4 Accordingly, Defendants Deny That They Infringe Plaintiffs' Alleged Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Stamos Helps Inspire Youngsters on WE

August 10 - 16, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad John Stamos H K M F E D A J O M I Z A G U 2 x 3" ad W I X I D I M A G G I O I R M helps inspire A N B W S F O I L A R B X O M Y G L E H A D R A N X I L E P 2 x 3.5" ad C Z O S X S D A C D O R K N O youngsters I O C T U T B V K R M E A I V J G V Q A J A X E E Y D E N A B A L U C I L Z J N N A C G X on WE Day R L C D D B L A B A T E L F O U M S O R C S C L E B U C R K P G O Z B E J M D F A K R F A F A X O N S A G G B X N L E M L J Z U Q E O P R I N C E S S John Stamos is O M A F R A K N S D R Z N E O A N R D S O R C E R I O V A H the host of the “Disenchantment” on Netflix yearly WE Day Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bean (Abbi) Jacobson Princess special, which Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Luci (Eric) Andre Dreamland ABC presents Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Elfo (Nat) Faxon Misadventures King Zog (John) DiMaggio Oddballs 1 x 4" ad Friday. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

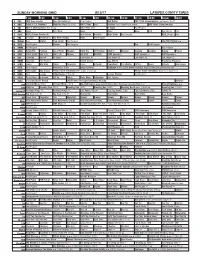

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

Rob Kardashian, His Then-Fiancée Blac Chyna and Their Pregnancy/Newborn Daughter, for One Season

The Neoliberal Life of the “Failing” Kardashian: Robert Kardashian On (Not) Keeping up with the Kardashians Leah Groenewoud (Third year, RLCT/GEND Major) GEND 3076 Dr. Wendy Peters April 5, 2015 Introduction Keeping up with the Kardashians (KUWTK) is a reality television show that follows the lives of the Kardashian family – a famous, upper-class Californian family consisting of Kris Jenner (the Kardashians’ mother and business manager), her (now ex-) husband Caitlyn Jenner and their children. Kris’ children include Kourtney, Kim, Khloe and Robert Kardashian, and Kris and Caitlyn have two younger children, Kendall and Kylie Jenner. Rob & Chyna is a reality TV spin-off of KUWTK which followed Rob Kardashian, his then-fiancée Blac Chyna and their pregnancy/newborn daughter, for one season. This paper will employ a textual analysis of these two shows to analyze how Robert Kardashian’s life and life choices are portrayed as personal failures. Conversations and information about Rob – in the 12 episodes across 6 seasons of KUWTK, and 6 episodes of season 1 of Rob & Chyna which I studied – are consistently about how Rob must change, and that he is not happy or successful the way he is. Robert Kardashian is consistently portrayed as a failure, which this paper will clarify to mean a neoliberal failure. This paper will analyze the neoliberal logics of the narratives about Robert and the way he lives, including narratives about his health, his (lack of) independence and self-esteem, his marriageability and employability.i I will conclude with an analysis of how KUWTK and Rob & Chyna facilitate a ‘panoptic existence’ for Rob, in which his family, the viewers and even himself surveil and regulate Rob. -

Using Game Design and Game Elements in the EFL Classroom ======

>GAMIFICATION ========================================================== >Using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom_ ========================================================== Figure 1 Alien by Illaria Bernareggi / The Noun Project Gilles Glod professeur-candidat Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Declaration of originality I certify that all material contained in this travail de candidature is my own work. All source material is clearly acknowledged as and when it occurs in the references, as well as in the list of works cited. Luxembourg, 4th November 2017 2 Gilles Glod professeur-candidat au Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Gamification: using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom Bonnevoie, 2017 3 Abstract Research objectives This thesis discusses the ways in which one of the basic human instincts – the urge to play – can be used in an EFL classroom to improve learners’ motivation, social skills and willingness to engage in language learning. My thesis focuses on three major aspects. First, in my lessons, I have implemented games as well as features that often form the core of games, such as rules of play, experience points, achievements, and the levelling up and customization of an avatar. The learners see their progress mirrored within the paradigm of role-playing games: their activities in the classroom inform the de- velopment of their in-game avatars and unlock real-life abilities and rewards. Second, I analyse which games and aspects of gamification are conducive to the creation of a ludic space. While the use of tablets is not the core focus of this thesis, I have worked with pedagogical and language-learning games designed for tablets as well as classroom games designed to use tablets as one of their central features. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Best Enjoyed As Property, Shoe and Hairdo Porn.”

