Part 2: the Design Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elaine Knobel-Forbes

Homefields, May Street, Great Chishill, Royston, Hertfordshire, SG8 8SN. 09 November 2020 Uttlesford District Council Planning Department Council Offices London Road Saffron Walden CB11 4ER Dear Sirs, Planning Application Reference: UTT/20/1798/FUL Proposal: Erection of 1 no. Agricultural Barn Location: Langley Park Farm, Langley Lower Green, Langley CB11 4SB I have been made aware of the proposal to erect a new barn at Langley Park Farm and whilst I have every respect for the necessity of farmers to manage their business, it has been suggested locally that this barn is primarily a storage hub and is grossly disproportionate in size to the land actually owned. There is no information on the application in respect of traffic movements, traffic management or designated routes for vehicles visiting or leaving the location. It is also my understanding that an additional large barn, with planning permission, is already under construction on land adjoining the proposed barn at Langley Park Farm, which will also have high volumes of HGV traffic, particularly during harvest time. The application makes no suggestion of constructing a new access at the junction with Park Lane to accommodate the turning area of large articulated vehicles, by experience, some with trailers. Clearly, the highway at this junction has restricted turning capacity and is not currently constructed in a way to support the aggressive friction between the vehicle tyres and the road. No vehicle tracking has been shown for vehicles entering or exiting the farm. Page 1 of 10 Should the vehicles visiting or leaving Langley Park Farm choose to turn north towards Little Chishill in Cambridgeshire they will need to navigate through very narrow lanes not designed to accommodate such sized vehicles. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2016, East of England

East of England Register 2016 HERITAGE AT RISK 2016 / EAST OF ENGLAND Contents Heritage at Risk III North Norfolk 44 Norwich 49 South Norfolk 50 The Register VII Peterborough, City of (UA) 54 Content and criteria VII Southend-on-Sea (UA) 57 Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Suffolk 58 Reducing the risks XI Babergh 58 Key statistics XIV Forest Heath 59 Publications and guidance XV Mid Suffolk 60 St Edmundsbury 62 Key to the entries XVII Suffolk Coastal 65 Entries on the Register by local planning XIX Waveney 68 authority Suffolk (off) 69 Bedford (UA) 1 Thurrock (UA) 70 Cambridgeshire 2 Cambridge 2 East Cambridgeshire 3 Fenland 5 Huntingdonshire 7 South Cambridgeshire 8 Central Bedfordshire (UA) 13 Essex 15 Braintree 15 Brentwood 16 Chelmsford 17 Colchester 17 Epping Forest 19 Harlow 20 Maldon 21 Tendring 22 Uttlesford 24 Hertfordshire 25 Broxbourne 25 Dacorum 26 East Hertfordshire 26 North Hertfordshire 27 St Albans 29 Three Rivers 30 Watford 30 Welwyn Hatfield 30 Luton (UA) 31 Norfolk 31 Breckland 31 Broadland 36 Great Yarmouth 38 King's Lynn and West Norfolk 40 Norfolk Broads (NP) 44 II East of England Summary 2016 istoric England has again reduced the number of historic assets on the Heritage at Risk Register, with 412 assets removed for positive reasons nationally. We have H seen similar success locally, achieved by offering repair grants, providing advice in respect of other grant streams and of proposals to bring places back into use. We continue to support local authorities in the use of their statutory powers to secure the repair of threatened buildings. -

Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills at Risk Simon Hudson

Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills at Risk Simon Hudson Discovering Mills East of England Building Preservation Trust A project sponsored by 1 1. Introductory essay: A History of Mill Conservation in Cambridgeshire. page 4 2. Aims and Objectives of the study. page 8 3. Register of Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills page 10 Grade I mills shown viz. Bourn Mill, Bourn Grade II* mills shown viz. Six Mile Bottom Windmill, Burrough Green Grade II mills shown viz. Newnham Mill, Cambridge Mills currently unlisted shown viz. Coates Windmill 4. Surveys of individual mills: page 85 Bottisham Water Mill at Bottisham Park, Bottisham. Six Mile Bottom Windmill, Burrough Green. Stevens Windmill Burwell. Great Mill Haddenham. Downfield Windmill Soham. Northfield or Shade Windmill Soham. The Mill, Elton. Post Mill, Great Gransden. Sacrewell Mill and Mill House and Stables, Wansford. Barnack Windmill. Hooks Mill and Engine House Guilden Morden. Hinxton Watermill and Millers' Cottage, Hinxton. Bourn Windmill. Little Chishill Mill, Great and Little Chishill. Cattell’s Windmill Willingham. 5. Glossary of terms page 262 2 6. Analysis of the study. page 264 7. Costs. page 268 8. Sources of Information and acknowledgments page 269 9. Index of Cambridgeshire Watermills and Windmills by planning authority page 271 10. Brief C.V. of the report’s author. page 275 3 1. Introductory essay: A History of Mill Conservation in Cambridgeshire. Within the records held by Cambridgeshire County Council’s Shire Hall Archive is what at first glance looks like some large Victorian sales ledgers. These are in fact the day books belonging to Hunts the Millwrights who practised their craft for more than 200 years in Soham near Ely. -

South Cambridgeshire District Council

SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL REPORT TO: Planning Committee 7th April 2010 AUTHOR/S: Executive Director (Operational Services) / Corporate Manager (Planning and Sustainable Communities) S/0201/10/F – Great and Little Chishill Dwelling at land to the West of 24 Barley Road for Mr R J Parry Recommendation: Delegated Approval Date for Determination: 8 April 2010 Notes: This Application has been reported to the Planning Committee for determination as the recommendation to approve conflicts with the recommendation of the Parish Council. Site and Proposed Development 1. The application site is land to the West of No. 24 Barley Road and lies adjacent to the Great and Little Chishill Conservation Area. No 24 is a bungalow with permission to extend into the loft space to create a dormer bungalow. It has an existing access at the East end of the frontage and a detached garage in the South East corner of the site. The land levels on site slope down to the West and in general in the area they slope down to the West and South, meaning that the road to the South is sited lower than the existing properties. To the West of the site is No.26 Barley Road, a detached dwelling sited on slightly lower land, to the North (rear) of the site is the garden of Stepaside Cottage, a Grade II Listed Building, which runs along the rear boundary of Nos. 22, 24 and 26 Barley Road, and to the South (front) of the site is Barley Road and open countryside beyond. 2. The planning application seeks permission for the erection of a single dormer bungalow with associated access and parking. -

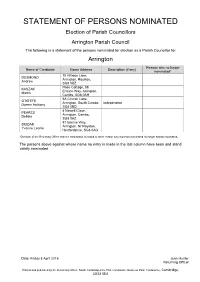

Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish Councillors Arrington Parish Council The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Arrington Reason why no longer Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) nominated* 10 Hillside Lane, DESMOND Arrington, Royston, Andrew SG8 0BZ Rose Cottage, 88 KASZAK Ermine Way, Arrington, Martin Cambs, SG8 0AH 9A Church Lane, O`KEEFE Arrington, South Cambs, Independent Darren Anthony SG8 0BD 4 Newell Close, PEARCE Arrington, Cambs, Debbie SG8 0AZ 51 Ermine Way, SIUDAK Arrington, Nr Royston, Yvonne Leonie Hertfordshire, SG8 0AG *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Date: Friday 8 April 2016 Jean Hunter Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, South Cambridgeshire Hall, Cambourne Business Park, Cambourne, Cambridge, CB23 6EA STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish Councillors Cambourne Parish Council The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Cambourne Reason why no longer Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) nominated* 24 Foxhollow, Great CROCKER Cambourne, Cambridge, Simon Nicholas CB23 5HW 20 Brookfield Way, GAVIGAN Lower Cambourne, Patrick James Cambridgeshire, CB23 5ED 108 Greenhaze Lane, HUDSON Great Cambourne, Tom CB23 5BH 38, Lancaster Gate, MEHBOOB Upper Cambourne, Ghazala CB23 6AT 3 Langate Green, Great O`DWYER Cambourne, Cambridge, Joseph CB23 5AE 1 Whitley Road, Upper PATEL Cambourne, Jey Cambridgeshire, CB23 6AS 5, Chervil Way, Great POULTON Cambourne, Ruth Cambridgeshire, CB23 6BA SAWFORD 139 Jeavons Lane, Jeni Cambourne, CB23 5FA 14 Spar Close, Lower THOMPSON Cambourne, Greg Robert Cambridgeshire, CB23 6FG *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

