Task Force Ranger in Somalia 1St Special Forces Operational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ranger Handbook) Is Mainly Written for U.S

SH 21-76 UNITED STATES ARMY HANDBOOK Not for the weak or fainthearted “Let the enemy come till he's almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him with your hatchet.” Major Robert Rogers, 1759 RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE United States Army Infantry School Fort Benning, Georgia FEBRUARY 2011 RANGER CREED Recognizing that I volunteered as a Ranger, fully knowing the hazards of my chosen profession, I will always endeavor to uphold the prestige, honor, and high esprit de corps of the Rangers. Acknowledging the fact that a Ranger is a more elite Soldier who arrives at the cutting edge of battle by land, sea, or air, I accept the fact that as a Ranger my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other Soldier. Never shall I fail my comrades I will always keep myself mentally alert, physically strong, and morally straight and I will shoulder more than my share of the task whatever it may be, one hundred percent and then some. Gallantly will I show the world that I am a specially selected and well trained Soldier. My courtesy to superior officers, neatness of dress, and care of equipment shall set the example for others to follow. Energetically will I meet the enemies of my country. I shall defeat them on the field of battle for I am better trained and will fight with all my might. Surrender is not a Ranger word. I will never leave a fallen comrade to fall into the hands of the enemy and under no circumstances will I ever embarrass my country. -

COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR (Retired) RICHARD E

COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR (Retired) RICHARD E. MERRITT Command Sergeant Major (CSM) (R) Rick Merritt retired from active duty in the U.S. Army after serving almost 36 years since he entered the military in March of 1984. He and his family returned from South Korea in December 2018 after he served as the Command Senior Enlisted Leader (CSEL) (for all US Army Forces) advising the Commander, EIGHTH US ARMY for 3 ½ years. His last assignment before retirement was with the US Army Special Operations Command with duty at Hunter Army Airfield, attached to the 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. His first duty assignment in the Army after becoming an Infantryman was with Company C, 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, Illesheim, Germany as a Rifleman and M60 Machine Gunner. CSM (R) Merritt served 25 years in the 75th Ranger Regiment. His initial service started with Company B, 3rd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning, Ga., as a Squad Automatic Rifleman, Fire Team Leader, Rifle Squad Leader, Weapons Squad Leader, and Rifle Platoon Sergeant. A follow-on assignment included one year with the Ranger Indoctrination Program at the 75th Ranger Regimental Ranger Training Detachment. In 1996, he was assigned to the Jungle Operations Training Battalion as a Senior Instructor and Team Sergeant at the U.S. Army Jungle School, Fort Sherman, Panama. He served there for 17 months and then was assigned to 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment at Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, GA as a Rifle Platoon Sergeant with Company B, the Battalion Intelligence and Operations Sergeant in Headquarters Company and as the First Sergeant of Company C. -

Analysis of Operation Gothic Serpent: TF Ranger in Somalia (Https:Asociweb.Soc.Mil/Swcs/Dotd/Sw-Mag/Sw-Mag.Htm)

Special Warfare The Professional Bulletin of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School PB 80–03–4 May 2004 Vol. 16, No. 4 From the Commandant Special Warfare In recent years, the JFK Special Warfare Center and School has placed a great emphasis on the Special Forces training pipeline, and much of our activity has been concerned with recruiting, assessing and training Special Forces Soldiers to enter the fight against terrorism. Less well-publicized, but never- theless important, are our activi- ties devoted to training Special Forces Soldiers in advanced skills. These skills, such as mili- focus on a core curriculum of tary free-fall, underwater opera- unconventional warfare and tions, target interdiction and counterinsurgency, coupled with urban warfare, make our Soldiers advanced human interaction and more proficient in their close- close-quarters combat, has combat missions and better able proven to be on-the-mark against to infiltrate and exfiltrate with- the current threat. out being detected. Located at Fort Bragg, at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz., and at Key West, Fla., the cadre of the 2nd Battal- ion, 1st Special Warfare Training Group provides such training. Major General Geoffrey C. Lambert Not surprisingly, the global war on terrorism has engendered greater demand for Soldiers with selected advanced skills. Despite funding constraints and short- ages of personnel, SWCS military and civilian personnel have been innovative and agile in respond- ing to the new requirements. The success of Special Forces Soldiers in the global war on ter- rorism has validated our training processes on a daily basis. Our PB 80–03–4 Contents May 2004 Special Warfare Vol. -

Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: a Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999

Document generated on 09/27/2021 3:15 p.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999. Stephen M. Grenier Volume 20, Number 1, Spring 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs20_01br05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, S. M. (2000). Review of [Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 20(1), 193–195. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999. Mark Bowden's Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War is a dramatic, minute-by- minute account of the climatic battle in the unsuccessful campaign to end the human suffering in Somalia. The Battle of the Black Sea, as it is known, was the most intense fighting involving American troops since the Vietnam War, resulting in 18 American soldiers and over 500 Somalis killed. -

One Hundred Sixteenth Congress of the United States of America

S. 743 One Hundred Sixteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Friday, the third day of January, two thousand and twenty An Act To award a Congressional Gold Medal to the soldiers of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), commonly known as ‘‘Merrill’s Marauders’’, in recognition of their bravery and outstanding service in the jungles of Burma during World War II. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Merrill’s Marauders Congres- sional Gold Medal Act’’. SEC. 2. FINDINGS. Congress finds that— (1) in August 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other Allied leaders proposed the creation of a ground unit of the Armed Forces that would engage in a ‘‘long-range penetration mission’’ in Japanese-occupied Burma to— (A) cut off Japanese communications and supply lines; and (B) capture the town of Myitkyina and the Myitkyina airstrip, both of which were held by the Japanese; (2) President Roosevelt issued a call for volunteers for ‘‘a dangerous and hazardous mission’’ and the call was answered by approximately 3,000 soldiers from the United States; (3) the Army unit composed of the soldiers described in paragraph (2)— (A) was officially designated as the ‘‘5307th Composite Unit (Provisional)’’ with the code name ‘‘Galahad’’; and (B) later became known as ‘‘Merrill’s Marauders’’ (referred to in this section as the ‘‘Marauders’’) in reference -

GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993

RAID GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993 CLAYTON K.S. CHUN GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993 CLAYTON K.S. CHUN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 04 ORIGINS 08 Clans go to War 10 The UN versus Aideed 11 INITIAL STRATEGY 14 Task Force Ranger Forms 15 A Study in Contrasts: US/UN forces and the SNA 17 TFR’s Tactics and Procedures 25 TFR Operations Against Aideed and the SNA 27 PLAN 31 TFR and the QRF Prepare for Action 32 Black Hawks and Little Birds 34 Somali Preparations 35 RAID 38 “Irene”: Going into the “Black Sea” 39 “Super 61’s Going Down” 47 Ground Convoy to the Rescue 51 Super 64 Goes Down 53 Securing Super 61 59 Mounting Another Rescue 60 TFR Hunkers Down for the Night 65 Confusion on National Street 68 TFR Gets Out 70 ANALYSIS 72 CONCLUSION 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 78 INDEX 80 INTRODUCTION Me and Somalia against the world Me and my clan against Somalia Me and my family against the clan Me and my brother against my family Me against my brother. Somali Proverb In 1992, the United States basked in the glow of its recent military and political victory in Iraq. Washington had successfully orchestrated a coalition of nations, including Arabic states, to liberate Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. The US administration was also celebrating the fall of the Soviet Union and the bright future of President George H.W. Bush’s “New World Order.” The fear of a nuclear catastrophe seemed remote given the international growth of democracy. With the United States now as the sole global superpower, some in the US government felt that it now had the opportunity, will, and capability to reshape the world by creating democratic states around the globe. -

