidson with Dave Lachiondo n December 1970, 16 members of the Basque separatist group ETA, the acronym for Basque Homeland and Liberty, were charged with the mur - der of a Spanish police commissioner. The Burgos 16, court-martialed I and found guilty, had little or no access to attorneys. Six of the accused were sentenced to death by firing squad. The case drew global notori - ety, calling attention to the larger issues of independence for the Basque Country and the disregard for civil liberties and human rights under the rule of General Francisco Franco. In Idaho, many Basques protested, urging the commutation of Franco’s sentences. For many Boise Basques, this was the latest chapter in a centuries-old cycle of repression and cultural subjugation. The Basque Country ( Euskal Herria ) today is a region with three lan - guages, two sovereign states and seven provinces. Approximately three mil - lion people make the region their home, most of whom live in Spain, with the remainder in France. Since the Middle Ages, French and Spanish kings agreed to a set of laws ( foruak ) that gave the Basques local control over tax - Ward Hooper’s Basque tribute recalls the Deco prints of the 1920s. 168 becoming basque reclaiming the flag 169 r e p o o H d r a W 11Reclaiming the FLAG by Kyle Eidson with Dave Lachiondo n December 1970, 16 members of the Basque separatist group ETA, the acronym for Basque Homeland and Liberty, were charged with the mur - der of a Spanish police commissioner. -

The ETA: Spain Fights Europe's Last Active Terrorist Group

The ETA: Spain Fights Europe’s Last Active Terrorist Group William S. Shepard One week after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pen- tagon on 11 September 2001, President George W. Bush marshaled the American people and allies of good will everywhere to a new course through his speech to Congress. In it, he resolutely condemned the attacks and promised sustained retribution. “It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated,” he announced. The world knows that he was speaking of Osama bin Laden and his al Qaeda network, but shortly thereafter, media commentators posed the ques- tion whether all nations on the list that the United States says sponsor ter- rorism, including Iraq, Iran, Sudan, and Syria, were potential targets. Others wondered whether all organizations that the United States has officially con- demned as terrorist, including Shining Path in Peru and the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) in Spain and France, were included in the president’s announcement.1 The ETA had again been designated a foreign terrorist organization by the secretary of state on 5 October 2001. One way to move away from the terrorist label is to negotiate. It may be coincidental, but it struck me that on 26 September, just two weeks after the attacks, Palestinian chairman Yasser Arafat sat down for preliminary talks with Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres. Furthermore, at least one well- known group took quick pains to disassociate itself from America’s potential 1. Sally Buzbee, “Nations Debate Who Terrorists Are,” Associated Press, 23 September 2001. -

CASE of HERRI BATASUNA and BATASUNA V. SPAIN

FIFTH SECTION CASE OF HERRI BATASUNA AND BATASUNA v. SPAIN (Applications nos. 25803/04 and 25817/04) JUDGMENT STRASBOURG 30 June 2009 FINAL 06/11/2009 This judgment has become final under Article 44 § 2 of the Convention. HERRI BATASUNA AND BATASUNA v. SPAIN JUDGMENT 1 In the case of Herri Batasuna and Batasuna v. Spain, The European Court of Human Rights (Fifth Section), sitting as a Chamber composed of: Peer Lorenzen, President, Rait Maruste, Karel Jungwiert, Renate Jaeger, Mark Villiger, Isabelle Berro-Lefèvre, judges, Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz, ad hoc judge, and Claudia Westerdiek, Section Registrar, Having deliberated in private on 23 June 2009, Delivers the following judgment, which was adopted on that date: PROCEDURE 1. The case originated in two applications (nos. 25803/04 and 25817/04) against the Kingdom of Spain lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (“the Convention”) by two political parties, Herri Batasuna and Batasuna (“the applicant parties”), on 19 July 2004. 2. The applicant parties were represented before the Court by Mr D. Rouget, a lawyer practising in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. The Spanish Government (“the Government”) were represented by their Agent, Mr I. Blasco, Head of the Legal Department for Human Rights, Ministry of Justice. 3. Relying on Articles 10 and 11 of the Convention, the applicant parties alleged, in particular, that their dissolution had entailed a violation of their right to freedom of expression and of their right to freedom of association. They complained that Institutional Law no. 6/2002 on political parties (Ley Orgánica 6/2002 de Partidos Políticos – “the LOPP”) of 27 June 2002, which they described as an ad hoc law, was neither accessible nor foreseeable, had been applied retrospectively and that their dissolution had pursued no legitimate aim but had been intended, in their view, to silence any debate and to deprive them of their freedom of expression. -

Basque Nationalism and Its Actors: Origins and Developments

Cattedra RELATORE CANDIDATO Anno Accademico Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………2 Chapter One: Three tenets of Basque nationalism….……………………………………………3 1.1 Geography of the Basque Country……………………………………………………………….3 1.2 The Basque Language……………………………………………………………………………5 1.3 A historiographical overview…………………………………………………………………….8 Chapter Two: non-electoral Basque nationalist actors….………….………………………...…13 2.1 Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA) until 1975…………..…………………………………………….13 2.2 Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA) after 1975………………………………………………………...15 Chapter Three: Electoral Basque nationalist actors……………………………………………..18 3.1 The Basque Nationalist Party (PNV)…………………………………………………………….18 3.2 The Abertzale Left………………………………………………………………………………21 3.3 Recent electoral history of Basque nationalist parties…………………………………………...23 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….…28 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………..30 Riassunto in lingua italiana………………………………………………………………………..32 1 Introduction This analysis will focus on Basque nationalism and its actors in order to come to a better understanding of the processes that started, transformed and modernised such ideology. The dissertation will start by introducing in the first Chapter the three core tenets to Basque nationalism: its peculiar geography, which represents a nation being divided in two parts at the grey Atlantic periphery of two modern states; its language, so complex and unintelligible to any non- Basque because of its unique status of language isolate; its history, witness of turbulent aspirations and discrimination. Later on, Chapter two will analyse the most infamous non-electoral political actor of Basque nationalism: ETA. By focusing on its history and its actions, it will be possible to realise their impact in modern Basque and Spanish politics. Finally, the last Chapter will be devoted to the study of two electoral actors of Basque nationalism: the Basque Nationalist Party and the Patriotic Left. -

Violence and Political Institutions in the Basque Country Albert Padró-Solanet UOC-IN3 Apadro [email protected]

Violence and Political Institutions in the Basque Country Albert Padró-Solanet UOC-IN3 [email protected] Paper prepared for presentation at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, St. Gallen, Switzerland. Workshop: Political institutions and political violence. Directors: Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, & Simon Hug. Preliminary draft. Not for quotation Introduction A credible analysis or proposal to solve the problem of the treatment of violence in divided societies has to based in a good understanding of the micro-foundations of the political mobilization in these societies. Much of the engineering models seem to have been based on rather strong simplifications of the electoral behaviour of the citizens. This paper aims to contribute to the understanding of the underlying political competition in divided societies with a neo-downsian model of party competition that is based on the interpretation of Tsebelis (1991) of the consocionalism. According to the degree of monopoly control of the representation in each segment, the political elite can easily undertake the accommodation politics. If the political preferences of each segment of a divided society can be represented in a single dimension, the monopolistic elite can choose any point of the space. If the political market is sufficiently open (i.e. there are no strong institutional barriers to representation) and the national issue becomes salient, the elite has to take into account the position of potential or actual rivals. This situation seems to introduce more polarization and destabilization in the political system. This increase of the polarization is related to the phenomenon of outbidding, a typical problem of political competition in divided societies.