An Interview with Bobby Morris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Cover the Risk So You Can Focus on the Reward

CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 1 WE COVER THE RISK SO YOU CAN FOCUS ON THE REWARD. You’ve worked hard for your assets. Protect them against misfortune. KUDA COVERS YOUR RACEHORSE: Mortality Cover, Lifesaving Surgery and Critical Care Cover, Medical Care Cover, and Public Liability Cover. KUDA COVERS EVERYTHING ELSE: We cover all your valued assets: Personal and Commercial Insurance, Sport Horse Insurance, and Game and Wildlife Insurance. If you trust us with covering your valued thoroughbred, you can trust us to cover all your assets. CALL US TODAY FOR COVER FROM THE LUXURY LIFESTYLE INSURANCE SPECIALISTS. WÉHANN SMITH +27 82 337 4555 JO CAMPHER +27 82 334 4940 ninety9cents 42088T ninety9cents Kuda Holdings - Authorised Financial Services Provider, FSP number: 38382. All policies are on a Co-Insurance basis between Infiniti Insurance and various syndicates of Lloyds. Kuda Holdings approved Lloyds coverholder PIN 112897CJS. 2 CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 42088T Kuda Turf Directory Print Ad Luxury lifestyle insurance 210 x 148 FA2.indd 1 2018/12/19 2:48 PM CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 3 VENDOR INDEX Lot Colour Sex Breeding On Account of Cheveley Stud. (As Agent) 43 Chestnut Mare Oxbow Lake by Fort Wood (USA) 45 Chestnut Mare Tippuana by Fort Wood (USA) 51 Chestnut Mare Silent Treatment by Jet Master 56 Chestnut Mare Rachel Leigh by Fort Wood (USA) 70 Bay Mare Miss K by Kahal (GB) 72 Chestnut Mare Giant's Slipper (AUS) by Giant's Causeway (USA) 76 Grey Mare Ado Annie by Trippi (USA) 84 Bay Mare Lavender Bells by Al Mufti (USA) On Account of Harold Crawford Racing. -

WWE Legend Mr. Fuji Passes Away

WWE legend Mr. Fuji passes away Author : Robert D. Cobb The WWE universe lost a legend today. As reported through WWE.com, Former WWE Hall of Famer Mr. Fuji passed away at the age of 82. As of now, there is no cause for his passing. Mr. Fuji was involved in professional wrestling from 1965 until 1985 as a wrestler and then transformed into a heel manager from 1985 to 1996. He made his professional wrestling debut on December 15, 1965, in his native Hawaii. When he made his debut, though, he was under his ring name Mr. Fujiwara.It would be less than a month into his wrestling career that he would win his first belt, and that would be the NWA Hawaii Tag Team with Curtis Iaukea on January 7, 1966. It would be at that point where he would shorten his name to Mr. Fuji and would start touring many territories. Territories were a feature in wrestling before Vince McMahon bought the WWF into the 21st century and started buying up many of the territories. Mr. Fuji would continue to tour the territories util 1972. In 1972, he would make his debut for WWWF as a heel. He would form a tag team with Professor Tanaka and would be managed by one of the legendary heel managers, the Grand Wizard. During his run with Tanaka is where Mr. Fuji would begin throwing salt into his opponent's faces. He would win his first title in WWWF on June 27, 1972, when they would defeat Sonny King and Chief Jay Strongbow for the World Tag titles. -

Welcome New Glass Officers!

{ MARIAN LIBRARY-DAEMEN COLLEGE The Campus-wide Connection for News Volume 47 Number 2 October 1991 Welcome New Glass Officers! The Student Association of Programming; Michael Robinson, Carpenter also says that greek groups Student Activities Fee funding. proudly announces the newly elected Vice President of Publications; David want to see a great» diversity of greek At their weekly meetings presidents of each class. These new Breau, Treasurer, and Coreen Flynn, organizations represented in the budget requests are discussed, often officers are: Elizabeth Blanco, senior Secretary. Student Association. Phil Sciolino, debated, and finally voted on. A class; Peter Yates, junior class; Prior to the spring, it had been President of the Student Association, representative from the student Michael Malark, sophmore class; Eric many years since a complete ballot of says “we’re making students more organization submitting the request is Bender, freshmen class. ' officers existed, and then those aware that we're here. We're pushing required to be present to answer any Once again, the Student positions most frequently ran unop student involvement”. questions of die Student Association. Association had a successful election posed. The Ascent asked a few "So what does the Student Bubget recommendations are with candidates running for each class students what they attribute to the approved, denied, or adjusted accord president's position. Not only were growing interest in the student Association really do?"______ ing to a majority consensus of the there candidates for each position, but government on campus. One of the important duties Senate (the Senate consists of the 6 there were also candidates running in Vice President of Governing of the Student Association is to vote on executive members and 4 class opposition for each position (except to the Student Association, Ellen recommendations for the use of the presidents). -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Monday January 22, 2018