Black Hawk Down

Black Hawk Down A Story of Modern War by Mark Bowden, 1951- Published: 1999 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication & The Assault Black Hawk Down Overrun The Alamo N.S.D.Q. Epilogue Sources Acknowledgements J J J J J I I I I I For my mother, Rita Lois Bowden, and in memory of my father, Richard H. Bowden It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting the ultimate practitioner. Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian The Assault 1 At liftoff, Matt Eversmann said a Hail Mary. He was curled into a seat between two helicopter crew chiefs, the knees of his long legs up to his shoulders. Before him, jammed on both sides of the Black Hawk helicopter, was his „chalk,“ twelve young men in flak vests over tan desert camouflage fatigues. He knew their faces so well they were like brothers. The older guys on this crew, like Eversmann, a staff sergeant with five years in at age twenty-six, had lived and trained together for years. Some had come up together through basic training, jump school, and Ranger school. They had traveled the world, to Korea, Thailand, Central America … they knew each other better than most brothers did. They‘d been drunk together, gotten into fights, slept on forest floors, jumped out of airplanes, climbed mountains, shot down foaming rivers with their hearts in their throats, baked and frozen and starved together, passed countless bored hours, teased one another endlessly about girlfriends or lack of same, driven out in the middle of the night from Fort Benning to retrieve each other from some diner or strip club out on Victory Drive after getting drunk and falling asleep or pissing off some barkeep. -

8.16 Mogadishu PREVIEW

Nonfiction Article of the Week Table of Contents 8-16: The Battle of Mogadishu Terms of Use 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Activities, Difficulty Levels, Common Core Alignment, & TEKS 4 Digital Components/Google Classroom Guide 5 Teaching Guide, Rationale, Lesson Plans, Links, and Procedures: EVERYTHING 6-9 Article: The Battle of Mogadishu 10-11 *Modified Article: The Battle of Mogadishu 12-13 Activity 1: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Multiple Choice w/Key 14-15 Activity 2: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Open-Ended Questions w/Key 16-17 Activity 3: Text Evidence Activity w/Annotation Guide for Article 18-20 Activity 4: Text Evidence Activity & Answer Bank w/Key 21-23 Activity 5: Skill Focus – RI.8.7 Evaluate Mediums (Adv. and Disadv. of Each) 24-27 Activity 6: Integrate Sources –Video Clips & Questions w/Key 28-29 Activity 7: Skills Test Regular w/Key 30-33 Activity 8: Skills Test *Modified w/Key 34-37 ©2019 erin cobb imlovinlit.com Nonfiction Article of the Week Teacher’s Guide 8-16: The Battle of Mogadishu Activities, Difficulty Levels, and Common Core Alignment List of Activities & Standards Difficulty Level: *Easy **Moderate ***Challenge Activity 1: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Multiple Choice* RI.8.1 Activity 2: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Open-Ended Questions* RI.8.1 Activity 3: Text Evidence Activity w/Annotation Guide for Article** RI.8.1 Activity 4: Text Evidence Activity w/Answer Bank** RI.8.1 Activity 5: Skill Focus – Evaluate Mediums*** RI.8.7 Activity 6: Integrate Sources – Video Clip*** RI.8.7, RL.8.7 Activity -

Cpl Benjamin C. Dillon, 22, Was a Gun Team Leader Assigned to 3Rd Battalion, 75Th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning, Ga

Cpl Benjamin C. Dillon, 22, was a gun team leader assigned to 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning, Ga. He was killed on Oct. 6, 2007, in Mosul, Iraq, while engaged in combat operations against known enemies of the United States of America in Northern Iraq. He was a veteran of operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. In the early dawn, Ben layed down gun fire at an unknown enemy driving a small vehicle loaded explosives toward the returning teams, that included many of the most elite military soldiers know: Special Forces Delta team, who honored Ben’s name in their memorial garden, the Army Rangers, Navy Seals, and the Marines who were coming back from a very successful night mission that a few stories have been written about. Ben initially entered the United States Army in his senior year in the delayed entry program in 2003. After graduating from Southeast High School. He then went to basic training on September 24, 2004. He completed One Station Unit Training at Fort Benning as an infantryman, receiving awards for receiving a “Superior Performance” for Physical Fitness Test and being selected as “1st Platoon Honor Graduate” in 2005. Next after graduating from the Basic Airborne Course, he was assigned to the Ranger Indoctrination Program also at Fort Benning. 3 months of training program that never let them sleep more than 15 minutes, eat in 5 minutes and took 20 pounds of weight off that he didn’t have to give. It is said that RIP also takes 10 years off your life span. -

