Bench Brief of the Receiver Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

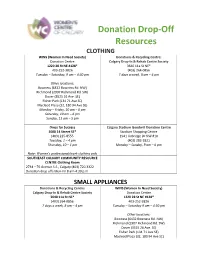

Donation Drop-Off Resources

Donation Drop-Off Resources CLOTHING WINS (Women In Need Society) Donations & Recycling Centre: Donation Centre Calgary Drop-In & Rehab Centre Society 1220 28 St NE #128* 3640 11a St NE* 403-252-3826 (403) 264-0856 Tuesday – Saturday, 9 am – 4:30 pm 7 days a week, 8 am – 4 pm Other locations: Bowness (6432 Bowness Rd. NW) Richmond (2907 Richmond Rd. SW) Dover (3525 26 Ave. SE) Fisher Park (134 71 Ave SE) Macleod Plaza (32, 180 94 Ave SE) Monday – Friday, 10 am – 6 pm Saturday, 10 am – 6 pm Sunday, 11 am – 5 pm Dress for Success Calgary Stadium Goodwill Donation Centre 1008 14 Street SE* Stadium Shopping Centre (403) 225-8555 1941 Uxbridge Dr NW #10 Tuesday, 1 – 4 pm (403) 282-2821 Thursday, 10 – 1 pm Monday – Sunday, 9 am – 6 pm Note: Women’s professional/work clothing only SOUTHEAST CALGARY COMMUNITY RESOURCE CENTRE Clothing Room 2734 – 76 Avenue S.E., Calgary (403) 720-3322 Donation drop offs Mon-Fri 8 am-4:30 p.m SMALL APPLIANCES Donations & Recycling Centre: WINS (Women In Need Society) Calgary Drop-In & Rehab Centre Society Donation Centre 3640 11a St NE* 1220 28 St NE #128* (403) 264-0856 403-252-3826 7 days a week, 8 am – 4 pm Tuesday – Saturday 9 am – 4:30 pm Other locations: Bowness (6432 Bowness Rd. NW) Richmond (2907 Richmond Rd. SW) Dover (3525 26 Ave. SE) Fisher Park (134 71 Ave SE) Macleod Plaza (32, 180 94 Ave SE) Monday - Friday, 10 am – 6 pm; Saturday, 11 am – 6 pm; Sunday 11 am – 5 pm *Locations marked with an asterisk (*) are a 10-minute drive away or less. -

2001-05482 Court Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta

COURT FILE NO.: 2001-05482 COURT COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CENTRE CALGARY PROCEEDINGS IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, RSC 1985, c C-36, as amended AND IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF JMB CRUSHING SYSTEMS INC. and 2161889 ALBERTA LTD. APPLICANTS JMB CRUSHING SYSTEMS INC. and 2161889 ALBERTA LTD. Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP GOWLING WLG 1600, 421 – 7th Avenue SW (CANADA) LLP Calgary, AB T2P 4K9 MATTER NO. Attn: Tom Cumming/Caireen E. Hanert/Stephen Kroeger Phone: 403-298-1938 / 403-298-1992 /403-298-1018 Fax: 403-263-9193 File No.:A163514 DOCUMENT: SERVICE LIST PARTY RELATIONSHIP Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP Counsel for Applicants, JMB 1600, 421 7th Avenue SW Crushing Systems Inc. and 2161889 Calgary AB T2P 4K9 Alberta Ltd. Attention: Tom Cumming Phone: 403-298-1938 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Caireen E. Hanert Phone: 403-298-1992 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Stephen Kroeger Phone: 403-298-1018 E-mail: [email protected] ACTIVE_CA\ 44753500\1 - 2 - PARTY RELATIONSHIP McCarthy Tetrault LLP Counsel for the Monitor Suite 4000, 421 7th Ave SW Calgary, AB T2P 4K9 Attention: Sean F. Collins Phone: 403-260-3531 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Pantelis Kyriakakis Phone: 403-260-3536 Email: [email protected] FTI Consulting Canada Monitor Suite 1610, 520 – 5th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 3R7 Attention: Deryck Helkaa Phone: 403-454-6031 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Tom Powell Phone: 1-604-551-9881 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Mike Clark Phone: 1-604-484-9537 E-mail: [email protected] Attention: Brandi Swift Phone: 1-403-454-6038 E-mail: [email protected] Miller Thomson LLP Counsel for Fiera Private Debt Fund Suite 5800, 40 King Street West VI LP, by its General Partner Toronto, ON M5H 3S1 Integrated Private Debt Fund GP Inc. -

