Script and Links As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH

UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus Undergraduate 2012 Entry 2012 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry www.ed.ac.uk EDINB E56 UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 3 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 1 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Welcome to the University of Edinburgh We’ve been influencing the world since 1583. We can help influence your future. Follow us on www.twitter.com/UniofEdinburgh or watch us on www.youtube.com/user/EdinburghUniversity UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 3 The University of Edinburgh Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry Welcome www.ed.ac.uk 3 Welcome Welcome Contents Contents Why choose the University of Edinburgh?..... 4 Humanities & Our story.....................................................................5 An education for life....................................................6 Social Science Edinburgh College of Art.............................................8 pages 36–127 Learning resources...................................................... 9 Supporting you..........................................................10 Social life...................................................................12 Medicine & A city for adventure.................................................. 14 Veterinary Medicine Active life.................................................................. 16 Accommodation....................................................... 20 pages 128–143 Visiting the University............................................... -

Belmond Directory

BELMOND WELCOMES THE WORLD 2 LANDMARK HOTELS 4 GREAT TRAIN JOURNEYS 6 PIONEERING RIVER CRUISES 8 “HAPPINESS IS NOT A GOAL — IT’S A BY-PRODUCT OF A LIFE WELL-LIVED” ELEANOR ROOSEVELT 10 HOTELS ST. PETERSBURG TRAINS EDINBURGH DUBLIN MANCHESTER RIVER CRUISES OXFORDSHIRE LONDON PARIS BURGUNDY VENICE PORTOFINO FLORENCE RAVELLO NEW YORK MALLORCA NORTH AMERICA 14 – 29 TAORMINA ST MICHAELS SOUTH AMERICA 30 – 49 SANTA MADEIRA CHARLESTON BARBARA EUROPE 50 – 85 AFRICA 86 – 91 ASIA 92 – 109 SAN MIGUEL DE RIVIERA AYEYARWADY RIVER ALLENDE MAYA ST MARTIN CHINDWIN RIVER LUANG YANGON PRABANG BANGKOK SIEM REAP KOH SAMUI MACHU PICCHU SACRED VALLEY JIMBARAN LIMA CUSCO AREQUIPA LAKE TITICACA RIO DE MOREMI RESERVE JANEIRO CHOBE NATIONAL IGUASSU OKAVANGO DELTA PARK FALLS 12 CAPE TOWN 13 NORTH AMERICA GLAMOROUS HOTELS, RESORTS AND RESTAURANTS IN THE USA, MEXICO AND THE CARIBBEAN. 14 THE RESORT’S STYLISH SUITES, VILLAS AND RESTAURANTS HAVE BEEN BEAUTIFULLY DESIGNED TO OPEN UP FRESH OCEAN VISTAS AND LET THE LIGHT FLOOD IN. 83 SUITES AND ROOMS, 8 THREE- AND FOUR- BEDROOM VILLAS • TWO RESTAURANTS, BAR Beside the island’s most spectacular sweep AND BEACH BAR, WINE CELLAR • LA SAMANNA SPA, FITNESS CENTER, 3 TENNIS COURTS, of sand, where France meets the Caribbean 2 SWIMMING POOLS • WATERSPORTS, BEACH CABANAS, PRIVATE BOAT • THE RENDEZVOUS PAVILION FOR MEETINGS • 5KM FROM MARIGOT 16 BELMOND LA SAMANNA PO BOX 4077, 97064 ST MARTIN, CEDEX, FRENCH WEST INDIES TEL: +590 590 87 6400 (FRENCH CAPITAL) AND FROM JULIANA AIRPORT 17 63 SUITES AND ROOMS • GASTRONOMIC DINING AND BAR, BEACH RESTAURANT, TEQUILA AND CEVICHE BAR • AWARD- WINNING KINAN SPA, WATERSPORTS, INCLUDING CAVE DIVING • 3 POOLS, 2 TENNIS COURTS • SPACES FOR WEDDINGS, MEETINGS AND CONFERENCES • CULTURAL TOURS, CHILDREN’S PROGRAMME • 40KM FROM CANCÚN TALCUM-WHITE SANDS STRETCH INTO THE DISTANCE ON WHAT HAS BEEN VOTED ONE OF THE WORLD’S FINEST BEACHES— THE ULTIMATE RETREAT IN WHICH TO RELAX, SIP TEQUILA AND DINE. -

