Environmental Factors in the Development of Parkinson's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Fifteenth Scientific Symposium

FLIGHT ATTENDANT MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2002-2017 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2017 ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Publications 2017 ............................................................................................................................ 5 Presentations and Abstracts 2017 ........................................................................................ 13 Book Chapters, etc., 2017 .......................................................................................................... 16 2016 .............................................................................................................................................................. 17 Publications 2016 ......................................................................................................................... 17 Presentations and Abstracts 2016 ........................................................................................ 32 Book Chapters, etc., 2016 .......................................................................................................... 38 2015 ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Serving the State: Wisconsin Legislators, 1848–2021

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU Serving the State: Wisconsin Legislators, 1848–2021 WISCONSIN HISTORY PROJECT • February 2021, Volume 3, Number 7 © 2021 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Wisconsin Senate, 1848–2021 Name Party District Sessions served in the senate A Abert, George A.* D 7 1877, 1878 Abrams, William J.* D 2 1868, 1869 Ackley, Edward F. R 28 1913, 1915 Ackley, Henry M. D 10 1882, 1883 Adams, Henry* U/R 24 1866, 1867, 1868, 1869 Adams, John* D 26 1882, 1883 Adams, John Q.* D/R 25 1854, 1855, 1856 Adelman, Lynn S. D 28 1977, 1979, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1995, 1997 Agard, Melissa* D 16 2021 Alban, James S. W 2 1852, 1853 Albers, W. W. D 25 1911, 1913, 1915, 1917 Allen, Benjamin D 19 1853, 1854 Altpeter, Oscar D 6 1893, 1895 Anderson, Al C. R 29 1917, 1919, 1921 Anderson, John A. R/P 29 1931, 1933, 1935, 1937 Anderson, Matthew* D 26 1878, 1879, 1880, 1881 Andrea, Joseph F.* D 22 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1995 Andrews, Abraham D. R 30 1878, 79 Anson, Frank A.* R 5 1899, 1901 Apple, Adam* D 3 1891, 1893 Arnold, Alexander A.* R 29 1877, 1878 Arnold, Louis A. -

Oncolytic Virus-Induced Autophagy in Glioblastoma

cancers Review Oncolytic Virus-Induced Autophagy in Glioblastoma Margarita Kamynina 1, Salome Tskhovrebova 1, Jawad Fares 2 , Peter Timashev 3,4,5 , Anastasia Laevskaya 1 and Ilya Ulasov 1,* 1 Group of Experimental Biotherapy and Diagnostic, Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119991 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (A.L.) 2 Department of Neurological Surgery, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA; [email protected] 3 Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119991 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 4 Department of Polymers and Composites, N. N. Semenov Institute of Chemical Physics, 119991 Moscow, Russia 5 Chemistry Department, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991 Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive brain tumor with an incidence rate of nearly 3.19/100,000. Current therapeutic options fall short in improving the survival of patients with GBM. Various genetic and microenvironmental factors contribute to GBM progression and resistance to therapy. The development of gene therapies using self-replicating oncolytic viruses can advance GBM treatment. Due to GBM heterogeneity, oncolytic viruses have been genetically modified to improve the antiglioma effect in vitro and in vivo. Oncolytic viruses can activate autophagy signaling in GBM upon tumoral infection. Autophagy can be cytoprotective, Citation: Kamynina, M.; whereby the GBM cells catabolize damaged organelles to accommodate to virus-induced stress, or Tskhovrebova, S.; Fares, J.; Timashev, cytotoxic, whereby it leads to the destruction of GBM cells. -

