Roger Pulvers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

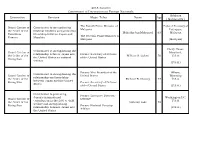

2018 Autumn (PDF)

2018 Autumn Conferment of Decoration on Foreign Nationals Address Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age ( Nationality ) The Fourth Prime Minister of Federal Territory of Grand Cordon of Contributed to strengthening Malaysia Putrajaya, the Order of the bilateral relations and promoting Mahathir bin Mohamad 93 Malaysia Paulownia friendship between Japan and The Seventh Prime Minister of Flowers Mayalsia Malaysia (Malaysia) Chevy Chase, Contributed to strengthening the Grand Cordon of Maryland, relationship between Japan and Former Secretary of Defense the Order of the William S. Cohen 78 U.S.A. the United States on national of the United States Rising Sun defense (U.S.A.) Former Vice President of the Wilson, Contributed to strengthening the Grand Cordon of United States Wyoming relationship and friendship the Order of the Richard B. Cheney 77 U.S.A. between Japan and the United Rising Sun Former Secretary of Defense States of the United States (U.S.A.) Contributed to promoting Former Executive Director, Japan's international Washington DC, Grand Cordon of UNICEF contribution in the field of child U.S.A. the Order of the Anthony Lake 79 welfare and strengthening Rising Sun Former National Security relationship between Japan and (U.S.A.) Advisor the United States 2018 Autumn Conferment of Decoration on Foreign Nationals Former Vice Prime Minister Hydra, Contributed to strengthening Former Minister of Interior Grand Cordon of Alger, bilateral relations and promoting and Local Governments the Order of the Noureddine Yazid Zerhouni 81 Algeria -

Trauma and Recovery in Children's Books About Natural Disasters

VOL. 50, NO.1 JANUARY 2012 FEATURED ARTICLES Surviving the Storm: Trauma and Recovery in Children’s Books about Natural Disasters • Pathways’ End: The Space of Trauma in Patrick Ness’s Chaos Walking • Hearing the Voices of “Comfort Women”: Confronting Historical Trauma in Korean Children’s Literature • Representations of Trauma and Recovery in Contemporary North American and Australian Teen Fiction • Resistant Rituals: Self-Mutilation and the Female Adolescent Body in Fairy Tales and Young Adult Fiction • Death Row Everyman: Stanislas Gros’s Image-Based Interpretation of Victor Hugo’s The Last Day of a Condemned Man Would you like to write for IBBY’s journal? Academic Articles ca. 4000 words The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Bookbird publishes articles on children’s literature with an international perspective four times a year Copyright © 2012 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the (in January, April, July and October). Articles that compare literatures of different countries are of interest, editors. as are papers on translation studies and articles that discuss the reception of work from one country in Editors: Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta—Augustana Faculty (Canada) and Lydia Kokkola, University of Turku another. Articles concerned with a particular national literature or a particular book or writer may also be (Finland) suitable, but it is important that the article should be of interest to an international audience. Some issues are devoted to special topics. Details and deadlines of these issues are available from Bookbird’s web pages. Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Augustana Faculty at the University of Alberta, Camrose, Alberta, Canada. -

T.Me/Booksandyou

The Mighty Wurlitzer The Mighty Wurlitzer HOW THE CIA PLAYED AMERICA Hugh Wilford HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2008 by Hugh Wilford All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilford, Hugh, 1965– The mighty wurlitzer : how the CIA played America / Hugh Wilford. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-674-03256-9 (pbk.) 1. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 2. Intelligence service—United States. 3. Cold War. 4. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 5. Public-private sector cooperation—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government—1945–1989. I. Title. JK468.I6W45 2008 327.1273009Ј045—dc22 2007021587 For Patty Contents List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Innocents’ Clubs: The Origins of the CIA Front 11 2 Secret Army: Émigrés 29 3 AFL-CIA: Labor 51 4 A Deep Sickness in New York: Intellectuals 70 5 The Cultural Cold War: Writers, Artists, Musicians, Filmmakers 99 6 The CIA on Campus: Students 123 7 The Truth Shall Make You Free: Women 149 8 Saving the World: Catholics 167 9 Into Africa: African Americans 197 10 Things Fall Apart: Journalists 225 Conclusion 249 Notes 257 Acknowledgments 319 Index 321 Illustrations Illustrations follow page 148. Allen Dulles Frank Wisner, 1934 A propaganda balloon release by the National Committee for a Free Europe George Meany and Jay Lovestone Sidney Hook, 1960 Arthur Koestler, Irving Brown, and James Burnham, 1950 Still from film adaptation of Orwell’s Animal Farm Henry Kissinger, 1957 U.S. -