'Women in Medicine & Scottish Women's Hospitals'

WWI: Women in Medicine KS3 / LESSONS 1-5 WORKSHEETS IN ASSOCIATION WITH LESSON 2: WORKSHEET Elsie Ingis 1864 – 1917 Elsie Inglis was born in 1864, in the small Indian town of Naini Tal, before moving back to Scotland with her parents. At the time of her birth, women were not considered equal to men; many parents hoped to have a son rather than a daughter. But Elsie was lucky – her mother and father valued her future and education as much as any boy’s. After studying in Paris and Edinburgh, she went on to study medicine and become a qualified surgeon. Whilst working at hospitals in Scotland, Elsie was shocked to discover how poor the care provided to poorer female patients was. She knew this was not right, so set up a tiny hospital in Edinburgh just for women, often not accepting payment. Disgusted by what she had seen, Elsie joined the women’s suffrage campaign in 1900, and campaigned for women’s rights all across Scotland, with some success. In August 1914, the suffrage campaign was suspended, with all efforts redirected towards war. But the prejudices of Edwardian Britain were hard to break. When Elsie offered to take an all-female medical unit to the front in 1914, the War Office told her: “My good lady, go home and sit still.” But Elsie refused to sit still. She offered help to France, Belgium and Serbia instead – and in November 1914 dispatched the first of 14 all-women medical units to Serbia, to assist the war effort. Her Scottish Women’s Hospitals went on to recruit more than 1,500 women – and 20 men – to treat thousands in France, Serbia, Corsica, Salonika, Romania, Russia and Malta. -

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women's Suffrage Timeline

National Records of Scotland (NRS) Women’s Suffrage Timeline 1832 – First petition to parliament for women’s suffrage. FAILS Great Reform Act gives vote to more men, but no women 1866 - First mass women’s suffrage petition presented to parliament by J. S. Mill MP 1867 - First women’s suffrage societies set up. Organised campaigning begins 1870 – Women’s Suffrage Bill rejected by parliament Married Women’s Property Act gives married women the right to their own property and money 1872 – Women in Scotland given the right to vote and stand for school boards 1884 – Suffrage societies campaign for the vote through the Third Reform Act. FAILS 1894 – Local Government Act allows women to vote and stand for election at a local level 1897 – National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) formed 1903 – Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) founded by Emmeline Pankhurst 1905 – First militant action. Suffragettes interrupt a political meeting and are arrested 1906 – Liberal Party wins general election 1907 – NUWSS organises the successful ‘United Procession of Women’, the ‘Mud March’ Women’s Enfranchisement Bill reaches a second reading. FAILS Qualification of Women Act: Allows election to borough and county councils Women’s Freedom League formed 1908 – Anti-suffragist Liberal MP, Herbert Henry Asquith, becomes prime minister Women’s Sunday demonstration organised by WSPU in London. Attended by 250, 000 people from around Britain Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WASL) founded by Mrs Humphrey Ward 1909 - Marion Wallace-Dunlop becomes the first suffragette to hunger-strike 20 October – Adela Pankhurst, & four others interrupt a political meeting in Dundee. -