Monday January 22, 2018 * Round Trip Motorcoach Transportation * $25.00 in Slot Play * Admission to the 3 PM “SOCK HOP” Show in The Theatre at Harrah’s Atlantic City * All Tax & Tips Except Driver $100.00 SLOT $100.00 Group Leader PLAY PRIZE FOR Cash Rebate with 1 LUCKY WINNER 40 or more paying $38.00 ON EACH BUS!!!! per person passengers! * Valid for a minimum of 40 paying passengers. The 41st and 42nd passengers Go Free! *Show catalogue subject to errors and/or omissions (Valid for departures from Philadelphia and the immediate surrounding suburbs) *If show must cancel due to inclement weather, an alternate show make-up date will be offered. Call Wally at 1-800-640-0701 JOEY VINCENT “Live at SugarHouse Casino” Monday, March 5, 2018 ......Fast paced humor, rapid fire costume change impressions and a musical tribute to the trumpet greats are Price based on a just part of the fun. From Harry James to James Brown, minimum of 40 $36 Stevie Wonder to Willie Nelson, Louis Armstrong to Luciano paying passengers. Pavarotti, Joey Vincent will take you on a musical journey The 41st & 42nd Per Person from the 30's up to the present! passengers go free! Package Includes: *All Bonuses are subject to casino + Round Trip Motorcoach Transportation rules & exclusions may apply. + $20.00 Slot Play Must be 21 years or older, + Admission to the 3:00 PM “JOEY VINCENT” *Valid for departures from Philadelphia and Show at SugarHouse Casino in Philadelphia the immediate surrounding suburbs + All Tax and Tips Except Driver T If show must cancel due to inclement weather, show will be rescheduled. -

Louis Prima Collection Donated to the Tulane Hogan Jazz Archive

Tulane University Louis Prima collection donated to the Tulane Hogan Jazz Archive September 24, 2015 2:30 AM Carolyn Scofield [email protected] 247-1443 He grew up playing music in New Orleans but Louis Prima"s talent as an artist and entertainer made him world-renowned. Now, artifacts belonging to the great jazz trumpeter, vocalist and composer, including films, recordings, diaries and sheet music, are coming home to the William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz at Tulane University. “Prima"s iconic status as an artist and entertainer whose career spanned half a century and included hits such as "Jump, Jive an" Wail" and "Just a Gigolo â⬓ I Ain"t Got Nobody," makes this one of the most notable donations ever received by the Hogan Jazz Archive,” said Bruce Raeburn, director of Special Collections and curator of the Hogan Jazz Archive. The collection was donated by the Gia Maione Prima Foundation, Inc, founded by Prima"s wife and lead vocalist. Tulane will dedicate a Louis Prima Room to house the collection in Jones Hall in 2017. Prima is one of New Orleans" most influential musicians, bringing the sounds of the city to audiences across the globe. His style evolved through the years, from Dixieland jazz to swing to pop, even rock and roll. His legacy continues today. Generations of children know Prima"s voice as King Louie in Disney"s The Jungle Book. The Brian Setzer Orchestra won a Grammy covering Prima"s 1956 song “Jump, Jive an" Wail.” “We are excited to partner with Tulane University and be able to fulfill his late wife Gia"s dream of bringing the Louis Prima Archives to his hometown of New Orleans. -

Stage Door Swings Brochure

. 0 A G 6 E C R 2 G , O 1 FEATURING A H . T T D C I O I S F A N O E O A P T B R I . P P G The Palladium Big 3 Orchestra S M . N N R U O E O Featuring the combined orchestras N P L of Tito Puente, Machito and Tito Rodriguez presents Manteca - The Afro-Cuban Music of The Dizzy Gillespie Big Band FROM with special guest Candido CUBAN FIRE Brazilliance featuring TO SKETCHES Bud Shank OF SPAIN The Music of Chico O’ Farrill Big Band Directed by Arturo O’Farrill Bill Holman Band- Echoes of Aranjuez 8 3 0 Armando Peraza 0 - 8 Stan Kenton’s Cuban Fire 0 8 0 Viva Tirado- 9 e The Gerald Wilson Orchestra t A u t C i Jose Rizo’s Jazz on , t s h the Latin Side All-Stars n c I a z Francisco Aguabella e z B a Justo Almario J g n s o Shorty Rogers Big Band- e l L , e Afro-Cuban Influence 8 g 3 n Viva Zapata-The Latin Side of 0 A 8 The Lighthouse All-Stars s x o o L Jack Costanzo B . e O h Sketches of Spain . P T The classic Gil Evans-Miles Davis October 9-12, 2008 collaboration featuring Bobby Shew Hyatt Regency Newport Beach Johnny Richards’ Rites of Diablo 1107 Jamboree Road www.lajazzinstitute.org Newport Beach, CA The Estrada Brothers- Tribute to Cal Tjader about the LOS PLATINUM VIP PACKAGE! ANGELES The VIP package includes priority seats in the DATES HOW TO amphitheater and ballroom (first come, first served JAZZ FESTIVAL | October 9-12, 2008 PURCHASE TICKETS basis) plus a Wednesday Night bonus concert. -