Lead Inspector General for Operation Freedom's Sentinel April 1, 2021

OFS REPORT TO CONGRESS FRONT MATTER OPERATION FREEDOM’S SENTINEL LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS APRIL 1, 2021–JUNE 30, 2021 FRONT MATTER ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of Inspectors General for Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operation. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operation. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OFS. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, and evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operation and activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about OFS and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from other sources, including official documents, congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

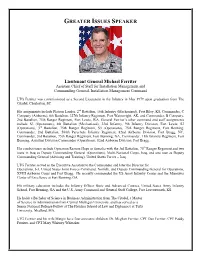

Greater Issues Speaker

GREATER ISSUES SPEAKER Lieutenant General Michael Ferriter Assistant Chief of Staff for Installation Management and Commanding General, Installation Management Command LTG Ferriter was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Infantry in May 1979 upon graduation from The Citadel, Charleston, SC. His assignments include Platoon Leader, 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry (Mechanized), Fort Riley, KS, Commander, C Company (Airborne), 6th Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, Fort Wainwright, AK, and Commander, B Company, 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Lewis, WA. General Ferriter’s other command and staff assignments include S3 (Operations), 4th Battalion (Mechanized), 23rd Infantry, 9th Infantry Division, Fort Lewis, S3 (Operations), 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, S3 (Operations), 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, Commander, 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, NC, Commander, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, GA, Commander, 11th Infantry Regiment, Fort Benning, Assistant Division Commander (Operations), 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg. His combat tours include Operation Restore Hope in Somalia with the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment and two tours in Iraq as Deputy Commanding General (Operations), Multi-National Corps, Iraq, and one tour as Deputy Commanding General (Advising and Training), United States Forces – Iraq. LTG Ferriter served as the Executive Assistant to the Commander and later the Director for Operations, J-3, United States Joint Forces Command, Norfolk, and Deputy Commanding General for Operations, XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg. He recently commanded the US Army Infantry Center and the Maneuver Center of Excellence at Fort Benning, GA. His military education includes the Infantry Officer Basic and Advanced Courses, United States Army Infantry School, Fort Benning, GA and the U.S. -

Patrolling Fall

PATROLLING WINTER 2007 75 TH RANGER REGIMENT ASSOCIATION, INC. VOLUME 22 ISSUE III Color Guard, Dedication of First Ranger Battalion, 75th Infantry Regiment, Hunter Army Airfield, GA, October 18, 2007. Photo by J. Chester Officers’ Messages ..................................1-7 General ....................................8-24 & 67-73 Unit Reports ........................................25-66 CHINA - BURMA - INDIA VIETNAM IRAN GRENADA PANAMA IRAQ SOMALIA AFGHANISTAN PATROLLING – WINTER 2007 WHO WE ARE: The 75th Ranger Regiment Association, Inc., is a regis - We have funded trips for families to visit their wounded sons and husbands tered 501 (c) corporation, registered in the State of Georgia. We were while they were in the hospital. We have purchased a learning program founded in 1986 by a group of veterans of F/58, (LRP) and L/75 (Ranger). soft ware for the son of one young Ranger who had a brain tumor removed. The first meeting was held on June 7, 1986, at Ft. Campbell, KY. The Army took care of the surgery, but no means existed to purchase the OUR MISSION: learning program. We fund the purchase of several awards for graduates 1. To identify and offer membership to all eligible 75th Infantry Rangers, of RIP and Ranger School. We have contributed to each of the three Bat - and members of the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol talion’s Memorial Funds and Ranger Balls, and to the Air - Companies, Long Range Patrol Companies, Ranger borne Memorial at Ft. Benning. Companies and Detachments, Vietnamese Ranger Advi - We have bi-annual reunions and business meetings. Our sors of the Biet Dong Quan; members of LRSU units that Officers, (President, 1st & 2nd Vice-Presidents, Secretary trace their lineage to Long Range Patrol Companies that & Treasurer), are elected at this business meeting.