”Best enjoyed as property, shoe and hairdo porn.” Creating New Vocabulary in Present-Day English: A Study on Film-Related Neologisms in Total Film Rauno Sainio Tampere University School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Philology Pro Gradu Thesis May 2011 ii Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö SAINIO, RAUNO: ”Best enjoyed as property, shoe and hairdo porn.” Creating New Vocabulary in Present-Day English: A Study on Film-Related Neologisms in Total Film Pro gradu -tutkielma, 135 sivua + liite (6 sivua) Kevät 2011 Tämän pro gradu -tutkielman tarkoituksena oli tutustua eri menetelmiin, joiden avulla englannin kielen sanastoa voidaan laajentaa. Lähdekirjallisuudesta kerättyä tietoa käsiteltiin tutkielman teoriaosuudessa, minkä jälkeen empiirinen osuus selvitti, kuinka kyseisiä menetelmiä sovelletaan käytännössä nykyenglannissa. Tämän selvittämiseksi käytiin manuaalisesti läpi korpusaineisto, joka koostui isobritannialaisen Total Film -elokuvalehden yhden vuoden aikana julkaistuista numeroista. Elokuvajournalismissa käytettävä kieli valittiin tutkimuksen kohteeksi kirjoittajan henkilökohtaisen kiinnostuksen vuoksi sekä siksi, että elokuva on paitsi merkittävä, myös jatkuvasti kehittyvä taiteen ja populaarikulttuurin muoto. Niinpä tämän tutkielman tarkoitus on myös tutustuttaa lukija sellaiseen sanastoon, jota alaa käsittelevä lehdistö nykypäivänä Isossa-Britanniassa käyttää. Korpuksen pohjalta koottu, 466 elokuva-aiheista uudissanaa käsittävä sanaluettelo analysoitiin -

Pegi Annual Report

PEGI ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 2 CHAPTER 1 The PEGI system and how it functions 4 AGE CATEGORIES 5 CONTENT DESCRIPTORS 6 THE PEGI OK LABEL 7 PARENTAL CONTROL SYSTEMS IN GAMING CONSOLES 7 STEPS OF THE RATING PROCESS 9 ARCHIVE LIBRARY 9 CHAPTER 2 The PEGI Organisation 12 THE PEGI STRUCTURE 12 PEGI S.A. 12 BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 12 THE PEGI CONGRESS 12 PEGI MANAGEMENT BOARD 12 PEGI COUNCIL 12 PEGI EXPERTS GROUP 13 COMPLAINTS BOARD 13 COMPLAINTS PROCEDURE 14 THE FOUNDER: ISFE 17 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATOR: NICAM 18 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATOR: VSC 20 PEGI IN THE UK - A CASE STUDY? 21 PEGI CODERS 22 CHAPTER 3 The PEGI Online system 24 CHAPTER 4 PEGI Communication tools and activities 28 Introduction 28 Website 28 Promotional materials 29 Activities per country 29 ANNEX 1 PEGI Code of Conduct 34 ANNEX 2 PEGI Online Safety Code (POSC) 38 ANNEX 3 The PEGI Signatories 44 ANNEX 4 PEGI Assessment Form 50 ANNEX 5 PEGI Complaints 58 1 INTRODUCTION Dear reader, We all know how quickly technology moves on. Yesterday’s marvel is tomorrow’s museum piece. The same applies to games, although it is not just the core game technology that continues to develop at breakneck speed. The human machine interfaces we use to interact with games are becoming more sophisticated and at the same time, easier to use. The Wii Balance Board™ and the MotionPlus™, Microsoft’s Project Natal and Sony’s PlayStation® Eye are all reinventing how we interact with games, and in turn this is playing part in a greater shift. -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Ryan's Roses and Media Exposure Through the Lens of Cultivation