What We've Made of Louis Prima John J

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 1-1-2005 Taming the Wildest: What We've Made of Louis Prima John J. Pauly Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Taming the Wildest: What We've Made of Louis Prima," in Afterlife as Afterimage: Understanding Posthumous Fame. Eds. Steve Jones and Joli Jensen. New York: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2005: 191-208. Publisher Link. © 2005 Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. Used with permission. chapter 1 O Taming the Wildest What We've Made of Louis Prima jOHN j. PAULY For over forty years, Louis Prima had survived one change after another in the pop~ ular music business. He was, in succession, a trumpet section player in his home~ town ofNew Orleans, the front man for a popular New York City jazz quintet, and the leader of a touring big band. In the 1950s, with his career flagging, he reinvent~ ed himself as a spectacular Las Vegas lounge act, then nudged his career through the 1960s with help from his old friend, Walt Disney. He explored many forms of popular music along the way, but aspired only, in his own words, to "play pretty for the people." The same man who wrote the jazz classic "Sing, Sing, Sing," would also record easy listening instrumental music, Disney movie soundtracks, and ltalian~American novelty songs. In all these reincamations, he performed with an exuberance that inspired his Vegas nickname, "the wildest." Prima's career would end in deafening silence, however. He spent the last thirty~five months of his life in a coma, following a 197 5 operation in which doctors partially removed a benign tumor from his brain stem. -

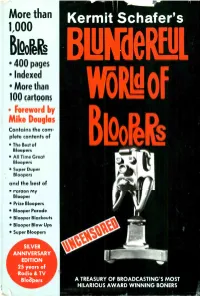

Blunderful-World-Of-Bloopers.Pdf

o More than Kermit Schafer's 1,000 BEQ01416. BLlfdel 400 pages Indexed More than 100 cartoons WÖLof Foreword by Mike Douglas Contains the com- plete contents of The Best of Boo Ittli Bloopers All Time Great Bloopers Super Duper Bloopers and the best of Pardon My Blooper Prize Bloopers Blooper Parade Blooper Blackouts Blooper Blow Ups Super Bloopers SILVER ANNIVERSARY EDITION 25 years of Radio & TV Bloópers A TREASURY OF BROADCASTING'S MOST HILARIOUS AWARD WINNING BONERS Kermit Schafer, the international authority on lip -slip- pers, is a veteran New York radio, TV, film and recording Producer Kermit producer. Several Schafer presents his Blooper record al- Bloopy Award, the sym- bums and books bol of human error in have been best- broadcasting. sellers. His other Blooper projects include "Blooperama," a night club and lecture show featuring audio and video tape and film; TV specials; a full - length "Pardon My Blooper" movie and "The Blooper Game" a TV quiz program. His forthcoming autobiography is entitled "I Never Make Misteaks." Another Schafer project is the establish- ment of a Blooper Hall of Fame. In between his many trips to England, where he has in- troduced his Blooper works, he lectures on college campuses. Also formed is the Blooper Snooper Club, where members who submit Bloopers be- come eligible for prizes. Fans who wish club information or would like to submit material can write to: Kermit Schafer Blooper Enterprises Inc. Box 43 -1925 South Miami, Florida 33143 (Left) Producer Kermit on My Blooper" movie opening. (Right) The million -seller gold Blooper record. -

Similar Hats on Similar Heads: Uniformity and Alienation at the Rat Pack’S Summit Conference of Cool

University of Huddersfield Repository Calvert, Dave Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool Original Citation Calvert, Dave (2015) Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool. Popular Music, 34 (1). pp. 1-21. ISSN 0261-1430 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/22182/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool Abstract This article considers the nightclub shows of the Rat Pack, focussing particularly on the Summit performances at the Sands Hotel, Las Vegas, in 1960. Featuring Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop, these shows encompassed musical, comic and dance routines, drawing on the experiences each member had in live vaudeville performance.