Section Notes the Cell Division Cycle Presents an Interesting System To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNA Damage Checkpoint Dynamics Drive Cell Cycle Phase Transitions

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/137307; this version posted August 4, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. DNA damage checkpoint dynamics drive cell cycle phase transitions Hui Xiao Chao1,2, Cere E. Poovey1, Ashley A. Privette1, Gavin D. Grant3,4, Hui Yan Chao1, Jeanette G. Cook3,4, and Jeremy E. Purvis1,2,4,† 1Department of Genetics 2Curriculum for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 3Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics 4Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 120 Mason Farm Road Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7264 †Corresponding Author: Jeremy Purvis Genetic Medicine Building 5061, CB#7264 120 Mason Farm Road Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7264 [email protected] ABSTRACT DNA damage checkpoints are cellular mechanisms that protect the integrity of the genome during cell cycle progression. In response to genotoxic stress, these checkpoints halt cell cycle progression until the damage is repaired, allowing cells enough time to recover from damage before resuming normal proliferation. Here, we investigate the temporal dynamics of DNA damage checkpoints in individual proliferating cells by observing cell cycle phase transitions following acute DNA damage. We find that in gap phases (G1 and G2), DNA damage triggers an abrupt halt to cell cycle progression in which the duration of arrest correlates with the severity of damage. However, cells that have already progressed beyond a proposed “commitment point” within a given cell cycle phase readily transition to the next phase, revealing a relaxation of checkpoint stringency during later stages of certain cell cycle phases. -

Cloning of a D-Type Cyclin from Murine Erythroleukemia Cells (CYL2 Cdna/Cell Cycle) HIROAKI KIYOKAWA*, XAVIER BUSQUETS, C

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 89, pp. 2444-2447, March 1992 Cell Biology Cloning of a D-type cyclin from murine erythroleukemia cells (CYL2 cDNA/cell cycle) HIROAKI KIYOKAWA*, XAVIER BUSQUETS, C. THOMAS POWELL, LANG NGo, RICHARD A. RIFKIND, AND PAUL A. MARKS DeWitt Wallace Research Laboratory, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the Sloan-Kettering Division of the Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Cornell University, New York, NY 10021 Contributed by Paul A. Marks, December 13, 1991 ABSTRACT We report the complete coding sequence of a could be important in regulating G1 cell cycle progression, in cDNA, designated CYL2, derived from a murine erythroleu- governing S-phase commitment to differentiation, or in tu- kemia cell library. CYL2 is considered to encode a D-type morigenesis (27, 28). We now report the isolation and nucle- cyclin because (i) there is cross hybridization with CYL1 (a otide sequence of a D-type cyclin, designated CYL2,t from murine homolog of human cyclin D1) and the encoded protein murine erythroleukemia cells (MELCs). The observed fluc- has 64% amino acid sequence identity with CYL1 and (it) tuation in level ofCYL2 mRNA during the cell cycle suggests murine erythroleukemia cell-derived CYL2 contains an amino a role in commitment to the G1 to S phase transition. acid sequence identical to that previously reported for the C-terminal portion ofa partially sequenced CYL2. Transcripts MATERIALS AND METHODS of murine erythroleukemia cell CYL2 undergo alternative polyadenylylation like that of human cyclin Di. A major Cell Cultures. DS19/Sc9 MELCs, derived from 745A cells 6.5-kilobase CYL2 transcript changes its expression during the (29), were maintained in a-modified minimal essential me- cell cycle with a broad peak through G, and S phases and a dium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum. -

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) and Myosin Light Chain Kinase in Mammalian Eggs

BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION (2015) 92(6):146, 1–14 Published online before print 22 April 2015. DOI 10.1095/biolreprod.114.127027 MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) and Myosin Light Chain Kinase in Mammalian Eggs Affect Myosin-II Function and Regulate the Metaphase II State in a Calcium- and Zinc-Dependent Manner1 Lauren A. McGinnis,3 Hyo J. Lee,3 Douglas N. Robinson,4 and Janice P. Evans2,3 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 4Department of Cell Biology, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland ABSTRACT activation. Inability to exit from metaphase II arrest upon fertilization is associated with female infertility [2, 3]. Proper Vertebrate eggs are arrested at metaphase of meiosis II, a state maintenance of metaphase II arrest in unfertilized eggs is also classically known as cytostatic factor arrest. Maintenance of this crucial for reproductive success, with failure of eggs to arrest until the time of fertilization and then fertilization- maintain metaphase II arrest being associated with reduced induced exit from metaphase II are crucial for reproductive female fertility [4–7]. Reduced ability to maintain metaphase II success. Another key aspect of this meiotic arrest and exit is arrest is also observed in eggs with down-regulated activity of regulation of the metaphase II spindle, which must be appropriately localized adjacent to the egg cortex during endogenous meiotic inhibitor 2 (EMI2), CDC25A, or PP2A, Downloaded from www.biolreprod.org. metaphase II and then progress into successful asymmetric with reduced levels of cytosolic zinc, or undergoing postovu- cytokinesis to produce the second polar body. -