Mineral Resources Map for Essex

500 000 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 906 00000 10 20 30 40 NW LIMIT OF ANGLIAN SE BGS publications covering Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock (5) and the ICE SHEET Inferred subcrop of London Boroughs of Barking & Dagenham (3), Havering (4), Redbridge (2) Carboniferous Limestone and Waltham Forest (1) beneath Mesozoic rocks Foxearth (Pt, Sg) Glacial sand and gravel Report 97 Report 118 250 205 206 Lowestoft Till Hoe Lane (Sg) Kesgrave Plateau Buried soil horizon Glaciofluvial sand and gravel reworking Report 133 Report 82 Report 68 report 85 Report 11 Report 8 Glacial sand B EDR and gravel Head Gravel Thin Brickearth Little Chishill 1 O CK 222 223 ESSEX River terrace PEDL36 Alluvium Crag River Terraces CANUK Crag Great Chesterford (Sg) Saltmarsh Report 104 Report 109 Report 16 Report 102 Report 10 Report 14 (comprising Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock, Tidal Flats Sea Level Walden Road (Ch) Sub-alluvial Sand London Boroughs of Barking & Dagenham, Lambeth Group and Gravel Buried Channel (Woolwich and Report 112 Report 46 Report 52 Report 6 Report 2 Report 7 224 Reading Beds) Havering, Redbridge and Waltham Forest) Thames Group (London Clay, Sub-alluvial gravel Chalk (High purity) Harwich Formation) Buried Channel Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Thanet Sand Formation Report 67 Report 66 Report 13 Report 4 Regional and Local Planning Rectory Farm (Sg) 40 40 2 Little Walden Road (Ch) Mineral Resources 00 Goldingham Hall (Sg) 239 240 241 242 Grange Farm (Sg) Report 34 Scale 1:100 000 Report 43 Bulmer (Cl) Schematic section showing form and relationship of mineral resources in Essex (not to scale) 1 2 Compiled by A.J. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2014, East of England

2014 HERITAGE AT RISK 2014 / EAST OF ENGLAND Contents Heritage at Risk III Norfolk Broads (NP) 48 North Norfolk 48 Norwich 54 The Register VII South Norfolk 56 Content and criteria VII Peterborough, City of (UA) 59 Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Southend-on-Sea (UA) 63 Reducing the risks X Suffolk 64 Key statistics XIII Babergh 64 Publications and guidance XIV Forest Heath 65 Ipswich 66 Key to the entries XVI Mid Suffolk 66 Entries on the Register by local planning XVIII St Edmundsbury 68 authority Suffolk Coastal 71 Waveney 75 Bedford (UA) 1 Thurrock (UA) 76 Cambridgeshire 2 Cambridge 2 East Cambridgeshire 3 Fenland 6 Huntingdonshire 7 South Cambridgeshire 10 Central Bedfordshire (UA) 15 Essex 17 Braintree 17 Brentwood 18 Chelmsford 19 Colchester 20 Epping Forest 21 Harlow 23 Maldon 23 Tendring 24 Uttlesford 27 Hertfordshire 28 Broxbourne 28 Dacorum 29 East Hertfordshire 29 North Hertfordshire 30 St Albans 33 Stevenage 33 Three Rivers 33 Watford 33 Welwyn Hatfield 34 Luton (UA) 34 Norfolk 35 Breckland 35 Broadland 40 Great Yarmouth 42 King's Lynn and West Norfolk 44 II EAST OF ENGLAND Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Over the past year we have focused much of our effort on assessing listed Places of Worship, and visiting those considered to be in poor or very bad condition as a result of local reports. -

