Harry M. Sanders Truth and Reconciliation Notes for Ward 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 2018 Editor: CONTENTS Ian Urquhart JUNE 2018 • VOL

JUNE 2018 Editor: CONTENTS Ian Urquhart JUNE 2018 • VOL. 26, NO. 2 Graphic Design: Keystroke Design & Production Inc. Doug Wournell B Des, ANSCAD Features Association News www.keystrokedesign.com Printing by: 4 A Wilderness Adventure with 28 The 2018 Climb for Wilderness Topline Printing Inc. My Grandkids www.toplineprinting.ca 30 Introducing AWA’s Two New 8 The Hungry Bend Sandhills Conservation Specialists Printed on FSC Certified Paper 11 Linking Nature and Persons with 32 Moments That Matter: a Disability: Introducing Coyote Wendy Ryan’s life of defending Lake Lodge the Castle Wilderness 14 Trails, Sediment, and Aquatic Habitat: McLean Creek Wilderness Watch 16 Protecting & Recovering Wildlife in Canada 34 Updates 19 Comparing Mining Liability 36 Annual General Meeting Programs: Lessons for Alberta? ALBERTA WILDERNESS 21 The Public Lands Trifecta: ASSOCIATION Department Important Progress Made “Defending Wild Alberta through Where the Wild Things Are: Awareness and Action” 24 Reader’s Corner harnessing the power of citizen 37 Alberta Wilderness Association is scientists a charitable non-government In Memoriam: Charlie Russell, 39 organization dedicated to the Louise Guy Poetry Corner August 19, 1941 – May 7, 2018 26 completion of a protected areas donation, call 403-283-2025 or contribute online at AlbertaWilderness.ca. Wild Lands Advocate is published four times a year, by Alberta Wilderness Association. The opinions expressed Cover Photos by the authors in this publication are Cotton grass (Eriophorum species), not necessarily those of AWA. The featured prominently in this Vivian editor reserves the right to edit, reject or Pharis photo, is a common and co- withdraw articles and letters submitted. -

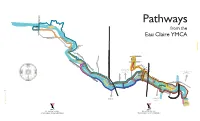

ECY Running Map:Layout 1.Qxd

Pathways from the Eau Claire YMCA GOING EAST 13. EDWORTHY PARK LOOP (15.1 km): Head west on the South side of the river beyond the CPR Rail 1. LANGEVIN LOOP (3.5 km): Go East on the South side of the river, past Centre Street underpass. way Crossing at Edworthy Park. Cross Edworthy Bridge to the North side of the river and head East. Cross over at the Langevin Bridge and head West. Return via Prince’s Island Bridge. Return to the South side via Prince’s Island Bridge. 2. SHORT ZOO (6.1 km): Go East on the South side of the river past Langevin Bridge to St George’s 14. SHOULDICE BRIDGE (20.4 km): Cross Prince’s Island Bridge to the North side of the river and head Island footbridge. Cross to the North side via Baines Bridge. Return on the North side heading West West to Shouldice Bridge at Bowness Road. Return the same way heading East. via Prince’s Island Bridge. 15. BOWNESS PARK via BOW CRESCENT (32.4 km): Follow North side of river going West from 3. LONG ZOO (7.6 km): Go East on the South side of the river over 9th Avenue Bridge. Travel through Prince’s Island to Bowness Road. Cross over Shouldice Bridge. Follow Bow Crescent, 70th Street, and the zoo to Baines Bridge. Return heading west on the North side of the river, crossing back via 48th Avenue to Bowness Park. Make loop of paved road (West) and return to YMCA same way. pathway around zoo and returning through Prince’s Island. -

Deerfoot Trail Study December 2020 Contents

Deerfoot Trail Study December 2020 Contents Background and Fast Facts ...............................................04 Study Goals, Objectives and Outcomes .......................06 Study Phases and Timeline ...............................................08 Identifying Challenges .......................................................12 What We Heard, What We Did ..........................................14 Developing Improvement Options................................18 Option Packages ...................................................................20 Option Evaluation ................................................................32 Recommended Improvements .......................................36 A Phased Approach for Implementation .....................44 Next Steps ...............................................................................52 2 The City of Calgary & Alberta Transportation | Deerfoot Trail Study Introduction The City of Calgary and Alberta Transportation In addition to describing the recommended are pleased to present the final recommendations improvements to the Deerfoot Trail corridor, this of the Deerfoot Trail Study. document provides a general overview of the study The principal role of the Deerfoot Trail within The process which involved a comprehensive technical City of Calgary is to provide an efficient, reliable, and program and multiple engagement events with safe connection for motor vehicle traffic and goods key stakeholders and city residents. movement within, to, and from the city. These key -