University of Napoli Federico Ii

UNIVERSITY OF NAPOLI FEDERICO II Doctorate School in Molecular Medicine Doctorate Program in Genetics and Molecular Medicine Coordinator: Prof. Lucio Nitsch XXVII Cycle “REGULATION OF p14ARF TUMOR SUPPRESSOR ACTIVITIES AND FUNCTIONS” MICHELA RANIERI Napoli 2015 REGULATION OF p14ARF TUMOR SUPPRESSOR ACTIVITIES AND FUNCTIONS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND 6 1.1 THE HUMAN INK4/ARF LOCUS ENCODES p14ARF PROTEIN. 8 1.2 THE ONCOSUPPRESSIVE ROLE OF p14ARF PROTEIN. 11 1.3 ARF AS AN ONCOGENE: A NEW ROLE. 17 1.4 OTHER FUNCTIONS OF ARF PROTEIN. 20 1.5 ARF TURNOVER. 23 2. PRELIMINARY DATA AND AIM OF THE STUDY. 27 3. MATERIALS AND METHODS. 28 4. RESULTS. 32 4.1 Mutation of Threonine 8 does not affect ARF folding. 32 4.2 Mutation of Threonine 8 affects ARF protein turn-over. 35 4.3 Mimicking ARF phosphorylation inhibits ARF biological activity. 37 4.4 Mimicking Threonine 8 phosphorylation induces ARF accumulation in the cytoplasm and nucleus. 39 4.5 Cytoplasmic localized ARF protein is phosphorylated. 41 4.6 ARF loss blocks cell proliferation in both Hela and HaCat cells. 43 4.7 ARF loss determines a round phenotype of the cells. 46 4.8 Round phenotype is not apoptosis-dependent. 49 4.9 ARF loss induces DAP Kinase-dependent apoptosis. 51 5. DISCUSSION. 54 6. CONCLUSIONS. 63 7. REFERENCES. 64 3 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS RELATED TO THE THESIS. Vivo M, Ranieri M, Sansone F, Santoriello C, Calogero RA, Calabrò V, Pollice A, La Mantia G. “Mimicking p14ARF phosphorylation influences its ability to restrain cell proliferation”. PLoSONE8(1):e53631. -

Interaction of Cdc2 and Rum1 Regulates Start and S-Phase in Fission Yeast

Journal of Cell Science 108, 3285-3294 (1995) 3285 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1995 JCS8905 Interaction of cdc2 and rum1 regulates Start and S-phase in fission yeast Karim Labib1,2,3, Sergio Moreno3 and Paul Nurse1,2,* 1ICRF Cell Cycle Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 1QU, UK 2ICRF, PO Box 123, Lincolns Inn Fields, London WC2A 3PX, UK 3Instituto de Microbiologia-Bioquimica, CSIC/Universidad de Salamanca, Edificio Departamental, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain *Author for correspondence SUMMARY The p34cdc2 kinase is essential for progression past Start in rum1, can disrupt the dependency of S-phase upon mitosis, the G1 phase of the fission yeast cell cycle, and also acts in resulting in an extra round of S-phase in the absence of G2 to promote mitotic entry. Whilst very little is known mitosis. We show that cdc2 and rum1 interact in this about the G1 function of cdc2, the rum1 gene has recently process, and describe dominant cdc2 mutants causing been shown to encode an important regulator of Start in multiple rounds of S-phase in the absence of mitosis. We fission yeast, and a model for rum1 function suggests that suggest that interaction of rum1 and cdc2 regulates Start, it inhibits p34cdc2 activity. Here we present genetic data and this interaction is important for the regulation of S- cdc2 suggesting that rum1 maintains p34 in a pre-Start G1 phase within the cell cycle. form, inhibiting its activity until the cell achieves the critical mass required for Start, and find that in the absence of rum1 p34cdc2 has increased Start activity in vivo. -

Targeting the WEE1 Kinase As a Molecular Targeted Therapy for Gastric Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 31 Research Paper Targeting the WEE1 kinase as a molecular targeted therapy for gastric cancer Hye-Young Kim1,2, Yunhee Cho1,3, HyeokGu Kang1,3, Ye-Seal Yim1,3, Seok-Jun Kim1,3, Jaewhan Song2, Kyung-Hee Chun1,3 1Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea 2Department of Biochemistry, College of Life Science and Biotechnology, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea 3Brain Korea 21 PlusProject for Medical Science, Yonsei University, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea Correspondence to: Kyung-Hee Chun, email: [email protected] Keywords: WEE1, AZD1775 (MK-1775), 5-FU, Paclitaxel, gastric cancer Received: September 07, 2015 Accepted: May 28, 2016 Published: June 23, 2016 ABSTRACT Wee1 is a member of the Serine/Threonine protein kinase family and is a key regulator of cell cycle progression. It has been known that WEE1 is highly expressed and has oncogenic functions in various cancers, but it is not yet studied in gastric cancers. In this study, we investigated the oncogenic role and therapeutic potency of targeting WEE1 in gastric cancer. At first, higher expression levels of WEE1 with lower survival probability were determined in stage 4 gastric cancer patients or male patients with accompanied lymph node metastasis. To determine the function of WEE1 in gastric cancer cells, we determined that WEE1 ablation decreased the proliferation, migration, and invasion, while overexpression of WEE1 increased these effects in gastric cancer cells. We also validated the clinical application of WEE1 targeting by a small molecule, AZD1775 (MK-1775), which is a WEE1 specific inhibitor undergoing clinical trials. -