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 39-51 Ryan’s Roses and Media Exposure through the Lens of Cultivation Wesley Hernandez Abstract This paper undertakes an extensive analysis of the Los Angeles radio program, Ryan’s Roses. Ryan’s Roses showcases adultery and toxic relationships in an entertaining fashion. Little research exists regarding the extent to which radio talk shows affect an individual’s engagement in romantic relationships. Studies from cultivation theory, media exposure, and radio were engaged to develop a framework for gauging negative behavioral effects in consistent listeners of the show. The subsequent analysis provides structural support for the claim that heavy listening exposure to Ryan’s Roses perpetuates distorted views of romantic relationships. Within the field of communication studies, research on cultivation effects has successfully been conducted in various parts of the world (Hetsroni & Tukachinsky, 2006). However, there exists very little research that examines the effects radio programs on people’s perception of romantic relationships. In this regard, a particular radio program that is worthwhile to explore is Ryan’s Roses. Hosted by internationally known celebrity Ryan Seacrest, Ryan’s Roses presents interpersonal conflicts among heterosexual couples whereby the girlfriend, or wife, believes that her romantic partner is secretly engaging in intimate behaviors with another woman (Seacrest, 2015). Given that a substantial amount of men commit adultery, the thematic aim of the show is to deceive, shame, and publicly embarrass such men on live radio. Ryan’s Roses follows a specific routine that consistently leads to the same dramatic conclusion, that is, a male individual having to explain his immoral and adulterating actions to his romantic partner. -

Fictious Flattery: Fair Use, Fan Fiction, and the Business of Imitation

Intellectual Property Brief Volume 8 Issue 2 Article 1 2016 Fictious Flattery: Fair Use, Fan Fiction, and the Business of Imitation Mynda Rae Krato George Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Krato, Mynda Rae (2016) "Fictious Flattery: Fair Use, Fan Fiction, and the Business of Imitation," Intellectual Property Brief: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief/vol8/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intellectual Property Brief by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fictious Flattery: Fair Use, Fan Fiction, and the Business of Imitation This article is available in Intellectual Property Brief: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief/vol8/iss2/1 FICTITIOUS FLATTERY: FAIR USE, FANFICTION, AND THE BUSINESS OF IMITATION Mynda Rae Krato INTRODUCTION ............. 92 L Background............................................................. 94 A. Foundational Statutory and Case Law..................................94 B. Fanfiction Case Law..............................................96 C. Popular Culture and the Power of Fandoms ............................. -

UNIVERSAL BROADBAND ADOPTION: How to Get There, and Why America Needs It

UNIVERSAL BROADBAND ADOPTION: How To Get There, And Why America Needs It Universal Broadband Adoption: How to Get There, And Why America Needs It TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................9 PART ONE – THE DIGITAL IMPERATIVE: CLOSING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE.....................................................11 Chapter 1 – The Importance of Broadband to Minorities............................................................12 Why Connecting the Unconnected to Broadband Helps Everyone on the Network.............................12 How People of Color Use Broadband.............................................................................................13 8 Reasons to Adopt Broadband Now..............................................................................................14 Minorities Embrace Internet Access in the Palm of their Hands.....................................................16 How to Sustain Innovation in the Wireless Sector...........................................................................17 Further Evidence of a Looming Spectrum Crisis.............................................................................18 Chapter 2 – Minorities and The Digital Divide.............................................................................19 Why Broadband is the Top Civil Rights Issue of the 21st Century...................................................19 Why the Unconnected are Second-Class