17 Ave. SE Corridor Study

Welcome to the 17 Avenue S.E. Corridor Study Open House Ask us about the study! Our team will be happy to talk with you about it. It will take about 10 minutes. You can also provide input at calgary.ca/17avestudy. calgary.ca/17avestudy | contact 311 17 Ave. S.E. Corridor Study Project(Stoney Trail to purposeEast City Limit) & goals The City is conductingTitle or headline a Myriad transportation Pro Light 60 ptStudy study Area on 17 Avenue S.E., between Stoney Trail andTitle the subhead east Myriad Pro city Light 48 limit pt (116 Street S.E.), to identify what the road will look like in the17 Ave. next S.E. 10-30 Corridor years. Study (Stoney Trail to East City Limit) Stoney Trail SE Trail Stoney 1 16 Street SE 1 16 Street 100 Street SE 100 Street 52 Street SE 52 Street Header and footer will have SE 68 Street 0.25” of bleed all the way around. SE 84 Street Title or headline Myriad Pro Light 60 pt Title subhead Myriad Pro Light 48 pt 17 Avenue SE Header and footer will have 0.25” of bleed all the way around. Study Area Urban Boulevard Parkway Deerfoot-Stoney Study Area Calgary City Limit Chestermere Study Area 17calgary.ca/17avestudycalgary.ca Avenue | contact 311 S.E. provides an important regional connection between Calgary and Chestermere. It is also identified in the Calgary Transportationcalgary.ca | contact 311 Plan as part of the Primary Transit and Primary Cycling Networks. Outcome: The study will result in a staged concept plan (short-, medium- and long-term) for all transportation modes (walking, cycling, taking transit and driving). -

From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View Versus the Narrow View

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-09-30 From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View Kuiken, Jacob Kuiken, J. (2014). From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26237 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1885 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View by Jacob Kuiken A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIAL WORK CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2014 © JACOB KUIKEN 2014 Abstract This dissertation looks back through the lens of a conflict that emerged during the development of social work education in Alberta, and captured by a dispute about the name of the school. The difference of a single word – welfare versus work – led through selected events in the history of social work where similar differences led to disputes about important matters. The themes of the dispute are embedded in the Western Tradition with the emergence of social work and its development at the focal point for addressing the consequences described as a ‘painful disorientation generated at the intersections where cultural values clash.’ In early 1966, the University of Calgary was selected as the site for Alberta’s graduate level social work program following a grant and volunteers from the Calgary Junior League. -

Ill CALGARY * CHAPT ■ R

Calgary NAIOP Downtown COMMEACIAL REAL ESTA T E Association OEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Ill CALGARY * CHAPT ■ R CITY OF CALGARY June 10, 2020 RECEIVED IN COUNCfL CHAMBER Mayor Nenshi and City Councillors P.O. Box 2100, Station M JUN 1 5 202~ 700 Macleod Trail South ITEM: 7 · 4-- ~-QS"83 Calgary, AB C:C T2P 2MS Di -s-re.., e u71Q1>...) CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT Re: Green Line Dear Mayor Nenshi and City Council, We would like to thank-you for the opportunity to appear before the Green Line Committee on June 1st to present our position and recommendations on the Green Line. Now that the Committee has forwarded Administration's proposal to the full City Council, the intent of this letter is to confirm our recommendations and ensure that all of Council is aware of them. As you are all aware, we are strong supporters of moving forward with the Green Line including a crossing of the Bow River, and we have and continue to recommend changes be made to ensure the entire Green Line maximizes its potential as a significant city building project. With that in mind we again propose the following recommendations which we would encourage Council to consider as amendments to the Administration recommendation made to the Green Line Committee. We would also like to reiterate our strong thanks and support for the changes made in the Eau Claire station area, and ask that Council formally adopt this station solution within their decision. Recommendation 1: Ensuring Successful Construction by Stage-Gating Stage 1 Given its size and scope, Council has prudently discussed the importance of cost management on the Green Line project. -