December 2020

DecemberVillage /January 2020/21 Web 2 Virtual Christingle Service Sunday 6 December 4pm Come and join us online as we tell the story of Christingle. We will be assembling our Christingle oranges in the service, so if you'd like to join in, you'll need to gather: an orange, a small candle, some tin foil, red tape, cocktail sticks and some sweets or dried fruits. We'll be singing some favourite Christingle songs. Hope to see you! Find the Youtube link on the Icknield Way Parish website. VWDec/Jan2021.qxp_Layout 2 25/11/2020 20:40 Page 4 1 VWDec/Jan2021.qxp_Layout 2 25/11/2020 20:40 Page 5 2 VWDec/Jan2021.qxp_Layout 2 25/11/2020 20:40 Page 6 Parish News from Anand,our Rector Dear all I trust you are all keeping safe and well. I want to thank all the Parish members who attended the Annual Parochial Church Council meeting in October. Thank you all so much for your support of my ministry. Our heartfelt thanks go out to Viv Rogers for her services as Parish Warden for more than two years who stepped down recently. Jon Wayper has stepped in as our new Parish Warden and Mel Chandler has kindly agreed to continue as Deputy Parish Warden. A warm welcome to both Jon and Mel. We also welcomed David Wilkinson and Jane Fouche as our new Parochial Church Council members and said farewell to Alison Wilkinson, Emily Brown and Ned Tozer and thanked them for their services. Let us hope that the second lockdown will not be extended and that the eagerly anticipated vaccine will be available soon! During these unprecedented times we have had to adapt to new ways of doing things, including our Parish producing online recorded services with the help of our talented team of musicians, singers and technicians, to whom I am very grateful. -

The Hundred Parishes HEYDON

The Hundred Parishes An introduction to HEYDON Location: 4 miles east of Royston. Ordnance Survey grid square: TL4340. Postcode: SG8 8PN. Access: north off B1039. Buses: Infrequent – 31 Cambridge – Barley; 43 Royston – Chrishall. County: Cambridgeshire. District: South Cambridgeshire. Population: 243 in 2011. Heydon village stands on the high escarpment of chalk and glacial till (also known as boulder clay) that generally defines the boundary between Essex and Cambridgeshire. From a height of about 140 metres (460 feet) above sea level, the parish sweeps down to about 40 metres (130 feet) at its northern boundary. Like its larger neighbouring parish, Great and Little Chishill, Heydon moved from Essex to Cambridgeshire as part of a boundary change in 1895. Archaeological evidence suggests that this was an important location nearly 2,000 years ago. The parish is crossed by the Icknield Way, a broad and ancient trackway that runs from Norfolk to Wiltshire, and also by Bran Ditch, a 3-mile defensive earthwork. The date of origin of both features is uncertain. Bran Ditch, shown here, runs in an almost straight line northwest from Heydon village towards Fowlmere and is believed to be part of the defensive network known as the Cambridgeshire Dykes. Bran Ditch and adjacent sites were scheduled as an Ancient Monument only in 2012. The English Heritage citation explains that the ditch and bank is probably post-Roman, probably Anglo-Saxon, built by the early Germanic settlers to deter British incursion from the west. The earthwork is followed for some distance out of Heydon village by the Harcamlow Way long-distance path. -