Wisconsin Legislative Directory

WISCONSINWISCONSIN LEGISLATIVE DIRECTORY LEGISLATIVE 2013 – 2014 SESSION State Legislative Hotline DIRECTORY (800) 362-9472 Madison Area Legislative Hotline 2013 -2014 SESSION (608) 266-9960 State TDD Legislative Hotline (800) 228-2115 Wisconsin Legislature Website www.legis.wisconsin.gov State of Wisconsin Website www.wisconsin.gov WISCONSIN FEDERAL DELEGATION – UNITED STATES SENATORS Tammy Baldwin (D) Ron Johnson (R) 717 Hart Senate Office Building 328 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 (202) 224-5653 (202) 224-5323 WISCONSIN CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS Office Name (Party) Phone (608) Governor Scott Walker (R) 266-1212 Lt. Governor Rebecca Kleefisch (R) 266-3516 Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen (R) 266-1221 Secretary of State Douglas LaFollette (D) 266-8888 Treasurer Kurt Schuller (R) 266-1714 Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Evers 266-1771 UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 Rep. (Party) District Office Phone (202) Duffy, Sean (R) 7 1208 Longworth 225-3365 Kind, Ron (D) 3 1502 Longworth 225-5506 Moore, Gwen (D) 4 2245 Rayburn 225-4572 Petri, Thomas (R) 6 2462 Rayburn 225-2476 Pocan, Mark (D) 2 313 Cannon 225-2906 Ribble, Reid (R) 8 1513 Longworth 225-5665 Ryan, Paul (R) 1 1233 Longworth 225-3031 Sensenbrenner, James (R) 5 2449 Rayburn 225-5101 WISCONSIN ASSEMBLY – OFFICERS Rep. (Party) Name (Party) Capitol Room Phone (608) Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R) 211-W 266-3387 Speaker Pro Tempore Bill Kramer (R) 103-W 266-8580 Majority Leader Scott Suder (R) 115-W 266-2401 Assistant Majority Leader Jim Steineke (R) 204-N 266-2418 Minority Leader Peter Barca (D) 201-W 266-5504 Assistant Minority Leader Sandy Pasch (D) 119-N 266-7671 Chief Clerk Patrick E. -

Change of Name 1970'S.Xlsx

Original Surname Original Given Name Address New Surname New Given Name Application Date Publication Date Abdulsalam Amal Yacoub Saskatoon Abdul Salam Amy Jacob M. May 12, 1978 May 26, 1978 Abdulsalam Amani Yacoub Saskatoon Abdul Salam Amani Jacob May 12, 1978 May 26, 1978 Abdulsalam Dina Yacoub Saskatoon Abdul Salam Dina Jacob May 12, 1978 May 26, 1978 Abdulsalam Mazin Yacoub Saskatoon Abdul Salam Mazin Jacob May 12, 1978 May 26, 1978 Abdulsalam Yacoub Mohammad Saskatoon Abdul Salam Jacob M. May 12, 1978 May 26, 1978 Abel Colleen Dora Regina Peterson Colleen Dora June 27, 1978 July 21, 1978 Achaynum Robert John Gallivan Strike-Him-On-The-Back Robert John October 28, 1977 November 10, 1977 Achs Lane Taylor Saskatoon Atkinson Lane Taylor March 21, 1974 April 5, 1974 Adair Cynthia Arlene Estevan Rutledge Cynthia Arlene May 31, 1973 June 8, 1973 Adair Evelyn Alexandria Margarette Estevan Rutledge Evelyn Alexandria Margarette May 31, 1973 June 8, 1973 Adair William Allister Cameron Estevan Rutledge William Allister Cameron May 31, 1973 June 8, 1973 Adams Albert Wynne Regina McBeath Albert Wynne April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adams Edward Wayne Regina McBeath Edward Wayne April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adams Gail Fern Regina McBeath Gail Fern April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adams Patricia Louise Regina McBeath Patricia Louise April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adams Robert Gordon Regina McBeath Robert Gordon April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adams William Arthur Brad Regina McBeath William Arthur Brad April 1, 1977 April 15, 1977 Adrian David Prince Albert Walker -