Regular Council Meeting

Town of Drumheller COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA Monday, July 20, 2020 at 4:30 PM Council Chamber, Town Hall 224 Centre Street, Drumheller, Alberta Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2.1. Agenda for July 20, 2020 Regular Council Meeting. Motion: That Council adopt the July 20, 2020 Regular Council Meeting agenda as presented. 3. MINUTES 4 - 7 3.1. Minutes for the July 6, 2020 Regular Council Meeting. Motion: That Council adopt the July 6, 2020 Regular Council Meeting minutes as presented. Regular Council - 06 Jul 2020 - Minutes 4. MINUTES OF MEETING PRESENTED FOR INFORMATION 8 - 9 4.1. Valley Bus Society July 2020 Meeting Minutes Motion: That Council accept the minutes of the July 2020 Valley Bus Society Meeting for information. Valley Bus Society July 2020 Meeting Minutes 5. DELEGATIONS 10 - 18 5.1. RCMP - Staff Sergeant Ed Bourque - Report Presentation 2020 Policing Survey Trends 6. ADMINISTRATION REQUEST FOR DECISION AND REPORTS 6.1. CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER 6.1.1. Covid-19 Town of Drumheller Update 19 - 21 6.1.2. Municipal Development Plan Bylaw 14.20 - Rezoning Amendment - Industrial Development to Industrial Development/Compatible Commercial Development Please Note: A Public Hearing will be held Tuesday August 4, 2020. Motion: That Council give first reading to Municipal Development Plan Bylaw No.14.20 to amend Municipal Development Plan Bylaw 11.08 for the Town of Drumheller. Drumheller MDP Amending Bylaw 14.20 22 - 24 6.1.3. Land Use Bylaw 15.20 - Uses and Rules for Direct Control District Please Note: A Public Hearing will be held Tuesday August 4, 2020. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Alberta Hansard Thursday, November 4, 2010 Issue 39 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL) Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (WA), Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) WA Opposition House Leader Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC), Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Official Opposition Deputy Leader, Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (WA) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Morton, Hon. F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Government Whip ND Opposition House Leader Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL), Oberle, Hon. -

To See the Printable PDF

Chestermere Seniors’ Resource Handbook EMERGENCY SERVICES IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, CALL 911 Ambulance • Fire • Police Hearing Impaired Emergencies • Ambulance ........................................................ 403-268-3673 • Fire .................................................................... 403-233-2210 • Police ................................................................ 403-265-7392 Chestermere Emergency Management Agency 403-207-7050 CHEMA coordinates disaster assistance and relief efforts in the event of a city-wide emergency. Chestermere Utilities Emergency Numbers • Gas - ATCO 24/7 ............................................. 1-800-511-3447 If you smell natural gas or have no heat in your home. • Electricity - FortisAlberta 24/7 .......................... 403-310-9473 Check the outage map on the website first. • Water/sewer - EPCOR Trouble line ................ 1-888-775-6677 Poison Centre (Alberta Health Services) 1-800-332-1414 * * * * * * Centre for Suicide Prevention 24/7 help line: 1-833-456-4566 (Calgary) or text 4564 (2-10 p.m.) Distress Centre 24/7 Crisis Line: 403-266-4357 (Calgary) distresscentre.com [email protected] Kerby Elder Abuse (To report or get info) 403-705-3250 (Calgary) Mental Health Help Line 24/7 help line: 1-877-303-2642 (Alberta Health Services) Table of Contents EMERGENCY SERVICES ......................................Pull-out sheet CITY OF CHESTERMERE - HANDY NUMBERS ......................... 1 ADVOCACY & SUPPORT GROUPS ......................................... 3 ARTS, CULTURE & ENTERTAINMENT -