The Unmaking of an American

Volume 17 | Issue 4 | Number 5 | Article ID 5253 | Feb 15, 2019 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Unmaking of an American Roger Pulvers On 15 March, Balestier Press brings out Roger “The Unmaking of an American” is a cross- Pulvers’ autobiography, “The Unmaking of an cultural memoir spanning decades of dramatic American.” history on four continents. The excerpts from the book below present a wide-ranging This book is an exploration of the nature of introduction to the range of Japanese memory and how it links us with people from contemporary cosmopolitan culture and moral different places and distant times. It ranges issues confronting Japan and the United States from Roger’s upbringing in a Jewish household at war from the Asia-Pacific War to the Vietnam in Los Angeles to his first trip abroad, in 1964, War, from war crimes tribunals of Japanese to the Soviet Union; from his days at Harvard generals to the firebombing and atomic Graduate School studying Russian to his stay in bombing of Japan, to the Vietnam War. They Warsaw, a stay that was truncated by a spy include introducing the author’s interactions scandal that rocked the United States; from his with leading Japanese filmmakers, playwrights arrival in Kyoto in 1967 to his years in and authors, among others: Oshima Nagisa Australia, where, in 1976, he gave up his (Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) and Shinoda American citizenship for an Australian one. Masahiro (Spy Sorge on Comintern espionage in China), playwright Kinoshita Junji (author of a play on the Sorge affair), and Koizumi Takashi (Best Wishes for Tomorrow). -

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press General Interest 1 Help the University of Nebraska Press continue its New in Paperback/Trade 46 vibrant program of publishing scholarly and regional Scholarly Books 64 books by becoming a Friend of the Press. Distribution 95 To join, visit nebraskapress.unl.edu or contact New in Paperback/Scholarly 96 Erika Kuebler Rippeteau, grants and development Selected Backlist 100 specialist, at 402-472-1660 or [email protected]. Journals 102 To find out how you can help support a particular Index 103 book or series, contact Donna Shear, Press director, at Ordering Information 104 402-472-2861 or [email protected]. Ebooks available for each title unless otherwise indicated. Subject Guide Africa 14, 30–32, 66, 78 History/American 2, 9, 13, 17–18, 20, Native American & Indigenous Studies 34–38, 48–50, 55–58, 63, 65, 68, 70, 15, 39, 52–55, 71, 80, 82–84, 86–87, African American Studies 14, 16, 50, 80–81, 84–87, 96–99 95–98 78, 99 History/American West 11–12, 25, 38, Natural History 37, 54 American Studies 73–75 54, 57, 59, 73, 95 Philosophy 40, 88 Anthropology 79, 83, 85–87 History/World 7, 18, 61, 68–70, 88, Poetry 14, 29–33, 41, 54, 56 Art & Photograph 7, 83 92–94 Political Science 4, 8, 11, 13, 24, 66, 85, Jewish History & Culture 35, 40–44 Asia 6–7, 17, 47 99 Bible Studies 43–44 Journalism 8, 20, 57, 65 Religion 39–41, 43–44, 88, 94 Biography 1, 8–9, 18, 23, 25, 36, 47, 56, Law/Legal Studies 4, 57, 70 Spain 90, 92–94 59, 62 Literature & Criticism 10, 32, 41, 44, Sports 1–3, 16–19, 34–35, 46–51, 65 -

The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America

The Mighty Wurlitzer The Mighty Wurlitzer HOW THE CIA PLAYED AMERICA Hugh Wilford HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2008 by Hugh Wilford All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilford, Hugh, 1965– The mighty wurlitzer : how the CIA played America / Hugh Wilford. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-674-03256-9 (pbk.) 1. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 2. Intelligence service—United States. 3. Cold War. 4. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 5. Public-private sector cooperation—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government—1945–1989. I. Title. JK468.I6W45 2008 327.1273009Ј045—dc22 2007021587 For Patty Contents List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Innocents’ Clubs: The Origins of the CIA Front 11 2 Secret Army: Émigrés 29 3 AFL-CIA: Labor 51 4 A Deep Sickness in New York: Intellectuals 70 5 The Cultural Cold War: Writers, Artists, Musicians, Filmmakers 99 6 The CIA on Campus: Students 123 7 The Truth Shall Make You Free: Women 149 8 Saving the World: Catholics 167 9 Into Africa: African Americans 197 10 Things Fall Apart: Journalists 225 Conclusion 249 Notes 257 Acknowledgments 319 Index 321 Illustrations Illustrations follow page 148. Allen Dulles Frank Wisner, 1934 A propaganda balloon release by the National Committee for a Free Europe George Meany and Jay Lovestone Sidney Hook, 1960 Arthur Koestler, Irving Brown, and James Burnham, 1950 Still from film adaptation of Orwell’s Animal Farm Henry Kissinger, 1957 U.S. -