Mineral Resources Report for Essex

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Essex (comprising Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock and the London Boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Redbridge and Waltham Forest) British Geological Survey Commissioned Report CR/02/127N A J Bloodworth, S J Mathers, A J Benham, M A Shaw, D G Cameron, N A Spencer, D J Evans, G K Lott and D E Highley. Keyworth, Nottingham 2002 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORT CR/02/127N Mineral Resources Series Mineral Resource Information for Development Plans: Essex (comprising Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock and the London Boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Redbridge and Waltham Forest) A J Bloodworth, S J Mathers, A J Benham, M A Shaw, D G Cameron, N A Spencer, D J Evans, G K Lott and D E Highley. This report accompanies the 1:100 000 scale map: Essex (comprising Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock and the London Boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Redbridge and Waltham Forest) Bibliographical reference: A J Bloodworth, S J Mathers, A J Benham, M A Shaw, D G Cameron, N A Spencer, D J Evans, G K Lott and D E Highley. 2002. Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning: Essex (comprising Essex, Southend-on-Sea, Thurrock and the London Boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Redbridge and Waltham Forest). BGS Commissioned Report CR/02/127N. All photographs copyright © BGS Front cover photo: Kesgrave Formation sand being worked at Martell’s Quarry near Colchester. BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey Offices Sales Desk at the Survey headquarters, Keyworth, Nottingham. -

The Parish of the Icknield Way Villages Profile

The Parish of the Icknield Way Villages Profile Welcome to our parish. Thank you for being interested in us. All Together…… God’s work in progress The Parish of the Icknield Way Villages (cont’d) We are praying that God is preparing a new leader for us. We believe that you, too, will be praying about whether that person might be you. Who are we? We are a single rural parish comprising seven villages in north-west Essex. Our last rector consolidated the work of forming us into one parish, and he leaves us as a warm, hospitable Christian community in good heart and harmony. We believe that God is at work here. He has a plan for us and wants us to join him in his work and we have faith in the power of the Holy Spirit to help us. We have seen our congregations expand and we long to see them grow further, spiritually as well as numerically. We feel we must do more to encourage young families, to deepen their faith in the Lord Jesus or to meet him for the first time. We realise we need patience and gentleness as we work together to build a church where God will be very evident. We seek to follow the vision of the Diocese of Chelmsford, to be a Transforming Presence here (www.transformingpresence.org.uk), to be distinctive in our Christian faith and outreach. We aim to be… Christ-centred Prayerful Faithful to scripture Loving Welcoming Accepting all Sharing fellowship together 2 All Together……. God’s work in progress The Parish of the Icknield Way Villages (cont’d) Who are we looking for? Someone who can… ..lead us in our efforts as we focus on these 3 overlapping strands: Evangelism Pastoral care Use/adaptation of our buildings. -

Great Chishill

Great Chishill Settlement Size Settlement Category Adopted LDF Core Proposed Submission Strategy (2007) Local Plan (2013) Infill Village Infill Village Source: South Cambridgeshire District Council Population Dwelling Stock (mid-2012 estimate) (mid-2012 estimate) 540 220 *dwellings stock figure for Great and Little Chishill Source: Cambridgeshire County Council Transport Bus Service: A) Summary Bus Service Monday – Friday Saturday Sunday Cambridge / Market Town Frequency Frequency Frequency To / From Cambridge 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service To / From Royston 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service To / From Saffron Walden 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service B) Detailed Bus Service Monday - Friday Cambridge / Market Service 7:00-9:29 9:30-16:29 16:30-18:59 19:00-23:00 Town 31 1 Bus No Service No Service No Service To Cambridge 334 (Fri) No Service 1 Bus No Service No Service 31 No Service 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service From Cambridge 334 (Fri) No Service 1 Bus No Service No Service To Royston 43 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service No Service From Royston 43 No Service 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service To Saffron Walden 444* 1 Bus No Service No Service No Service From Saffron 444* No Service 1 Bus No Service No Service Walden *Schooldays only Services and Facilities Study March 2014 Great Chishill Page 255 Saturday Cambridge / Market Service 7:00-9:29 9:30-16:29 16:30-18:59 19:00-23:00 Town 31 1 Bus No Service No Service No Service To Cambridge 334 (Fri) No Service No Service No Service No Service 31 No Service 1 Bus 1 Bus No Service From Cambridge 334 (Fri) No Service No Service No Service No Service To