Monitor's Fifth Report

COURT FILE 2001 06423 Clerk's NUMBER Stamp COURT COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH OF ALBERTA JUDICIAL CALGARY CENTRE IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, as amended AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF ENTREC CORPORATION, CAPSTAN HAULING LTD., ENTREC ALBERTA LTD., ENT CAPITAL CORP., ENTREC CRANES & HEAVY HAUL INC., ENTREC HOLDINGS INC., ENT OILFIELD GROUP LTD. and ENTREC SERVICES LTD. DOCUMENT FIFTH REPORT OF THE MONITOR October 5, 2020 ADDRESS FOR MONITOR SERVICE AND Alvarez & Marsal Canada Inc. CONTACT 250 6th Avenue SW, Suite 1110 INFORMATION Calgary, AB T2P 3H7 OF PARTY FILING THIS Phone: +1 604.638.7440 DOCUMENT Fax: +1 604.638.7441 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Attention: Anthony Tillman / Vicki Chan COUNSEL Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP 400 3rd Avenue SW, Suite 3700 Calgary, Alberta T2P 4H2 Phone: +1 403.267.8222 Fax: +1 403.264.5973 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Attention: Howard A. Gorman, Q.C. / Gunnar Benediktsson TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... - 3 - 2.0 PURPOSE ................................................................................................................................... - 6 - 3.0 TERMS OF REFERENCE ......................................................................................................... - 7 - 4.0 ACTIVITIES OF THE -

2020 Annual Report the Year-Over-Year Increase of $75.3 Million in Long-Term Debt the Operating Facility of $33.3 Million (2019 – $12.3 Million)

CMLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020 2 3 CONTENTS 04 INTRODUCTION 42 STRATEGIC PLAN UPDATE 08 HIGHLIGHTS & MILESTONES 47 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S OF 2020 REPORT 10 City-building highlights 50 ACCOUNTABILITY & 15 Planning & infrastructure GOVERNANCE 19 Land sales & 57 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION commercial leasing & ANALYSIS 22 Development partner activity 61 REPORT OF MANAGEMENT 26 Retail openings 62 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 30 Project management 68 NOTES TO FINANCIAL 34 Programming & public art STATEMENTS 38 Marketing 84 TEAM CMLC 40 Corporate communications 41 Safety & vitality 4 5 “In a truly extraordinary year, CMLC rose above countless challenges and delivered, INTRODUCTION as always, exceptional projects for our city and outstanding value for our shareholder. Despite the limitations everyone faced in a year defined by COVID-19, where our daily routines and typical ways of working were completely upended, CMLC found ways to roll with the punches and forge stalwartly onward with our important community- building work.” KATE THOMPSON President & CEO 7 RISING TO NEW CHALLENGES For nearly everyone on the planet, 2020 was a year dramatically defined by the challenges and the changes wrought by the COVID-19 crisis. As its ripple effects reverberated through our community, our resilience as an organization was put swiftly and continually to the test. And, as we’ve always done in the face of unforeseen obstacles, after calmly and thoughtfully taking stock of our projects and the risks we now had to consider, CMLC rose confidently to these new challenges. This new world order called for extraordinary adaptations in every facet of our business—our ongoing redevelopment and construction activities, the many ways we support our partners, and the placemaking and community programming initiatives that have underpinned our success here in Calgary’s east end from the outset. -