'The Neo-Avant-Garde in Modern Scottish Art, And

‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ CRAIG RICHARDSON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BY PUBLISHED WORK) THE SCHOOL OF FINE ART, THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART 2017 1 ‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ Abstract. The submitted publications are concerned with the historicisation of late-modern Scottish visual art. The underpinning research draws upon archives and site visits, the development of Scottish art chronologies in extant publications and exhibitions, and builds on research which bridges academic and professional fields, including Oliver 1979, Hartley 1989, Patrizio 1999, and Lowndes 2003. However, the methodology recognises the limits of available knowledge of this period in this national field. Some of the submitted publications are centred on major works and exhibitions excised from earlier work in Gage 1977, and Macmillan 1994. This new research is discussed in a new iteration, Scottish art since 1960, and in eight other publications. The primary objective is the critical recovery of little-known artworks which were formed in Scotland or by Scottish artists and which formed a significant period in Scottish art’s development, with legacies and implications for contemporary Scottish art and artists. This further serves as an analysis of critical practices and discourses in late-modern Scottish art and culture. The central contention is that a Scottish neo-avant-garde, particularly from the 1970s, is missing from the literature of post-war Scottish art. This was due to a lack of advocacy, which continues, and a dispersal of knowledge. Therefore, while the publications share with extant publications a consideration of important themes such as landscape, it reprioritises these through a problematisation of the art object. -

Edicai Uvuali

THE I + edicaI+. UVUaLI THE JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION. EDITED BY NORMAN GERALD HORNER, M.A., M.D. VOLUTME I, 1931. JANUARY TO JUNE. XtmEan 0n PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, TAVISTOCK SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.1. i -i r TEx BsxTzSu N.-JUNE, 19311 I MEDICAL JOUUNAI. rI KEY TO DATES AND PAGES. THE following table, giving a key to the dates of issue andI the page numbers of the BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL and SUPPLEMENT in the first volume for 1931, may prove convenient to readers in search of a reference. Serial Date of Journal Supplement No. Issue. Pages. Pages. 3652 Jan. 3rd 1- 42 1- 8 3653 10th 43- 80 9- 12 3654 it,, 17th 81- 124 13- 16 3655 24th 125- 164 17- 24 3656 31st 165- 206 25- 32 3657 Feb. 7th 207- 252 33- 44 3658 ,, 14th 253- 294 45- 52 3659 21st 295- 336 53- 60 3660 28th 337- 382 61- 68 3661 March 7th 383- 432 69- 76 3662 ,, 14th 433- 480 77- 84 3663 21st 481- 524 85- 96 3664 28th 525- 568 97 - 104 3665 April 4th 569- 610 .105- 108 3666 11th 611- 652 .109 - 116 3667 18th 653- G92 .117 - 128 3668 25th 693- 734 .129- 160 3669 May 2nd 735- 780 .161- 188 3670 9th 781- 832 3671 ,, 16th 833- 878 .189- 196 3672 ,, 23rd 879- 920 .197 - 208 3673 30th 921- 962 .209 - 216 3674 June 6th 963- 1008 .217 - 232 3675 , 13th 1009- 1056 .233- 244 3676 ,, 20th 1057 - 1100 .245 - 260 3677 ,, 27th 1101 - 1146 .261 - 276 INDEX TO VOLUME I FOR 1931 READERS in search of a particular subject will find it useful to bear in mind that the references are in several cases distributed under two or more separate -

28415 NDR Credits

28415 NDR Credits Billing Primary Liable party name Full Property Address Primary Liable Party Contact Add Outstanding Debt Period British Airways Plc - (5), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, EH12 9DN Cbre Ltd, Henrietta House, Henrietta Place, London, W1G 0NB 2019 -5,292.00 Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2017 -18,696.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2018 -19,228.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2019 -19,608.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX The Maitland Social Club Per The 70a, Main Street, Kirkliston, EH29 9AB 70 Main Street, Kirkliston, West Lothian, EH29 9AB 2003 -9.00 Secretary/Treasurer 30, Old Liston Road, Newbridge, Midlothian, EH28 The Royal Bank Of Scotland Plc C/O Gva , Po Box 6079, Wolverhampton, WV1 9RA 2019 -519.00 8SS 194a, Lanark Road West, Currie, Midlothian, Martin Bone Associates Ltd (194a) Lanark Road West, Currie, Midlothian, EH14 5NX 2003 -25.20 EH14 5NX C/O Cbre - Corporate Outsourcing, 55 Temple Row, Birmingham, Lloyds Banking Group 564, Queensferry Road, Edinburgh, EH4 6AT 2019 -2,721.60 B2 5LS Unit 3, 38c, West Shore Road, Edinburgh, EH5 House Of Fraser (Stores) Ltd Granite House, 31 Stockwell Street, Glasgow, G1 4RZ 2008 -354.00 1QD Tsb Bank Plc 210, Boswall Parkway, Edinburgh, EH5 2LX C/O Cbre, 55 Temple -