Macleod Trail Corridor Study TT2015-0183 Information Brochure ATTACHMENT 2

Macleod Trail Corridor Study TT2015-0183 Information Brochure ATTACHMENT 2 MACLEOD TRAIL CORRIDOR STUDY A balanced approach to transportation planning 2015-0626 calgary.ca | contact 311 Onward/ Providing more travel choices helps to improve overall mobility in Calgary’s transportation system. TT2015-0183 Macleod Trail Corridor Study - Att 2.pdf Page 1 of 12 ISC: Unrestricted Macleod Trail Corridor Study Information Brochure 100 YEARS OF MACLEOD TRAIL: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE Photo of Macleod Trail circa 1970. The City of Calgary, Corporate Records, Archives. Photo of Macleod Trail circa 2005. The City of Calgary, Corporate Records, Archives. Macleod Trail, as we know it today, has remained much the same since the 1960’s. It was, and continues to be, characterized by low-rise buildings accompanied by paved parking lots and poor infrastructure for pedestrians. The development of low-density land use and long distances between destinations or areas of interest has encouraged driving as the primary way for people to get to and from key destinations along Macleod Trail. What will Macleod Trail look like Because people will be living within walking or cycling distances to businesses and major activity centres over the next 50 years? (e.g. shopping centres), there will be a need for quality Many of the older buildings along Macleod Trail are sidewalks, bikeways, and green spaces that help enhance approaching the end of their lifecycle. Now is an safety of road users and improve the overall streetscape. opportune time to put in place conditions that will help guide a different type of land use and development along PEOPLE WILL HAVE ACCESS TO SAFE, Macleod Trail for the next 50 years. -

Regular Council Meeting

Town of Drumheller COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA Monday, July 20, 2020 at 4:30 PM Council Chamber, Town Hall 224 Centre Street, Drumheller, Alberta Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2.1. Agenda for July 20, 2020 Regular Council Meeting. Motion: That Council adopt the July 20, 2020 Regular Council Meeting agenda as presented. 3. MINUTES 4 - 7 3.1. Minutes for the July 6, 2020 Regular Council Meeting. Motion: That Council adopt the July 6, 2020 Regular Council Meeting minutes as presented. Regular Council - 06 Jul 2020 - Minutes 4. MINUTES OF MEETING PRESENTED FOR INFORMATION 8 - 9 4.1. Valley Bus Society July 2020 Meeting Minutes Motion: That Council accept the minutes of the July 2020 Valley Bus Society Meeting for information. Valley Bus Society July 2020 Meeting Minutes 5. DELEGATIONS 10 - 18 5.1. RCMP - Staff Sergeant Ed Bourque - Report Presentation 2020 Policing Survey Trends 6. ADMINISTRATION REQUEST FOR DECISION AND REPORTS 6.1. CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER 6.1.1. Covid-19 Town of Drumheller Update 19 - 21 6.1.2. Municipal Development Plan Bylaw 14.20 - Rezoning Amendment - Industrial Development to Industrial Development/Compatible Commercial Development Please Note: A Public Hearing will be held Tuesday August 4, 2020. Motion: That Council give first reading to Municipal Development Plan Bylaw No.14.20 to amend Municipal Development Plan Bylaw 11.08 for the Town of Drumheller. Drumheller MDP Amending Bylaw 14.20 22 - 24 6.1.3. Land Use Bylaw 15.20 - Uses and Rules for Direct Control District Please Note: A Public Hearing will be held Tuesday August 4, 2020. -