Parkinson's Disease and Peripheral Neuropathy

Chapter 4 Parkinson’s Disease and Peripheral Neuropathy Peter Podgorny and Cory Toth Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/57106 1. Introduction Idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD), an age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder without known cause, is well known to manifest with rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and gait instability on examination [1, 2]. However, other ancillary manifestations have become accepted over the years, including cognitive decline, depression, and autonomic dysfunction [3]. All of these clinically presenting features have long been known to result from disease within the central nervous system, where IPD is pathologically associated with degeneration of the substantia nigra [4]. The possibility of peripheral nervous system functional or pathological involvement in IPD has only recently been considered. One form of peripheral nervous system disease is a peripheral neuropathy, a distal-predominant process affecting the feet and legs, and in more severe cases, the hands and torso [5]. Peripheral neuropathy can manifest as a disease of the axons or the myelin, or both, within nerve fibers. In addition, sensory nerve fibers carrying information for touch, pain and temperature sensations (small nerve fibers termed Aδ and C fibers) as well as for vibration detection and proprioception (large nerve fibers termed Aα and Aβ fibers) can be selectively affected. In most cases, sensory dysfunction appears first, followed by further disease of large nerve fibers leading to loss of reflexes and the possible development of weakness. Symptoms of a peripheral neuropathy may include the early onset of numbness, tingling or prickling sensations, followed by the later onset of incoordination, weakness and pain [6]. -

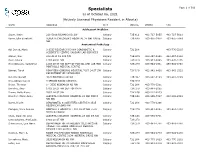

Specialists Page 1 of 509 As of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta)

Specialists Page 1 of 509 as of October 06, 2021 (Actively Licensed Physicians Resident in Alberta) NAME ADDRESS CITY POSTAL PHONE FAX Adolescent Medicine Soper, Katie 220-5010 RICHARD RD SW Calgary T3E 6L1 403-727-5055 403-727-5011 Vyver, Ellie Elizabeth ALBERTA CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-2978 403-955-7649 NW Anatomical Pathology Abi Daoud, Marie 9-3535 RESEARCH RD NW DIAGNOSTIC & Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3295 SCIENTIFIC CENTRE CALGARY LAB SERVICES Alanen, Ken 242-4411 16 AVE NW Calgary T3B 0M3 403-457-1900 403-457-1904 Auer, Iwona 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-8225 403-270-4135 Benediktsson, Hallgrimur 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATHOL AND LAB MED Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-1981 493-944-4748 FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE Bismar, Tarek ROKYVIEW GENERAL HOSPITAL 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-943-8430 403-943-3333 DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY Bol, Eric Gerald 4070 BOWNESS RD NW Calgary T3B 3R7 403-297-8123 403-297-3429 Box, Adrian Harold 3 SPRING RIDGE ESTATES Calgary T3Z 3M8 Brenn, Thomas 9 - 3535 RESEARCH RD NW Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3201 Bromley, Amy 1403 29 ST NW DEPT OF PATH Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-5055 Brown, Holly Alexis 7007 14 ST SW Calgary T2V 1P9 403-212-8223 Brundler, Marie-Anne ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DRIVE Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7387 403-955-2321 NW NW Bures, Nicole DIAGNOSTIC & SCIENTIFIC CENTRE 9 3535 Calgary T2L 2K8 403-770-3206 RESEARCH ROAD NW Caragea, Mara Andrea FOOTHILLS HOSPITAL 1403 29 ST NW 7576 Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-6685 403-944-4748 MCCAIG TOWER Chan, Elaine So Ling ALBERTA CHILDREN HOSPITAL 28 OKI DR NW Calgary T3B 6A8 403-955-7761 Cota Schwarz, Ana Lucia 1403 29 ST NW Calgary T2N 2T9 DiFrancesco, Lisa Marie DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY (CLS) MCCAIG Calgary T2N 2T9 403-944-4756 403-944-4748 TOWER 7TH FLOOR FOOTHILLS MEDICAL CENTRE 1403 29TH ST NW Duggan, Maire A. -