OUR WONDERFUL WORLD Our World, Your Adventure

belmond_directory_2020_138x208mm_160pp_text_pages_AW_6_MAR_2020.qxp_Layout106/03/202014:53Page1 OUR WONDERFUL WORLD Our World, Your Adventure belmond.com belmond_directory_2020_138x208mm_160pp_text_pages_AW_6_MAR_2020.qxp_Layout106/03/202014:53Page2 OUR WONDERFUL WORLD Contents chapter one THE BEGINNING 04/11 chapter two NORTH AMERICA 12/33 chapter three SOUTH AMERICA 34/65 chapter four EUROPE 66/119 chapter five AFRICA 120/131 chapter six ASIA 132/151 chapter seven THE DETAILS 152/159 chapter eight RESERVATIONS 160 belmond_directory_2020_138x208mm_160pp_text_pages_AW_6_MAR_2020.qxp_Layout106/03/202014:53Page4 The Beginning IT POSES AN INTERESTING QUESTION, the beginning. The enigmatic capital letter on a sentence yet unwritten. Perhaps ours began in 1976, when a charismatic entrepreneur purchased the CIPRIANI, Venice’s most glamorous hideaway. Perhaps it began when he decided to reinvent the world’s most romantic train that same year, so the hotel’s illustrious guests could arrive in style. Perhaps it began even earlier. Maybe when Michelangelo decorated the façade of a monastery in the Tuscan hills of Fiesole, or with a clandestine meeting between Rasputin and St Petersburg’s high society. Perhaps it began with HIRAM BINGHAM finding a route back to the lost city of the Incas. Perhaps in the beginning there was nothing, and a nameless voice said “let there be light.” Then they brought the canapés. Our beginning is wrapped in legend and secret; pioneering firsts and time- tested traditions. Perfumed secrets in ancient palaces and jewel-coloured fireworks on a golden beach. Champagne was definitely involved. Each of these fabled yesterdays weave into the adventure of today. Follow BELMOND to 46 unforgettable travel experiences peppered across the world’s most celebrated destinations. -

Information Correct at Time of Issue See

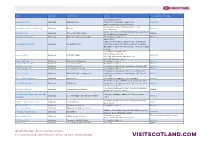

NAME LOCATION DESCRIPTION NOTES PLAN YOUR VISIT / BOOK Pre-booking required Craigmillar Castle Edinburgh Medieval castle Till 31st Oct: open daily, 10am to 4pm Book here Winter opening times to be confirmed. Pre-booking required. Some glasshouses closed. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Edinburgh Gardens Book here Free admission Castle closed. Free entry to the grounds (open daily 08.00- Lauriston Castle Edinburgh 16th-century tower house Walk-in 19.00) and Mimi's Cafe on site. Royal Yacht Britannia Edinburgh Attraction - former royal yacht Pre-booking recommended. Book here Shop is open Tours have been put on hold for the time being due to Edinburgh Gin Distillery Edinburgh Gin distillery tours restrictions in force from 9th Oct, and can't be booked - until further notice. Wee Wonders Online Tasting available instead. Pre-booking recommended. Currently open Thu-Mon Georgian House Edinburgh New Town House Book here 1st - 29th Nov: open Sat-Sun, 10am-4pm 30th Nov- 28th Feb: closed Edinburgh Castle Edinburgh Main castle in Edinburgh Pre-booking required. Book here Real Mary King's Close Edinburgh Underground tour Pre-booking required. Book here Our Dynamic Earth Edinburgh Earth Science Centre Pre-booking required. Open weekends in October only. Book here Edinburgh Dungeon Edinburgh Underground attraction Pre-booking required. Book here Pre-booking recommended. The camera show is not Camera Obscura Edinburgh World of Illusions - rooftop view running at the moment - admission price 10% lower to Book here reflect this. Palace of Holyroodhouse Edinburgh Royal Palace Pre-booking recommended. Open Thu-Mon. Book here Pre-booking required. Whisky is not consumed within Scotch Whisky Experience Edinburgh Whisky tours the premises for now, instead it's given at the end of Book here the tours to take away. -