By Priscilla

United States’ Track II Diplomacy During the Second North Korean Nuclear Crisis (2002-2008) by Priscilla Kim A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire February 2019 STUDENT DECLARATION FORM Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Collaboration Where a candidate’s research programme is part of a collaborative project, the thesis must indicate in addition clearly the candidate’s individual contribution and the extent of the collaboration. Please state below: This research programme was not part of a collaborative project Signature of Candidate ____ ___________________________ Type of Award ____ Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ School ____School of Languages and Global Studies______________ Abstract In the realm of academia and US government, scholars and policymakers argue that diplomacy is no longer a viable option towards dismantling North Korea’s nuclear program. I, however, argue that it is too early to declare diplomacy as a failed solution, due to the lack of research on Track II diplomacy between the US and North Korea. While there is a large amount of literature on US foreign policy towards North Korea, there is little literature that seeks to explain United States Track II diplomacy towards North Korea. -

Sugihara Chiune and the Japanese Conscience: Lest We Forget

Volume 3 | Issue 8 | Article ID 1584 | Aug 03, 2005 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Sugihara Chiune and the Japanese Conscience: Lest we forget Roger Pulvers Sugihara Chiune and the Japanesebe presented with a striking dilemma. Conscience: Lest we forget "My father woke up one morning in late July, By Roger Pulvers 1940, to see a great crowd of people milling outside the gate of the consulate," Hiroki told me in July 2000. "I remember staring down at them from the second-story window. They were Jews, and they had come to get exit visas from my father." Sixty years ago, during the evening of Aug. 14, 1945, Emperor Hirohito recorded the speech of Strict instructions surrender to be broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day at noon. Sugihara was under strict instructions from his superiors at the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo not Aug. 15, 1945 found Sugihara Chiune, his wife, to issue any Japanese visa other than a transit Yukiko, and their three little children in visa, and this only when the applicant had a Romania, interned there by the Red Army. It valid visa to a subsequent destination. was unclear what their fate would be. Japan Regarding this issue, as to the extent of had been officially at war with the Soviet Sugihara's insubordination, it has been said Union, albeit for only a few days. that the Foreign Ministry specifically forbade Sugihara, personally, from issuing visas. Who was Sugihara Chiune, and how did he Whatever the case (the point remains come to be in Bucharest at the war's end? At a disputed), Sugihara was certainly acting time when Japan is being branded in some contrary to procedures. -

Old Enemies, New Friends: Australia and the Impact of the Pacific War

Old Enemies, New Friends: Australia and the Impact of the Pacific War Peter Dennis The Second World War, and especially the Pacific War, was a profoundly disturbing experience for Australia. While for the metropolitan imperial centre, the United Kingdom, a ‘Germany first’ strategy against the three Axis powers made eminent sense, as indeed it did for its partners from mid to late 1941, the Soviet Union and the United States, for an outlying country such as Australia, the war posed fundamental questions about its priorities and interests. Well before the fall of Singapore exposed the hollowness of the overarching imperial defence policy centred on the naval base at Singapore, Australia had been increasingly concerned about the threat from Asia, and specifically the threat from Japan. Fear of Asia generally, and, from the mid to late nineteenth century, of Japan specifically, had been a constant thread in Australian considerations of its security and place in the region. Even before the Japanese naval victory over Russia at Tsushima in 1905, Australia fears that its interests were of a lesser order in the minds of imperial policy makers were confirmed by the conclusion of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. While this was regarded in British circles as a clever and timely answer to the emergence of Germany as the main threat to the United Kingdom, Australian leaders saw the withdrawal of British naval forces from the Pacific and the acknowledgment of Japan’s primacy in the region as an alarming development. Both the United Kingdom and Japan could point to tangible benefits that flowed from the alliance; Australia could see only a deterioration of its security position and, in the background, a questioning of its relationship with the ‘Mother Country.’1 How could Australian security be assured? One answer, an answer that continues to have resonance in the Australia of the 21st century, was to rely on ‘great and powerful friends’ to come to Australia’s aid in times of crisis. -