Stand Alone Office Building for Lease 431 - 58Th Avenue Se, Calgary, Ab

STAND ALONE OFFICE BUILDING FOR LEASE 431 - 58TH AVENUE SE, CALGARY, AB N 4 Street SE P P 58 Avenue SE Dining Major Public Transit Services Thoroughfares Accessibility Petro Canada Subway 58th Avenue SE Serviced by Bus Wholesale Foods Tim Hortons Blackfoot Trail Routes: 66, 72, 73 TD Canada Trust Wendy’s Macleod Trail Oriental Phoenix RBC Royal Bank Gaucho 7-Eleven Alexi Olcheski, Principal Paul McKay, Vice President Eric Demaere, Associate 403.232.4332 587.293.3365 587.293.3366 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] © 2018 Avison Young Real Estate Alberta Inc. All rights reserved. E. & O.E.: The information contained herein was obtained from sources which we deem reliable and, while thought to be correct, is not guaranteed by Avison Young. 431 - 58TH AVENUE SE, CALGARY, AB Particulars estled on 58th Avenue SE between the major Available Space: 5,048 SF (Demisable) Nthouroughfares of Blackfoot Trail and Macleod Trail, this rare stand alone office space is a one-of-a Demising A. 1,528 SF kind opportunity for various tenants. Whether the Options: B. 2,099 SF use is medical or business, this space is guaranteed to be the perfect location to build and expand your C. 2,949 SF business. Within a 3 km radius, the 2017 daytime D. 3,520 SF population was 58,467, with 24,000 vehicles per day (VPD) on 58th Avenue SE and 57,000 VPD on Rental Rates: Market Blackfoot Trail SE. Op. Costs: $12.76 PSF (2018 est.) Zoning: I-G (Industrial-General) Occupancy: 30 days Term: 5 - 10 years Highlights - Located on the southwest corner of 58th Avenue and 4th Street SE - Minutes away from Chinook Centre, Calgary’s largest enclosed mall (1.2M GLA) - 23 surface parking stalls at the rear of the property - High quality interior finishes - Features include showers, washing machine, and dryer Alexi Olcheski, Principal Paul McKay, Vice President Eric Demaere, Associate 403.232.4332 587.293.3365 587.293.3366 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] © 2018 Avison Young Real Estate Alberta Inc. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Alberta Hansard Thursday, November 4, 2010 Issue 39 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Third Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL) Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (WA), Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) WA Opposition House Leader Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC), Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Official Opposition Deputy Leader, Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (WA) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Morton, Hon. F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Government Whip ND Opposition House Leader Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL), Oberle, Hon. -

3200, 17Th Avenue SE Calgary, Alberta

FOR LEASE Multiple CRU’s 500 ± sf - 10,000 ± sf 3012 - 3200, 17th Avenue SE Calgary, Alberta Property Features Prime retail units available immediately in the vibrant business district of 17th Avenue Tenant mix includes TD Canada Trust, Shopper’s Drug Mart, Mac’s, Co-op Liqour, Salvation Army, Aaron’s Furniture, Forest Lawn Medical Clinics and, many more Ample on-site customer parking with easy access and egress Minutes to the Calgary Downtown Core and Deerfoot Trail as well as 10 minutes away form the Calgary International Airport Largest multi-tenant shopping centre in this trade area with access to over 42,000 vehicles per day (2016), via 17th avenue Please contact agents for more information Brian West, Senior Associate 833 34 Avenue SE [email protected] Calgary AB, T2G 4Y9 (403) 984.6303 Barlow Trail SE Barlow Trail FOR LEASE Multiple CRU’s 500 ± sf - 10,000 ± sf Deerfoot Trail 17 Ave SE 16 Avenue SE 28 Street SE 17 Avenue SE 17 Avenue SE Property Details District: Forest Lawn Term: 5 -10 Years Zoning: C-C2 Signage: Fascia & Pylon Op Costs: $10.76 (Est. 2017) Traffic Count: 42,000 VPD (17th Avenue) Net Rent: Market Availability: Immediately Parking: 400 Stalls (Ample Parking) Brian West, Senior Associate 833 34 Avenue SE [email protected] Calgary AB, T2G 4Y9 (403) 984.6303 FOR LEASE Multiple CRU’s 500Site ± sf - Plan10,000 ± sf Unit 21 H & I Dr. Yoshida Dr. Unit 21 C-6&5 Unit 4 & 5 Unit 11 Unit 2 V&T Meats Dr. Lukenchuk Dr. Future Nails Future Chicago Pizza Momma Jeans TopTreme Hair TopTreme Unit 21 Food & Spice Nature’s A &