Women Physicians Serving in Serbia, 1915-1917: the Story of Dorothea Maude

MUMJ History of Medicine 53 HISTORY OF MEDICINE Women Physicians Serving in Serbia, 1915-1917: The Story of Dorothea Maude Marianne P. Fedunkiw, BSc, MA, PhD oon after the start of the First World War, hundreds of One country which benefited greatly from their persistence British women volunteered their expertise , as physi - was Serbia. 2 Many medical women joined established cians, nurses, and in some cases simply as civilians groups such as the Serbian Relief Fund 3 units or the Scottish who wanted to help, to the British War Office . The War Women’s Hospital units set up by Scottish physician Dr. SOffice declined their offer, saying it was too dangerous. The Elsie Inglis. 4 Other, smaller, organized units included those women were told they could be of use taking over the duties which came to be known by the names of their chief physi - of men who had gone to the front, but their skills, intelli - cian or their administrators, including Mrs. Stobart’s Unit, gence and energy were not required at the front lines. Lady Paget’s Unit or The Berry Mission . Many of these This did not deter these women. They went on their own. women wrote their own accounts of their service .5 Still other women went over independently. Dr. Dorothea Clara Maude (1879-1959) was just such a woman. Born near Oxford, educated at University of Oxford and Trinity College, Dublin and trained at London’s Royal Free Hospital, she left her Oxford practice in July 1915 to join her first field unit in northern Serbia. -

Scotland's New Year Festival

SCOTLAND’S NEW YEAR FESTIVAL FOREWORD A very warm welcome to you in our third year of producing Edinburgh’s Hogmanay, as we invite you to BE TOGETHER this Hogmanay. Now more than ever is the time to celebrate ‘togetherness’ and what better way than surrounded by people from all over the world at New Year? From performers to audiences, this festival is about coming together, being together, sharing experiences together and sharing the start of a new year arm in arm and side by side. BE ready to party from the 30th December as we return with a programme of events at the magnificent McEwan Hall. From the return of hit clubbing experience Symphonic Ibiza on 30th December featuring Ibiza DJs and a live orchestra, to the first party in 2020 celebrating the new year along with the Southern Hemisphere at G’Day 2020 with Kylie Auldist on 31 December. Jazz legends Ronnie Scott’s Big Band will play a gala concert on 31st December to give an alternative lead up to the bells and renowned DJ Judge Jules will spin into the wee small hours at our first ever Official After-Party. BE a trailblazer at the Torchlight Procession in partnership with VisitScotland. The historic event culminates in Holyrood Park as torchbearers create a symbol to share with the world: this year two figures holding hands - both residents and visitors to Scotland opening their door to the world and saying BE together. BE in the thick of it at the world famous Street Party hosted by Johnnie Walker, with a brilliantly eclectic programme of music, street theatre and spectacle. -

Mapping Urban Residents' Place Attachment to Historic Environments

Wang, Yang (2021) Mapping urban residents’ place attachment to historic environments: a case study of Edinburgh. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/82345/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Mapping Urban Residents’ Place Attachment to Historic Environments: A Case Study of Edinburgh Yang Wang BE, MArch Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow May 2021 Abstract Place attachment refers to the positive emotional bonds between people and places. Disrupting place attachment has a negative impact on people’s psychological well-being and the health of their communities. Place attachment can motivate people’s engagement in civic actions to protect their beloved places from being destroyed, especially when buildings and public spaces are demolished or redeveloped in historic places. However, the UK planning and heritage sectors have made only limited attempts to understand people’s attachment to the historic environment and how it may influence planning, conservation and development that affects historic places.