The Cell Cycle & Mitosis

The Cell Cycle & Mitosis Cell Growth The Cell Cycle is G1 phase ___________________________________ _______________________________ During the Cell Cycle, a cell ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Anaphase Cell Division ___________________________________ Mitosis M phase M ___________________________________ S phase replication DNA Interphase Interphase is ___________________________ ___________________________________ G2 phase Interphase is divided into three phases: ___, ___, & ___ G1 Phase S Phase G2 Phase The G1 phase is a period of The S phase replicates During the G2 phase, many of activity in which cells _______ ________________and the organelles and molecules ____________________ synthesizes _______ molecules. required for ____________ __________ Cells will When DNA replication is ___________________ _______________ and completed, _____________ When G2 is completed, the cell is synthesize new ___________ ____________________ ready to enter the ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Mitosis are divided into four phases: _____________, ______________, _____________, & _____________ Below are cells in two different phases of the cell cycle, fill in the blanks using the word bank: Chromatin Nuclear Envelope Chromosome Sister Chromatids Nucleolus Spinder Fiber Centrosome Centrioles 5.._________ 1.__________ v 6..__________ 2.__________ 7.__________ 3.__________ 8..__________ 4.__________ v The Cell Cycle & Mitosis Microscope Lab: -

Label the Parts of the Cell Cycle Diagram and Briefly Describe What Is Happening: a B C D E F G H I J 1) Chromosomes Move To

Label the parts of the cell cycle diagram and briefly describe what is happening: A Interphase - cell is growing and preparing for division. B G1 - growth and normal cell function C S - DNA replication D G2 - growth, preparation for division, duplicate organelles E Prophase - nuclear envelope dissolves, mitotic apparatus set up, DNA condenses. F Metaphase - chromosome line up in center G Anaphase - sister chromatids separate and are pulled to poles of cell. H Telophase - nuclei reform, DNA relaxes into chromatin, cleaveage furrow or cell plate forms I Mitosis - nuclear division J Cytokinesis - the rest of the cell divides 1) Chromosomes move to the middle of the cell during what phase? 2) What are sister chromatids? 3) What holds the chromatids together? 4) When do the sister chromatids separate? 5) During which phase do chromosomes first become visible? 6) During which phase does the cleavage furrow start forming? 7) What is another name for mitosis? 8) What is the structure that breaks the spindle fiber into 2? 9) What makes up the mitotic apparatus? 10) Complete the table by checking the correct column for each statement. Statement Interphase Mitosis Cell growth occurs Nuclear division occurs Chromosomes are finishing moving into separate daughter cells. Normal functions occur Chromosomes are duplicated DNA synthesis occurs Cytoplasm divides immediately after this period Mitochondria and other organelles are made. The Animal Cell Cycle – Phases are out of order 11) Which cell is in metaphase? 12) Cells A and F show an early and late stage of the same phase of mitosis. What phase is it? 13) In cell A, what is the structure labeled X? 14) In cell F, what is the structure labeled Y? 15) Which cell is not in a phase of mitosis? 16) A new membrane is forming in B. -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

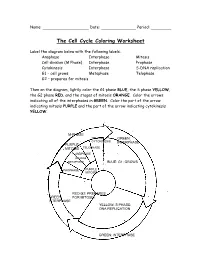

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase. -

Working on Genomic Stability: from the S-Phase to Mitosis

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Working on Genomic Stability: From the S-Phase to Mitosis Sara Ovejero 1,2,3,* , Avelino Bueno 1,4 and María P. Sacristán 1,4,* 1 Instituto de Biología Molecular y Celular del Cáncer (IBMCC), Universidad de Salamanca-CSIC, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 2 Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS, University of Montpellier, 34000 Montpellier, France 3 Department of Biological Hematology, CHU Montpellier, 34295 Montpellier, France 4 Departamento de Microbiología y Genética, Universidad de Salamanca, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.O.); [email protected] (M.P.S.); Tel.: +34-923-294808 (M.P.S.) Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 20 February 2020 Abstract: Fidelity in chromosome duplication and segregation is indispensable for maintaining genomic stability and the perpetuation of life. Challenges to genome integrity jeopardize cell survival and are at the root of different types of pathologies, such as cancer. The following three main sources of genomic instability exist: DNA damage, replicative stress, and chromosome segregation defects. In response to these challenges, eukaryotic cells have evolved control mechanisms, also known as checkpoint systems, which sense under-replicated or damaged DNA and activate specialized DNA repair machineries. Cells make use of these checkpoints throughout interphase to shield genome integrity before mitosis. Later on, when the cells enter into mitosis, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) is activated and remains active until the chromosomes are properly attached to the spindle apparatus to ensure an equal segregation among daughter cells.