2017 Delinquent Publication

############ Delinquent Advertising List DelqAdvertisingList.rpt 2:53 PM Cuyahoga Page -1 of 1 2018 Pay 2019 Delinquent Property number Owner Name Property Description Acres Valuations Amount 0010 - Bay Village 201-08-014 CANNATA, KENNETH A 98 BAYV 1/39TH INT IN BLOCK A 0005 AL 0.1804 67660 3,433.04 201-08-049 Gomola Robert J 92 SP 585.62FT S OF CL W LAKE RD 0009 0.1756 46030 859.19 201-14-005 Waters, Stephen R 97 WILLGEMAR 0033 ALL 0.2617 66050 5,965.01 201-15-048 Vick, James 91 BAYENTPRS#2 0017 ALL 0.3444 85930 183.82 201-17-045 Quinn, John J 91 WP 490.09FT EP 0.3673 72450 169.60 201-17-046 THOMSON, THOMAS E. 91 NWC BEXLEY DR 0.3616 73750 278.09 201-18-040 POSZA EVA & KOHLER, SHARON91 NP 1222.56FT N OF CL WOLF RD 0.4050 60520 2,848.15 201-23-036 BORST, CHARLES A & BORST, LI 81 BAY-GARDENS EST#3 0001 ALL 0.4644 106050 186.44 201-25-017 RYAN THOMAS P & JENNIFER 81 CON-WELL #2 0121 0.3576 108890 232.94 201-26-035 HARTRANFT, PAUL W. & CATHLE81 BROOKE ESTATES SUB 0033 ALL 0.3508 80960 7,659.05 201-28-041 SIGNATURE BUILDING CONCEPT98 NP 1042.45FT SWC 80 FT IN REAR 0.4192 63040 6,383.16 201-35-007 Shiry Dora R 92 DIETRICH DELUXE HOMES#1 0014 A 0.2796 109830 219.07 201-37-033 WATERS, ROBERT J 92 NP 205N OF WEST- LAWN DR 0.3719 72700 7,184.87 202-03-035 Escovar Barbara A TRUSTEE 93 THOMAS TERRY 0001 ALL 0.3551 132340 746.79 202-04-055 O'Connell, Christopher M. -

Emerging Applications of Nanotechnology in Healthcare Systems: Grand Challenges and Perspectives

pharmaceuticals Review Emerging Applications of Nanotechnology in Healthcare Systems: Grand Challenges and Perspectives Sumaira Anjum 1,* , Sara Ishaque 1,†, Hijab Fatima 1,†, Wajiha Farooq 1,†, Christophe Hano 2 , Bilal Haider Abbasi 3 and Iram Anjum 1 1 Department of Biotechnology, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore 54000, Pakistan; [email protected] (S.I.); [email protected] (H.F.); [email protected] (W.F.); [email protected] (I.A.) 2 Laboratoire de Biologie des Ligneux et des Grandes Cultures (LBLGC), INRAe USC1328, Université d’Orléans, 28000 Chartres, France; [email protected] 3 Department of Biotechnology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad 54000, Pakistan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +92-300-6957038 † All these authors have equal contribution. Abstract: Healthcare, as a basic human right, has often become the focus of the development of innovative technologies. Technological progress has significantly contributed to the provision of high-quality, on-time, acceptable, and affordable healthcare. Advancements in nanoscience have led to the emergence of a new generation of nanostructures. Each of them has a unique set of properties that account for their astonishing applications. Since its inception, nanotechnology has continuously affected healthcare and has exerted a tremendous influence on its transformation, contributing to better outcomes. In the last two decades, the world has seen nanotechnology taking steps towards its omnipresence and the process has been accelerated by extensive research in various healthcare sectors. Citation: Anjum, S.; Ishaque, S.; The inclusion of nanotechnology and its allied nanocarriers/nanosystems in medicine is known as Fatima, H.; Farooq, W.; Hano, C.; nanomedicine, a field that has brought about numerous benefits in disease prevention, diagnosis, and Abbasi, B.H.; Anjum, I. -

July 1, 1987 to June 30, 1988 I STOUT UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION

July 1, 1987 to June 30, 1988 I STOUT UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION How WE CAME To BE "This feeling that the Founda tion president, assumed the mantle tion is here to help with both of leadership from Milavitz four leadership and funds is filtering years ago. In addition to the through the faculty and student volunteer work of many in body. They are using the Founda dividuals, the Foundation has had don's office more frequently as a just four individuals as its ex- source of assistance. To me, this ecutive director. Dr. John Furlong means that the Foundation is view was originally hired by President ed as a viable organization that has Micheels to come to Stout, with an esse,ntial role to play on this one of his assignments being the campus as a partner of the univer leadership of the Stout Founda sity. " -- President William J. tion. Dr. Furlong ably led the Micheels, 1970. Foundation in its early years, then These words from President hired Lloyd'Trent to serve as its William J. Micheels introduced the executive director from 1964-1968. 1970 Annual Report of the Stout At Lloyd's death, Jack Wile was Foundation. Founded just seven hired and served until1980. He years earlier by President Micheels. was succeeded by the current ex who had newly ,assumed his post as ecutive director, Dave Williams. president of Stout State University, The constancy of the leadership of the Foundation was well on its way the Foundation has been one con to becoming a force in the life of tributing factor to the steady the university. -

Chancellor's Welcome

CHANCELLOR'S WELCOME On behalf of Simon Fraser University, it is my honour to welcome you to our June 2011 Convocation Ceremony. Simon Fraser University is proudly different. In fact, an important part of the vision for this University has always been about being different in ways that mattered, ways that would benefit our students, our faculty and the conmmnities we serve. Since we first opened on September 9th, 1965 with 2, 500 students, Simon Fraser University has been building the traditions and reputation that define us. Our university has stayed true to the core philosophy and values upon which it was built. We are proud of our reputation for intellectual and academic freedom and our unfaltering commitment to academic innovation and lifelong learning. It is our willingness to be different that sets us apart as innovators and mavericks. Through innovative teaching, research and conununity outreach, we continue to foster discovery, diversity and dialogue. Convocation celebrates an important milestone for our students, their families, teachers and friends. In selecting Simon Fraser University, our students chose an education that inspires open-minded, adaptable and resilient lifelong learning. We honour our students for their achievements and commitment and wish them every success in realizing their unique individual potential within their chosen communities, professions and industries. Brandt C. Louie Chancellor PRESIDENT'S WELCOME Convocation marks an important milestone in your life. I join vvith others in offering you my warm congratulations on this extraordinary achievement. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to members of your family and all others who made it possible for you to pursue your studies at Simon Fraser University. -

Technical Brief No. 39: Disparities and Barriers to Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Care

Technical Brief Number 39 R Disparities and Barriers to Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Care Technical Brief Number 39 Disparities and Barriers to Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Care Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 75Q80120D00009 Prepared by: Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center Los Angeles, CA Investigators: Erin M. Mobley, Ph.D. Diana J. Moke, M.D. Joel Milam, Ph.D. Carol Y. Ochoa, M.P.H. Julia Stal, B.A. Nosa Osazuwa, B.A. Maria Bolshakova, B.S. Jai Kemp, B.A. Jennifer E. Dinalo, Ph.D. Aneesa Motala, B.A. Drizelle Baluyot, B.A. Susanne Hempel, Ph.D. AHRQ Publication No. 21-EHC014 March 2021 Key Messages Purpose of Review This Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Technical Brief was commissioned by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to support the development of a research agenda associated with the Childhood Cancer Survivorship, Treatment, Access, and Research (STAR) Act. This Technical Brief provides an overview of the existing evidence and forthcoming research relevant to disparities and barriers for pediatric cancer survivorship care, outlines open questions, and offers concrete guidance for future research in a user-friendly format. Key Messages • In total, 110 studies were identified that addressed disparities, barriers to survivorship care, proposed strategies, evaluated interventions, and ongoing studies in childhood cancer survivors. • Twenty-six studies assessed disparities in survivorship care. The most commonly examined sources of disparities impacting survivorship care were biological sex and insurance. • Forty-seven studies assessed barriers to survivorship care at various levels and their impact on key outcome domains.