The Living Daylights 1(8) 4 December 1973

University of Wollongong Research Online The Living Daylights Historical & Cultural Collections 12-4-1973 The Living Daylights 1(8) 4 December 1973 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1973), The Living Daylights 1(8) 4 December 1973, Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.1 no.8, December 4 - 11, 28p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/8 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Living Daylights 1(8) 4 December 1973 Publisher Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.1 no.8, December 4 - 11, 28p This serial is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/8 W E A C C U S E H. HURLEY, general manager Phi - And their admen: F.E. GRACE lip Morris (Aust.) Ltd. (Brands: of Leo Burnett Pty Ltd; M.M. Marlboro, Alpine, Viscount, Al WALKER of Foote Cone & Belding bany, Philip Morris, Virginia Slims, Pty Ltd; R. HERTZ of Hertz Park Drive, Peter Jackson . .) Walpole Advertising Pty Ltd; H. And his admen: C.E. RICHARD PATON and A. ADAMSON of Noel SON, G.M. PATON and P.C. Paton Pty Ltd. BENNETT of U.S.P. Needham H. WIDDUP and J. RICKARDS Melbourne Pty Ltd; B.G. GAPES o f W.D.&H.O. Wills (Aust.) Ltd. and B. HARRIS of Compton (Brands: Ardath, Ascot, Benson& Advertising Aust. Pty Ltd; IL Hedges, Capstan, Claridge, Country HERBERT of Walker Herbert and Life, Craven A, Escort, Fiesta, Associates Pty Ltd; P& J.L. -

Acclaimed Japanese Books in Translation 2020

Acclaimed Japanese books in translation 2020 https://japanlibrary.jpic.or.jp Email:[email protected] Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC) 2-2-30 Kanda-Jinbocho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0051, Japan 一般財団法人 出版文化産業振興財団 〒 101-0051 東京都千代田区神田神保町2-2-30 共同ビル神保町4F BACKLIST 53 To make the wealth and breadth of Japanese tradition and thinking more accessible worldwide. Over 80,000 books are published every year in Japan, offering a diverse selection of information and ideas. In this great ocean of books, there are many works that can be enjoyed by a global audience, with troves of timeless knowledge amassed across the ages that both transcend history and cross borders. However, many such books remain largely unknown due to the language barrier and therefore limited number of translations. JAPAN LIBRARY is a collection of specially selected Japanese works in English, providing a broad range of titles from the vast canon of nonfiction—politics, foreign policy, social sciences, culture, philosophy, science and technology, and more. We strive to provide the deft translations and worldwide distribution needed to make the best of these works more accessible to a wider audience. We believe these works provide a useful start in fostering mutual discussion and understanding, ultimately contributing towards the enrichment of a universal, global knowledge. 54 BACKLIST NEW TITLES Political Science History, Memory, and Politics in Postwar Japan Edited by IOKIBE Kaoru, KOMIYA Kazuo, HOSOYA Yuichi, MIYAGI Taizo, and the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research’s Political and Diplomatic Review Project Translated by Christopher F. Ryal emories can be shared―or contested. Japan and Korea, just one case in point, share centuries of intertwined history, the nature of which continues toM be disputed, particularly with regard to World War II. -

Performing Father–Daughter Love: Inoue Hisashi's Face of Jizo

9/3/2015 Intersections: Performing FatherDaughter Love: Inoue Hisashi's <i>Face of Jizo</i> Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific Issue 16, March 2008 Performing Father–Daughter Love: Inoue Hisashi's Face of Jizo Tomoko Aoyama 1. It is generally agreed that the father–daughter relationship has suffered from a lack of attention for centuries in many cultures around the globe.[1] In the nuclear family, according to Esperanza RamirezChristensen, it is 'at once the most superfluous and the most revealing'[2] of all relationships, including those between husband and wife, parent and child, and siblings. Ramirez Christensen continues: It is superfluous because the daughter's traditional structural role in the middleclass family has been negligible. She was not expected to carry on the father's name and patrimony, which belonged to the son. At best, she was her mother's helper, a temporary family member until marriage took her away to assume her proper structural role as wife and mother in another family. And yet it is just this ambiguity of the daughter's positioning as both insider and outsider that brings into focus the nature of the family as an artificial social construction constituted by the patriarchal imperative to perpetuate itself. Through marriage with another family's son, the daughter has been the necessary link in the formation of the social alliances that structure the community.[3] Despite this relative neglect and the 'virtual absence of critical studies,'[4] there are a number of conspicuous representations of father–daughter relations in mythology, drama, literature, and film.