Meet Calgary Air Travel

MEET CALGARY AIR TRAVEL London (Heathrow) Amsterdam London (Gatwick) Frankfurt Seattle Portland Minneapolis Salt Lake City New York (JFK) Chicago Newark Denver San Francisco Las Vegas Palm Springs Los Angeles Dallas/Ft.Worth San Diego Phoenix Houston Orlando London (Heathrow) Amsterdam San Jose del Cabo Varadero Puerto Vallarta Cancun London (Gatwick) Mexico City Frankfurt Montego Bay Seattle Portland Minneapolis Salt Lake City New York (JFK) Chicago Newark Denver San Francisco Las Vegas Palm Springs Los Angeles Dallas/Ft.Worth San Diego Phoenix Houston Orlando San Jose del Cabo Varadero Puerto Vallarta Cancun Mexico City Montego Bay Time Zone Passport Requirements Calgary, Alberta is on MST Visitors to Canada require a valid passport. (Mountain Standard Time) For information on visa requirements visit Canada Border Services Agency: cbsa-asfc.gc.ca CALGARY AT A GLANCE HOTEL & VENUES Calgary is home to world-class accommodations, with over 13,000 guest rooms, there’s Alberta is the only province in +15 Calgary’s +15 Skywalk system Canada without a provincial sales Skywalk is the world’s largest indoor, something for every budget and preference. Meetings + Conventions Calgary partners with tax (PST). The Government of pedestrian pathway network. The Calgary’s hotels and venues to provide event planners with direct access to suppliers without the added step of connecting with each facility individually. Canada charges five per cent goods weather-protected walkways are and services tax (GST) on most about 15 feet above the ground purchases. level and run for a total of 11 miles. Calgary TELUS The +15 links Calgary’s downtown Convention Centre Bring your shades. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 30th Legislature First Session Alberta Hansard Wednesday afternoon, May 22, 2019 Day 1 The Honourable Nathan Cooper, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 30th Legislature First Session Cooper, Hon. Nathan, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (UCP), Speaker Pitt, Angela D., Airdrie-East (UCP), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Milliken, Nicholas, Calgary-Currie (UCP), Deputy Chair of Committees Aheer, Hon. Leela Sharon, Chestermere-Strathmore (UCP) Nally, Hon. Dale, Morinville-St. Albert (UCP) Allard, Tracy L., Grande Prairie (UCP) Neudorf, Nathan T., Lethbridge-East (UCP) Amery, Mickey K., Calgary-Cross (UCP) Nicolaides, Hon. Demetrios, Calgary-Bow (UCP) Armstrong-Homeniuk, Jackie, Nielsen, Christian E., Edmonton-Decore (NDP) Fort Saskatchewan-Vegreville (UCP) Nixon, Hon. Jason, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (UCP) (UCP), Government House Leader Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (NDP), Nixon, Jeremy P., Calgary-Klein (UCP) Official Opposition House Leader Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (NDP), Carson, Jonathon, Edmonton-West Henday (NDP) Leader of the Official Opposition Ceci, Joe, Calgary-Buffalo (NDP) Orr, Ronald, Lacombe-Ponoka (UCP) Copping, Hon. Jason C., Calgary-Varsity (UCP) Pancholi, Rakhi, Edmonton-Whitemud (NDP) Dach, Lorne, Edmonton-McClung (NDP) Panda, Hon. Prasad, Calgary-Edgemont (UCP) Dang, Thomas, Edmonton-South (NDP) Phillips, Shannon, Lethbridge-West (NDP) Deol, Jasvir, Edmonton-Meadows (NDP) Pon, Hon. Josephine, Calgary-Beddington (UCP) Dreeshen, Hon. Devin, Innisfail-Sylvan Lake (UCP) Rehn, Pat, Lesser Slave Lake (UCP) Eggen, David, Edmonton-North West (NDP), Reid, Roger W., Livingstone-Macleod (UCP) Official Opposition Whip Renaud, Marie F., St. Albert (NDP) Ellis, Mike, Calgary-West (UCP), Government Whip Rosin, Miranda D., Banff-Kananaskis (UCP) Feehan, Richard, Edmonton-Rutherford (NDP) Rowswell, Garth, Vermilion-Lloydminster-Wainwright (UCP) Fir, Hon. -

Electoral Divisions Act

Province of Alberta ELECTORAL DIVISIONS ACT Statutes of Alberta, 2017 Chapter E-4.3 Current as of March 19, 2019 © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer Suite 700, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this document are reminded that it has no legislative sanction. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. ELECTORAL DIVISIONS ACT Chapter E-4.3 Table of Contents 1 Electoral divisions 2 Names of electoral divisions 3 Description of electoral divisions 4 Regulations 5 Transitional 6 Repeal 7 Coming into force Schedule HER MAJESTY, by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta, enacts as follows: Electoral divisions 1 The electoral divisions for the purposes of the Election Act are the 87 electoral divisions established by this Act. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday, March 15, 2011 Issue 13 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (WA), Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) WA Opposition House Leader Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC), Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (WA) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Morton, F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Government Whip ND Opposition House Leader Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL), Oberle, Hon. Frank, Peace River (PC) Official Opposition Whip Olson, Hon.